Pregnancy & Recovery

PREGNANCY

PREGNANCY

While specific substances can impact the reproductive cycles to increase the likelihood of infertility and early onset of menopause in women, the number of infants being born with substance dependence is on the rise.

Prenatal Substance Use

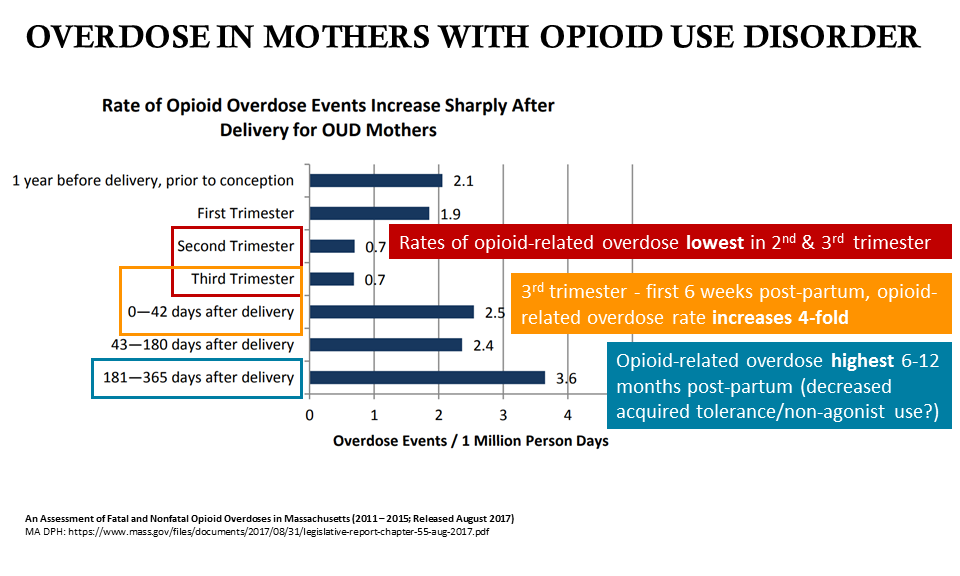

The prevalence of opioid use disorder during pregnancy has increased by 127%, from 1.7 per 1,000 delivery admissions in 1998, to 3.9 per 1,000 delivery admissions in 2011. Even more recently, almost 1% of pregnant women reported non-medical use of opioids in the past 30 days.

Prenatal use of alcohol or other drugs is dangerous to the mother, and can also cause permanent damage to the child. Prenatal use of illicit opioids and certain medication assisted treatments for opioid use disorders (e.g. methadone) has been linked to Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS), while prenatal use of alcohol use disorder has been linked to Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS). Both syndromes are assessed on a sliding scale of severity, and impair the growth, cognitive development, and health of the child to varying degrees (depending on the severity of the mother’s substance use disorder).

The threat of punishment for substance use during pregnancy is known to stop women from seeking prenatal care. In cases where mothers have received no prenatal care, the babies are 3x more likely to have a low birth rate, and 5x more likely to die in infancy. Treatment and prenatal care for women with substance use disorder can reduce the impact of substance use on the fetus to improve birth outcomes, increasing birth weight and rates of non-substance dependent infants. Prenatal care is also an opportunity for providers to help connect pregnant women with specialized treatment for addiction.

PREGNANCY-SPECIFIC SENSITIVITIES

- CO-OCCURRING

-

Pregnant women who have experienced sexual abuse have shown higher substance use disorder behaviors than their counterparts.

Postpartum depression (see: After Birth- Postpartum)

- EMOTIONAL FACTORS

-

Pregnancy can create changes in emotional experience, that may further amplify issues such as difficult romantic relationships, family relationships, drug use, and insecurities, etc.

Planned pregnancy, physical health, social relationships, material conditions, and psychological preparedness are all known factors that lead to a positive emotional experience in pregnancy. For women struggling with active substance use, all or some of these factors may be absent, leading to a higher likelihood of a negative emotional experience (e.g. stress).

Negative experiences and stress may need to be addressed, as stress is a risk factor for substance use disorder development and vulnerability to relapse. Stressful life events are barriers to remission from drug use disorder both over the short term (i.e., during the same time period as the stressful events) and the longer term (i.e., years after experiencing the stressful events).

- STIGMA

-

The shame, blame, and guilt attached to addiction can be extremely strong for pregnant women and mothers. Substance use in pregnant Women suffering from substance use disorder are viewed more harshly than others, even in healthcare settings (Corse, McHugh, & Gordon, 1995; Ginsberg, Raffeld, Alanis, & Boyce, 2006). Lefebvre et al. (2010)

Pregnant women with substance use who develop distrust after from a negative experience with a healthcare provider become less receptive to needed health care. In a 2003 study on nurses’ attitudes toward mothers with substance use, 76% felt anger toward the mother regardless of their knowledge base or experience.

- FEAR

-

Women with children may be hesitant to seek treatment for fear of legal action and social service involvement. Some programs may seek to offer legal support to assist mothers who have had their children removed by social services.

The threat of punishment for substance use during pregnancy is known to stop women from seeking prenatal care. In cases where mothers have received no pre-natal care, the babies are 3x more likely to have a low birth rate, and 5x more likely to die in infancy. Prenatal care for women with substance use disorder can reduce the impact of substance use on the fetus, and can be used as an opportunity for providers to help connect pregnant women with specialized treatment for their addiction.

SUPPORTIVE MEASURES FOR PREGNANT WOMEN

- SUPPORTIVE RELATIONSHIPS

-

Research has shown that families can be a source of strong, positive support for mothers suffering from substance use disorder. Building and sustaining relationships with loved ones may encourage mothers to seek additional support beyond their immediate circles.

In addition, building rapport can enable useful communication in a population that may be reluctant to disclose their history. This can be done by:

- allowing the patient to speak uninterrupted

- summarizing what the patient said using their words

- maintaining eye contact

- active listening such as nodding

- asking clarifying questions

These common elements of good, person-centered, counseling, help build trust and patients’ engagement with care.

- PARENTING CLASSES

-

Classes that address parenting methods can be a strong resource for mothers.

Through classes, parenting can be taught as:

- Skills (e.g., interacting sensitively, facilitating sleeping and eating routines)

- Attitudes (e.g., empathy, positive approaches to behavior guidance)

- Knowledge (understanding child development)

- Capacity (e.g., maternal custody, lack of need for child protection services involvement).

- FAMILY INTEGRATION

-

Integrated treatment programs are programs that combine on-site pregnancy, parenting, or child-related services with addiction treatment services. Programs formulated to integrate children with mothers in addiction treatment began to emerge in the 1960s, but did not see widespread acceptance and adoption until more than three decades later in the 1990s.

Available evidence suggests that integrated treatment programs for mothers and their children are linked to:

- Improvements in parenting skills, which are shown to improve the prognosis and outcomes for both mothers and their children.

- Increased motivation to abstain from drug and alcohol use.

- Improvements for children in development, growth, emotional and behavioral functioning, in contrast to infants whose mothers were not enrolled in an integrative program.

DURING PREGNANCY (PRENATAL)

- PRENATAL HEALTHCARE

-

Conduct sexual health check-ups: from pregnancy (prenatal care), to family planning and protection, sexually transmitted diseases, and fluctuating hormonal levels. Services should be offered to women that address these unique health risks as part of a normal comprehensive physical checkup.

- MEDICATIONS

-

Medication Assisted Treatments

While no medications for substance use disorder have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat pregnant women with substance use disorder, it has been found that combining medications for opioid use disorder (e.g. methadone or buprenorphine), prenatal care, and a comprehensive treatment program can limit negative consequences on both mother and child.

Studies strongly support maintaining pregnant patients on opioid-agonist pharmacotherapy because withdrawal is associated with increased fetal morbidity, miscarriage, and relapse rates, therefore, detoxification while pregnant is not recommended.

- CO-OCCURRING DISORDERS

-

There is evidence to suggest that when mental health treatment is paired with prenatal care, abstinence rates increase.

LABOR AND DELIVERY

- PAIN MANAGEMENT

-

Long term use of opioids can result in opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH). This is characterized by hypersensitivity to pain which, when in labor, can be unbearable. Healthcare professionals should screen for, and be aware of, a patients substance use disorder and any medications that could affect the labor process.

If a patient is prescribed an opioid agonist, continue normal medications and enhance pain management care to address the acute pain of delivery. Pain management should be based on clinical assessment, not on prescribed maintenance doses.

Partial agonist/antagonist intravenous treatments should be avoided. Labor epidural or combined spinal/epidural forms of pain management are preferred, and healthcare providers should educate patients that total pain control may not be a realistic expectation due to increased tolerance from long-term opioid use.

For patients who use illicit benzodiazepines (common in patients who use opioids), treatment to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal may be indicated.

AFTER BIRTH (POSTPARTUM)

- BREASTFEEDING

-

Breastfeeding is compatible even when low levels of methadone or buprenorphine are present in the breast milk.

In less severe cases of newborns dependent on opioids, preliminary studies have explored the relationship between dependent mothers breastfeeding, with the breast milk containing traces of methadone or buprenorphine, and it’s effect on rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome problems and pharmacotherapy intervention.

Mothers prescribed medications for substance use disorder should be encouraged to postpone transitioning off of opioid agonist or partial agonist treatments until:

- a stable living environment free of drug related activity is found

- the infant sleeps through the night

- breastfeeding is completed

- sufficient recovery resources (“recovery capital”) to help sustain remission are available

For some patients, long-term opioid agonist treatment may be best. Clinical needs and patient motivation must all be considered in helping these patients maintain abstinence.

- POSTPARDUM DEPRESSION

-

After childbirth, mothers may fall into a depression that is characterized by helplessness, lack of emotional attachment to the baby, health deterioration, and thoughts of harming one’s self or the infant.

At an elevated risk for depression, mothers in active addiction or recovery, should seek out professional help. Counseling and/or therapy (e.g. cognitive behavioral therapy) can help address issues of both depression and substance use.

RESOURCES FOR WOMEN

- Women for Sobriety (peer Support group)

- Hazelden Betty Ford library collection of books for women

CITATIONS

- Research Summaries

-

- A Real-world Comparison of Methadone & Buprenorphine for Opioid-dependent Pregnant Women

- A Review of Naltrexone Effectiveness for Alcohol Use Disorder Among Women

- Good Idea? Bad Idea? Integrating Family Planning & Substance Use Disorder Treatment Services

- Using the Child Welfare System to Engage Parents with Substance Use Disorders

- Additional Citations

-

- Alexander, K. (2017). A Call for Compassionate Care. Journal of addictions nursing, 28(4), 220-223.

- Ashley, O. S., Marsden, M. E., & Brady, T. M. (2003). Effectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: A review. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 29(1), 19-53.

- Bateman, B. T., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Rathmell, J. P., Seeger, J. D., Doherty, M., Fischer, M. A., & Huybrechts, K. F. (2014). Patterns of opioid utilization in pregnancy in a large cohort of commercial insurance beneficiaries in the United States. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 120(5), 1216-1224.

- Brady, T. M., & Ashley, O. S. (2005). Women in substance abuse treatment: Results from the Alcohol and Drug Services Study (ADSS). Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies.

- Canidate, S.S., Carnaby, G.D., Cook, C.L., & Cook, R.L. (2017). A systematic review of naltrexone for attenuating alcohol consumption in women with alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, Mar; 41(3), 466-472. doi: 10.1111/acer.13313.

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance Abuse Treatment: Addressing the Specific Needs of Women. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2009. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 51.) Chapter 7: Substance Abuse Treatment for Women.

- Conway, K. P., Compton, W., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2006). Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry.

- Desai, R. J., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Bateman, B. T., & Huybrechts, K. F. (2014). Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstetrics and gynecology, 123(5), 997.

- Greenfield, S. F., Back, S. E., Lawson, K., & Brady, K. T. (2010). Substance Abuse in Women. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(2), 339–355. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004

- Green, C. A. (2006). Gender and use of substance abuse treatment services. Alcohol Research and Health: NIAAA Publication, 29(1), 55.

- Greenfield, S. F., Cummings, A. M., Kuper, L. E., Wigderson, S. B., & Koro-Ljungberg, M. (2013). A qualitative analysis of women’s experiences in single-gender versus mixed-gender substance abuse group therapy. Substance use & misuse, 48(9), 750-760.

- Hill, P. E. (2013). Perinatal addiction: Providing compassionate and competent care. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 56(1), 178-185.

- Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H. G., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological psychiatry, 61(3), 348-358.

- Jones, H.E., Deppen, K., Hudak, M. L., Leffert, L., McClelland, C., Sahin, L., Starer, J., Terplan, M., Thorp, J., Walsh, J., Creanga, A. A. (2014). Clinical care for opioid-using pregnant and postpartum women: The role of obstetric providers. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 210(4), 302-310.

- Kelly, J. F., Greene, M. C., & Bergman, B. G. (2018). Beyond Abstinence: Changes in Indices of Quality of Life with Time in Recovery in a Nationally Representative Sample of US Adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

- King, P. A. L., Duan, L., & Amaro, H. (2015). Clinical Needs of In-treatment Pregnant Women with Co-occurring Disorders: Implications for Primary Care. Maternal and child health journal, 19(1), 180-187.

- Marsh, J. C., Cao, D., & D’Aunno, T. (2004). Gender differences in the impact of comprehensive services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27(4), 289-300.

- Meyer, M. C., Johnston, A. M., Crocker, A. M., & Heil, S. H. (2015). Methadone and Buprenorphine for Opioid Dependence During Pregnancy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of addiction medicine.

- Milligan, K., Niccols, A., Sword, W., Thabane, L., Henderson, J., Smith, A., & Liu, J. (2010). Maternal substance use and integrated treatment programs for women with substance use issues and their children: A Meta-analysis. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 5, 21-35.

- Niccols, A., Milligan, K., Sword, W., Thabane, L., Henderson, J., & Smith, A. (2012). Integrated programs for mothers with substance abuse issues: A systematic review of studies reporting on parenting outcomes. Harm reduction journal, 9(1), 14.

- Niccols, A., Milligan, K., Sword, W., Thabane, L., Henderson, J., Smith, A., Liu, J., & Jack, S. (2010). Maternal mental health and integrated programs for mothers with substance abuse issues. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(3), 466-474.

- O’connor, A. B., Collett, A., Alto, W. A., & O’brien, L. M. (2013). Breastfeeding rates and the relationship between breastfeeding and neonatal abstinence syndrome in women maintained on buprenorphine during pregnancy. Journal of midwifery & women’s health, 58(4), 383-388.

- Persons, A. T. E. (2009). Trauma, post traumatic stress disorder, and addiction among women. Women and addiction: A comprehensive handbook, 242.

- Raeside, L. (2003). Attitudes of staff towards mothers affected by substance abuse. British journal of nursing, 12(5), 302-310.

- Robinowitz, N., Muqueeth, S., Scheibler, J., Salisbury-Afshar, E., Terplan, M. (2016). Family planning in substance use disorder treatment centers: Opportunities and challenges.Substance Use & Misuse, 51(11), 1477-1483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1188944

- Secco, L., Letourneau, N., Campbell, M. A., Craig, S., & Colpitts, J. (2014). Stresses, strengths, and experiences of mothers engaged in methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of addictions nursing, 25(3), 139-147.

- Sinha, R. (2001). How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse?. Psychopharmacology, 158(4), 343-359.

- Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons With Co-Occurring Disorders. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2013. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 42)

- Traube, D. E., He, A. S., Zhu, L., Scalise, C., & Richardson, T. (2015). Predictors of Substance Abuse Assessment and Treatment Completion for Parents Involved with Child Welfare: One State’s Experience in Matching across Systems. Child Welfare, 94(5), 45-66.

- Tyrlik, M., Konecny, S., & Kukla, L. (2013). Predictors of Pregnancy-Related Emotions. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, 5(2), 112–120. http://doi.org/10.4021/jocmr1246e

- Van Boekel, L. C., Brouwers, E. P., Van Weeghel, J., & Garretsen, H. F. (2013). Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 131(1), 23-35.

- Welle‐Strand, G. K., Skurtveit, S., Jansson, L. M., Bakstad, B., Bjarkø, L., & Ravndal, E. (2013). Breastfeeding reduces the need for withdrawal treatment in opioid‐exposed infants. Acta Paediatrica, 102(11), 1060-1066.

- Wilsnack SC. Barriers to treatment for alcoholic women. Addiction and Recovery. 1991;11(4):10–12.