“Stay in touch”: Phone- and text-based continuing care check-ins after residential alcohol use disorder treatment

Continuing care is critical for helping prevent alcohol use disorder relapse risk following residential treatment. Yet because of limited resources, many residential treatment programs do not offer follow-up with their patients. This study tests whether resource-light follow-up approaches using infrequent phone calls or text messages can improve continuing care outcomes compared to more resource-heavy frequent provider phone check-ins.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Increasingly, providers and treatment systems are recognizing that as a chronic condition, a continuum of care is needed to successfully treat alcohol use disorder. Traditionally, continuing care following residential treatment has included things like outpatient therapy (both individual and groups). For a variety of reasons, however, these traditional options are not accessible or desirable for everyone. Increasingly, treatment programs are looking to lower cost, easy access post-residential treatment recovery support options such as recovery management checkups, check-ins over the telephone, and relapse prevention smartphone apps. The general scientific consensus is that systematic continuing care outperforms no continuing care and general support groups. However, following up with patients in these ways can still require a lot of resources at the end of the treatment program, and may also be experienced as burdensome to some patients.

In this study from Switzerland, the research team followed a sample of patients for 6 months following completion of 12-week, residential alcohol use disorder treatment program, who received either high-frequency phone check-ins, low-frequency phone check-ins, high-frequency text message check-ins, or no check-ins (controls).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a randomized controlled trial with 240 participants followed for 6 months after completing residential treatment for alcohol use disorder, receiving either, 1) high-frequency, phone call check-ins by the patients’ therapist, with weekly contact within the first month following treatment discharge plus additional call for 6 months, totaling 9 calls altogether, 2) low-frequency, phone call check-ins by the patients’ therapist, constituting a call every other month, 3) high-frequency, monthly text message check-ins with the option to call the patients’ therapist, which included 9 texts over 6 months, or 4) no check-ins (control group).

Figure 1.

Study outcomes included, 1) alcohol abstinence (yes/no) and time to first drink following treatment, 2) alcohol-related self-efficacy assessed using the question, “How confident are you that you will achieve your drinking goal?” with responses from 1 to 100, 3) employment status, 4) relationship and living situation, 5) engagement with additional continuing care, 6) physical and mental health, 7) depression symptoms, and 8) drinking goals.

Inclusion criteria included, 1) a minimum age of 18 years, 2) diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, 3) completion of residential treatment, and 4) a goal of alcohol abstinence at treatment completion. Exclusion criteria included, 1) use of drugs other than alcohol, 2) cognitive impairment, 3) insufficient knowledge of the German language to fill out questionnaires, 4) undertaking assisted living or day clinic treatment after inpatient treatment, and 5) not owning a mobile phone. For the phone call groups, calls were provided by patient’s primary therapist from their time in residential treatment. The therapists’ goals in these calls were to be supportive, empathic, helpful, and pragmatic without intrusive questioning or blaming for relapse. Call contents consisted of several cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) components, including monitoring of substance use status, identification of current and anticipated high-risk situations, and the development and rehearsal of improved coping behaviors. Each call lasted approximately 30 minutes. Patients who could not be reached received a minimum of 5 call attempts.

For the text message group, text messages were sent to check whether the patient was achieving their goal of abstinence. The patient could answer the question regarding abstinence with J (Yes), N (No), or U (I need support). A J-response triggered an automatic feedback message to congratulate the patient and motivate them to continue with their abstinence goal. In the case of a response indicating alcohol use lapse (N), or asking for support (U), or no response within 48 hours, the psychotherapist was informed by email to contact the patient by telephone within 24 hours. These telephone calls were based on the same components as described in the telephone interventions.

All patients had the opportunity to contact the psychotherapist any time during the 6 months if they needed support.

Fifty-one patients (21.2%) were assigned to the high-frequency telephone group, 64 patients (26.7%) to the low-frequency telephone group, 61 patients (25.4%) to the text message group, and 64 patients (26.7%) to the control group. Study participants were on average 50 years old, and 69% were male, and 62% were employed.

Patients in the intervention groups and control group did not differ in the demographic or clinical characteristics assessed at baseline or telephone reachability over 6-month.

For the high-frequency telephone group, of the 459 scheduled phone calls (51 patients x 9 monitoring dates), 88.5% phone calls were successful, while 10.0% calls remained unanswered. No patient made use of additional support.

For the low-frequency telephone group, of the 128 scheduled phone calls (64 patients x 2 monitoring dates), 88.3% of phone calls were successful, whereas 8.6% remained unanswered. One patient contacted the psychotherapist 6 times for additional support.

For the text message group, 94.8% responded regularly to the monitoring questions. Out of the 522 messages sent by the system (58 patients x 9 monitoring dates), 76.4% were responded with the text message that the patient remained abstinent, 13.4% with the message that they relapsed, and 3.3% with the message asking for support. Thirty-six (6.9%) messages were not responded to. A total of 123 phone calls were attempted to patients who reported a lapse, did not reply, or asked for support. Of these phone calls, 36 were unsuccessful. One patient contacted the psychotherapist once for additional support.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

High-frequency phone call participants had better abstinence rates, but not time to first drink compared to controls.

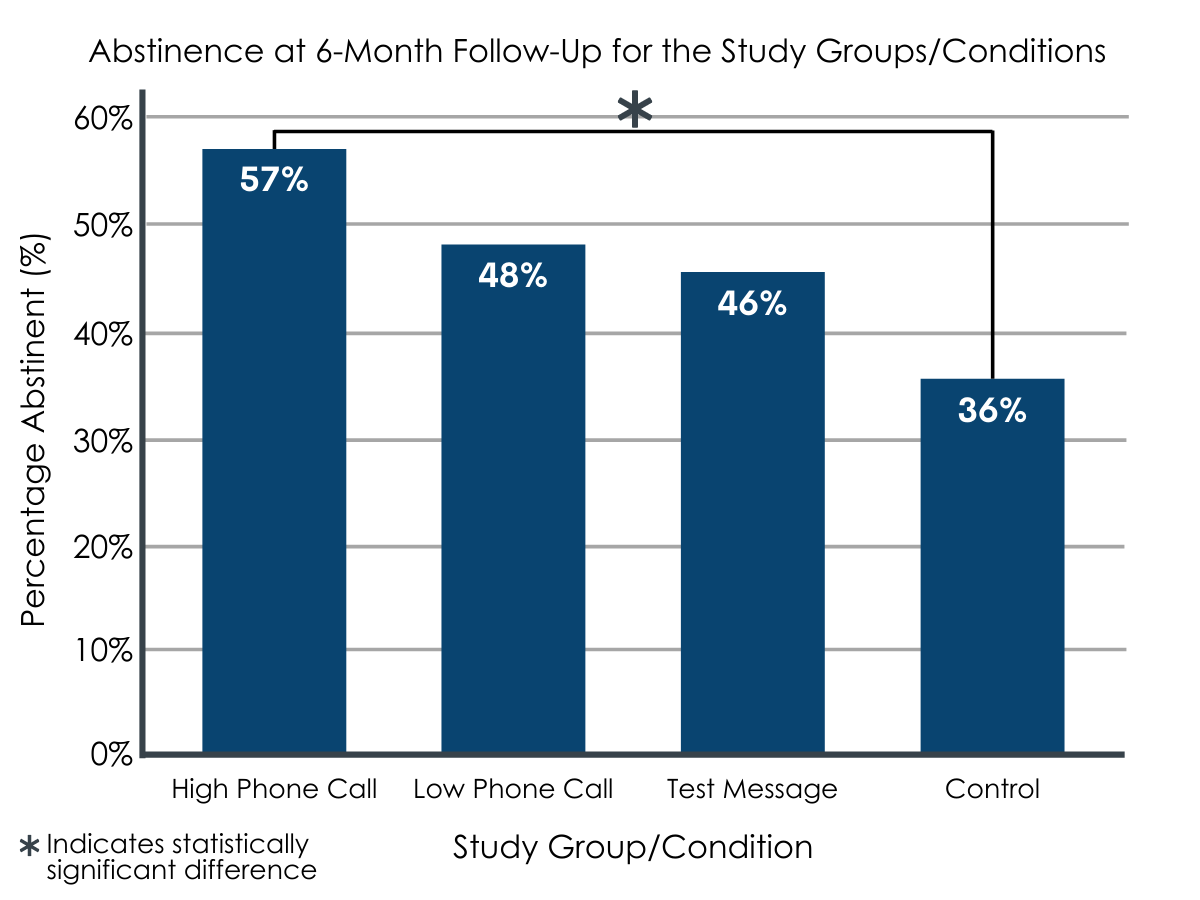

Statistical analyses comparing the different intervention groups on alcohol abstinence status over the course of the 6-month follow-up period indicated that those in the high-frequency phone call group were statistically significantly more likely to have been abstinent over the course of the 6-month follow-up period than controls (57% vs. 36%), meaning there was a high probability that the difference in abstinence rates between these groups was not due to chance alone.

Figure 2. Abstinence at 6-month follow-up for the study groups/conditions. The difference between the High-Frequency Phone Call and Control conditions was found to be statistically significant.

However, differences in number of alcohol lapses between the two other experimental groups and the control group were not statistically significant.

In terms of time to first drink, no group did statistically significantly better than the other. In other words, groups were roughly equivalent in terms of time to first drink following residential treatment.

High-frequency phone call and text message participants had greater alcohol-related self-efficacy, but not functioning outcomes, than controls.

Patients in both the high-frequency telephone group, and text message groups both reported significantly higher alcohol-related self-efficacy, or confidence to remain abstinent, compared with the control group at 6-month follow-up.

At 6-month follow-up, the intervention groups did not significantly differ from the control group regarding employment, relationship and living situation, additional continuing care, physical and mental health, depression, and drinking goals.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Findings in this study support previous work suggesting that regular check-ins with patients following residential alcohol use disorder treatment can help individuals sustain gains made in treatment. This is good news because it shows that meaningful improvements in treatment outcomes can be produced with a relatively uncomplicated low-intensity intervention. Though these kinds of phone check-ins can be taxing on the resources of treatment programs, these costs are well offset by the clinical benefit conferred to patients and the long-term cost savings cost to healthcare systems. The research to date suggests that initial investments in these types of regular, structured post-treatment check-ins are likely to pay for themselves over time while decreasing alcohol consumption and related harms.

High frequency phone check-ins conferred clear benefit in terms of 6-month abstinence outcomes compared to no intervention (controls), in terms of maintaining alcohol abstinence, the results of this study showed that high frequency calls didn’t significantly outperform high frequency text messages or low frequency calls every other month, suggesting high frequency calls aren’t necessarily better than lower frequency calls or text messages. This finding, however, is complicated by the fact that high frequency text messages or low frequency calls didn’t do significantly better than no contact (control group), even though they appeared to do better descriptively. This may have been due to the fairly small sample size in each group, which would have reduced the researchers’ ability to detect a statistically significant effect, especially if the effect is small and variable. All this, however, doesn’t detract from the key finding here, that checking in with patients regularly over a 6-month period led to clinically meaningful increases in complete abstinence rates over 6-month follow-up, with abstinence rates differing to controls by 10-21%.

It is also interesting to note that individuals in both the frequent call and text groups reported greater confidence to achieve their drinking goal of abstinence at 6-month follow-up compared to controls. This could have been a function of the contact they had with their therapist from residential treatment, or it may have been influenced by lower sustained abstinence rates in the control group over the 6-month follow-up period (at least compared to those in the monthly call group). As these outcomes were all measured over the same 6-month period, we cannot distinguish these two possibilities. In other words, the fact more control participants had recurrence of drinking or alcohol use disorder symptoms may have also resulted in lower confidence about remaining abstinent at 6-month follow-up.

Notably, groups were not different in terms of recovery capital related outcomes like employment, relationship, and residential situation, suggesting clinician driven phone check-ins don’t help in this domain. More targeted approaches to enhancing recovery capital, such as peer-led interventions and/or engagement with recovery community centers may be beneficial in this regard.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Though all participants had a drinking goal of abstinence at study baseline, the authors did not subsequently check for drinking goal. Given many individuals change their drinking goals following addiction treatment, this would have been good to check, and potentially statistically control for.

- We can’t know from these data what the longer-term benefits of regular check-ins might be, though other studies suggest lasting benefit.

Also, as noted by authors:

- Although patients were randomly assigned to one of the three intervention groups or the control group, neither the psychotherapist nor the patients were blinded.

- The control group did not meet all the criteria of a “true” control condition, because all study participants had the opportunity to contact the psychotherapist at any time if they needed support, and all participants knew that they would be contacted by phone and mail at 6-month follow-up.

- Data on abstinence and relapse, time to first drink, and additional continuing care were based on self-reports. This could have led to reporting bias especially given participants may not have wanted to disappoint their treatment provider who conducted the follow-ups.

- Only patients with alcohol use disorder and a drinking goal of abstinence or conditional abstinence for at least 6 months were included, which reduces the generalizability of the findings on patients with other drinking goals or other substance use disorders.

BOTTOM LINE

A 30 minute check-in call delivered approximately every 3-4 weeks post residential treatment discharge via telephone and using a cognitive-behavioral approach by psychotherapists from patients’ residential treatment program improves 6-month post-treatment alcohol use outcomes. This high-frequency contact might help individuals stay connected to health services and actively manage relapse risks.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study and others like it demonstrate clear benefits associated with ongoing recovery support services for individuals seeking recovery from addiction. Even though not all residential treatment programs offer ongoing recovery support services like in this study, maintaining some form of clinical care (e.g., individual therapy, attending groups) and/or engaging with community-based recovery supports like mutual-help meetings and recovery community centers can have tremendous benefits in terms of helping individuals sustain addiction remission and improve their well-being.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems:This study and others like it demonstrate clear benefits associated with ongoing recovery support services for individuals seeking recovery from addiction. Making phone check-ins a standard part of patients’ continuing addiction care following discharge from residential treatment will likely have a major positive impact on patient treatment outcomes.

- For scientists: This study and others like it demonstrate clear benefits associated with ongoing recovery support services for individuals seeking recovery from addiction. However, more work is needed explicating both the longer-term benefits of recovery management check-ins and their mechanisms of action and moderators of benefit.

- For policy makers: There is clear evidence supporting the benefits associated with ongoing recovery support services for individuals seeking recovery from addiction. Though such check-ins may represent an added cost to health-care systems up front, the greater benefits to individuals, public health, and long-term cost savings are shown in other research to be substantial. Supporting initiatives that promote continuing care for individuals in addiction recovery benefits everyone.

CITATIONS

Graser, Y., Stutz, S., Rösner, S., Moggi, F., & Soravia, L. M. (2021). Telephone- and text message-based continuing care after residential treatment for alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical multicenter study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(1), 224-233. DOI: 10.1111/acer.14499