Disparities in the overdose crisis? A comparison of Black and White communities in America

In light of the escalating opioid crisis, understanding how racial-ethnic groups may be differentially affected is key to tailoring support and services. This study compared overdose death rates between Black and White Americans across time from 1999 to 2018.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The United States (US) has been battling an increasingly worsening opioid-related overdose crisis for the past two decades. Though death rates are currently at record highs, population-level overdose rates dropped slightly between 2017 and 2018 just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, giving communities and public health experts hope we had turned a corner in the crisis. However, given Whites in the United States have historically higher rates of opioid use and comprise the majority of the population in all 48 contiguous US states, reductions in opioid-involved overdose deaths only among Whites were found to be driving the observed changes between 2017 and 2018. While deaths among Whites decreased during this period, opioid overdose deaths among Black and Hispanic Americans increased, leading the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to publish a special report highlighting this alarming trend.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the opioid overdose crisis started with widespread prescribing of opioids in the 1990s and, through 2018, included three waves of opioid-involved overdose deaths. The first CDC-defined wave of opioid overdose deaths was from 1999 to 2010 and was primarily driven by natural and semi-synthetic opioids and methadone. The second wave began in 2010, with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin. The third wave started in 2013 as a result of synthetic opioids, including illicitly manufactured fentanyl, which has particularly high potential to cause overdose.

It is unclear however, if these crisis waves characterize trends for all racial groups in the US, or if they are a product of over-representation of Whites in the population, and/or health disparities that adversely affect medical and psychological care for racial-ethnic minorities. In this study, the researchers compared differences in rates of opioid-involved overdose deaths in the US from 1999 to 2018 between African Americans and Whites.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was an observational study of national and state-level epidemiological data on overdose death rates in the US done to assess potential similarities and differences in opioid overdose deaths between African Americans* and Whites from 1999 to 2018.

* National US Government epidemiological statistics use the racial category ‘African American’, but many people in the US who identify as Black do not identify as African American, meaning these data may not fully represent Black people in America.

Age-adjusted opioid overdose death rates from 1999 to 2018 were obtained from the CDC Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER). The multiple cause of death data in the CDC WONDER combines county-level death data from a given calendar year obtained from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), and population-level data obtained from the US Census to produce death rates by year.

First, the researchers calculated the relative change in opioid overdose death rates by race at the national and state levels from 1999 to 2018. The researchers also assessed relative change in opioid overdose death rates over three fixed time-periods: 1999–2010 (wave 1), 2010–2013 (wave 2) and 2013–2018 (wave 3), in line with the CDC-defined three waves of the opioid overdose crisis.

For state-level data, because the CDC WONDER considers death counts less than 20 per year unreliable for statistical analysis, the researchers only included data in their state-level analyses where states reported greater than 20 opioid related deaths per year during each year of the CDC-defined opioid crisis waves. In wave 1, there were 10 states with greater than 20 deaths for African Americans and Whites for every year from 1999 to 2010; during waves 2 and 3, there were an additional 11 states with greater than 20 deaths for African Americans and Whites in every individual year.

Next, the authors used the Joinpoint Regression Program from the National Cancer Institute to examine national opioid overdose death trends. This software allows researchers to study trends in phenomena across distinct time periods and identify transitional points when a phenomena significantly increased or decreased in prevalence.

Finally, the researchers compared opioid overdose death rates between African Americans and Whites across the three CDC-defined opioid overdose death waves to understand how trends like changes in opioid availability differentially impacted African Americans and Whites.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Throughout the opioid overdose crisis, death rates have generally worsened, but not at the same rates for African Americans and Whites.

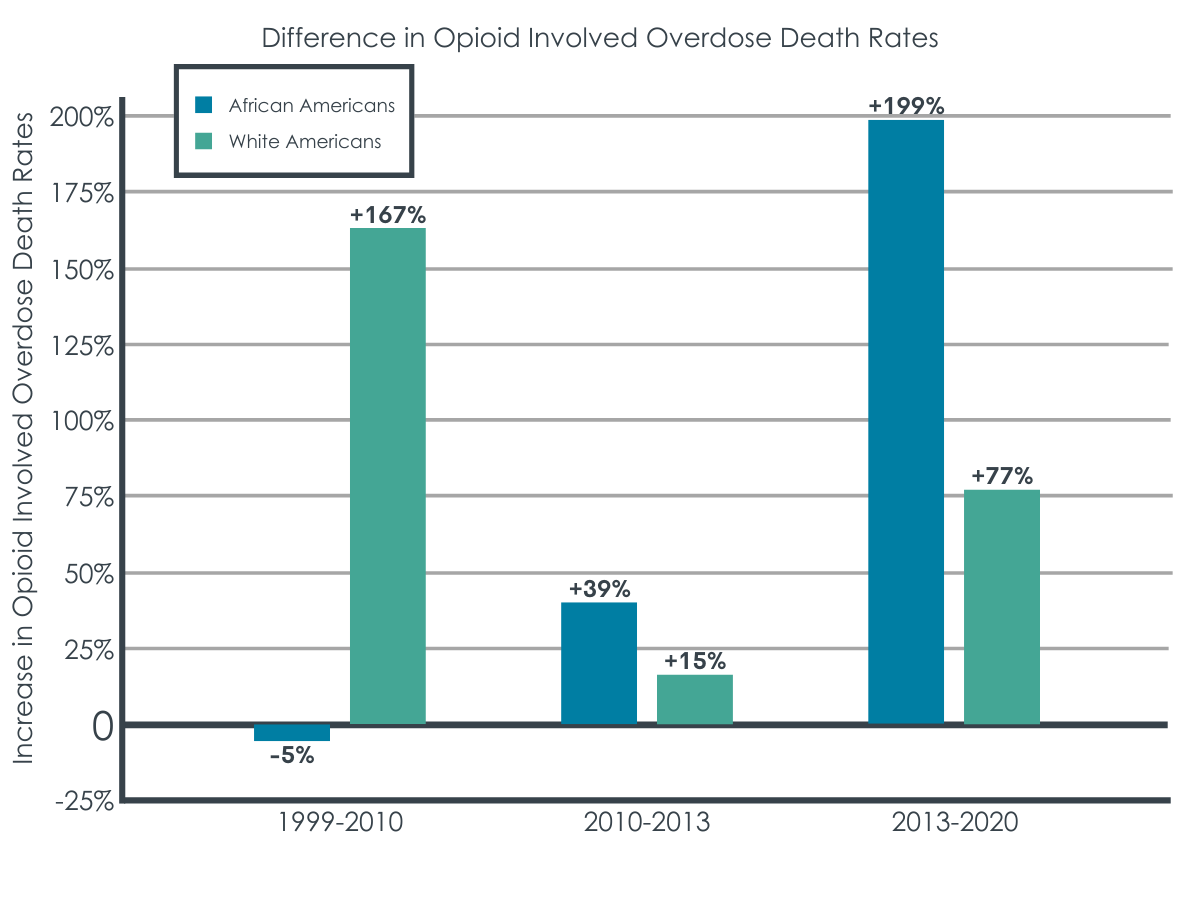

Nationally, during wave 1 (1999–2010), there was a 167.2% increase in opioid related deaths among Whites, while there was 5.5% reduction for African Americans. In wave 2 (2010–2013), death rates continued to increase among both Whites and African Americans, however, deaths increased more among African Americans during this period (39.0% versus 15.8%). Most recently, in wave 3 (2013–2018), deaths among African Americans increased 198.7% versus 77.0% among Whites.

At the state‐level, African Americans had a lower relative change in opioid overdose death rates compared to Whites in all 10 states included in wave 1 analysis (1999–2010). During wave 2 (2010–2013), African Americans had a higher relative change compared to Whites in 52% of the included states. In wave 3 (2013–2018), African Americans had a higher relative increase in opioid overdose death rates in all included states.

In terms of annual percentage of change in opioid overdose death, as the picture improved for Whites in the late 2010s, things got worse for African Americans.

The joinpoint regression analysis indicated no major change in opioid overdose death rate for African Americans from 1999 to 2012, even though there were observed increases in absolute opioid overdose deaths among this group (0.5% annual increase). However, from 2012 to 2018, the opioid overdose death rate for African Americans increased, with a calculated annual percentage increase of 26.2%.

For Whites, three notable shifts in opioid overdose deaths rates were found: 2006, 2013 and 2016. From 1999 to 2006, the annual percent of change increased 12.4%, while from 2006 to 2013 the annual percent of change decreased to 4.3%. Death rates however, substantially increased again by 19.0% annually from 2013 to 2016. Most recently, for Whites, from 2016 to 2018 there’s been a sharp but non-statistically significant annual decrease of 5.1% in opioid overdose death rates.

Average annual percentage change in opioid overdose death during crisis periods shows a growing disparity between African Americans and Whites.

Nationally, during wave 1 of the opioid overdose crisis (1999–2010), the average annual percentage change in opioid overdose deaths was lower among African Americans compared to Whites (0.5% versus 9.4%). In contrast, the average annual percentage change for opioid overdose deaths increased for both groups but was higher among African Americans than whites during wave 2 of the crisis (8.4% versus 4.3%), and the disparity increased even further during wave 3 (26.2% versus 13.2%).

At the state level, in wave 1, African Americans had a smaller average annual percentage change compared to Whites in eight of the 10 states studied. In wave 2, 11 of 21 states had a higher average annual percentage change in opioid overdose death for African Americans compared to Whites. During wave 3, the racial disparity persisted in nine of the 11 states from wave 2 and increased by an additional four states, leading to a higher average annual percentage change in opioid overdose deaths in African Americans compared with Whites in 13 of 21 states (61.9%).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

While Whites in the US have a higher overall prevalence of opioid involved overdose deaths, this is in large part because Whites make up a greater portion of the US population. And while opioid involved overdose deaths continue to rise for both Blacks and Whites, the change in the rate of opioid involved overdose deaths is increasing more rapidly among African Americans. The researchers’ results highlight a critical need to attend to equity in opioid overdose prevention, intervention and treatment resources, as well as targeting efforts in states with demonstrated disparities in opioid involved overdose deaths.

The authors of this paper recommended the expansion of the US Department of Health and Human Services’ strategy for managing the opioid overdose crisis by explicitly including ongoing examination of racial disparities in opioid involved overdose deaths, by race analysis of medical and public health prevention and intervention data and equity‐driven policy interventions to ensure that African Americans are not being marginalized in the fight against opioid misuse. In other words, it will be important to discover exactly why there has been such a dramatic increase in overdose deaths among Black Americans so that these can be properly and urgently attended to.

In general, it has been suggested that to address health disparities between Black and White Americans, one must first address structural disparities like differing access to employment and housing. And while the US has shifted toward more effective and less punitive approaches for managing opioid use, racial inequities in drug enforcement remain, through both the disproportionately harsh treatment of Black Americans by the criminal justice system for opioid‐related offenses and inequitable access to treatment. While these inequities have always existed, it’s possible that the recent shift towards treating rather than punishing people with opioid use disorder, and increased access to opioid use disorder care is disproportionally benefitting White Americans. In other words, these shifts in public and healthcare policy may be more successfully mitigating opioid overdoses among White Americans, relative to Black Americans.

As noted by the researchers, public policy must recognize the different treatment of Black versus White Americans in its approach, and think about these differences when developing public health initiatives.

As is typical in these kinds of studies, current or past year data is often not yet available to researchers at the time of publication. As such, this paper does not report on the COVID-19 pandemic period from 2019 to 2022, with most recent data showing an annual increase to 107,000 overdose deaths in 2021. However, based on other research showing health disparities between Black and White Americans were amplified by COVID-19, it is likely this trend has continued. It is also unclear how the predicted fourth wave of opioid overdose deaths that is projected to involved stimulants (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines) in combination with fentanyl will differentially affect Black and White Americans.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the authors:

- While National Vital Statistics System provides the best and most complete data to monitor trends in opioid involved overdose deaths, these data rely on death certificates that are completed by coroners or medical examiners. Given differences in medical training between medical examiners and coroners (less likely to be physicians), there may be varying levels of missingness on death certificates regarding specificity of drugs involved in overdoses.

- Death certificates with unspecified drug poisoning deaths probably lead to an underestimate of opioid involved overdose deaths.

- The joinpoint regression approach does not allow for state‐level clustering of opioid involved overdose deaths or inclusion of covariates, which makes it difficult to tease out additional factors that may be influencing racial differences in opioid involved deaths. This is a weakness compared to more conventional regression approaches. At the same time, the joinpoint model allows for quantitative identification of time‐points where there are changes to the trend, which is a benefit not offered by conventional forms of regression.

Additionally:

- National US Government epidemiological statistics use the racial category ‘African American’, but many people in the US who identify as Black do not identify as African American, meaning these data may not fully represent Black people in America.

- As is typical in these kinds of studies, current or past year data is often not available to researchers conducting this research. It is probable that at the time of preparation of this paper, the most recent data available to the researchers was 2018. As such, this paper does not report on the COVID-19 pandemic period from 2019-2022, which likely showed an amplification of disparities between African Americans and Whites.

BOTTOM LINE

While the opioid crisis initially affected Whites in the US at higher rates, the acceleration of opioid‐involved overdose deaths for African Americans, as of 2018, outpaces that of Whites and signals a growing disparity, which has likely only increased more during the COVID-19 pandemic. Research is needed to identify the exact nature of the causes of such growing disparities along racial/ethnic lines in order these can be properly addressed. More generally, public health policies are urgently needed that can address the ongoing opioid overdose crisis in ways that consider how White and Black Americans may be differentially benefitting from recent changes in public and healthcare policy designed to address the ongoing opioid overdose crisis.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Opioid involved overdoses are at an all-time high in the US, with deaths among Black Americans growing at a faster rate than Whites. Though not yet prevalent in the US, supervised drug consumption sites dramatically decrease the likelihood of fatal opioid overdose among those who engage with them. These sites typically also offer recovery support services for when people are ready to engage with treatment. Also, carrying naloxone (best known by the brand name Narcan), which can reverse the effects of opioid overdose, saves lives. A standing prescription for this medication is in place in most pharmacies in America, allowing anyone to buy this medication over the counter.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Opioid involved overdoses are at an all-time high in the US, with deaths among Black Americans growing at a faster rate than Whites. It is critical treatment providers and treatment systems “meet patients where they’re at”, and if they’re not ready to engage with treatment or abstain from drug use, to help individuals connect with harm reduction services like supervised drug consumption sites which dramatically decrease the likelihood of fatal opioid overdose, and needle exchange programs that reduce the transmission of diseases like HIV AIDS and hepatitis C.

- For scientists: The opioid overdose crisis remains one of the most important and vexing public health problems of our time. Research is urgently needed to bring to light the psychosocial determinants of the growing disparity in overdose death rates between Black and White Americans. Work is also urgently needed developing culturally sensitive interventions that can reduce harms associated with opioid use in Black communities in the US. Also, more work is needed on strategies that link individuals to treatment, and recovery and harm reduction services after an overdose.

- For policy makers: While many public health policies in the US have begun to address the opioid overdose crisis, these policies likely benefit Whites more than Blacks, for whom numerous forms of disparities confer additional risk (e.g., poorer access to housing, employment, and healthcare). These findings highlight the need to apply a health equity lens to public health initiatives so that all racial groups can benefit from these initiatives. Harm reduction policies like needle exchanges and supervised drug consumption sites have been shown to dramatically reduce opioid death rates and the spread of transmissible diseases like HIV AIDS and hepatitis C. Increasing access to such harm reduction resources will have major public health benefit. Also, supporting research and implementation of services that link individuals to treatment and recovery support services after an overdose will ultimately lead to improved public health.

CITATIONS

Furr-Holden, D., Milam, A. J., Wang, L., & Sadler, R. (2021). African Americans now outpace whites in opioid-involved overdose deaths: A comparison of temporal trends from 1999 to 2018. Addiction, 116(3), 677-683. doi: 10.1111/add.15233