Does the Therapeutic Alliance Work By Increasing Self-Efficacy?

Studies have shown that the strength and quality of the bond between a therapist and patient – the therapeutic alliance – can have a substantial impact on psychotherapy outcomes. This is true too for individuals seeking treatment for alcohol use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Exactly how the alliance impacts abstinence and reduced drinking is not clear, however. This study by Maisto and colleagues investigated if the effect of a stronger therapeutic alliance on helping people stay sober was explained by boosting their abstinence self-efficacy, defined as the confidence to abstain from drinking when encountering risky or difficult situations that could trigger cravings to drink (e.g., being at a party where others are drinking).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary data analysis of Project MATCH, which compared cognitive-behavioral (CBT), motivational enhancement (MET), and Twelve-step facilitation (TSF) therapies for individuals with AUD. Although patients were recruited both from inpatient treatment and the community, these analyses only included those recruited from the community (i.e., the outpatient sample).

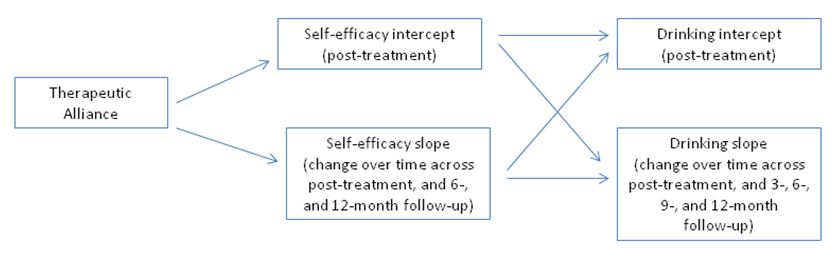

Authors conducted sophisticated analyses (three parallel process growth models) to investigate whether the alliance was associated with post-treatment drinking, as well as drinking across 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups; then, tested whether this effect was explained by changes in self-efficacy, measured at the end of treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. The parallel process growth models used in this study can help analyze longitudinal treatment and recovery pathways; that is, how individuals benefit from treatment and other recovery strategies over time.

The alliance was measured by the Working Alliance Inventory, a 36-item questionnaire broken down into three categories:

- task, or how often therapist/patient agree on therapy targets (“My therapist and I agree about the things I will need to do in counseling to help improve my situation.”)

- goal, or how often therapist/patient agree on therapy goals (“My therapist and I are working towards mutually agreed upon goals.”)

- bond, or how often the patient trusts the therapist or feels cared for/liked by him/her (“I am confident in my therapist’s ability to help me.”).

The alliance was measured, on average, at the end of week 2 (of 12 weeks of treatment). It assessed the alliance from the perspective of both the patient and the therapist.

There were three drinking outcomes:

- percent days drinking (PDD)

- drinks per drinking day (DDD)

- drinking-related consequences (DrInC)

These analyses controlled for gender and education, as well as baseline motivation, alcohol dependence severity, percent of treatment sessions attended, and baseline levels of self-efficacy and the outcome being tested.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The therapeutic alliance rated by the patient was related only to lower drinks per drinking day (DDD) at 6-month follow-up. When rated by the therapist, however, the alliance was related to DDD at post-treatment, 3-, 6-, and 9-month follow-ups. It was also related to lower 15-month percent days drinking (PDD). These effects were small in magnitude (~ r = .10 to .15). In the growth models, the alliance was associated consistently with post-treatment self-efficacy, post-treatment self-efficacy was related to better post-treatment drinking outcomes, and increased self-efficacy over time was related decreased drinking outcomes over time. However, the effect of the alliance on post-treatment drinking outcomes was not explained by increased self-efficacy from baseline to post-treatment for percent days drinking (PDD). Also, for drinks per drinking day (DDD) and the alcohol-related consequences score, measured by the drinking-related consequences (DrInC), abstinence self-efficacy only explained the effect of the alliance on post-treatment drinking and drinking consequences, but not for these outcomes over time.

There were also two interesting findings related to the MATCH treatments:

- First, therapists in motivational enhancement therapy (MET) reported a stronger alliance than therapists in twelve-step facilitation (TSF).

- Second, whether the alliance was associated with increased self-efficacy over time depended on the treatment to which the patient was assigned. For patients in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a better alliance was associated with increased self-efficacy over time, while for those in motivational enhancement therapy (MET) and twelve-step facilitation (TSF), a better alliance was actually associated with decreased self-efficacy over time. Yet, we know from prior studies that there was generally no difference in the drinking outcomes of these different treatment approaches.

Consistent with prior work, this study further confirmed that abstinence self-efficacy, and changes in self-efficacy over time, are one of the keys to understanding why some individuals have better drinking outcomes than others (see here).

While the therapeutic alliance may also be an important factor in how individuals benefit from alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment, its influence appeared to work through self-efficacy only during treatment, and only for certain drinking outcomes.

This is somewhat different from a recent secondary data analysis of the COMBINE study (see here), which examined various combinations of psychosocial and medication-assisted treatments for alcohol use disorder (AUD). In that study, for those receiving the psychosocial intervention only, associations between the Bond subscale of the same Working Alliance Inventory completed early in treatment, and percent days drinking (PDD) and drinking consequences 1 year after treatment, were explained by increased self-efficacy during treatment, measured by the same scale as in this study.

One difference between the studies was use of the total Working Alliance Inventory score in this study, and use of only the Bond subscale in the study using the COMBINE data. Because both studies investigated individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD), and are two of the most methodologically rigorous randomized trials in the field, the reason for these disparate findings is not certain.

More research is needed to understand the relationship between the therapeutic alliance, self-efficacy, and long-term drinking outcomes. That said, stronger alliances may be associated with post-treatment self-efficacy, which is known to be an important marker of a good prognosis.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

More information on the ways in which a strong alliance impacts alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment outcomes could help therapists make more concerted efforts to target these changes.

For example, if increased abstinence self-efficacy does explain the effect of the alliance on reduced drinking, therapists could work with patients to be sure they have a shared understanding of treatment goals and a specific plan on how risky situations will be addressed by the treatment.

The effect of the therapeutic alliance on self-efficacy over time only for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) patients is important to mention. CBT typically includes delivery of specific coping strategies with clear rationale for when and where to use them (e.g., drink refusal skills when offered a drink at a get-together).

The degree to which individuals are on the same page with, and trust, their therapists may lead to increased confidence to be able to use these skills.

On the other hand, motivational enhancement therapy (MET) does not explicitly deliver or facilitate skill practice. Also, the philosophy of twelve-step facilitation (TSF) is that treatment skills and benefit come not from the therapist, per se, but from resources available in community based 12-step mutual help organizations (e.g., reaching out to one’s sponsor for recovery support). Thus, the strength of the alliance may not be as important to developing confidence to achieve drinking goals in these other two treatments. Indeed, in line with this theory of how TSF works, studies of 12-step mutual-help participation after treatment have shown that greater attendance is associated with increased abstinence self-efficacy, particularly with respect to handling risky social situations (see here).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- In the analyses showing a positive effect, self-efficacy and drinking outcomes were both measured post-treatment (i.e., at the same time). It is not clear whether self-efficacy is influencing better drinking outcomes, or vice versa. It, too, may be a reciprocal relationship, where improvements and successes in abstinence or drinking reductions early in treatment lead to increased self-efficacy which, in turn, leads to better outcomes over time.

- Also, because this study included only MATCH outpatients, and the aftercare sample (recruited from inpatient treatment) had more severe alcohol use disorder (AUD), it is unclear whether these results may apply to more severe AUD patients.

NEXT STEPS

While both therapeutic alliance and self-efficacy are central constructs to understanding if and how people benefit from alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment, their relationship to each other is complex. The reasons why increased self-efficacy explains the association between alliance and improved drinking only for certain outcomes, and if the alliance is measured in a certain way, are not clear.

More research on the interplay between these variables during the early, middle, and later stages of alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment and recovery may help inform clinical interventions.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: The degree to which you believe your therapist understands your goals, have a shared understanding of the treatment plan, and feel respected by your therapist, may affect your ability to benefit from treatment. If you feel any of these qualities are missing, you may wish to bring up this issue with your therapist so it can be promptly addressed, or find a therapist that may be a better fit.

- For scientists: This was a methodologically sound secondary data analysis. Results showing the association between therapeutic alliance and drinking outcomes was explained by increased self-efficacy only during treatment, and only for drinking intensity and consequences, but not frequency. The findings are somewhat in contrast with another paper which showed that the association with drinking frequency 1 year after treatment was explained by increased self-efficacy during treatment. The relationships between the therapeutic alliance, self-efficacy, and drinking outcomes appear to be complex. More research may help uncover the processes by which a stronger alliance, and which aspects of the alliance, exerts influence on drinking outcomes.

- For policy makers: Consider funding studies on the effect of the therapeutic alliance on treatment and recovery outcomes. While research shows a better alliance can have a positive impact on alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment outcomes, exactly how and under what circumstances remains unclear.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The strength of your alliance with your patients can increase their confidence to handle difficult situations in their day-to-day life, particularly if you use a skills-based model like cognitive-behavioral therapy. If you are not doing so already, strongly consider efforts to build rapport early in treatment, and work to establish a set of goals and therapy targets on which you and your patients can agree.

CITATIONS

Maisto, S. A., Roos, C. R., O’Sickey, A. J., Kirouac, M., Connors, G. J., Tonigan, J. S., & Witkiewitz, K. (2015). The Indirect Effect of the Therapeutic Alliance and Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy on Alcohol Use and Alcohol-Related Problems in Project MATCH. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research, 39(3), 504-513. doi:10.1111/acer.12649