Medical conditions are more common among individuals who have resolved a substance use problem

Original Research From the Recovery Research Institute

Addiction can lead to or worsen many medical conditions, but until now it was not necessarily known if those in recovery from significant alcohol or other drug problems have higher rates of disease than the general U.S. population. The present study shows that in fact they do.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

It is widely appreciated that the long-term use of alcohol and other drugs gives rise to a wide variety of medical conditions. What is not well understood is to what degree individuals in addiction recovery are affected by disease compared to the general population. In addition to answering these questions, this study also investigated how having medical conditions affected quality of life.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

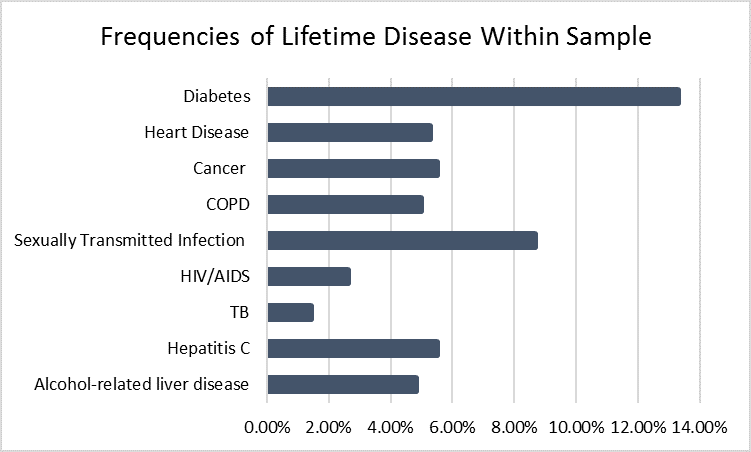

Data from the National Recovery Survey was used in this study. The National Recovery Survey assessed 2,002 U.S. adults who answered yes to the question, “Did you used to have a problem with alcohol or drugs but no longer do?” Participants were asked a number of questions including whether they had ever been told by a healthcare provider if they had 1 or more of 9 medical conditions including alcohol-related liver disease, hepatitis C, tuberculosis (TB), the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), another sexually transmitted infection, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, heart disease, or diabetes. Quality of life was measured using the EUROHIS-QOL—a widely used 8-item measure of quality of life, adapted from the World Health Organization Quality of Life—Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF).

Where possible, the frequency of specific diseases in the National Recovery Survey sample was compared to the general U.S. population using the Centers for Disease Control Prevention’s, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) dataset. Comparisons were made using age-standardization; a way of statistically controlling for differences between ages between the two samples.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Relative to the general population, prevalence of hepatitis C, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, and diabetes were greater in the National Recovery Survey sample. Direct comparison between the National Recovery Survey and NHANES general population datasets was not possible for alcohol-related liver disease, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted infections, and cancer, as the NHANES survey either did not assess for these diseases or assessed them in ways different to the National Recovery Survey.

Though direct comparisons were not possible for these specific diseases, the authors noted that the National Recovery Survey sample experienced rates for these diseases at least comparable with previously reported estimates for the general population, and in some instances, notably greater. For instance, the cancer prevalence rate in the National Recovery Survey sample (5.50%) was slightly higher, but comparable, to estimated prevalence rates in the general population (4.80%). The incidence of HIV/AIDS, however, appears to be 7 to 8 times higher in the National Recovery Survey sample (2.6%), compared with the general population (0.34%), though it is important to note that the Centers for Disease Control Prevention estimates are for 2015 (vs 2016 for the National Recovery Survey sample) and include people aged 13 and older (vs 18 and older for the National Recovery Survey sample). Regarding tuberculosis, 1.42% of this National Recovery Survey sample endorsed being told by a healthcare professional that they have this disease. This is comparable to findings from the 2011 to 2012 NHANES for a positive response to a tuberculosis skin test (1.40%), but higher than the rate of NHANES participants endorsing being told by a healthcare provider that they have active tuberculosis (0.39%), and lower than NHANES participants having a positive tuberculosis blood test (5.82%).

The authors also found that individuals who primarily used classes of drugs commonly associated with injection, such as opiates or stimulants, had higher rates of diseases known to be transmitted by sharing needles, including hepatitis C and HIV.

Participants primarily using stimulants like amphetamines also had higher rates of sexually transmitted infections than those for whom alcohol was primary, which supports previous findings reporting higher incidence of sexually transmitted infections among individuals who use stimulants (particularly methamphetamine) who are believed to engage in greater and/or more risky sexual activity than individuals who don’t use stimulants. Surprisingly, those for whom cannabis was primary were not different in terms of rates of alcohol-related liver disease compared with those for whom alcohol was primary.

Finally, as the authors predicted, quality of life was lower among those with physical disease histories relative to those without.

Figure 1.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

In combination with other epidemiological and clinical findings regarding the harmful impact of alcohol and other drug use on health, this study suggests the need for earlier and more assertive intervention to help reduce medical disease burden, and underscores the need for better integration of medical and substance use disorder services.

Such services should include assertive linkage by healthcare providers to comprehensive medical and psychosocial recovery management, given more passive linkage has had limited effect on patient treatment engagement and not shown significant long-term benefit in terms of addiction recovery outcomes. Further longitudinal research is needed that can help uncover the relationships between alcohol and other drug use and the onset of various medical conditions over time. Such research will help us to better understand the time-course of these diseases, both in terms of their onset, persistence and resolution, before, during and after addiction recovery is achieved.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the authors:

- The data reported in this study are cross-sectional and reflect lifetime occurrence of disease. It is possible that some study participants may have developed these diseases before developing a problem with alcohol and other drugs.

- There is no way to know whether these medical conditions resolved or improved after individuals’ alcohol and other drug problems were resolved, and how present quality of life temporally aligns with participants’ disease history.

- Relatedly, while having a disease/s was related to lower quality of life, it is possible that other factors also associated with having a disease such as lower household income and education were also influencing participants’ quality of life.

- The National Recovery Survey study’s stem question (‘‘Did you used to have a problem with drugs or alcohol but no longer do?’’) was designed to capture the broader population of individuals affected by alcohol and other drug problems, including those who have not been formally diagnosed with substance use disorder, but whose alcohol and other drug problems nevertheless contribute to addiction disease burden. An inherent strength and limitation of this approach is that the specific parameters of what constitutes an alcohol and other drug problem and overcoming an alcohol and other drug problem are determined subjectively by the participants.

- Although the total sample size was large, the prevalence of a number of conditions was quite low. As such, the authors may have been underpowered to detect differences between some subgroups.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Medical conditions related to problematic alcohol and other drug can greatly compound the overall burden felt by sufferers. Individuals in addiction recovery are likely to benefit from regular medical check-ups and accurately reporting their history of substance use involvement to their doctor to ensure appropriate medical tests are conducted (e.g., testing for hepatitis C for people with a history of injecting drugs; liver tests for individuals with history of heavy alcohol use). Also, long-term addiction recovery support from treatment providers like psychologists, social workers, and medical doctors may help individuals better cope with the burden of disease.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Medical conditions related to problematic alcohol and other drug use can greatly compound the overall burden felt by sufferers. Healthcare providers can begin to reduce this burden by engaging individuals with histories of problematic substance use with long-term recovery management, and encouraging patients to seek regular medical check-ups. More assertive medical interventions could also be incorporated into outpatient and inpatient addiction treatment, as well as into long-term recovery management programs. Further, individuals currently struggling with alcohol and other drug problem will benefit from better integration of addiction treatment in primary care medical settings.

- For scientists: Longitudinal research is needed that can help uncover the complex relationships between alcohol and other drug use and the development of medical conditions over time to improve our understanding of their related trajectories, and how medical sequelae of alcohol and other drug problems potentially resolve in substance use disorder remission. There is also a critical need to develop ways to integrate addiction treatment and recovery management with medical care.

- For policy makers: Alcohol and other drug addiction exacts a prodigious burden on the individual and society. For many, this burden is greatly compounded by medical conditions arising from problematic substance use. The burden from substance use and related medical conditions can be ameliorated by improving access to long-term addiction recovery management, and medical health care for individuals in recovery by supporting treatment programs, improving individuals’ access to health insurance, and implementing policies that require coverage of long term recovery management for substance use disorder rather than short term acute stabilization only.

CITATIONS

Eddie, D., Greene, M. C., White, W. L., & Kelly, J. F. (In press). Medical burden of disease among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug problems in the United States: Findings from the National Recovery Survey. Journal of Addiction Medicine.