Medications for opioid use disorder: Do they predict success in treatment settings?

Individuals with an opioid use disorder (OUD) typically benefit from empirically supported agonist medicines (such as buprenorphine or methadone) and antagonist medicines (such as depot naltrexone). And yet, many individuals do not receive or persist in these treatments for a variety of reasons. This study examined whether including medication for OUD in an individual’s treatment was associated with longer treatment retention and higher treatment completion as well as whether state coverage of medication influenced this relationship.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Empirically supported medicines such as buprenorphine or methadone can support recovery from an OUD by increasing an individual’s ability to engage and stay in treatment and by reducing adverse consequences such as overdose. Those with an OUD who remain in treatment and receive the planned dose of medication have better outcomes, and data suggests that retaining people on these medications for extended periods (i.e., at least 6 months), is necessary to significantly reduce relapse and also mortality risk. Yet, many individuals do not receive or persist in these treatments, outcomes which vary between individuals by age, racial/ethnic background, and insurance coverage, to name a few. Examining how medications to treat OUD are associated with treatment completion and retention in real-world clinical samples can provide important information about how well medication receipt and retention happens in practice. As well, understanding what system-level factors (e.g., state funded insurance) support continued access to these forms of treatment can help to identify disparities in access.

To address these gaps, this study examined whether treatment included medication for OUD, and if so, this resulted in longer substance use treatment retention and greater chance of treatment completion. In addition, the study examined whether state Medicaid coverage of medication for OUD influenced the relationship between these factors.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary data analysis using a national cross-sectional sample of all opioid-related discharges in the 2016 National Treatment Episode Dataset – Discharges (TEDS-D) sample. The dataset captured 1,452,318 total discharges during 2016. The sample was further restricted to select only those cases likely to be relevant, by including only cases where heroin or opioids/synthetics were reported as the primary, secondary, or tertiary substance at admission, cases from outpatient settings, and cases without missing treatment plan data. As result, the final sample for this analysis included 152,196 opioid-related discharges from 47 U.S. states (Georgia, Oregon, and West Virginia did not report a sufficient amount of data to be included in the dataset). The study also used state-level aggregate measures of demographics from the 2010 census and a 2015 review of state level Medicaid coverage policies.

The inclusion of medication for OUD treatment was used to predict separately the primary outcomes of interest: treatment completion and treatment retention. Including medication for OUD in treatment was operationalized for the analysis as the presence of medications for OUD treatment (“such as methadone or buprenorphine”) in a patient’s treatment plan. Treatment plans are often developed collaboratively by the clinical team and patient after a thorough evaluation of the patient’s clinical history and needs.

Treatment completion was based on the documented reason for discharge (7 options including “completed”, “left against professional advice”, “death”, “incarceration”) which were then dichotomized to be favorable (patient completed treatment) versus unfavorable (patient did not complete treatment).

Treatment retention was measured with two thresholds; (1) length of stay in treatment longer/shorter than 180 days and (2) length of stay longer/shorter than 365 days.

In follow-up analyses, they examined whether state-level Medicaid coverage of methadone for treatment (as of September 2015) influenced the relationship between a treatment plan’s inclusion of medication for OUD and client retention/completion. They expected that patients in states with methadone Medicaid coverage would have a stronger relationship between receiving OUD medication and treatment completion and retention given that medication would be more accessible. The authors also used several control variables in the analysis to try to isolate the effects of including OUD medication in the patient’s treatment. These variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity and several state-level demographics (percentage male, percentage non-Hispanic white, percentage of age 10-24, percentage without high school education, and state population).

The study sample included 152,196 opioid-related discharges from 47 states in 2016. These discharges were among primarily male (60%) and non-Hispanic white (70%) individuals. Of these discharges, the majority (86%) were located in states with Medicaid coverage of methadone treatment. Only 43% of discharges included medication in the treatment plan.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Only 1/3 of OUD patient discharges successfully completed treatment.

Only 30% of individuals were retained in treatment for at least 180 days. Among those who were in treatment for 180 days, only 36% were determined to have completed treatment and for those who were in treatment >365 days, only 32% were determined to have completed treatment.

Medication for OUD in treatment plans was linked to an increased likelihood of treatment retention.

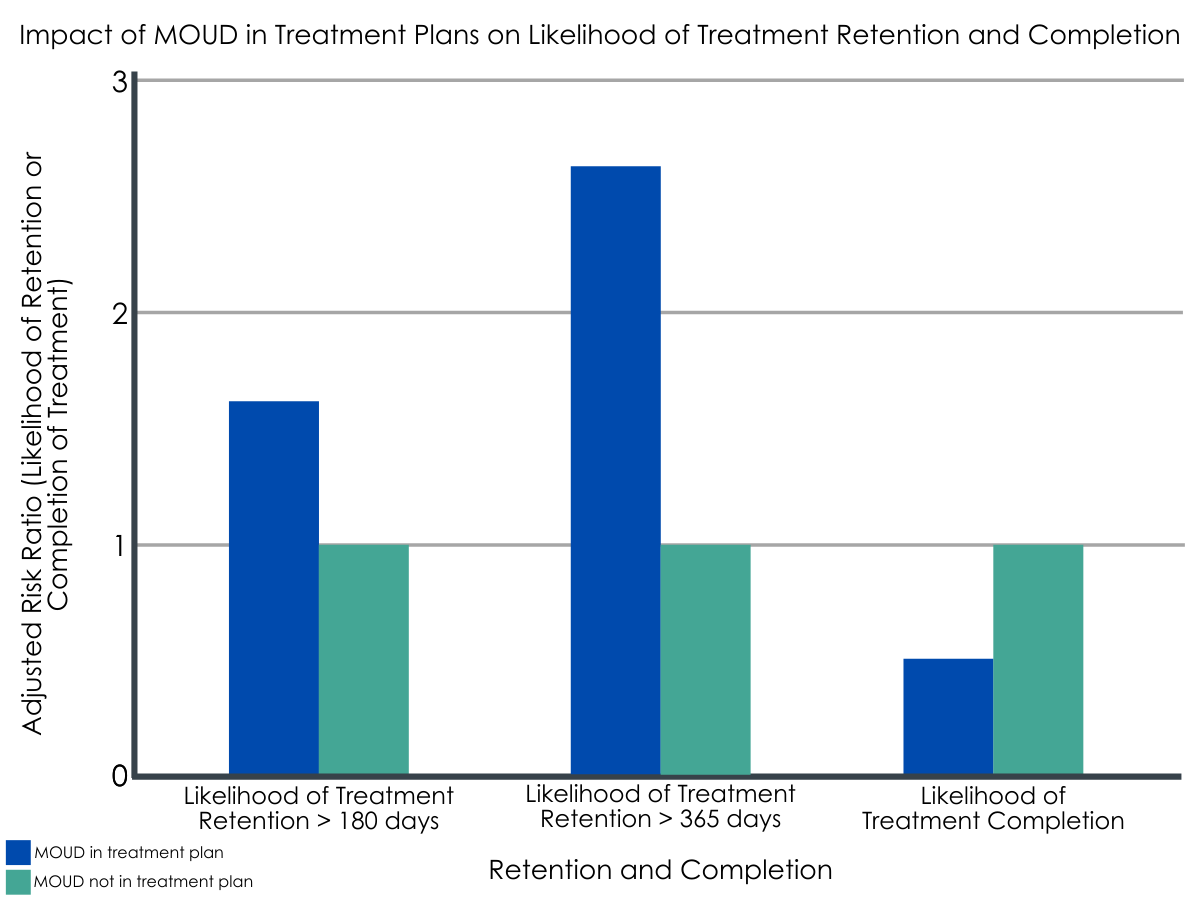

Askari and colleagues hypothesized that medication for OUD in treatment plans would increase the likelihood of treatment retention at >180 days and >365 days, independent of substance use treatment completion, and this was supported in the analysis. That is, those with medication for OUD in treatment plans were 60% and 164% more likely to be retained in treatment at >180 days and >365 days, respectively.

Figure 1. Researchers used adjusted risk ratios (aRR) to compare study groups. Compared to a baseline of Medication for OUD (MOUD) not being included in a treatment plan (aRR of 1), participants with MOUD included in a treatment plan had a higher likelihood of treatment retention, but a lower likelihood of completing treatment.

Medication for OUD in treatment plans was linked to a decreased likelihood of treatment completion.

Although Askari and colleagues hypothesized that having medication for OUD in individual treatment plans would increase likelihood of treatment completion; they found that having medication for OUD in individual treatment plans decreased the likelihood of substance use treatment completion based on discharge reason. That is, while 30% of discharges indicated that treatment was completed, the rate of completion for those without medication for OUD included in a treatment plan was 39%, while the rate for those with medication for OUD included in a treatment plan was only 17%. The fully adjusted models – which controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity and several state-level demographics – supported this trend; those with medication for OUD in treatment plans were 54% less likely than those without to complete treatment.

Medicaid methadone coverage was associated with increased inclusion of OUD in treatment plans but did not significantly alter the relationship between including medication for OUD in treatment plans and treatment completion/retention outcomes.

Discharges that included medication for OUD in the treatment plan were three times higher in states with Medicaid methadone coverage (48%) compared to states without Medicaid methadone coverage (16%).

Figure 2.

Although states with Medicaid methadone coverage had higher rates of including medication for OUD in treatment plans, after accounting for other individual- and state-level characteristics, the authors did not find evidence that Medicaid methadone coverage had additional influence on the relationship between having medication for OUD in treatment plans and treatment completion or retention.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study found that medication for OUD documented in individual treatment plans decreased the likelihood of substance use treatment completion, but alternatively, increased the likelihood of substance use treatment retention. This finding suggests that because treatment retention but not completion is increased, individuals are initiating and maintaining necessary treatment, a finding other research suggests reduces their likelihood of drug-related death. Therefore, these findings suggest that when medication for OUD is included in treatment plans, individuals in treatment are likely to fare better than when it is not included because they are more likely to stay on the medication for longer and thus more likely to refrain from using OUDs.

It is important to note that while medication for OUD documented in individual treatment plans decreased the likelihood of treatment completion, this may actually be a positive finding. That is, the severity of one’s condition could warrant ongoing medication and thus treatment completion is not the end goal. In this example, retention in necessary treatment due to OUD severity would be preferable to completing (ending) that necessary treatment. Yet, without knowing other key factors related to these discharges, it is difficult to extrapolate further from this study. That is, there could be differences in treatment retention and completion due to whether or not these discharges represent unique individuals (versus several repeat visits), the provider-suggested length and dose of treatment, or the quality and characteristics of the programs for the patients associated with each of these discharges. This uncertainty suggests it would be beneficial for stakeholders to examine all factors related to the OUD treatment experience and capture both retention and completion when conducting casual analyses of treatment system processes.

Given that the use of these medications in treatment for OUD reduce one’s risk of death by overdose as well as reducing other risk factors, it seems that ensuring that treatment plans include these components, where necessary, is vital. Overall, the findings support increasing structural factors to improve access to medication for OUD treatment, such as by ensuring state-level Medicaid coverage of such treatments and expanding the provider base by offering training and increasing the number of providers who include this in their treatment services.

As well, because treatment plans are a collaborative effort between the patient and providers, this study does not uncover why only 43% of individuals with an OUD had a treatment plan that included medication, and furthermore, why there were such low rates of retention among those with OUD in their treatment plan; this could be due to other factors including attitudes toward the medications of the patients and providers themselves. Thus, simply increasing structural supports for medication in OUD treatment may not fully drive patient or provider buy-in for the use of medication in treatment plans. Further research into factors that influence the inclusion of medication in a treatment plan may help to identify solutions to address structural and individual barriers.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The analysis did not include health insurance as it was not mandatory to complete and, likely as a result of this factor, was mostly missing (69%); health insurance is an important factor to control for in this type of analysis. Especially if medication for OUD is not covered for the entire length of the recommended treatment, this could be one primary reason for poor treatment retention or completion.

- It is possible that the analysis does not properly account for multiple opiate-related discharges for a single person because the dataset did not link discharges to patients; however, the authors used sensitivity analysis to examine this issue, suggesting this factor did not overly influence the findings.

- The study is missing other important information about both patient comorbidities and details on the treatment plans that may help to further delineate implications from these findings: TEDS-D did not include information about the intended time for medication for OUD treatment (time limited vs. long-term maintenance), dose, type of medication for OUD, or severity of OUD, factors that would all play a role in treatment retention and completion outcomes.

- The quality and completeness of TEDS-D records varies by State, a factor that could introduce bias in the analysis especially for states with variable policies on medication for OUD.

BOTTOM LINE

This study used a national sample of opioid-related discharges in 2016 and found that treatment plans that included medication for OUD had a decreased likelihood of substance use treatment completion and an increased likelihood of treatment retention. In other words, patients with OUD were more likely to stay in treatment rather than end treatment if they had an OUD medication as part of their treatment, which is consistent with best practices for OUD – to continue use of medication over the longer term. The study also found that states with Medicaid coverage of methadone treatment were more likely to include medication for OUD in treatment plans, but that this factor did not influence the relationship between medication for OUD in treatment plans and substance use treatment retention or completion.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: It is likely that additional education and outreach that relays the benefits and safety of medication treatment for OUD may improve access to and treatment retention in these services. As well, patients may need to look specifically for providers who offer these services, and providers may need to help patients to identify sources of insurance support and coverage to ensure they are able to follow a treatment plan that incorporates the use of medication. One further intervention opportunity may be to have peers in recovery help to identify and engage individuals with OUD who are not currently in treatment to engage with treatment.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Given the life-saving properties of some medications for OUD treatment, it is important to ensure that patients can access providers who support their use of medication as part of a treatment plan. It is likely that additional training and education that relays the benefits and safety of medication treatment for OUD may improve treatment planning and patient access to these services. There is also a need for clinical systems and staff who serve patients to actively implement strategies to understand and address perceived barriers to use of medication to treat OUD. For example, the use of culturally sensitive patient-centered approaches may assist with increasing treatment retention. As well, utilizing peer recovery support staff in these settings may help to engage otherwise unwilling individuals in initiating treatment.

- For scientists: This study attended to system level factors and incorporated state-level demographics and policies into the analysis – all strengths when considering that individual recovery occurs within this larger context. As the authors note, it will be important for future research to look at a variety of outcomes in addition to treatment completion, such as treatment retention and engagement. However, given the limitations noted, for future analyses to provide additional understanding, the definitions of retention and completion should take into account what length of treatment time is desirable, as well as severity of addiction and medication dose and type, and treatment program characteristics.

- For policy makers: This study highlights the importance of a variety of structural factors that can influence retention and completion of treatment. These factors include statewide policies, which can increase access to treatment coverage by reducing financial barriers, especially for the most vulnerable patients. They also include ensuring adequate training and provider capacity so that individuals with insurance coverage are able to access treatment in a timely manner and without encountering additional logistical barriers (location, transportation, etc.).

CITATIONS

Askari, M. S., Martins, S. S., & Mauro, P. M. (2020). Medication for opioid use disorder treatment and specialty outpatient substance use treatment outcomes: Differences in retention and completion among opioid-related discharges in 2016. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 114, [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108028