Therapy related to improved buprenorphine treatment retention

Medications for opioid use disorder are highly effective, yet are often discontinued prematurely. In a very large sample of adults with Medicaid insurance, researchers examined if psychosocial and behavioral therapy helped retain adults with opioid use disorder in buprenorphine treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Agonist medications for opioid use disorder, like buprenorphine, are among the most effective interventions for addressing it. However, it is common for patients starting buprenorphine to discontinue the medication before reaching the recommended 6-month duration of treatment to achieve reduced overdose risk. Research can help identify factors that predict buprenorphine treatment retention or discontinuation in order to develop and test strategies to improve buprenorphine retention.

Clinical guidelines and expert recommendations suggest psychosocial and behavioral therapy (hereafter referred to as “therapy”) is important for engagement and retention in treatment for opioid use disorder, however current scientific literature is mixed – some studies suggest therapy in conjunction with medication for opioid use disorder improves patient health outcomes, while other studies suggest there are no added benefits.

In this study, researchers used Medicaid claims data to understand how therapy in conjunction with medication for opioid use disorder affects retention or discontinuation of medication treatment over time. Using Medicaid data is innovative because Medicaid is the largest insurance provider for Americans with lower-incomes and covers the largest share of addiction treatment costs in the U.S. This allows the researchers to examine a very large sample of individuals receiving treatment for opioid use disorder over time.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The researchers retrospectively examined a cohort of (N = 61,976) adults who initiated buprenorphine treatment from 2013 – 2018. Participant’s Medicaid claims data for the first 6 months in buprenorphine treatment were used to examine the relationship between therapy participation and buprenorphine discontinuation.

Participants were included in this study if they were between the ages of 18-64 and had been prescribed buprenorphine for at least 7 consecutive days and had not received any buprenorphine prescriptions or opioid use disorder-related therapy in the previous 6 months. The researchers excluded buprenorphine episodes less than 7 days in duration because those could represent detoxification sessions rather than maintenance treatment. They also excluded individuals with any opioid use disorder-related therapy services during the previous 6-month baseline period prior to initiating buprenorphine to capture new therapeutic episodes.

Therapy services included individual, group, and family psychotherapy or counseling services connected to an opioid use disorder service claim to capture treatment episodes specifically focused on opioid addiction. However, opioid use disorder did not have to be the primary diagnosis, which may include other psychiatric disorders (e.g., other substance use disorders, depression, anxiety).

The researchers also recorded participants’ demographic information, pre-treatment clinical histories, and health service use from their Medicaid enrollment and claims data. Demographic information included sex, age, race/ethnicity, and insurance plan type (capitation or fee-for-service plan, which differs by state policy). Participants’ pre-treatment medical and mental health co-morbidities, opioid and other substance use disorders, and health service use were recorded based on Medicaid claims submitted during the baseline period and cross-checking the data with common insurance coding systems used in the U.S.

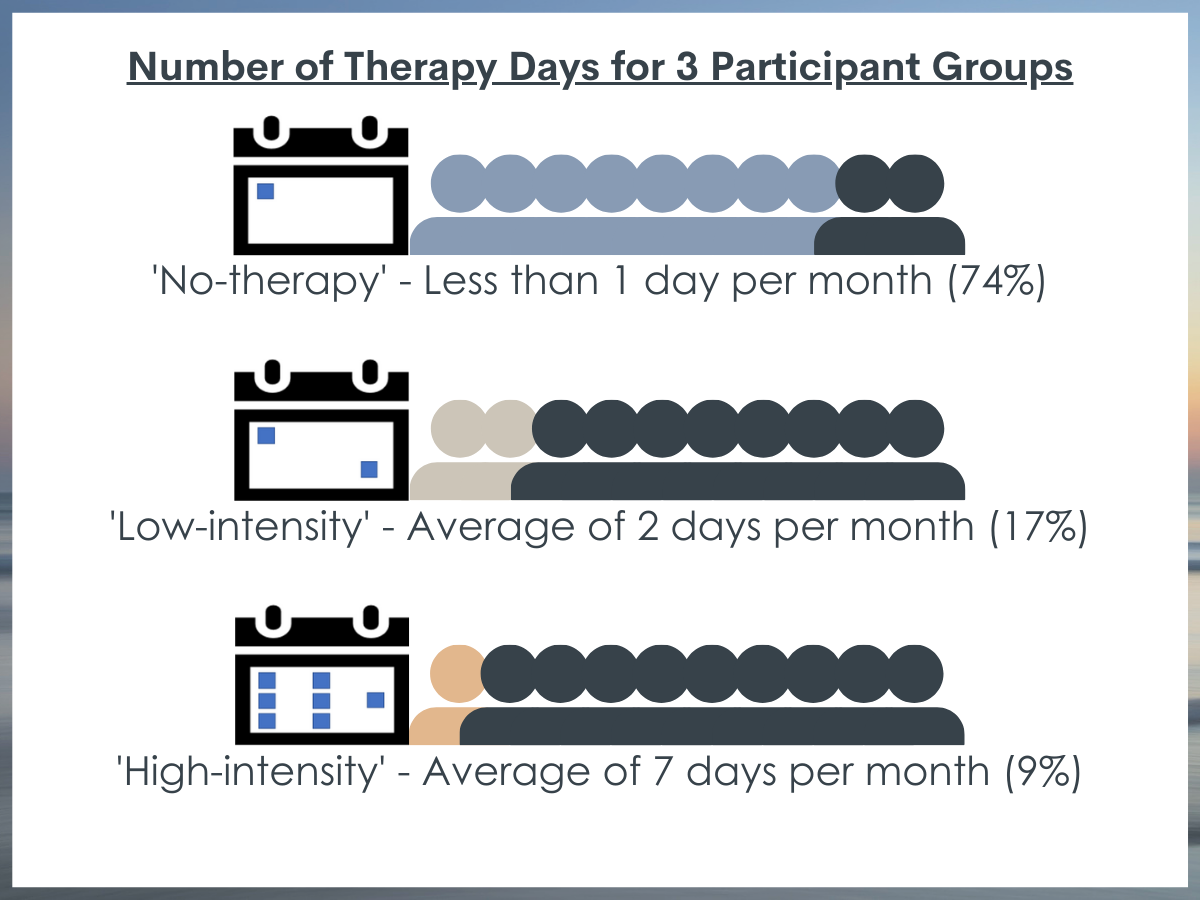

First, the researchers used a statistical technique to identify groups of participants with similar patterns or trajectories of opioid use disorder-related therapy services in the first 6 months after starting buprenorphine treatment. The researchers found three treatment trajectories they called no therapy, low-intensity therapy, and high-intensity therapy.

Second, the researchers ran statistical analyses to test if certain participant demographic and clinical characteristics (i.e., age, sex, race/ethnicity, Medicaid plan type, mental health diagnoses, substance use disorders, medical comorbidities, health services, and prescription drugs) were associated with each of the different therapy trajectories.

Third, controlling for demographic and clinical characteristics, the researchers calculated the probability or likelihood that buprenorphine discontinuation would occur for each group (low-intensity therapy or high-intensity therapy vs. no therapy). Statistical techniques that control for demographic and clinical differences across the three therapy groups helps the researchers to isolate the unique effect of psychosocial therapy on buprenorphine discontinuation. This technique helps to make a better case that therapy caused any observed differences in buprenorphine retention/discontinuation. The researchers ran additional analyses using different approaches to define variables called “sensitivity analyses” to see if they would observe the same results.

Participants in the ‘no therapy’ group had an average of less than 1 day per month of therapy services and was the largest proportion of the sample (74%). The ‘low-intensity’ therapy group had an average of 2 days per month of therapy services and composed about 1/5 of the sample (17%). The ‘high-intensity’ therapy group had an average of 7 days per month of therapy services and was the smallest proportion of the sample (9%). Overall, about 1/3 of the sample had 6 months (180 days) or longer of medication treatment (n = 21,578; 34.8%) and 2/3rds of those who achieved 180 days of medication treatment were in the group with no therapy (n = 14,591; 67.6%).

Participants were on average 35 years old, a majority White (90.5%) and non-Hispanic, and a little more than half male (60.2%). In terms of mental health diagnoses, about 20% of participants had depression and a quarter of participants had anxiety. In terms of documented substance use disorder diagnoses pre-treatment, a majority of the sample had opioid use disorder (no therapy 47.4%, low-intensity 68.1%, high-intensity 79.2%), and many had tobacco use disorder (no therapy 28.5%, low-intensity 27.4%, high-intensity 30.2%) or another drug use disorder (no therapy 16.9%, low-intensity 17.5%, high-intensity 23.1%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Individuals in the low-intensity and high-intensity therapy trajectories tended to have more severe clinical histories before treatment.

Compared to the no therapy group, participants in the low and high-intensity therapy trajectories were more likely to have capitated Medicaid plans, opioid use disorder pre-treatment, cannabis use disorder pre-treatment, use the emergency department, and have an opioid overdose history before starting buprenorphine treatment. The high-intensity therapy group had a larger proportion of participants with mental health diagnoses and substance use disorders across all substance categories pre-treatment than the low-intensity and no therapy groups, and were more likely to be prescribed antidepressant and antipsychotic medications.

Therapy was associated with medication treatment retention.

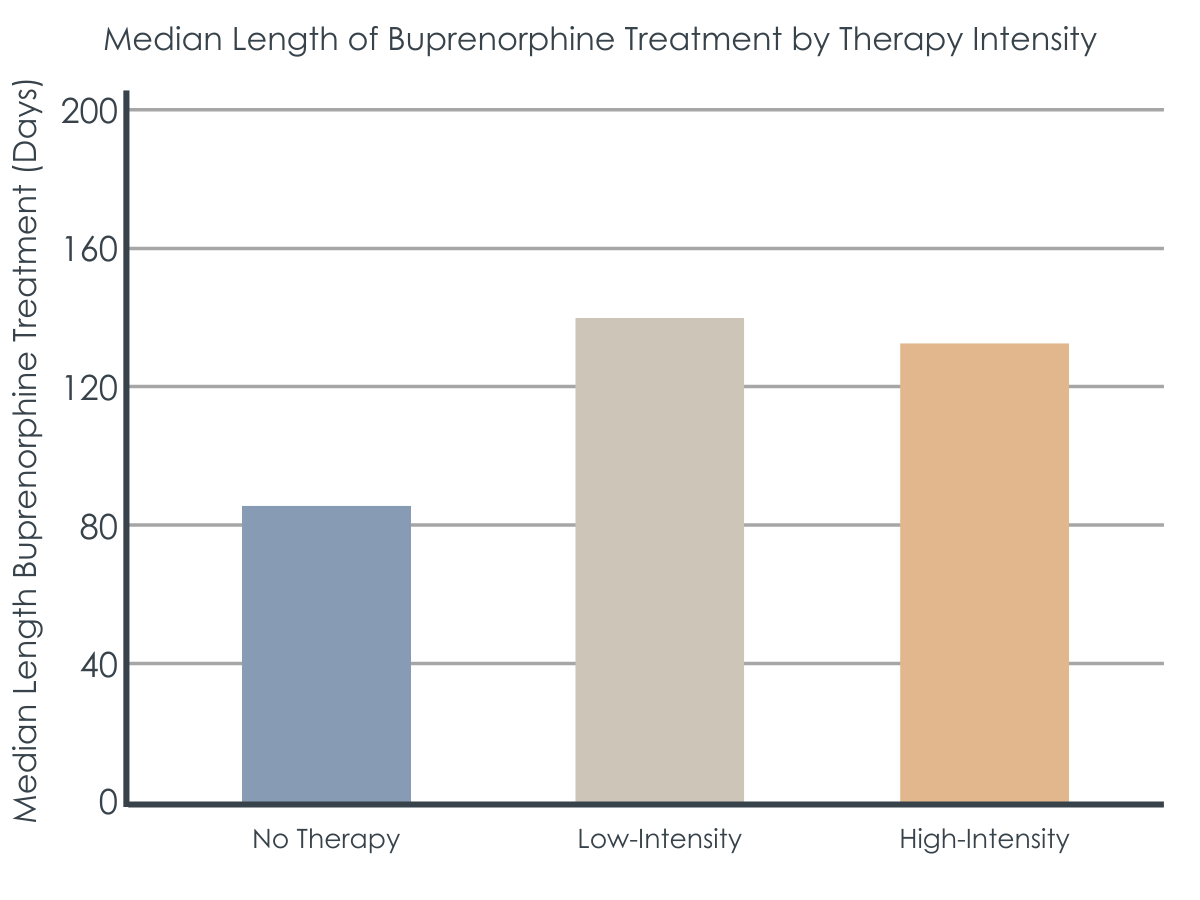

After equating groups statistically on a series of demographic and clinical variables, participants in the low-intensity therapy group were 45% less likely to discontinue buprenorphine in the first 6 months (180 days) compared to the no therapy group. Participants in the high-intensity therapy group were about 30% less likely to discontinue buprenorphine in the first 6 months (180 days) compared to the no therapy group.

In the no therapy group, the median length of buprenorphine treatment was 84 days, whereas the median length of medication treatment in the low-intensity group was 145 days, and 136 days in the high-intensity group. Similarly, a smaller proportion of participants in the no therapy group (31.9%) reached the 180-day benchmark, whereas 43.3% of participants in the low-intensity and 42.4% of participants in the high-intensity reached the 180-day benchmark for medication treatment duration.

The researchers looked at these analyses in a number of different ways and found the same pattern of results, even when they included participants without opioid use disorder pre-treatment and therapy services not connected to an opioid use disorder diagnosis.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study suggests that psychosocial and behavioral therapy (“talk therapies”) may help to reduce premature buprenorphine discontinuation and help to retain patients longer in buprenorphine treatment. Therapy services were associated with a reduced risk of buprenorphine discontinuation even when the researchers controlled for different service patterns, pre-treatment clinical characteristics, and examined therapy services continuously over time, regardless of overall therapy trajectories. This type of analytic approach helps make a stronger case that psychosocial and behavioral therapy may help address premature buprenorphine discontinuation.

Therapy may help do this in a number of ways, such as by providing regular clinical attention and care through regular check-ins on dosing and adherence to the medication regimen. This can, in turn, help to build and maintain motivation for ongoing treatment engagement, and can help to problem-solve barriers to engagement. That said, past randomized controlled research in this area has been mixed in showing that therapy actually adds any benefits to medication alone. For example, in one study comparing different types of therapy (contingency management, cognitive behavioral therapy) with medication for opioid use disorder, there were no differences in clinical outcomes between groups who received contingency management, cognitive behavioral therapy, both contingency management and cognitive behavioral therapy, or merely medication management check-ups (“medical management”) alone. It is notable in that study even the medical management group (which was considered a no therapy “control group”), participants still received a weekly visit with a physician to review urine analysis results, medication dosage, encouragement to attend recovery-focused mutual-help organizations, and adherence to the dosing schedule. Medical management, sometimes also called medication management, is often provided along with buprenorphine in rigorous randomized controlled trials of buprenorphine’s effectiveness. While slightly different depending on the study, these manualized and structured 30–45-minute check-ups for individuals receiving buprenorphine may well be more than what is offered in usual, busy, day to day clinical practice. Consequently, it may confer similarly helpful therapeutic components as those provided in more elaborate cognitive and behavioral interventions. Supporting this notion, in a review of 8 studies, researchers found that psychosocial treatment (i.e., contingency management) did have additional benefits on reducing opioid use during treatment when medical management was not as structured.

Past studies may be showing mixed results for a few reasons. Medication management manuals include encouragement to participate in recovery support services like mutual-help, which have also shown benefits for people in buprenorphine treatment, specifically increased abstinence (e.g., through increased Narcotics Anonymous participation). Also, cognitive behavioral therapy may not show any additional benefits when added to buprenorphine treatment because both treatments focus on addressing craving. However, cognitive behavioral therapy and other psychosocial treatments for other mental health conditions like depression and anxiety can help address many symptoms relevant to substance use disorder, such as increasing positive and rewarding substance free activities, and learning strategies to effectively manage symptoms of anxiety and depression that may be triggers for substance use. So, it is plausible that additional therapy may be especially beneficial for people experiencing co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders. Another reason why outcomes from prior studies show mixed results is because of their focus on different clinical variables, such as opioid use during treatment, whereas less research has focused on retention in treatment, like in the current study.

Surprisingly, whereas there was a measurable benefit on buprenorphine retention for any therapy vs no therapy, there was not a therapy “dose-response” effect in which more regular therapy related to greater decreased risks in buprenorphine discontinuation. This might be because the high-intensity therapy group had more severe clinical presentations and treatment courses (e.g., more likely to have an opioid overdose history), which might have offset the expected added benefit that might come from more therapy. Alternatively, there may be a certain therapy threshold that is sufficient to facilitate greater retention in buprenorphine treatments and, once such a threshold is met, additional therapy doesn’t add to it; it may add other kinds of therapeutic opioid use disorder recovery benefits, however, not reported in this study (e.g., greater relapse prevention coping skills).

Because this study was so large, it is more likely that these results may be generalizable to and representative of the population of people on Medicaid receiving medication for opioid use disorder. Additionally, the researchers use of advanced statistical techniques helps to examine the potential causal relationship between psychosocial and behavioral therapy and medication discontinuation in a naturalistic setting. Although the researchers were unable to report the specific types of therapy delivered, results suggest that psychosocial therapy generally may have a benefit on retaining patients longer in medication treatment for opioid use disorder. These results, however, cannot speak to requiring therapy as a condition for receiving buprenorphine. Rather, results suggest that providers might inform patients that some additional therapy may improve their overall treatment and recovery outcomes by increasing ongoing use of buprenorphine.

It is notable that 75% of the sample had no therapy during the 6-month period and that participants in this group were also more likely to be prescribed stimulants, benzodiazepines, and sedatives – medications commonly prescribed for ADHD, anxiety, and sleep problems. It is unclear whether participants in this large group were clinically recommended or referred to receive therapy and didn’t want to attend any sessions, or whether they were never clinically recommended to attend. If the latter is true, findings here suggest that providers might be missing opportunities to recommend therapy to these patients where they could learn psychosocial approaches to coping and enhanced well-being, without requiring therapy to receive buprenorphine. Additional therapy may help patients learn additional skills that may assist them in the longer term as they stabilize and perhaps decide to discontinue the use of medication.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The nature of Medicaid claims reporting prevented the researchers from being able to determine what types of psychosocial and behavioral therapy were provided, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or contingency management. Similarly, only services that generated a Medicaid claim were included in the study, so services patients received not covered by Medicaid, such as self-help, 12-step, or peer support, were not captured or reported. This limits the researchers’ ability to determine what specific types of therapy were most common or most effective for medication treatment retention.

- Participants in this study were only those covered by Medicaid. That means that findings from this study may not generalize to individuals with no insurance or private coverage.

BOTTOM LINE

This study found that, among 61,976 adults covered by Medicaid who initiated buprenorphine treatment in 2013-2018, receipt of some kind of additional psychosocial therapy (talk therapy) was associated with a reduced risk of premature medication discontinuation. Therapy, even at infrequent intervals (i.e., twice per month), may help retain some patients in medication treatment for opioid use disorder.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Medication for opioid use disorder, such as buprenorphine, is among the most effective treatments for opioid use disorder. Yet, many patients initiating medication for opioid use disorder discontinue before achieving the recommended 6-month minimum duration. Psychosocial and behavioral therapy was associated with greater retention on buprenorphine among patients who were starting buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. Some minimal level of psychosocial therapy (e.g., twice per month) may help patients stay engaged and motivated, problem solve barriers, and maintain appropriate medication dosing to ultimately achieve the goal of symptom remission.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder, such as buprenorphine, is among the most effective treatments for opioid use disorder. Yet, many patients initiating medication treatment discontinue before achieving the recommended 6-month minimum duration. Psychosocial and behavioral therapy was associated with helping to retain patients in treatment who were starting buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. In the current study, even 2 therapy sessions a month (every other week), reduced the risk of buprenorphine discontinuation by 45%. This suggests that even low-intensity therapy may help patients stay engaged and motivated, problem solve barriers, and maintain appropriate medication dosing to ultimately achieve the goal of symptom remission.

- For scientists: Findings from this large, longitudinal retrospective cohort study (N = 61,976) using Medicaid claims data from 2013-2018 showed that psychosocial and behavioral therapy was associated with a reduced risk of buprenorphine discontinuation in the first 6 months of treatment by 30-45%. Propensity score matching was used to control for the effect of different service patterns and pre-treatment clinical characteristics on medication discontinuation. Sensitivity analyses that included psychosocial and behavioral therapy not connected to an opioid use disorder diagnosis and examined therapy services continuously overtime, regardless of overall therapy trajectories, showed the same pattern of effects. Strengths of this study include its large sample size that increases generalizability and its robust statistical techniques that increase confidence in the association between therapy and medication discontinuation in a longitudinal, naturalistic setting. The researchers were unable to report the specific types therapy provided, given the nature of Medicaid claims data. Future research should examine the effects of specific therapy types on treatment retention in community settings.

- For policy makers: Pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder, such as buprenorphine, is among the most effective treatments for opioid use disorder. Yet, many patients initiating medication treatment discontinue before achieving the recommended 6-month minimum duration. Psychosocial and behavioral therapy was associated with helping to retain patients in treatment who were starting buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. In the current study, even 2 therapy sessions a month (every other week), reduced the risk of buprenorphine discontinuation by 45%. This suggests that even low-intensity therapy may help patients; perhaps helping them stay engaged and motivated, problem solve barriers, and maintain appropriate medication dosing to ultimately achieve the goal of symptom remission. Results also showed that participants in higher-intensity therapy trajectories had more severe clinical treatment courses and were more likely to be on capitated Medicaid plans, suggesting that capitated plans help to prioritize services for patients who need them most. Supporting policies that make psychosocial therapy available and accessible for those who may want it, rather than require therapy for buprenorphine treatment, may help retain patients in buprenorphine treatment.

CITATIONS

Samples, H., Williams, A. R., Crystal, S., & Olfson, M. (2022). Psychosocial and behavioral therapy in conjunction with medication for opioid use disorder: Patterns, predictors, and association with buprenorphine treatment outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 108774. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108774