Call Me! Phone Calls & Motivational Interviewing To Decrease Dropout

Treatment drop-out is unfortunately a common occurrence – studies suggest up to 30% of adults with substance use disorder (SUD) who enter outpatient treatment drop out within 1 month, and 50% before 3 months.

Various factors may predict whether patients will leave treatment including younger age and greater substance use severity. Treatment drop-out is problematic because, generally speaking, engagement and duration of treatment predict better substance use outcomes.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Clinical research is needed to develop and test optimal ways to re-engage patients who drop out of treatment.

Based on self-determination theory, having both requisite skill and autonomy (“having a say so”) in making a decision will contribute to greater intrinsic motivation to act in healthier ways. According to this theory, offering patients a choice of treatments could help promote re-engagement.

In the current study, McKay and colleagues tested whether a phone call from a clinician using motivational interviewing that aimed to either:

a) re-engage patients in the intensive outpatient program (IOP) or

b) re-engage patients in their choice of either intensive outpatient program (IOP) or one of three other treatment options, was more effective among patients who dropped out of outpatient substance use disorder (SUD) treatment.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

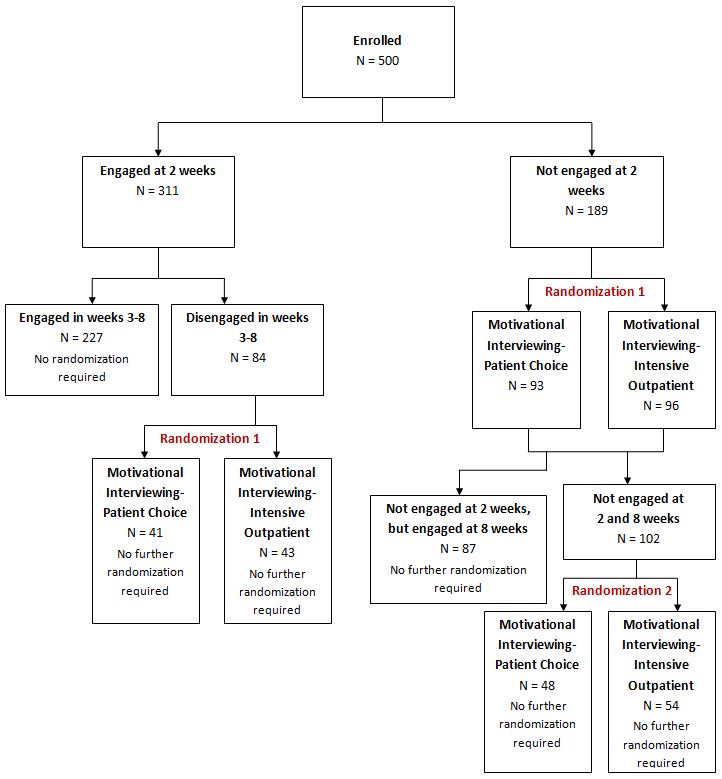

It was more complex than conventional randomized trials that randomly assign patients to a treatment at intake and test whether the treatments promoted different outcomes at discharge and follow-up. Specifically, patients with alcohol and cocaine use disorders (N = 500) who sought treatment at one of two intensive outpatient programs in Philadelphia, PA were followed initially for 2 weeks after they were scheduled to begin treatment.

Patients who were not yet engaged with treatment (defined differently at each setting due to different logistics of treatment, but reflecting general lack of attendance) were randomly assigned to receive:

- the phone call where the clinician delivered motivational interviewing to either re-engage patients in the IOP (MI-IOP)

OR

- motivational interviewing to engage them with a choice of treatment options, including the IOP as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy, telephone counseling, or medication management plus brief behavioral counseling (MI-PC).

Patients who were engaged with treatment at week 2 continued in the intensive outpatient program (IOP); if at any point between weeks 3 and 8 they dropped out (reflected by no IOP attendance for 2 consecutive weeks), they were randomly assigned to MI-IOP or MI-PC at that point. If patients who were not engaged at week 2 and were then randomly assigned to one of the MI conditions were still not engaged at week 8 (reflected by no IOP attendance during weeks 7 and 8), they were randomly assigned to MI-PC or no further outreach. Therefore, some patients may have received two MI-PC interventions.

Particularly salient sample characteristics included age (mean = 48 years), gender (81% male), ethnicity (88% African American), and marital status (85% not married). Of note, the sample was drawn from two parallel, identical studies with alcohol dependent or cocaine dependent patients but were combined due to high levels of co-occurrence between the two substance use disorders in these samples. Authors analyzed the data by presence of current/lifetime alcohol dependence (n = 428) or current/lifetime cocaine dependence (n = 409). Participants were assessed at baseline (treatment intake) as well as 4, 8, 12, and 24 weeks after baseline.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Among alcohol dependent patients, of the 161 not engaged at 2 weeks, 75 were engaged by week 8. Among cocaine dependent patients, of the 159 not engaged at 2 weeks, 75 were engaged by week 8.

Regarding group differences on treatment participation, there were generally no differences between the motivational interviewing (MI) conditions, or between MI and no outreach among those not engaged at all (although some differences were statistically significant [i.e., not likely due to chance], they were very small and not likely clinically significant, e.g., 1.3 sessions in MI-PC vs. .8 sessions in MI-IOP over 3 weeks).

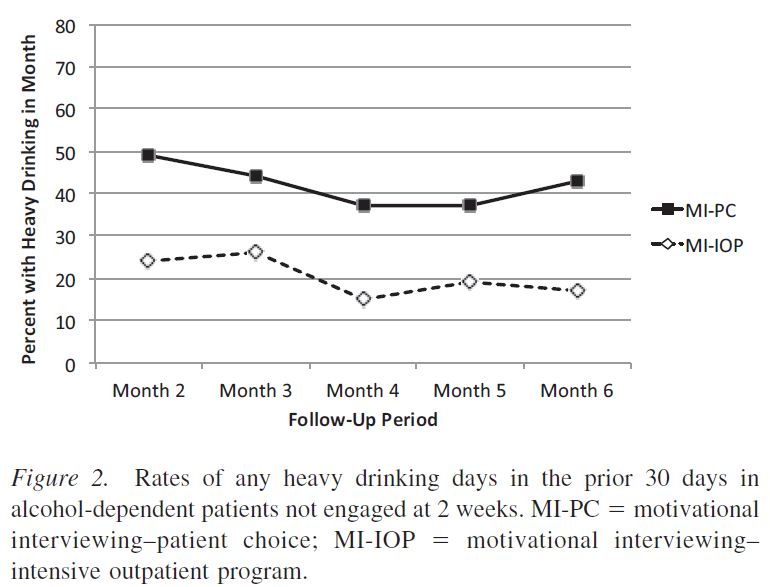

Interestingly, and contrary to the authors’ hypotheses, patients with alcohol dependence who were not engaged at week 2 that received MI-IOP had better alcohol use outcomes including lower likelihood of any drinking, of a heavy drinking day in the 30 days prior to assessment, and fewer percent days drinking and heavy drinking.

Among patients who initially engaged but dropped out during weeks 3 to 8, the motivational interviewing (MI) treatments had similar outcomes, while among those who were not engaged at either weeks 2 or 8, MI-PC and no outreach also generally had similar outcomes. The MI conditions did not differ for cocaine dependent patients on the cocaine outcomes. Analyses where only patients with both alcohol and cocaine dependence were included generally yielded parallel results (effect of MI-IOP for those who weren’t engaged at week 2 with similar outcomes in other comparisons)

Although it may seem intuitive that greater choice or autonomy would help increase patients’ treatment involvement, this was not the case in the current study. In fact, it generally led to worse outcomes among patients with alcohol use disorder. This type of result, however, is not uncommon.

For example, Walsh et al. (see here) found that among individuals referred to their employee assistance program for an alcohol-related problem, those assigned to a 12-step-based inpatient treatment program with 1-year continuing care had better abstinence rates and lower likelihood of treatment re-admission than patients allowed to choose their treatment (with many choosing either inpatient treatment or 12-step groups only).

In another study of two versions of 12-step facilitation by Walitzer et al., (see here), the directive version led to more 12-step attendance and better substance use outcomes than the version rooted in motivational interviewing (which offered greater choice and autonomy).

In the current study, both strategies used a motivational approach. This suggests a collaborative style, but perhaps not greater actual choice, is important to engaging patients. Consequently, patients appear to respond better to a prescription for something specific and may be looking for a directive from health care professionals rather than choices.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

This study could provide key information about effective strategies to re-engage patients who initially drop out of treatment, potentially increasing overall rates of abstinence & remission.

For patients that drop out of treatment early, an outreach phone call may help re-engage them in care; clinicians were able to re-engage about half of the patients initially not engaged in treatment at 2 weeks. The clinician making this phone call may wish to use a motivational (collaborative and empathic) approach that focuses on getting the patient to return to the original program at which they initially completed an intake.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The sample was almost 90% African American; it is unknown if the results would generalize to other racial/ethnic groups. Certain cultural traditions (including response to health care professionals such as a therapist) may have influenced treatment response in the current study but were not explored. Of note, the Walitzer study was almost 90% Caucasian, suggesting patients might benefit from a collaborative but firm clinical approach in facilitating re-engagement regardless of ethnicity.

- Another limitation is that although medication management was offered, the evidence for medications in the treatment of cocaine use disorder is very limited. That said, individuals with alcohol use disorder in this study were unlikely to choose medication management when given the choice. Thus, these primarily African American unmarried men with SUD in a major metropolitan city may not be very interested in medication to treat their addiction.

- Finally, other approaches in addition to motivational interviewing – such as a directive approach or providing incentives – were not tested and may have led to more patient re-engagement.

NEXT STEPS

The current study highlighted the need for interventions that attempt to re-engage patients who have dropped out of treatment. Future work may build on these motivational approaches, which appear to have promise.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Even if you decide not to engage with treatment or to drop out of treatment, phone calls with a therapist may help one consider the advantages and disadvantages of returning to treatment, which might increase motivation to engage in care.

- For scientists: Complex research designs such as the one used in the current study may help inform important but challenging clinical issues such as how best to re-engage individuals who have dropped out of care.

- For policy makers: Because third party payers typically only pay for services rendered to the patient, consider allotting funding for programs to implement outreach to patients that appear to have dropped out of treatment; these strategies may help re-engage patients and improve their substance use outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: For patients that complete intake assessments but do not initially engage in treatment, an outreach phone call with a motivational approach to re-engage them in care may help improve their outcomes. Although not discussed in the current study, lack of resources may prohibit such clinical activities, thus volunteers or other unpaid staff (e.g., interns) may be able to deliver these interventions under proper supervision.

CITATIONS

McKay, J. R., Drapkin, M. L., Van Horn, D. H., Lynch, K. G., Oslin, D. W., DePhilippis, D., . . . Cacciola, J. S. (2015). Effect of Patient Choice in an Adaptive Sequential Randomization Trial of Treatment for Alcohol and Cocaine Dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. doi:10.1037/a0039534