Increasing the availability of naloxone in communities can help prevent fatal overdose. This study investigated the feasibility and impact of paying cash to people who use drugs to distribute naloxone to other people who use drugs.

Increasing the availability of naloxone in communities can help prevent fatal overdose. This study investigated the feasibility and impact of paying cash to people who use drugs to distribute naloxone to other people who use drugs.

l

With the ongoing opioid overdose epidemic, novel strategies are needed to save lives. Naloxone can reverse overdoses from opioids and has been shown to reduce mortality. For example, distributing 100- 250 naloxone kits for each 100,000 members of the population is associated with a 46% decrease in opioid overdose mortality.

Naloxone is becoming increasingly available in a variety of settings, including pharmacies and clinics. However, research shows that naloxone has the greatest impact when there are few or no barriers to being able to administer this overdose reversal medication, whether it be in the emergency department or on the street. Accordingly, ensuring that naloxone is immediately available to people who use drugs, when they are using drugs, can help prevent fatal opioid overdoses.

One novel strategy for increasing the availability of naloxone in high-risk communities is through compensated peer models. In these models, people who are part of a given group are enlisted to help others in the group. For instance, people who use drugs can be paid to distribute naloxone to other people in their networks who use drugs, which can help scale access more efficiently and thereby reduce a community’s collective risk for overdose death. However, these models are not yet commonly implemented. In previous attempts at implementation, peers described issues with inadequate compensation and insufficient training and supervision.

The researchers in this study evaluated the feasibility and impact of implementing compensated peer models on naloxone distribution rates and cost. This research can demonstrate whether such models are feasible and cost-effective, which can lead to greater availability of naloxone within communities and save lives.

The research team observed the feasibility and early outcomes (i.e., number of naloxone kits distributed, any other harm reduction supplies distributed, costs, and narrative information) of compensated peer models that were implemented in 2 cities in Massachusetts from March 2021 through June 2022. As part of the HEALing Communities Study (i.e., a multisite study that aims to support communities in reducing opioid overdose deaths), coalitions in Holyoke and Gloucester, Massachusetts, supported local syringe service programs in implementing these programs.

In compensated peer models, people who use drugs (i.e., “peers”) are paid cash stipends to obtain naloxone kits and/or other harm reduction supplies from syringe service programs and distribute them directly to other people who use drugs in their social networks. Each kit contained 2 doses of naloxone nasal spray. Peers documented the number of naloxone kits distributed and the distribution location. In Gloucester only, any additional harm reduction supplies that were exchanged were also documented.

The study period also differed between the 2 communities. In Holyoke, the study took place between March 2021 and June 2022, for a total of 16 months. In Gloucester, the study took place between January 2022 and June 2022, for a total of 6 months.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the programs’ impact and feasibility. Narrative information was also obtained from syringe service program staff and peers via monthly data reporting and monthly coalition meeting minutes. The researchers used this narrative information to identify key program themes.

Peers were recruited from brick-and-mortar syringe service programs by program staff who noticed they visited frequently and were committed to overdose prevention. In Holyoke, peers were compensated $5 per naloxone kit, for a total of up to $25 per week, with a participation duration limit of 4 consecutive weeks but with an option to re-enroll. In Gloucester, peers were compensated $125 per week with no time limit on participation duration.

Among the peers in Holyoke, most were experiencing homelessness, spoke English as a second primary language, and/or engaged in sex work. In Gloucester, the majority of peers were either experiencing homelessness or were connected with the commercial fishing community.

The programs were feasible and cost-effective

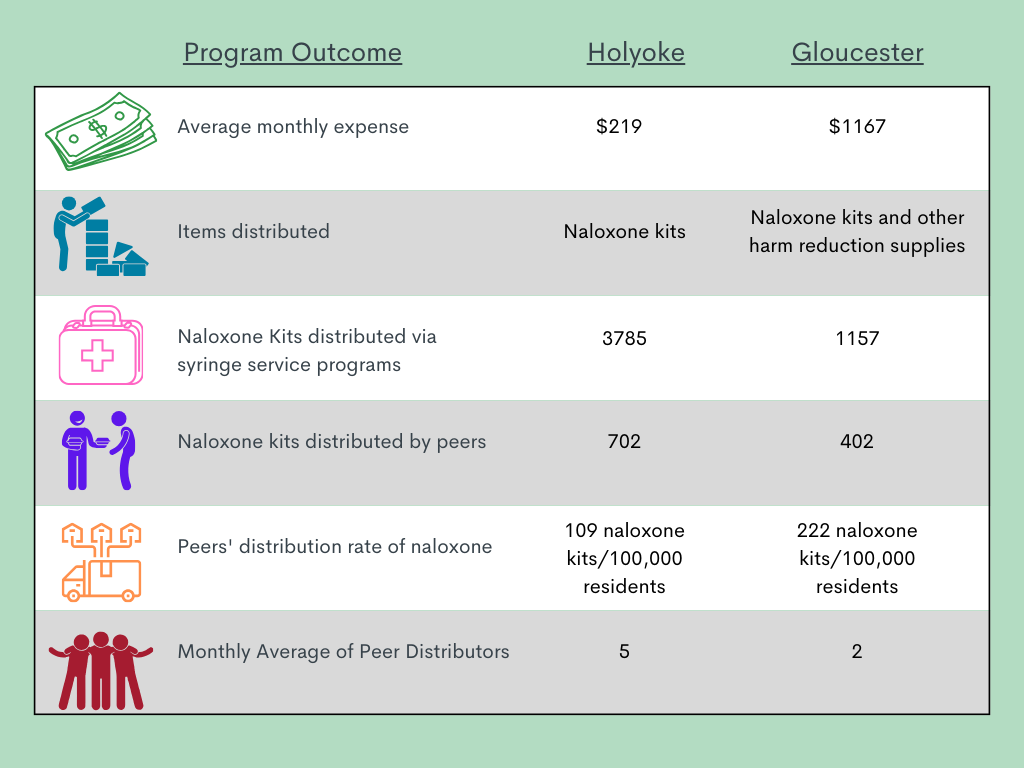

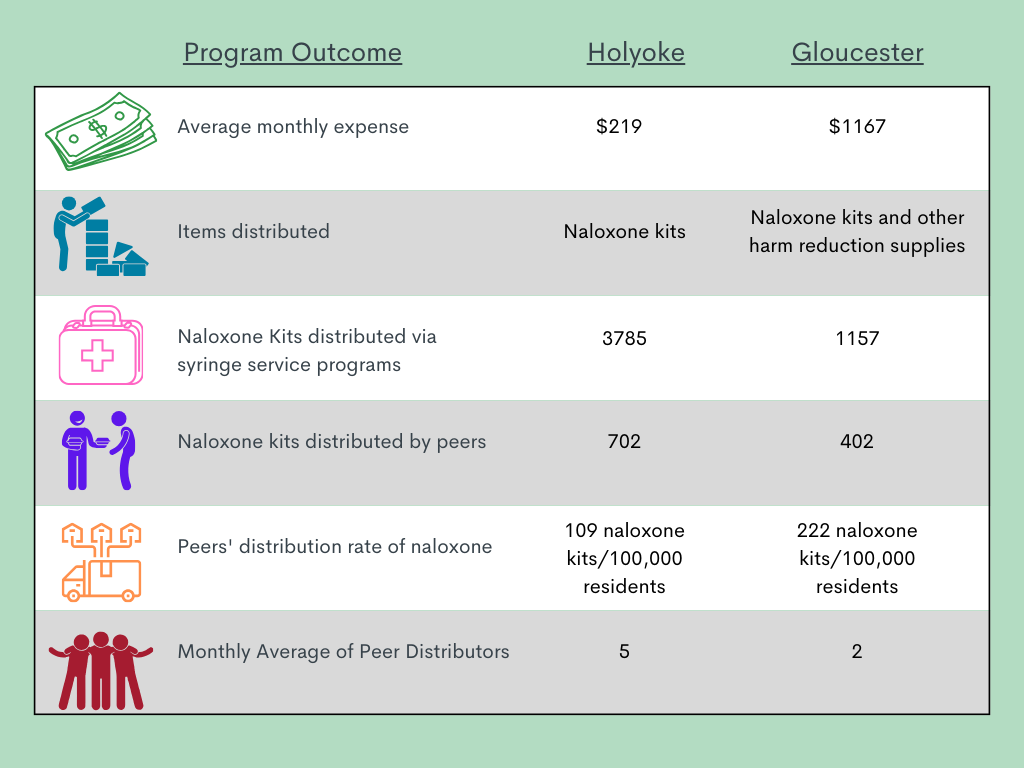

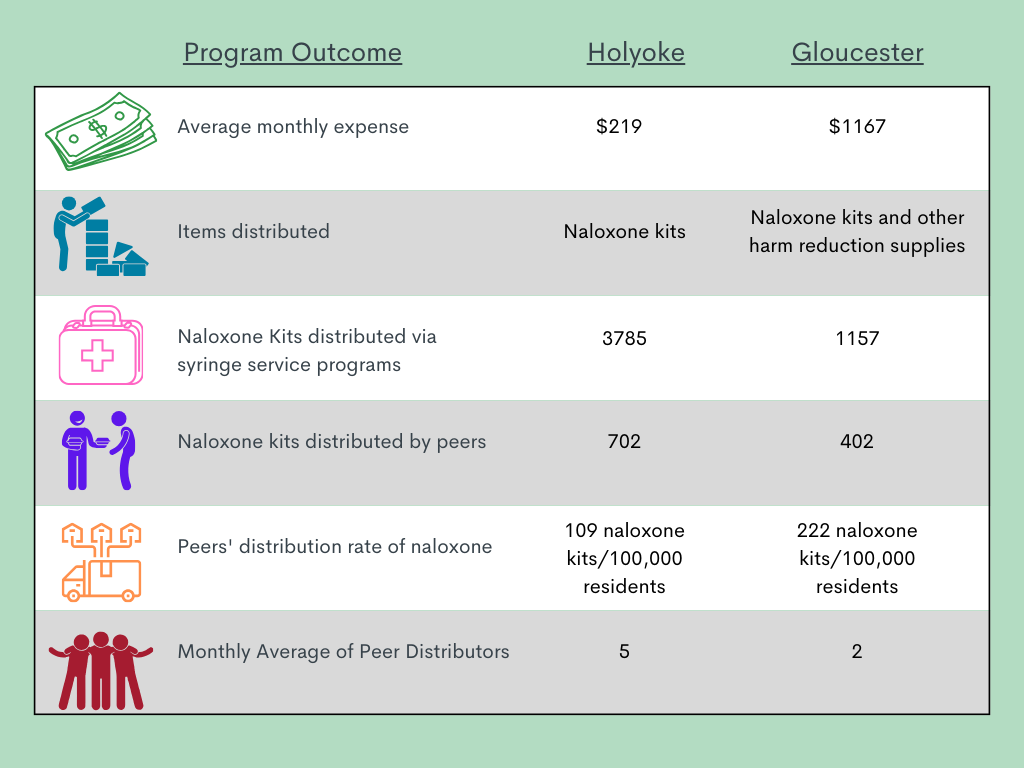

Across the two communities, peers distributed 1104 naloxone kits, averaging 56 kits per month. The total cost of the programs combined was $10,510. In Holyoke, peers distributed 16% of the syringe service program’s total naloxone distribution throughout the study period (March 2021 – June 2022), which equals 702 kits distributed, with an average of 44 kits per month. The total program cost was $3510. The rate of peer-distributed naloxone per 100,000 population was 109 kits per month.

In Gloucester, peers distributed 26% of the syringe service program’s total naloxone distribution throughout the study period (March 2021 – June 2022), which equals 402 kits distributed, with an average of 67 kits per month. The total program cost was $7000. The rate of peer-distributed naloxone per 100,000 population reached 222 kits per month. With funding outside of the current study, peers here also distributed other harm reduction supplies, including 138 fentanyl test strips, 40 sharps containers, 18 safer smoking kits, 16 safer snorting kits, 101 condoms, and 3568 syringes, in addition to collecting 2902 syringes for safe disposal.

The programs helped fill gaps in harm reduction outreach

In both communities, a key theme that emerged from the narrative data was how the compensated peer programs helped address some of the outreach gaps that the syringe service programs were experiencing. This included ongoing, uninterrupted distribution of naloxone despite COVID-related staff shortages. Also, staff noted that as the weather gets warmer, traditional outreach methods do not perform as well because people who use drugs may be more itinerant – moving from place to place. The novel peer-driven program, however, had its highest levels of distribution during this time period.

The research team examined the feasibility and impact of implementing compensated peer models. Implementing these models was feasible both practically and financially, and that they helped to fill some gaps in harm reduction outreach. Peers are in an advantageous position to expand access to naloxone among those at high risk of overdose and who are not currently accessing harm reduction services. In some states, naloxone is covered by insurance and can be obtained through standing orders or, more recently, over the counter. However, for lower income individuals experiencing homelessness, for example, free naloxone provided by peers may offer more seamless access to this life-saving resource. Accordingly, compensated peer models may offer an innovative strategy for increasing the availability of naloxone in communities. Of note, however, this study was conducted at 2 syringe service programs in Massachusetts, a state with more political and public support for harm reduction than most. Peer harm reduction models like these may be more challenging without the benefit of brick and mortar syringe service programs or without the support of state and local governments.

While this specific approach to peer models is novel, the concept of involving peers in harm reduction and recovery efforts is well-established. Alcoholics Anonymous, for instance, was founded in 1935, and Narcotics Anonymous was founded in 1953. More recently, peer outreach has similarly been used to connect people with medication-based treatment for opioid use disorder. These types of mutual help groups and peer recovery can be helpful to people trying to recover from a substance use disorder, as peers have personal experience with the challenges an individual in early recovery may be facing and can provide invaluable guidance and support.

Evaluating the model’s impact on mortality was beyond the goals of this study. However, the rate of distribution in this study was consistent with the distribution rate in previous work of 100 – 250 naloxone kits for each 100,000 members of the population, which was associated with a 46% decrease in opioid overdose mortality. Therefore, similar impacts on mortality could be reasonably expected and perhaps exceeded, given that the model “meets people where they are” and expands the access of naloxone to people who are not accessing traditional harm reduction services.

Paying peers to distribute naloxone to people who use drugs appears to be a feasible and affordable approach to increase the amount of naloxone available within communities and is likely to be highly cost-effective.

Lewis, N. M., Smeltzer, R. P., Baker, T. J., Sahovey, A. C., Baez, J., Hensel, E., … & Taylor, J. L. (2024). Feasibility of paying people who use drugs cash to distribute naloxone within their networks. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(1), 42. doi: 10.1186/s12954-024-00947-6.

l

With the ongoing opioid overdose epidemic, novel strategies are needed to save lives. Naloxone can reverse overdoses from opioids and has been shown to reduce mortality. For example, distributing 100- 250 naloxone kits for each 100,000 members of the population is associated with a 46% decrease in opioid overdose mortality.

Naloxone is becoming increasingly available in a variety of settings, including pharmacies and clinics. However, research shows that naloxone has the greatest impact when there are few or no barriers to being able to administer this overdose reversal medication, whether it be in the emergency department or on the street. Accordingly, ensuring that naloxone is immediately available to people who use drugs, when they are using drugs, can help prevent fatal opioid overdoses.

One novel strategy for increasing the availability of naloxone in high-risk communities is through compensated peer models. In these models, people who are part of a given group are enlisted to help others in the group. For instance, people who use drugs can be paid to distribute naloxone to other people in their networks who use drugs, which can help scale access more efficiently and thereby reduce a community’s collective risk for overdose death. However, these models are not yet commonly implemented. In previous attempts at implementation, peers described issues with inadequate compensation and insufficient training and supervision.

The researchers in this study evaluated the feasibility and impact of implementing compensated peer models on naloxone distribution rates and cost. This research can demonstrate whether such models are feasible and cost-effective, which can lead to greater availability of naloxone within communities and save lives.

The research team observed the feasibility and early outcomes (i.e., number of naloxone kits distributed, any other harm reduction supplies distributed, costs, and narrative information) of compensated peer models that were implemented in 2 cities in Massachusetts from March 2021 through June 2022. As part of the HEALing Communities Study (i.e., a multisite study that aims to support communities in reducing opioid overdose deaths), coalitions in Holyoke and Gloucester, Massachusetts, supported local syringe service programs in implementing these programs.

In compensated peer models, people who use drugs (i.e., “peers”) are paid cash stipends to obtain naloxone kits and/or other harm reduction supplies from syringe service programs and distribute them directly to other people who use drugs in their social networks. Each kit contained 2 doses of naloxone nasal spray. Peers documented the number of naloxone kits distributed and the distribution location. In Gloucester only, any additional harm reduction supplies that were exchanged were also documented.

The study period also differed between the 2 communities. In Holyoke, the study took place between March 2021 and June 2022, for a total of 16 months. In Gloucester, the study took place between January 2022 and June 2022, for a total of 6 months.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the programs’ impact and feasibility. Narrative information was also obtained from syringe service program staff and peers via monthly data reporting and monthly coalition meeting minutes. The researchers used this narrative information to identify key program themes.

Peers were recruited from brick-and-mortar syringe service programs by program staff who noticed they visited frequently and were committed to overdose prevention. In Holyoke, peers were compensated $5 per naloxone kit, for a total of up to $25 per week, with a participation duration limit of 4 consecutive weeks but with an option to re-enroll. In Gloucester, peers were compensated $125 per week with no time limit on participation duration.

Among the peers in Holyoke, most were experiencing homelessness, spoke English as a second primary language, and/or engaged in sex work. In Gloucester, the majority of peers were either experiencing homelessness or were connected with the commercial fishing community.

The programs were feasible and cost-effective

Across the two communities, peers distributed 1104 naloxone kits, averaging 56 kits per month. The total cost of the programs combined was $10,510. In Holyoke, peers distributed 16% of the syringe service program’s total naloxone distribution throughout the study period (March 2021 – June 2022), which equals 702 kits distributed, with an average of 44 kits per month. The total program cost was $3510. The rate of peer-distributed naloxone per 100,000 population was 109 kits per month.

In Gloucester, peers distributed 26% of the syringe service program’s total naloxone distribution throughout the study period (March 2021 – June 2022), which equals 402 kits distributed, with an average of 67 kits per month. The total program cost was $7000. The rate of peer-distributed naloxone per 100,000 population reached 222 kits per month. With funding outside of the current study, peers here also distributed other harm reduction supplies, including 138 fentanyl test strips, 40 sharps containers, 18 safer smoking kits, 16 safer snorting kits, 101 condoms, and 3568 syringes, in addition to collecting 2902 syringes for safe disposal.

The programs helped fill gaps in harm reduction outreach

In both communities, a key theme that emerged from the narrative data was how the compensated peer programs helped address some of the outreach gaps that the syringe service programs were experiencing. This included ongoing, uninterrupted distribution of naloxone despite COVID-related staff shortages. Also, staff noted that as the weather gets warmer, traditional outreach methods do not perform as well because people who use drugs may be more itinerant – moving from place to place. The novel peer-driven program, however, had its highest levels of distribution during this time period.

The research team examined the feasibility and impact of implementing compensated peer models. Implementing these models was feasible both practically and financially, and that they helped to fill some gaps in harm reduction outreach. Peers are in an advantageous position to expand access to naloxone among those at high risk of overdose and who are not currently accessing harm reduction services. In some states, naloxone is covered by insurance and can be obtained through standing orders or, more recently, over the counter. However, for lower income individuals experiencing homelessness, for example, free naloxone provided by peers may offer more seamless access to this life-saving resource. Accordingly, compensated peer models may offer an innovative strategy for increasing the availability of naloxone in communities. Of note, however, this study was conducted at 2 syringe service programs in Massachusetts, a state with more political and public support for harm reduction than most. Peer harm reduction models like these may be more challenging without the benefit of brick and mortar syringe service programs or without the support of state and local governments.

While this specific approach to peer models is novel, the concept of involving peers in harm reduction and recovery efforts is well-established. Alcoholics Anonymous, for instance, was founded in 1935, and Narcotics Anonymous was founded in 1953. More recently, peer outreach has similarly been used to connect people with medication-based treatment for opioid use disorder. These types of mutual help groups and peer recovery can be helpful to people trying to recover from a substance use disorder, as peers have personal experience with the challenges an individual in early recovery may be facing and can provide invaluable guidance and support.

Evaluating the model’s impact on mortality was beyond the goals of this study. However, the rate of distribution in this study was consistent with the distribution rate in previous work of 100 – 250 naloxone kits for each 100,000 members of the population, which was associated with a 46% decrease in opioid overdose mortality. Therefore, similar impacts on mortality could be reasonably expected and perhaps exceeded, given that the model “meets people where they are” and expands the access of naloxone to people who are not accessing traditional harm reduction services.

Paying peers to distribute naloxone to people who use drugs appears to be a feasible and affordable approach to increase the amount of naloxone available within communities and is likely to be highly cost-effective.

Lewis, N. M., Smeltzer, R. P., Baker, T. J., Sahovey, A. C., Baez, J., Hensel, E., … & Taylor, J. L. (2024). Feasibility of paying people who use drugs cash to distribute naloxone within their networks. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(1), 42. doi: 10.1186/s12954-024-00947-6.

l

With the ongoing opioid overdose epidemic, novel strategies are needed to save lives. Naloxone can reverse overdoses from opioids and has been shown to reduce mortality. For example, distributing 100- 250 naloxone kits for each 100,000 members of the population is associated with a 46% decrease in opioid overdose mortality.

Naloxone is becoming increasingly available in a variety of settings, including pharmacies and clinics. However, research shows that naloxone has the greatest impact when there are few or no barriers to being able to administer this overdose reversal medication, whether it be in the emergency department or on the street. Accordingly, ensuring that naloxone is immediately available to people who use drugs, when they are using drugs, can help prevent fatal opioid overdoses.

One novel strategy for increasing the availability of naloxone in high-risk communities is through compensated peer models. In these models, people who are part of a given group are enlisted to help others in the group. For instance, people who use drugs can be paid to distribute naloxone to other people in their networks who use drugs, which can help scale access more efficiently and thereby reduce a community’s collective risk for overdose death. However, these models are not yet commonly implemented. In previous attempts at implementation, peers described issues with inadequate compensation and insufficient training and supervision.

The researchers in this study evaluated the feasibility and impact of implementing compensated peer models on naloxone distribution rates and cost. This research can demonstrate whether such models are feasible and cost-effective, which can lead to greater availability of naloxone within communities and save lives.

The research team observed the feasibility and early outcomes (i.e., number of naloxone kits distributed, any other harm reduction supplies distributed, costs, and narrative information) of compensated peer models that were implemented in 2 cities in Massachusetts from March 2021 through June 2022. As part of the HEALing Communities Study (i.e., a multisite study that aims to support communities in reducing opioid overdose deaths), coalitions in Holyoke and Gloucester, Massachusetts, supported local syringe service programs in implementing these programs.

In compensated peer models, people who use drugs (i.e., “peers”) are paid cash stipends to obtain naloxone kits and/or other harm reduction supplies from syringe service programs and distribute them directly to other people who use drugs in their social networks. Each kit contained 2 doses of naloxone nasal spray. Peers documented the number of naloxone kits distributed and the distribution location. In Gloucester only, any additional harm reduction supplies that were exchanged were also documented.

The study period also differed between the 2 communities. In Holyoke, the study took place between March 2021 and June 2022, for a total of 16 months. In Gloucester, the study took place between January 2022 and June 2022, for a total of 6 months.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the programs’ impact and feasibility. Narrative information was also obtained from syringe service program staff and peers via monthly data reporting and monthly coalition meeting minutes. The researchers used this narrative information to identify key program themes.

Peers were recruited from brick-and-mortar syringe service programs by program staff who noticed they visited frequently and were committed to overdose prevention. In Holyoke, peers were compensated $5 per naloxone kit, for a total of up to $25 per week, with a participation duration limit of 4 consecutive weeks but with an option to re-enroll. In Gloucester, peers were compensated $125 per week with no time limit on participation duration.

Among the peers in Holyoke, most were experiencing homelessness, spoke English as a second primary language, and/or engaged in sex work. In Gloucester, the majority of peers were either experiencing homelessness or were connected with the commercial fishing community.

The programs were feasible and cost-effective

Across the two communities, peers distributed 1104 naloxone kits, averaging 56 kits per month. The total cost of the programs combined was $10,510. In Holyoke, peers distributed 16% of the syringe service program’s total naloxone distribution throughout the study period (March 2021 – June 2022), which equals 702 kits distributed, with an average of 44 kits per month. The total program cost was $3510. The rate of peer-distributed naloxone per 100,000 population was 109 kits per month.

In Gloucester, peers distributed 26% of the syringe service program’s total naloxone distribution throughout the study period (March 2021 – June 2022), which equals 402 kits distributed, with an average of 67 kits per month. The total program cost was $7000. The rate of peer-distributed naloxone per 100,000 population reached 222 kits per month. With funding outside of the current study, peers here also distributed other harm reduction supplies, including 138 fentanyl test strips, 40 sharps containers, 18 safer smoking kits, 16 safer snorting kits, 101 condoms, and 3568 syringes, in addition to collecting 2902 syringes for safe disposal.

The programs helped fill gaps in harm reduction outreach

In both communities, a key theme that emerged from the narrative data was how the compensated peer programs helped address some of the outreach gaps that the syringe service programs were experiencing. This included ongoing, uninterrupted distribution of naloxone despite COVID-related staff shortages. Also, staff noted that as the weather gets warmer, traditional outreach methods do not perform as well because people who use drugs may be more itinerant – moving from place to place. The novel peer-driven program, however, had its highest levels of distribution during this time period.

The research team examined the feasibility and impact of implementing compensated peer models. Implementing these models was feasible both practically and financially, and that they helped to fill some gaps in harm reduction outreach. Peers are in an advantageous position to expand access to naloxone among those at high risk of overdose and who are not currently accessing harm reduction services. In some states, naloxone is covered by insurance and can be obtained through standing orders or, more recently, over the counter. However, for lower income individuals experiencing homelessness, for example, free naloxone provided by peers may offer more seamless access to this life-saving resource. Accordingly, compensated peer models may offer an innovative strategy for increasing the availability of naloxone in communities. Of note, however, this study was conducted at 2 syringe service programs in Massachusetts, a state with more political and public support for harm reduction than most. Peer harm reduction models like these may be more challenging without the benefit of brick and mortar syringe service programs or without the support of state and local governments.

While this specific approach to peer models is novel, the concept of involving peers in harm reduction and recovery efforts is well-established. Alcoholics Anonymous, for instance, was founded in 1935, and Narcotics Anonymous was founded in 1953. More recently, peer outreach has similarly been used to connect people with medication-based treatment for opioid use disorder. These types of mutual help groups and peer recovery can be helpful to people trying to recover from a substance use disorder, as peers have personal experience with the challenges an individual in early recovery may be facing and can provide invaluable guidance and support.

Evaluating the model’s impact on mortality was beyond the goals of this study. However, the rate of distribution in this study was consistent with the distribution rate in previous work of 100 – 250 naloxone kits for each 100,000 members of the population, which was associated with a 46% decrease in opioid overdose mortality. Therefore, similar impacts on mortality could be reasonably expected and perhaps exceeded, given that the model “meets people where they are” and expands the access of naloxone to people who are not accessing traditional harm reduction services.

Paying peers to distribute naloxone to people who use drugs appears to be a feasible and affordable approach to increase the amount of naloxone available within communities and is likely to be highly cost-effective.

Lewis, N. M., Smeltzer, R. P., Baker, T. J., Sahovey, A. C., Baez, J., Hensel, E., … & Taylor, J. L. (2024). Feasibility of paying people who use drugs cash to distribute naloxone within their networks. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(1), 42. doi: 10.1186/s12954-024-00947-6.