Warrior Check Ups: Improving Alcohol Treatment for Military Members

Military members are more likely than civilians to drink and have drinking related problems, though they may be reluctant to seek help. This study tested the “Warrior Check Up”, a brief alcohol treatment that was delivered entirely by telephone.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Alcohol problems are common among military members – 20% are heavy drinkers (five or more drinks in a sitting at least weekly), a rate greater than their civilian counterparts. One third are likely to have a drinking problem based on the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT), a figure also higher than civilians. Overall, substance use disorder is the number one cause of lost work time in the military. At the same time only a small proportion of military members are referred for treatment.

The discrepancy between military members who need alcohol treatment & those who get it is even greater than for the general population. Part of this discrepancy may relate to obstacles to seeking treatment, including the stigma of having an alcohol problem in the military.

Members might fear that needing alcohol treatment is inconsistent with the military value of self-discipline, & that perception could affect their standing and ability to progress professionally.

Developing effective treatments that can also address this potential barrier are critical. This study attempted to overcome this barrier by developing and testing a brief telephone-based intervention for military members with alcohol use disorder.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Study participants were active duty army members with either alcohol or another drug use disorder (with DSM-IV diagnosis) at a base in the western United States. They were randomized to receive either a motivational interviewing plus feedback session (motivational interviewing (MI); N = 120) or a psychoeducational information session about the effects and consequences of alcohol and other drugs (Control; N = 122).

- MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Individuals in the motivational interviewing (MI) group received feedback about their drinking compared to other soldiers as well as civilians (non-soldiers) before the session. During the telephone session, they discussed this feedback, as well as costs and benefits of drinking and drug use, and how this substance use affects their goals and personal values. Both MI and Control phone sessions were delivered by trained, masters-level clinicians and lasted 60 minutes.

Main Study Outcomes:

(Measured at baseline, 3 & 6 month follow ups)

- Drinks per week over the past month

- Drinking frequency over the past month (as an ordinal variable – that is, ordered set of categories – from 0 to 10)

- Number of heavy drinking episodes (4+ drinks for women, and 5+ for men in one sitting) per week in the past month

- Presence of alcohol use disorder

- Consequences of substance use over the past 90 days, adapting a common measure of consequences to include military specific consequences (e.g., interfering with military promotion)

- Help-seeking behaviors measured by an 8-item inventory of professional treatment, faith-based counseling, and mutual-help participation

- STUDY DEMOGRAPHICS

-

Overall, study participants were virtually all male (92%), and mostly Caucasian (60%) and married (57%); they were 28 years old on average. Regarding their substance use histories, 83% met criteria for DSM-IV alcohol dependence, and 13% for alcohol abuse; 5% had another drug use disorder (a very small number had both alcohol and another drug use disorder). On average, participants had consumed 31 drinks over 4 days each week, including two heavy drinking episodes each week, during the month before beginning the study (about 8 drinks per drinking day).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

No difference between the groups in:

- Reduced number of drinking days or heavy drinking days: Both groups reduced number of drinking days per week from 4 to 3, and heavy drinking days from 2 to 1

- Substance use consequences: Substance use consequences improved in both groups

- Help seeking: Help seeking behaviors improved in both groups. For example, virtually none of the participants had attended a treatment session before the study, which increased to 15% attending at least 1 session by 3-month follow-up, which was maintained at the 6-month follow-up (13%).

Differences between the two groups in:

- Alcohol dependence: Motivational interviewing participants had reduced rates of alcohol dependence versus Control from baseline to 6-month follow-up (83% decreased to 22% in MI vs. 83% decreased to 35% in Control) that did not quite reach statistical significance.

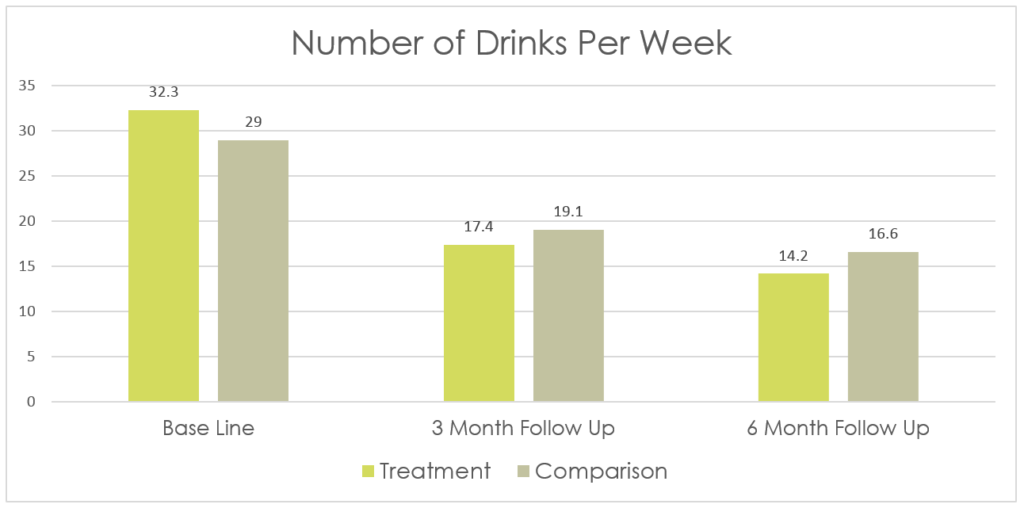

- Number of drinks per week: The motivational interviewing (MI) group improved slightly more over the 6 months of follow-up than Controls on number of drinks per week – though both groups got better.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

This study showed that brief interventions delivered by telephone may help reduce drinking and drinking-related consequences in military members.

The telephone-based motivational interviewing (MI) produced similar outcomes compared to just receiving factual information about alcohol and other drug use.

While research in other military settings are needed, psychoeducation could be just as helpful, while requiring fewer resources to deliver, as the more technical motivational interviewing (MI) – at least for a single session delivered by telephone. the study was innovative in its focus on alcohol treatment in a setting where seeking help may be stigmatized, as it is in the military. This type of approach could be applicable in any setting where individuals are worried about the perceptions of seeking help for an alcohol and other drug problems, such as in health care settings, for the staff themselves.

One other relevant piece in the findings is the low rates of drug use disorder apart from alcohol in the sample. This is consistent with military members on the whole where, unlike alcohol, they tend to have lower rates of other drug use and resulting problems. Experts suggest this may be due to consistent, ongoing drug testing in the military, and in a related sense, a broader military culture where illicit drug use is discouraged.

The one observed difference between the groups – from 32 to 14 weekly drinks in the motivational interviewing (MI) group versus 29 to 17 drinks in the control group – may not be associated with any real-world difference, given similar levels of consequences over time.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As the authors mention, it is difficult to say whether the intervention and psychoeducation caused the improvements because, although the study used a randomized design (which typically enhances our ability to say the intervention caused the improvement), it did not include a comparison group without any therapist contact. Since both the motivational interviewing (MI) and Control groups improved, we do not know whether these improvements would have happened naturally over time, without any intervention. This small but notable caveat did not detract from the very rigorous methods used in this study – including reassessment of participants on DSM-IV diagnosis, which is helpful to understand participants’ functioning over time, and there was a sound ethical reason for doing this – they did not want to keep participants from receiving any type of communication with a therapist.

- The results of this study are based off a single trial in an urban African American population thus generalizability to other geodemographic populations is not currently known. It could be more or less cost-effective in other populations.

NEXT STEPS

Next steps may be to develop and test other strategies to engage military personnel in alcohol and other drug treatment. Technology-based approaches, like mobile text message interventions, are being developed and tested in non-military at-risk populations with promising results. With more options at their disposal, the military will likely attract and engage more people that need help.

BOTTOM LINE

- For Individuals & families seeking recovery: A brief telephone-based alcohol treatment was helpful in reducing drinking for active military members in this study. Simply being asked about drinking and receiving alcohol education was just as helpful, suggesting this may be a simple and cost-effective intervention for military personnel. For military members, more research is needed to determine the best ways to help engage them in brief, effective treatment, though this approach is promising.

- For scientists: This randomized controlled trial of a telephone-delivered motivational interviewing plus feedback intervention showed the intervention was helpful, though in most cases, no more helpful than the assessment control condition. Moreover, it is unclear if the very small difference in drinking frequency, although statistically significant, would make an actual difference in soldiers’ functioning and health. Future studies could include a no-treatment control that are ethically sound (e.g., make the control group a waitlist-control group), that would help tease apart how much better the motivational interviewing (MI) intervention and an education only intervention are compared to receiving no intervention.

- For policy makers: This study outlines the evaluation of a potential tool to engage active military members with a current drinking problem, most of whom had alcohol use disorder. While more research is needed on exactly how the intervention should be delivered to be optimally helpful, these findings underscore brief, phone-delivered psychoeducation or motivational interviewing (MI) treatment as potentially useful resources and a way to address the burden of alcohol use disorder in the military.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study is relevant for treatment professionals working in the military or in other settings where people may be particularly reluctant to seek help for a substance use problem. It showed that either of these two brief interventions delivered by telephone may have promise as a way to reduce hazardous drinking and rates of alcohol use disorder.

CITATIONS

Walker, D. D., Walton, T. O., Neighbors, C., Kaysen, D., Mbilinyi, L., Darnell, J., … & Roffman, R. A. (2016). Randomized Trial of Motivational Interviewing Plus Feedback for Soldiers With Untreated Alcohol Abuse.