12-step Versus Other Psychosocial Interventions for Drug Problems

Are 12-Step Interventions Better or Worse than Other Psychosocial Interventions for Drug Use and Social Outcomes?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Twelve-step programs are delivered in a variety of ways such as through peers in community-based mutual-help organizations, through clinicians delivering 12-step therapies in outpatient treatment clinics or through residential treatment approaches that incorporate 12-step principles and takes patients to meetings. 12-step programs, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), are free community resources that have been shown to reduce the burden on the healthcare system by increasing remission rates and are considered cost-effective interventions for alcohol use disorders.

The evidence for using 12 step programs for alcohol use disorder is strong. Twelve-step programs have been shown to be just as effective as other psychosocial interventions for drugs other than alcohol, too, but the strength of the evidence has been somewhat limited, to date, and further evidence is needed. Looking at these studies in aggregate can allow for stronger conclusions to be drawn about the effectiveness of 12-step programs at reducing illicit substance use and negative consequences, and to identify scientific gaps to inform future research in this area.

This aggregated summary of the research (i.e., meta-analysis) conducted by the research team was a systematic evaluation of 12-step interventions and treatment effects compared to either no intervention, psychosocial (i.e., non-medication) “treatment as usual,” or other alternative interventions, including medication with or without an additional psychosocial treatment.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis (statistical analysis of effects on illicit drug use) which resulted in 10 randomized control trials and quasi-experimental studies (9 in the synthesis) that compare outpatient treatments or treatments based on 12-step programs to alternative interventions, all of which are manual-based interventions. Separate meta-analysis were run for the treatment phase, at treatment end, 6 and 12-month follow-up. A total of 1,071 participants with a drug use disorder were included across all studies included in the review. The primary outcome was illicit drug use (biochemical test or self-reported estimates of drug use). Secondary/social outcomes included criminal behavior, prostitution, psychiatric symptoms, social functioning, employment status, homelessness, and treatment retention.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

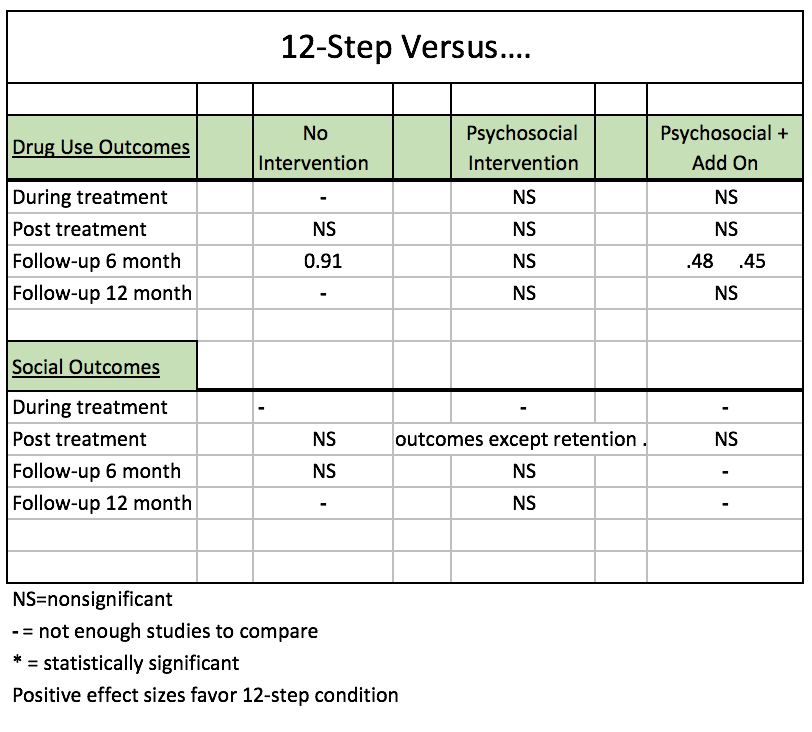

Overall, 12-step manualized interventions and treatments for reducing illicit drug use were associated with similar health improvements compared to the other interventions. Notably, when 12-step facilitation was delivered with 12-step therapeutic content, a disease model of addiction, and a disulfiram add on, it had stronger effect (.48) on reducing illicit drug use than alternative interventions (i.e., clinical management or treatment as usual with disulfiram add-on) at 6-month follow-ups (see Table 1). The same was found at 6-months (.45) when 12-step facilitation with disulfiram add-on was compared to clinical management with disulfiram add-on and when 12-step facilitation with placebo add-on was compared to treatment as usual with placebo add on.

Additionally, a sizeable effect (.91 which favored 12-step) was found for reducing illicit substance use when comparing a 12-step intervention to no intervention at 6 months, however this finding was based on a single available study. 12-step outpatient interventions and treatments performed the same as alternative active treatment conditions on social outcomes including criminal behavior, prostitution, psychiatric symptoms, social functioning, employment status, homelessness, with the exception of treatment retention. The analysis did not show that 12-step interventions or treatments performed worse than any other alternative condition.

Table 1: Effect sizes comparing 12-Step conditions to alternative conditions.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This systematic analysis found that outpatient 12-step treatments were as effective as alternative psychosocial interventions in reducing drug use during treatment, post treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. 12-step treatments combined with add on did confer benefit at 6-month follow-up, but this finding disappeared at 12-months and is based on only a few studies. This shows that 12-step manualized interventions delivered by a trained therapist are a legitimate treatment option to reduce illicit drug use among those with a drug use disorder -as good as anything else.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- One study not included in this review, however, called the cocaine collaborative treatment study found that a 12-step facilitation treatment approach in the treatment of patients with cocaine use disorder (called “individual drug counseling”) outperformed both cognitive-behavioral treatment and a psychodynamic approach (i.e., an emotion and relationship-focused therapy) called supportive-expressive therapy. Of note, in that study individuals in all three treatment groups in that study also received group therapy where patients received psychoeducation about the nature of substance use disorder and were encouraged to attend 12-step meetings. This study could have been missed by the authors in their search for relevant studies as the intervention in the cocaine study was called “Individual Drug Counseling”, and it may not have been obvious that this was a 12-step intervention.

- Also, importantly, the authors did not examine the proportion of patients who were completely abstinent or in remission at each follow-up, nor did they discuss the potential of health care cost savings. Studies with alcohol use disorder patients, for example, have found that 12-step treatments tend to produce substantially higher rates of continuous abstinence and remission among patients and because 12-step mutual-help participation is free, there can be large health care cost savings as well.

- The strength of the evidence is weak because statistical ability to detect a significant difference in the pooled meta-analysis was low due to few studies that met inclusion criteria.

- There were many time points which had no available studies to analyze, such as during treatment and at 12-month follow-up for 12-step versus no intervention groups. Therefore, conclusions can not be drawn about these time points and specific comparison conditions.

- The authors did not examine the proportion of patients in each study that had continuous abstinence. This should be examined because patients with alcohol use disorder who receive 12-step treatments have been shown to have substantially higher rates of abstinence compared to other interventions (e.g., CBT).

- The authors did not address the issue of health care cost offsets, or other cost-savings that might accrue if patients were directed to freely available mutual-help resources. Studies have found for example, that patients receiving 12-step treatments in the VA system tend to have higher continuous abstinence rates and substantially reduced health care costs (Humphreys & Moos, 2001; Humphreys & Moos, 2007).

- Despite the fact that some effect sizes were small, some studies failed to statistically adjust for the fact that the intervention is administered to groups as opposed to individuals, and thus may overestimate effects.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Although the strength of the overall evidence is weak due to few studies to compare and small effect sizes, the results of this meta-analysis suggests that 12-step treatments perform as well as other psychosocial treatments. Furthermore, the proportion of patients completely abstinent at follow up was not tested but this has been shown to be an outcome that favors 12-step participation among patients with alcohol use disorder. So if you or someone you know are inclined to prefer the 12-step model for reducing illicit drug use this study shows it is an empirically supported approach.

- For scientists: The main results of this meta-analysis showed mostly no difference in the effectiveness of 12-step treatments compared to alternative psychosocial interventions in reducing drug use or negative social outcomes at any time point. These results are based on relatively few studies and many time points did not have any studies to analyze. More research is needed to make stronger conclusions about the effectiveness of 12-step interventions for drug use disorders other than alcohol given the unclear picture and small effect sizes that were detected at 6 months. Furthermore, 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder have been shown to produce much bigger rates of continuous abstinence relative to other psychosocial interventions. Future studies on drug using populations should examine this outcome as well.

- For policy makers: This meta-analysis found that manualized 12-step treatments delivered by a trained therapist performed about the same as psychosocial treatment, and better than psychosocial treatment with various add ons (i.e., medications and placebo) by 6 months. This shows that 12-step treatment may offer a cost-effective alternative to other psychosocial treatments with add ons and should be considered as a viable treatment option to reduce illicit drug use. While much is known about 12-step mutual-help and facilitation approaches for alcohol use disorder, research funding is sorely needed to support further study into examining these easily accessible, community-based resources for illicit drug use disorder including opioid, cocaine, and marijuana.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This systematic evaluation of 12-step treatments compared to either no treatment, treatment as usual (a psychosocial intervention), and alternative interventions (with pharmaceutical or other psychosocial add-ons) found that 12-step approaches produced similar reductions in illicit drug use and negative social outcomes when compared to psychosocial interventions such as clinical management and treatment as usual. While more research is needed, based on available research, when considering a psychosocial approach for illicit drug use disorder, you may confidently integrate 12-step facilitation approaches into your treatment program.

CITATIONS

Bøg M, Filges T, Brännström L, Jørgensen AMK, Fredriksson MK. 12-step programs for reducing illicit drug use: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2017:2 DOI: 10.4073/csr.2017.2