Experiences among people who use drugs highlight mistreatment and stigma in the healthcare system

Stigma may be a barrier to accessing healthcare for people who use drugs, leading them to forgo or delay necessary medical care. Recently, educational interventions have targeted stigmatizing and negative views of healthcare providers toward people who use drugs, though some research suggests that these views have persisted. In this study, researchers characterized the healthcare experiences of people who use drugs in one county in Arizona utilizing an approach that involved community researchers with lived experience. Findings from this study could inform interventions to improve medical interactions for people who use drugs.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Most individuals in the United States with a drug use disorder do not seek treatment. Part of this treatment gap may be explained by the perceived stigmatization of people who use drugs, which may cause this population to forgo or delay necessary medical care. In fact, people who use drugs often cite mistreatment and stigma in medical settings. These experiences among people who use drugs are consistent with an extensive literature showing that negative attitudes of healthcare providers towards people who use drugs are common and contribute to suboptimal health outcomes for these individuals. Training for providers that addresses this stigma has increased in recent years, although some research suggests that negative attitudes toward people who use drugs are still pervasive among healthcare providers. One recent study, for example, showed that 75% of primary care physicians surveyed reported high levels of stigma towards individuals with opioid use disorder, on par with stigma toward these individuals in the general population.

In this study, researchers aimed to characterize healthcare experiences among people who use drugs in Maricopa County, Arizona, which includes the city of Phoenix. Of note, the research team included individuals with lived current and former drug use experience to help design and carry out the study, an approach called community-based participatory research. It was hoped that this study could help advance our understanding of the mistreatment of people who use drugs in healthcare settings. This better understanding could lead to policies and interventions that will improve medical interactions for people who use drugs and ultimately enhance health outcomes among this population.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was cross-sectional (i.e., done at one point in time) and used a 20-item survey designed for people who use drugs to characterize healthcare experiences among this population in Maricopa County, Arizona. The survey used quantitative (e.g., close-ended questions with pre-defined answers) and qualitative (e.g., open-ended questions) items and was administered by community researchers who had lived experience.

This study used a community-based participatory approach. Community members with lived experience who were part of the local drug users’ union were trained to become “community researchers” and were involved in recruiting study participants, designing and administering the survey, and interpreting the results. Drug user unions include members that are active drug users who work together to promote or oppose polices that affect people who use drugs, share knowledge around strategies to remain safe and healthy, and confront and combat stigma.

The study used a convenience sample where participants were recruited by community researchers in places frequented by people who use drugs. Recruitment was also done using social referrals from current study participants (known as snowball sampling). Survey eligibility included identifying as a person who uses drugs, being 18 years of age or older, and living in Maricopa County, Arizona. Surveys were administered between October and November 2019, and a financial incentive of $10 was offered for completion of the survey.

The 20-item survey included quantitative and qualitative items intended to measure service experiences. The focus on this particular study was on healthcare experiences and focused on those that sought medical care in the past year. The approach to characterizing healthcare experiences included asking whether or not people sought healthcare in the past year, asking about reasons for not seeking medical care if answered no, and exploring experiences with healthcare providers if answered yes. Healthcare providers refers to doctors, nurses, administrative staff, and other healthcare professionals that participants were exposed to during their healthcare-seeking experience.

Of the 185 participants that were surveyed, the majority of the sample (73%) reported drug use the day of or before the survey, 78% reported a history of injection drug use with more than half of this group indicating injecting drugs the day of the survey, just over half identified as male (59%) and white non-Hispanic (55%), and 29% reported unstable housing in the past year.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Many did not seek medical care in the past year.

Among the 185 participants surveyed, 40% reported that they did not seek medical care in the past year, with 34% of these individuals reporting that they did not seek needed healthcare because they were afraid of being mistreated by providers for using drugs.

Most individuals who sought medical care in the past year did not do so at a doctor’s office.

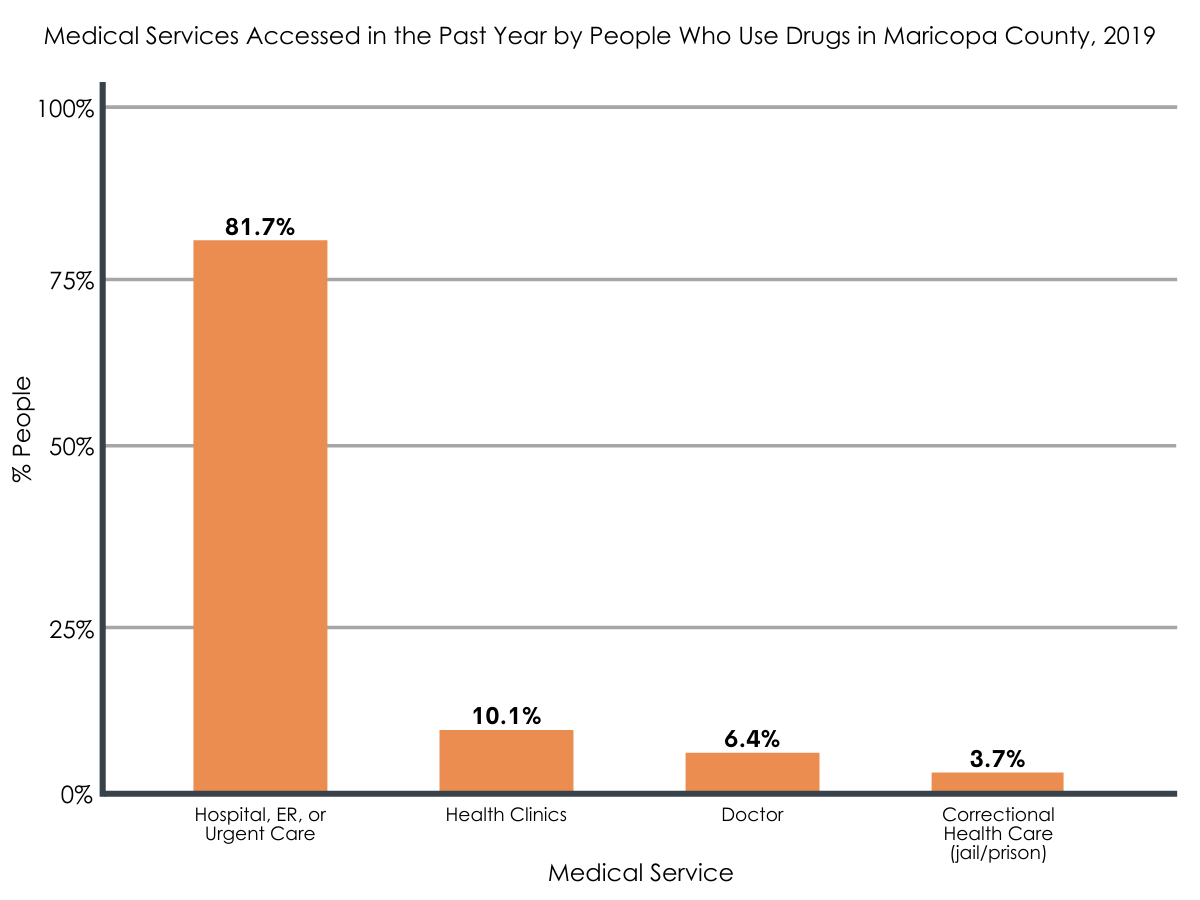

Among the 109 participants (59%) who reported seeking medical care in the past year, a large majority (82%) sought care in an emergency department, urgent care center, or a hospital. Only 10% sought care in a health clinic and 6% sought care at a doctor’s office.

Almost all participants seeking care reported medical maltreatment by healthcare providers.

Many participants reported that healthcare providers minimized or did not address their primary medical complaint. Instead, their drug use became the primary or sole focus of the medical visit even though none of the participants sought medical care for this reason. There were also reports of inappropriate or inadequate medical care, such as lack of pain management during painful procedures, and participants reported that they felt like the healthcare providers were “teaching them a lesson” or punishing them for using drugs.

Participants reported that healthcare providers expressed social disapproval of their drug use.

This social disapproval was both explicit and implicit though participants noted that it was always clear to them. Many participants perceived an immediate shift in the attitudes and behaviors of healthcare providers after learning of their current or past drug use or their use of medications for opioid use disorder treatment. There were several participants who reported that healthcare providers did not listen to them, were talking down to them, or treated them like a child.

Some participants reported emotional, verbal, or physical abuse by healthcare providers.

Several participants reported inappropriate medical care, such as unnecessarily painful procedures, that was designed to teach a lesson or make a point. Verbal abuse was typically expressed by lecturing the participant about their drug use.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The findings of this study suggest that among this sample of individuals who use drugs in Maricopa County, Arizona, many did not seek necessary medical care due to fear of mistreatment. Of those who did seek medical care in the past year, perceived mistreatment was common and included minimizing or not addressing their primary medical complaint, explicit and implicit social disapproval of their drug use, and verbal or physical abuse.

This study used a community-based participatory approach and was framed to highlight healthcare experiences among people who use drugs with a focus on experiences and expressions of stigma. Therefore, it is likely that findings will be biased towards negative experiences. However, this does not negate the fact that these experiences were common among the study participants and are likely to serve as barriers for seeking future medical care.

Integration of addiction services into the healthcare system has emerged as a way to identify and link individuals with substance use disorders to evidence-based treatment. These initiatives have been implemented for emergency department visits and inpatient hospitalizations, and have been augmented with peer recovery coaches.

Although these innovative program models have shown promise in identifying and linking individuals to treatment, there may be the unintended consequence of healthcare providers neglecting the primary medical complaints of people who use drugs in order to focus on screening and referral for substance use treatment. Findings from this study suggest that an individual’s drug use became the primary, and sometimes exclusive, lens through which healthcare providers interpreted the medical needs of the patient.

Not all people who use drugs have a substance use disorder and not all people who have a substance use disorder are interested in treatment. Building patient-provider relationships may be a better next step for improving health outcomes among people who use drugs. Indeed, it has been shown that people who use drugs who have a trusted medical provider have better health outcomes. However, only 10% of study participants sought care in health clinics and only 6% sought care at doctor’s office, the most likely settings to build a patient-provider relationship. Therefore, facilitating regular access to primary care services for people who use drugs is promising. One innovative primary care facilitation strategy may operate through clinics that are co-located with harm reduction services, such as syringe service programs.

One implication of this study’s findings is the importance of reassessing the role of educational interventions for healthcare providers in addressing negative attitudes and social constructions of drug use and people who use drugs. One review of the literature suggests that, although educational interventions alone can be useful in changing negative attitudes, contact-based approaches using individuals with lived experience can enhance and sustain these changes.

Stigma reduction interventions that use a positive empathy approach have also shown promise among healthcare providers. It is likely that interventions that go beyond didactics for healthcare providers are needed to address mistreatment of people who use drugs in medical settings. For providers that are interested in helping facilitate linkages to treatment for individuals with substance use disorder, training in empirically-supported, patient-centered approaches may help reduce patients’ perceived stigma. Such approaches allow providers to attend to the patients’ primary concerns, while also offering opportunities to discuss their drug use for those patients who are willing. Alternatively, other approaches that may be considered are policy interventions that create social and practice environments that prohibit or disincentivize mistreatment of people who use drugs. These may include medical malpractice reform, tying reimbursements to a quality metric that is specific to people who use drugs, and publicly reported healthcare performance related to this population. In general, stigma is complex, consists of many levels, and can manifest itself in many ways, so addressing it is not straightforward. We are still learning about the many dimensions of the stigma construct as it relates to people who use drugs and how interventions might be designed to reduce it. Studies like this one help in these endeavors.

One simple, empirically-supported way to reduce stigma in healthcare settings is to change the language used to describe people who use drugs and addiction. Original experimental research from the RRI has shown that, among the general population and specifically among mental health clinicians, using the term ‘substance abuser’ compared with the person-first term ‘person with a substance use disorder’ increases stigma. Language plays an important role in framing how society thinks about substance use and recovery. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary®.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Although also a strength, the use of community researchers and the a priori framing of the survey to highlight negative healthcare experiences of people who use drugs likely led to biased perspectives that did not include positive experiences that have been reported in other studies.

- This study had a small sample size though it was likely adequate in providing meaningful qualitative findings from the survey.

- The study took place in one county in Arizona, which is an area known for a criminal justice approach to people who use drugs. Thus, generalizability of these findings to the entire United States or other cities and states in the country is limited.

- The study was missing key variables, such as type of substance used, the presence of injection drug use, the type of healthcare provider, or the healthcare setting, to contextualize the interaction between healthcare providers and people who use drugs.

BOTTOM LINE

This study surveyed people who use drugs to characterize their healthcare experiences. Findings suggest that many people who use drugs in one area of the United States did not seek necessary medical care due to fear of mistreatment and, of those who did seek medical care in the past year, perceived mistreatment was common and included minimizing or not addressing their primary medical complaint, explicit and implicit social disapproval of their drug use, and verbal and physical abuse.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Mistreatment of people who use drugs in medical settings is documented and oftentimes is the byproduct of negative attitudes and social constructions of drug use and people who use drugs held by some healthcare providers. Very few people who use drugs have a trusted relationship with a healthcare provider, which can be cultivated through ongoing medical care received in a health clinic or a doctor’s office. This may be the best avenue to ensure appropriate and quality medical care for people who use drugs.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Many of the study participants did not seek necessary medical care for fear of mistreatment. In addition, most who sought medical care experienced mistreatment, which is likely to negatively impact necessary healthcare-seeking in the future. Studies suggest that the negative attitudes and social constructions of drug use among many healthcare providers are contributing to this mistreatment. High levels of stigma still exist in the healthcare system and interventions are needed to reduce it. These may go beyond didactics and include academic detailing using people with lived experience, positive empathy approaches, and structural changes. In addition, language plays an important role in framing how society thinks about substance use and recovery. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary®.

- For scientists: Stigma is complex and multifaceted so addressing it is not straightforward. We are still learning about the many dimensions of the stigma construct as it relates to people who use drugs and how interventions might be designed to reduce it. This study focused on perceived stigma among individuals who use drugs in a county known for a criminal justice approach to addressing substance use. Future studies could add to critical contributions like these by examining how an individual’s primary drug of choice affects mistreatment in medical settings, if current injection drug use is related to higher levels of mistreatment, and if certain types of healthcare professionals or medical settings exhibit higher levels of mistreatment and stigma. Additionally, as this area of the United States is known to take a criminal justice approach to people who use drugs, future studies that account for the larger political and sociocultural influence for a given sample when examining mistreatment of people who use drugs would be interesting and potentially useful.

- For policy makers: Findings from this study show that perceived mistreatment of people who use drugs is common in this healthcare system. Many of these individuals suffer from substance use disorders, a medical condition, and others are subject to the negative attitudes on drug use among healthcare providers. There may be approaches to reduce the mistreatment of people who use drugs in addition to trainings addressing stigma among healthcare providers, such as policy interventions that create social and practice environments that prohibit or disincentivize mistreatment of people who use drugs. These may include medical malpractice reform, tying reimbursements to a quality metric that is specific to people who use drugs, and publicly reported healthcare performance related to this population.

CITATIONS

Meyerson, B.E., Russell, D.M., Kichler, M., Atkin, T., Fox, G., Coles, H.B. (2021). I don’t even want to go to the doctor when I get sick now: Healthcare experiences and discrimination reported by people who use drugs, Arizona 2019. International Journal of Drug Policy, 93, 103112. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103112