l

While effective treatments for substance use disorder exist, including medications and behavioral therapies, achieving long-term recovery remains challenging, as even the most highly efficacious interventions have limited long-term effectiveness. Digital health products, such as smartphone apps and websites, are increasingly used by individuals seeking to quit or reduce their drinking or drug use. These accessible tools have the potential to serve as an ongoing adjunct to traditional treatment or as a standalone support for those who prefer not to engage in formal treatment or face barriers to accessing care.

As of 2019, approximately 11% of individuals who had resolved a substance use problem used digital recovery supports, such as online mutual-help group meetings (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous), recovery-specific social networking sites (e.g., InTheRooms), and traditional social media platforms (e.g., Reddit, TikTok). Additionally, individuals in substance use treatment have shown interest in using digital tools alongside in-person care. Some evidence-based addiction-focused digital health tools exist, such as the Addiction – Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (A-CHESS) smartphone app. In a randomized controlled trial, individuals who used A-CHESS after treatment-as-usual (i.e., as continuing care) reported greater reductions in heavy drinking over 12 months compared to those receiving standard treatment and continuing care.

Despite their potential benefits, however, empirically supported digital tools designed to help people quit or reduce drinking or drug use have not yet been widely integrated into clinical settings. Meanwhile, hundreds of recovery-related apps are publicly available on app stores, accumulating millions of downloads, yet little is known about how individuals in formal treatment use these tools to support their recovery efforts. Understanding which apps are commonly used, the extent to which people use them, and whether individuals find them helpful could inform how empirically supported digital recovery supports can be more effectively integrated into existing treatment frameworks. This study aimed to fill that gap by examining how individuals in outpatient addiction treatment engage with smartphone apps and websites to support their recovery, including which apps and websites are most commonly used, how frequently and for how long they are engaged with, and whether individuals perceive them as helpful in supporting recovery.

This cross-sectional study surveyed 255 participants recruited from outpatient addiction treatment facilities in Rhode Island and Connecticut. To be eligible, participants had to be at least 18 years old and have received substance use treatment, such as counseling or medication, within the past year. The sample was predominantly White (85.1%), middle-aged (mean age = 41.4), and unemployed (67.5%), and about half were male (54.5%). The most frequently reported primary problem substances were heroin/fentanyl (31.8%) and cocaine (23.1%), followed by alcohol (21.2%), prescription opioids (6.3%), and methamphetamine (5.5%). Most participants (74.9%) had been diagnosed with substance use disorder 5 or more years ago.

The survey assessed participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, substance use history (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test and Drug Use Disorders Identification Test), and use of digital recovery tools. Participants first indicated which types of digital health products they used for recovery (e.g., apps, websites, social media, podcasts, and others). They then ranked the apps and websites by how frequently they used them and provided details on engagement with the products they had used, including: 1) how often they used each app or website (from [0] once a month or less to [5] once a day), 2) total number of uses for each app or website ([0] < 5 times to [6] 150+ times), 3) how long they used the app or website per session in which they used them ([0] a minute or two to [5] 60 minutes or more), 4) perceived helpfulness of the app or website to their recovery ([0] not at all to [4] quite a lot), 5) motivations for using the app or website (e.g. learning more about addiction, getting advice from others in recovery), and 6) how they engage with the app or website (e.g., liking, commenting, or sharing content posted by other users, inputting data or survey responses, reading/watching content, or “lurking”).

To analyze the data, the researchers calculated descriptive statistics to summarize participant demographics and digital recovery tool use patterns. First, individual models tested whether demographic factors (e.g., age and gender) or substance use disorder-related characteristics (e.g., severity, treatment history) predicted recovery app and website use one at a time. Then, for those associated with recovery app/website use individually, they were tested in a combined model simultaneously. Only age, gender, and employment status were examined. They also tested whether several patters of recovery app and website use (e.g., frequency, total interactions, total time, etc.) were linked to greater perceived benefits for recovery using the same approach.

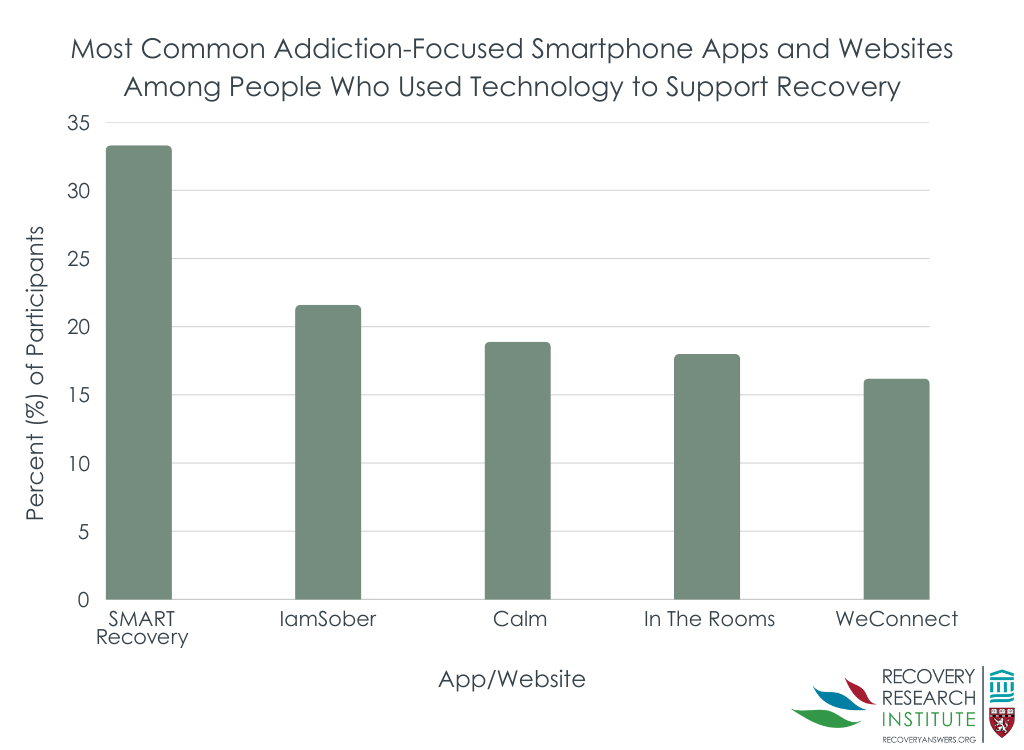

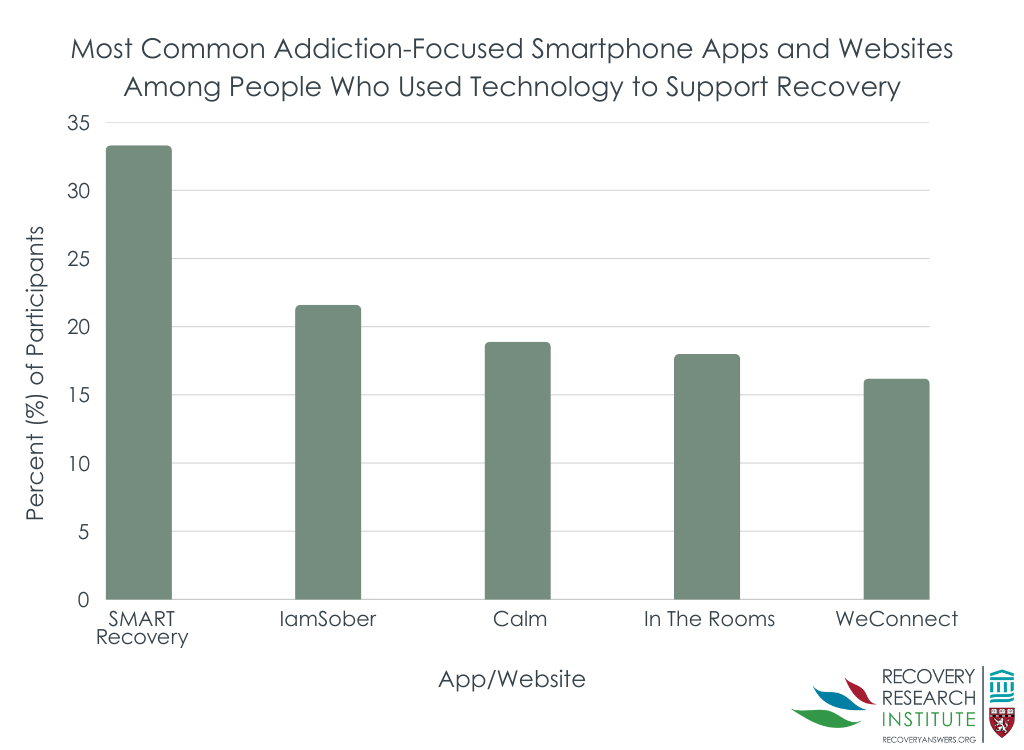

The use of apps and websites to support recovery was common

Nearly half (45%) of participants reported using a smartphone app or website to support their recovery (see Figure below for specific platforms). More than half (53.5%) of participants started using these apps or websites based on a recommendation from someone else. The most common sources of these recommendations were family members or friends not in recovery (67.2%) and counselors or therapists (44.3%), while fewer received recommendations from other individuals in recovery (11.5%). Among the 47% of individuals who discovered the apps they used on their own, most did so by searching online via Google or other search engines, with a smaller proportion (38%) finding them through app store searches. Top motivations for using an app or website to support recovery – cited by almost half of participants (44.6%) – were to learn more about addiction, receive advice from others in recovery, and enhance motivation to stay sober. Other common motivations included to help identify and avoid triggers (37.5%), to connect with others in recovery (32.1%), to track drinking and drug use to help maintain progress (28.6%), to help find treatment services or mutual-help group meetings (26.8%), or to practice mindfulness or meditation (26.7%). Women and younger adults were more likely to use apps and websites to support their recovery. Women were almost twice as likely to use an app or website to support their recovery as men. Additionally, older adults (ages 35+) were significantly less likely to have used an app or website to support their recovery compared to younger participants (ages 18–35-year-olds).

More frequent and long-term use of a recovery app or website was linked to greater perceived helpfulness

Among those who had ever used an app or website to support their recovery, over half (57.4%) used the tool 20 times or less, and about 1 in 5 (19.1%) used it fewer than 5 times. However, more than 1 in 4 (27.0%) used the app or website at least 50 times. Two-thirds (67.8%) reported using the app at least once a week, with more than 1 in 4 (27.0%) using the app at least once a day. Participants varied in how long they used these apps or websites during each session. Nearly half (45.3%) used the apps or websites for less than 5 minutes per session, while 15.7% used it for 30 minutes or more each time they checked it. Almost half (49.2%) used the apps or websites for only a few weeks or less, with 1 in 5 (21.1%) using them for just a few days. However, more than a quarter (27.2%) continued using the apps or websites for 6 months or more. Most participants rated the apps as beneficial to their recovery, with an average perceived helpfulness score of 3.8 out of 4. Using apps more frequently and for a longer period was associated with higher ratings of helpfulness. Those who used an app or website several times a day were more likely to rate it as “quite a lot” helpful (56%), compared to just 9% of those who used it once a month or less. Similarly, 50% of participants who reported using an app or website for a year or more found it to be very helpful, compared to only 19% of those who used it for just a few days. Another way of saying this is that app helpfulness likely led to greater use of it.

This study highlights the widespread use of digital recovery tools, such as apps and websites, among individuals in substance use treatment, but especially among women and younger patients. Engagement levels with digital recovery tools varied significantly. While some individuals used recovery apps or websites frequently and over extended periods of time, many engaged only a handful of times or for just a few days or weeks. Most participants found these tools helpful to their recovery, but, as one might expect, those who found them beneficial used them more often and over longer periods. This suggests that enhancing app design, content, and personalization to promote sustained engagement could increase their effectiveness. Despite their growing use, limited evidence exists supporting the efficacy of these digital recovery tools in improving substance-related outcomes, underscoring the need for further research to evaluate their clinical utility.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, research estimated that 11% of individuals who had resolved a substance use problem used digital recovery supports. However, as social distancing restrictions associated with the pandemic limited access to in-person services, adoption of online recovery supports (e.g., online mutual-help group meetings) increased. This study further contributes to that evolving landscape by showing that more people are also using apps and websites as digital recovery tools. Among these, SMARTRecovery.org was the most commonly used. While research on SMART Recovery as a mutual-help group is ongoing, no studies to date have examined the use or benefits of SMARTRecovery.org or other SMART-related digital tools. Similarly, other widely used apps or websites, such as In The Rooms, lack rigorous research assessing their efficacy, though some studies have explored user characteristics.

Collectively, findings from this study indicate many individuals in substance use treatment already use publicly available digital recovery apps or websites, yet evidence supporting their efficacy remains limited for many. While there is good evidence that certain apps produce a meaningful clinical benefit as noted above in the case of the A-CHESS app, more research is needed to assess different types of apps’ clinical value, especially those which are publicly available, as adjuncts to treatment or as standalone recovery supports.

Also, as noted above, women and younger adults (aged 18-35) were more likely to have used the apps than older adults and men, suggesting digital recovery tools may be particularly appealing to younger and female populations. Why this may be the case remains to be clarified. However, understanding potential barriers to adoption among older and male individuals could help to broaden accessibility and scalability. Notably, drug of choice was not associated with app use, suggesting opioid-, alcohol-, and stimulant-primary individuals had similar use of apps and websites to support their recovery.

Slightly more than half of participants were introduced to recovery apps through recommendations from family members and friends not in recovery or counselors and therapists. The remaining participants discovered them independently, most often using search engines like Google. This has important implications for dissemination efforts. Empirically supported addiction recovery support apps, such as A-CHESS, remain underutilized. One strategy to increase engagement with these tools may be to market them directly to addiction counselors and therapists, who can recommend them to clients. Additionally, direct -to-consumer marketing via social media and search engines may reach both individuals in recovery and their supportive family and friends who can recommend the use of these tools.

Although nearly half of participants had used an app or website to support their recovery, engagement patterns varied widely. While some individuals used apps frequently and over extended periods of time, the more common pattern was limited use (fewer than 20 total uses) over a shorter timeframe (a few weeks or less). Despite this variability in engagement, the vast majority of participants rated these apps as helpful, even among those who used them infrequently. However, those with more frequent and prolonged engagement reported greater perceived benefits. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating that higher engagement with empirically supported smartphone apps for substance use reduction is associated with improved outcomes, emphasizing the need to develop strategies that promote sustained engagement with digital recovery tools to enhance their effectiveness in supporting long-term recovery.

This study found that nearly half of individuals in outpatient substance use treatment had used an app or website to support their recovery. Most learned about these tools through from a wide range of sources including referrals from friends or family members that were not in recovery as well as from counselors and therapists, highlighting the importance of personal recommendations in spreading awareness of digital recovery resources. The most common motivations for using recovery apps and websites included learning more about addiction, receiving support from others in recovery, and enhancing motivation to maintain recovery. While some participants engaged with these apps frequently and over a long period of time, most used them infrequently and over a relative short period of time – typically just a few weeks or less. However, regardless of how often or how long they used these apps, the majority of participants perceived them as helpful to their recovery. Digital recovery tools may serve as a valuable complement to traditional treatment, but improving usability and engagement strategies will likely be key to maximizing their benefits. Additionally, there is limited research on the efficacy of the most commonly used recovery apps, highlighting the need for rigorous studies to determine whether they lead to measurable improvements in substance-related outcomes.

Wray, T. B., Reitzel, G., Phelan, C., Merrill, J. E., & Jackson, K. M. (2025). What apps and websites do those in treatment for substance-related problems use to help them in their recovery? A cross-sectional study of products and use patterns. Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment, 171. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2025.209631.

l

While effective treatments for substance use disorder exist, including medications and behavioral therapies, achieving long-term recovery remains challenging, as even the most highly efficacious interventions have limited long-term effectiveness. Digital health products, such as smartphone apps and websites, are increasingly used by individuals seeking to quit or reduce their drinking or drug use. These accessible tools have the potential to serve as an ongoing adjunct to traditional treatment or as a standalone support for those who prefer not to engage in formal treatment or face barriers to accessing care.

As of 2019, approximately 11% of individuals who had resolved a substance use problem used digital recovery supports, such as online mutual-help group meetings (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous), recovery-specific social networking sites (e.g., InTheRooms), and traditional social media platforms (e.g., Reddit, TikTok). Additionally, individuals in substance use treatment have shown interest in using digital tools alongside in-person care. Some evidence-based addiction-focused digital health tools exist, such as the Addiction – Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (A-CHESS) smartphone app. In a randomized controlled trial, individuals who used A-CHESS after treatment-as-usual (i.e., as continuing care) reported greater reductions in heavy drinking over 12 months compared to those receiving standard treatment and continuing care.

Despite their potential benefits, however, empirically supported digital tools designed to help people quit or reduce drinking or drug use have not yet been widely integrated into clinical settings. Meanwhile, hundreds of recovery-related apps are publicly available on app stores, accumulating millions of downloads, yet little is known about how individuals in formal treatment use these tools to support their recovery efforts. Understanding which apps are commonly used, the extent to which people use them, and whether individuals find them helpful could inform how empirically supported digital recovery supports can be more effectively integrated into existing treatment frameworks. This study aimed to fill that gap by examining how individuals in outpatient addiction treatment engage with smartphone apps and websites to support their recovery, including which apps and websites are most commonly used, how frequently and for how long they are engaged with, and whether individuals perceive them as helpful in supporting recovery.

This cross-sectional study surveyed 255 participants recruited from outpatient addiction treatment facilities in Rhode Island and Connecticut. To be eligible, participants had to be at least 18 years old and have received substance use treatment, such as counseling or medication, within the past year. The sample was predominantly White (85.1%), middle-aged (mean age = 41.4), and unemployed (67.5%), and about half were male (54.5%). The most frequently reported primary problem substances were heroin/fentanyl (31.8%) and cocaine (23.1%), followed by alcohol (21.2%), prescription opioids (6.3%), and methamphetamine (5.5%). Most participants (74.9%) had been diagnosed with substance use disorder 5 or more years ago.

The survey assessed participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, substance use history (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test and Drug Use Disorders Identification Test), and use of digital recovery tools. Participants first indicated which types of digital health products they used for recovery (e.g., apps, websites, social media, podcasts, and others). They then ranked the apps and websites by how frequently they used them and provided details on engagement with the products they had used, including: 1) how often they used each app or website (from [0] once a month or less to [5] once a day), 2) total number of uses for each app or website ([0] < 5 times to [6] 150+ times), 3) how long they used the app or website per session in which they used them ([0] a minute or two to [5] 60 minutes or more), 4) perceived helpfulness of the app or website to their recovery ([0] not at all to [4] quite a lot), 5) motivations for using the app or website (e.g. learning more about addiction, getting advice from others in recovery), and 6) how they engage with the app or website (e.g., liking, commenting, or sharing content posted by other users, inputting data or survey responses, reading/watching content, or “lurking”).

To analyze the data, the researchers calculated descriptive statistics to summarize participant demographics and digital recovery tool use patterns. First, individual models tested whether demographic factors (e.g., age and gender) or substance use disorder-related characteristics (e.g., severity, treatment history) predicted recovery app and website use one at a time. Then, for those associated with recovery app/website use individually, they were tested in a combined model simultaneously. Only age, gender, and employment status were examined. They also tested whether several patters of recovery app and website use (e.g., frequency, total interactions, total time, etc.) were linked to greater perceived benefits for recovery using the same approach.

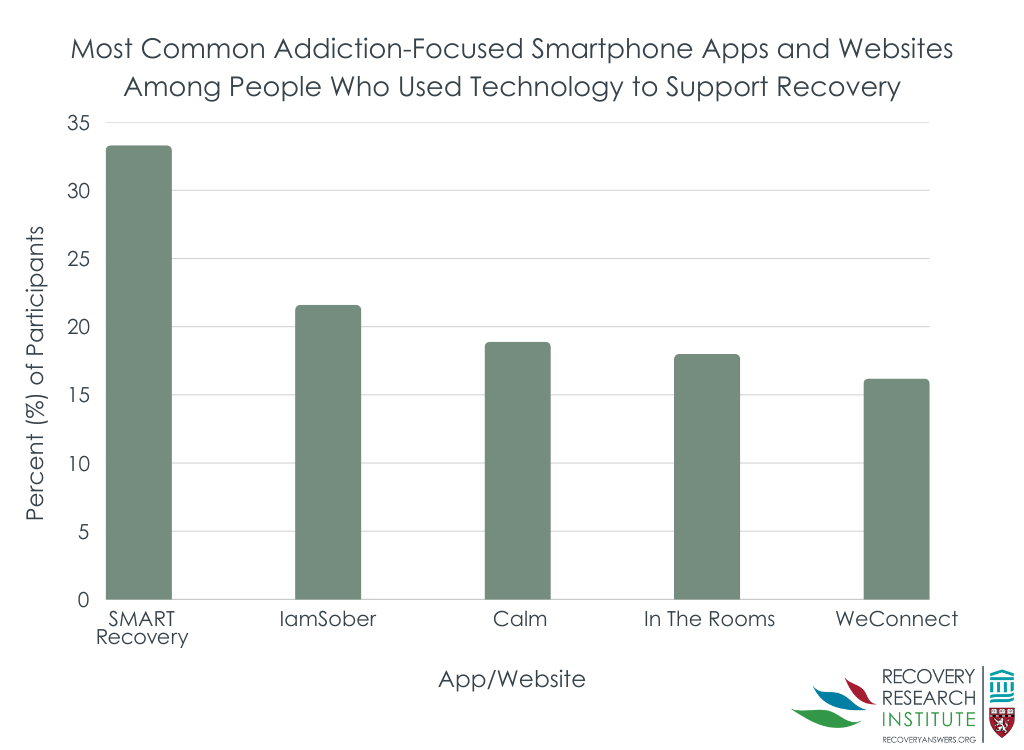

The use of apps and websites to support recovery was common

Nearly half (45%) of participants reported using a smartphone app or website to support their recovery (see Figure below for specific platforms). More than half (53.5%) of participants started using these apps or websites based on a recommendation from someone else. The most common sources of these recommendations were family members or friends not in recovery (67.2%) and counselors or therapists (44.3%), while fewer received recommendations from other individuals in recovery (11.5%). Among the 47% of individuals who discovered the apps they used on their own, most did so by searching online via Google or other search engines, with a smaller proportion (38%) finding them through app store searches. Top motivations for using an app or website to support recovery – cited by almost half of participants (44.6%) – were to learn more about addiction, receive advice from others in recovery, and enhance motivation to stay sober. Other common motivations included to help identify and avoid triggers (37.5%), to connect with others in recovery (32.1%), to track drinking and drug use to help maintain progress (28.6%), to help find treatment services or mutual-help group meetings (26.8%), or to practice mindfulness or meditation (26.7%). Women and younger adults were more likely to use apps and websites to support their recovery. Women were almost twice as likely to use an app or website to support their recovery as men. Additionally, older adults (ages 35+) were significantly less likely to have used an app or website to support their recovery compared to younger participants (ages 18–35-year-olds).

More frequent and long-term use of a recovery app or website was linked to greater perceived helpfulness

Among those who had ever used an app or website to support their recovery, over half (57.4%) used the tool 20 times or less, and about 1 in 5 (19.1%) used it fewer than 5 times. However, more than 1 in 4 (27.0%) used the app or website at least 50 times. Two-thirds (67.8%) reported using the app at least once a week, with more than 1 in 4 (27.0%) using the app at least once a day. Participants varied in how long they used these apps or websites during each session. Nearly half (45.3%) used the apps or websites for less than 5 minutes per session, while 15.7% used it for 30 minutes or more each time they checked it. Almost half (49.2%) used the apps or websites for only a few weeks or less, with 1 in 5 (21.1%) using them for just a few days. However, more than a quarter (27.2%) continued using the apps or websites for 6 months or more. Most participants rated the apps as beneficial to their recovery, with an average perceived helpfulness score of 3.8 out of 4. Using apps more frequently and for a longer period was associated with higher ratings of helpfulness. Those who used an app or website several times a day were more likely to rate it as “quite a lot” helpful (56%), compared to just 9% of those who used it once a month or less. Similarly, 50% of participants who reported using an app or website for a year or more found it to be very helpful, compared to only 19% of those who used it for just a few days. Another way of saying this is that app helpfulness likely led to greater use of it.

This study highlights the widespread use of digital recovery tools, such as apps and websites, among individuals in substance use treatment, but especially among women and younger patients. Engagement levels with digital recovery tools varied significantly. While some individuals used recovery apps or websites frequently and over extended periods of time, many engaged only a handful of times or for just a few days or weeks. Most participants found these tools helpful to their recovery, but, as one might expect, those who found them beneficial used them more often and over longer periods. This suggests that enhancing app design, content, and personalization to promote sustained engagement could increase their effectiveness. Despite their growing use, limited evidence exists supporting the efficacy of these digital recovery tools in improving substance-related outcomes, underscoring the need for further research to evaluate their clinical utility.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, research estimated that 11% of individuals who had resolved a substance use problem used digital recovery supports. However, as social distancing restrictions associated with the pandemic limited access to in-person services, adoption of online recovery supports (e.g., online mutual-help group meetings) increased. This study further contributes to that evolving landscape by showing that more people are also using apps and websites as digital recovery tools. Among these, SMARTRecovery.org was the most commonly used. While research on SMART Recovery as a mutual-help group is ongoing, no studies to date have examined the use or benefits of SMARTRecovery.org or other SMART-related digital tools. Similarly, other widely used apps or websites, such as In The Rooms, lack rigorous research assessing their efficacy, though some studies have explored user characteristics.

Collectively, findings from this study indicate many individuals in substance use treatment already use publicly available digital recovery apps or websites, yet evidence supporting their efficacy remains limited for many. While there is good evidence that certain apps produce a meaningful clinical benefit as noted above in the case of the A-CHESS app, more research is needed to assess different types of apps’ clinical value, especially those which are publicly available, as adjuncts to treatment or as standalone recovery supports.

Also, as noted above, women and younger adults (aged 18-35) were more likely to have used the apps than older adults and men, suggesting digital recovery tools may be particularly appealing to younger and female populations. Why this may be the case remains to be clarified. However, understanding potential barriers to adoption among older and male individuals could help to broaden accessibility and scalability. Notably, drug of choice was not associated with app use, suggesting opioid-, alcohol-, and stimulant-primary individuals had similar use of apps and websites to support their recovery.

Slightly more than half of participants were introduced to recovery apps through recommendations from family members and friends not in recovery or counselors and therapists. The remaining participants discovered them independently, most often using search engines like Google. This has important implications for dissemination efforts. Empirically supported addiction recovery support apps, such as A-CHESS, remain underutilized. One strategy to increase engagement with these tools may be to market them directly to addiction counselors and therapists, who can recommend them to clients. Additionally, direct -to-consumer marketing via social media and search engines may reach both individuals in recovery and their supportive family and friends who can recommend the use of these tools.

Although nearly half of participants had used an app or website to support their recovery, engagement patterns varied widely. While some individuals used apps frequently and over extended periods of time, the more common pattern was limited use (fewer than 20 total uses) over a shorter timeframe (a few weeks or less). Despite this variability in engagement, the vast majority of participants rated these apps as helpful, even among those who used them infrequently. However, those with more frequent and prolonged engagement reported greater perceived benefits. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating that higher engagement with empirically supported smartphone apps for substance use reduction is associated with improved outcomes, emphasizing the need to develop strategies that promote sustained engagement with digital recovery tools to enhance their effectiveness in supporting long-term recovery.

This study found that nearly half of individuals in outpatient substance use treatment had used an app or website to support their recovery. Most learned about these tools through from a wide range of sources including referrals from friends or family members that were not in recovery as well as from counselors and therapists, highlighting the importance of personal recommendations in spreading awareness of digital recovery resources. The most common motivations for using recovery apps and websites included learning more about addiction, receiving support from others in recovery, and enhancing motivation to maintain recovery. While some participants engaged with these apps frequently and over a long period of time, most used them infrequently and over a relative short period of time – typically just a few weeks or less. However, regardless of how often or how long they used these apps, the majority of participants perceived them as helpful to their recovery. Digital recovery tools may serve as a valuable complement to traditional treatment, but improving usability and engagement strategies will likely be key to maximizing their benefits. Additionally, there is limited research on the efficacy of the most commonly used recovery apps, highlighting the need for rigorous studies to determine whether they lead to measurable improvements in substance-related outcomes.

Wray, T. B., Reitzel, G., Phelan, C., Merrill, J. E., & Jackson, K. M. (2025). What apps and websites do those in treatment for substance-related problems use to help them in their recovery? A cross-sectional study of products and use patterns. Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment, 171. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2025.209631.

l

While effective treatments for substance use disorder exist, including medications and behavioral therapies, achieving long-term recovery remains challenging, as even the most highly efficacious interventions have limited long-term effectiveness. Digital health products, such as smartphone apps and websites, are increasingly used by individuals seeking to quit or reduce their drinking or drug use. These accessible tools have the potential to serve as an ongoing adjunct to traditional treatment or as a standalone support for those who prefer not to engage in formal treatment or face barriers to accessing care.

As of 2019, approximately 11% of individuals who had resolved a substance use problem used digital recovery supports, such as online mutual-help group meetings (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous), recovery-specific social networking sites (e.g., InTheRooms), and traditional social media platforms (e.g., Reddit, TikTok). Additionally, individuals in substance use treatment have shown interest in using digital tools alongside in-person care. Some evidence-based addiction-focused digital health tools exist, such as the Addiction – Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (A-CHESS) smartphone app. In a randomized controlled trial, individuals who used A-CHESS after treatment-as-usual (i.e., as continuing care) reported greater reductions in heavy drinking over 12 months compared to those receiving standard treatment and continuing care.

Despite their potential benefits, however, empirically supported digital tools designed to help people quit or reduce drinking or drug use have not yet been widely integrated into clinical settings. Meanwhile, hundreds of recovery-related apps are publicly available on app stores, accumulating millions of downloads, yet little is known about how individuals in formal treatment use these tools to support their recovery efforts. Understanding which apps are commonly used, the extent to which people use them, and whether individuals find them helpful could inform how empirically supported digital recovery supports can be more effectively integrated into existing treatment frameworks. This study aimed to fill that gap by examining how individuals in outpatient addiction treatment engage with smartphone apps and websites to support their recovery, including which apps and websites are most commonly used, how frequently and for how long they are engaged with, and whether individuals perceive them as helpful in supporting recovery.

This cross-sectional study surveyed 255 participants recruited from outpatient addiction treatment facilities in Rhode Island and Connecticut. To be eligible, participants had to be at least 18 years old and have received substance use treatment, such as counseling or medication, within the past year. The sample was predominantly White (85.1%), middle-aged (mean age = 41.4), and unemployed (67.5%), and about half were male (54.5%). The most frequently reported primary problem substances were heroin/fentanyl (31.8%) and cocaine (23.1%), followed by alcohol (21.2%), prescription opioids (6.3%), and methamphetamine (5.5%). Most participants (74.9%) had been diagnosed with substance use disorder 5 or more years ago.

The survey assessed participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, substance use history (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test and Drug Use Disorders Identification Test), and use of digital recovery tools. Participants first indicated which types of digital health products they used for recovery (e.g., apps, websites, social media, podcasts, and others). They then ranked the apps and websites by how frequently they used them and provided details on engagement with the products they had used, including: 1) how often they used each app or website (from [0] once a month or less to [5] once a day), 2) total number of uses for each app or website ([0] < 5 times to [6] 150+ times), 3) how long they used the app or website per session in which they used them ([0] a minute or two to [5] 60 minutes or more), 4) perceived helpfulness of the app or website to their recovery ([0] not at all to [4] quite a lot), 5) motivations for using the app or website (e.g. learning more about addiction, getting advice from others in recovery), and 6) how they engage with the app or website (e.g., liking, commenting, or sharing content posted by other users, inputting data or survey responses, reading/watching content, or “lurking”).

To analyze the data, the researchers calculated descriptive statistics to summarize participant demographics and digital recovery tool use patterns. First, individual models tested whether demographic factors (e.g., age and gender) or substance use disorder-related characteristics (e.g., severity, treatment history) predicted recovery app and website use one at a time. Then, for those associated with recovery app/website use individually, they were tested in a combined model simultaneously. Only age, gender, and employment status were examined. They also tested whether several patters of recovery app and website use (e.g., frequency, total interactions, total time, etc.) were linked to greater perceived benefits for recovery using the same approach.

The use of apps and websites to support recovery was common

Nearly half (45%) of participants reported using a smartphone app or website to support their recovery (see Figure below for specific platforms). More than half (53.5%) of participants started using these apps or websites based on a recommendation from someone else. The most common sources of these recommendations were family members or friends not in recovery (67.2%) and counselors or therapists (44.3%), while fewer received recommendations from other individuals in recovery (11.5%). Among the 47% of individuals who discovered the apps they used on their own, most did so by searching online via Google or other search engines, with a smaller proportion (38%) finding them through app store searches. Top motivations for using an app or website to support recovery – cited by almost half of participants (44.6%) – were to learn more about addiction, receive advice from others in recovery, and enhance motivation to stay sober. Other common motivations included to help identify and avoid triggers (37.5%), to connect with others in recovery (32.1%), to track drinking and drug use to help maintain progress (28.6%), to help find treatment services or mutual-help group meetings (26.8%), or to practice mindfulness or meditation (26.7%). Women and younger adults were more likely to use apps and websites to support their recovery. Women were almost twice as likely to use an app or website to support their recovery as men. Additionally, older adults (ages 35+) were significantly less likely to have used an app or website to support their recovery compared to younger participants (ages 18–35-year-olds).

More frequent and long-term use of a recovery app or website was linked to greater perceived helpfulness

Among those who had ever used an app or website to support their recovery, over half (57.4%) used the tool 20 times or less, and about 1 in 5 (19.1%) used it fewer than 5 times. However, more than 1 in 4 (27.0%) used the app or website at least 50 times. Two-thirds (67.8%) reported using the app at least once a week, with more than 1 in 4 (27.0%) using the app at least once a day. Participants varied in how long they used these apps or websites during each session. Nearly half (45.3%) used the apps or websites for less than 5 minutes per session, while 15.7% used it for 30 minutes or more each time they checked it. Almost half (49.2%) used the apps or websites for only a few weeks or less, with 1 in 5 (21.1%) using them for just a few days. However, more than a quarter (27.2%) continued using the apps or websites for 6 months or more. Most participants rated the apps as beneficial to their recovery, with an average perceived helpfulness score of 3.8 out of 4. Using apps more frequently and for a longer period was associated with higher ratings of helpfulness. Those who used an app or website several times a day were more likely to rate it as “quite a lot” helpful (56%), compared to just 9% of those who used it once a month or less. Similarly, 50% of participants who reported using an app or website for a year or more found it to be very helpful, compared to only 19% of those who used it for just a few days. Another way of saying this is that app helpfulness likely led to greater use of it.

This study highlights the widespread use of digital recovery tools, such as apps and websites, among individuals in substance use treatment, but especially among women and younger patients. Engagement levels with digital recovery tools varied significantly. While some individuals used recovery apps or websites frequently and over extended periods of time, many engaged only a handful of times or for just a few days or weeks. Most participants found these tools helpful to their recovery, but, as one might expect, those who found them beneficial used them more often and over longer periods. This suggests that enhancing app design, content, and personalization to promote sustained engagement could increase their effectiveness. Despite their growing use, limited evidence exists supporting the efficacy of these digital recovery tools in improving substance-related outcomes, underscoring the need for further research to evaluate their clinical utility.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, research estimated that 11% of individuals who had resolved a substance use problem used digital recovery supports. However, as social distancing restrictions associated with the pandemic limited access to in-person services, adoption of online recovery supports (e.g., online mutual-help group meetings) increased. This study further contributes to that evolving landscape by showing that more people are also using apps and websites as digital recovery tools. Among these, SMARTRecovery.org was the most commonly used. While research on SMART Recovery as a mutual-help group is ongoing, no studies to date have examined the use or benefits of SMARTRecovery.org or other SMART-related digital tools. Similarly, other widely used apps or websites, such as In The Rooms, lack rigorous research assessing their efficacy, though some studies have explored user characteristics.

Collectively, findings from this study indicate many individuals in substance use treatment already use publicly available digital recovery apps or websites, yet evidence supporting their efficacy remains limited for many. While there is good evidence that certain apps produce a meaningful clinical benefit as noted above in the case of the A-CHESS app, more research is needed to assess different types of apps’ clinical value, especially those which are publicly available, as adjuncts to treatment or as standalone recovery supports.

Also, as noted above, women and younger adults (aged 18-35) were more likely to have used the apps than older adults and men, suggesting digital recovery tools may be particularly appealing to younger and female populations. Why this may be the case remains to be clarified. However, understanding potential barriers to adoption among older and male individuals could help to broaden accessibility and scalability. Notably, drug of choice was not associated with app use, suggesting opioid-, alcohol-, and stimulant-primary individuals had similar use of apps and websites to support their recovery.

Slightly more than half of participants were introduced to recovery apps through recommendations from family members and friends not in recovery or counselors and therapists. The remaining participants discovered them independently, most often using search engines like Google. This has important implications for dissemination efforts. Empirically supported addiction recovery support apps, such as A-CHESS, remain underutilized. One strategy to increase engagement with these tools may be to market them directly to addiction counselors and therapists, who can recommend them to clients. Additionally, direct -to-consumer marketing via social media and search engines may reach both individuals in recovery and their supportive family and friends who can recommend the use of these tools.

Although nearly half of participants had used an app or website to support their recovery, engagement patterns varied widely. While some individuals used apps frequently and over extended periods of time, the more common pattern was limited use (fewer than 20 total uses) over a shorter timeframe (a few weeks or less). Despite this variability in engagement, the vast majority of participants rated these apps as helpful, even among those who used them infrequently. However, those with more frequent and prolonged engagement reported greater perceived benefits. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating that higher engagement with empirically supported smartphone apps for substance use reduction is associated with improved outcomes, emphasizing the need to develop strategies that promote sustained engagement with digital recovery tools to enhance their effectiveness in supporting long-term recovery.

This study found that nearly half of individuals in outpatient substance use treatment had used an app or website to support their recovery. Most learned about these tools through from a wide range of sources including referrals from friends or family members that were not in recovery as well as from counselors and therapists, highlighting the importance of personal recommendations in spreading awareness of digital recovery resources. The most common motivations for using recovery apps and websites included learning more about addiction, receiving support from others in recovery, and enhancing motivation to maintain recovery. While some participants engaged with these apps frequently and over a long period of time, most used them infrequently and over a relative short period of time – typically just a few weeks or less. However, regardless of how often or how long they used these apps, the majority of participants perceived them as helpful to their recovery. Digital recovery tools may serve as a valuable complement to traditional treatment, but improving usability and engagement strategies will likely be key to maximizing their benefits. Additionally, there is limited research on the efficacy of the most commonly used recovery apps, highlighting the need for rigorous studies to determine whether they lead to measurable improvements in substance-related outcomes.

Wray, T. B., Reitzel, G., Phelan, C., Merrill, J. E., & Jackson, K. M. (2025). What apps and websites do those in treatment for substance-related problems use to help them in their recovery? A cross-sectional study of products and use patterns. Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment, 171. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2025.209631.