Addressing Legal Problems in Addiction Treatment

There is an ongoing debate about the role of the legal system in addressing substance use disorder and related health and societal problems. This study investigated the impact of legal problems in a group of methadone patients that also had cocaine use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

For those with opioid use disorder seeking treatment, 65% also use cocaine, which has its own set of negative consequences including but not limited to worse opioid medication treatment outcomes. In addition to focusing on professional treatments for these individuals, it is also critical to identify social and contextual factors that might help improve outcomes. Given the current policy debates centering on whether the escalation in opioid overdoses (33,000 deaths in 2015) is best addressed from criminal justice (i.e., using the legal system to prevent consequences and effect change), public health (i.e., using healthcare systems and community organizations to prevent consequences and effect change), or both perspectives, the impact of legal problems is a pivotal piece of the issue.

If justice system involvement – and the contingencies that comes along with it, such as ongoing drug testing – improve outcomes, it may be helpful to examine what is working here, maximize this, and tap into this to enhance public health. Conversely, if justice system involvement worsens outcomes, it may be helpful to examine the barriers it presents, and how those can be more effectively remedied from a public health perspective. This study by Ginley and colleagues investigated whether legal problems are related to cocaine outcomes and ongoing illegal activity for individuals already receiving methadone for their opioid use disorder.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study combined data from four separate randomized controlled trials that tested motivational, financial incentives (i.e., contingency management) for cocaine use in 323 individuals receiving methadone for their opioid use disorder who also had cocaine use disorder.

- MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Of these individuals, 83 entered treatment with legal problems and 240 without legal problems, based on the Addiction Severity Index – they needed to report, for example, that they were awaiting charges, trial, or sentencing, or committed an illegal activity in the past 30 days, reported subjective legal problems, or desired a referral for legal concerns. The legal problems group reported 6 days of illegal activity, on average, in the past month when entering the study.

To try and isolate the influence of legal problems, study authors adjusted for many ways in which the groups were different from the start (e.g., the legal problem group had more alcohol, drug, and family/social problems). Of note, the groups were similar in terms of age, gender, race/ethnicity, methadone dose, cocaine positive toxicology screen (“tox” screen), and the proportions with alcohol and cocaine use disorder.

Primary outcomes were: 1) proportion of cocaine negative toxicology screens – signifying cocaine abstinence – and longest duration of abstinence based on urine tox screens at both 3-months and 6-months after entering the study, and 2) illegal activity just at 6 months because at 3 months prior charges may have lingered and authors were interested in the onset of new legal problems.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

During treatment – 3 months after entering the study – for individuals with legal problems 34% of their tox screens were cocaine negative (where if a participant misses a tox screen it is counted as having used cocaine) compared to 44% for those without legal problems, a statistically significant difference.

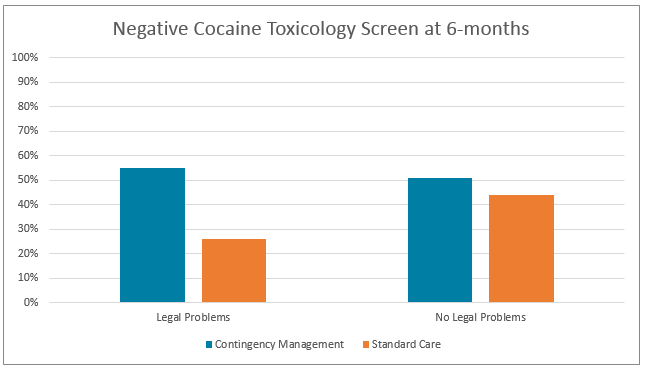

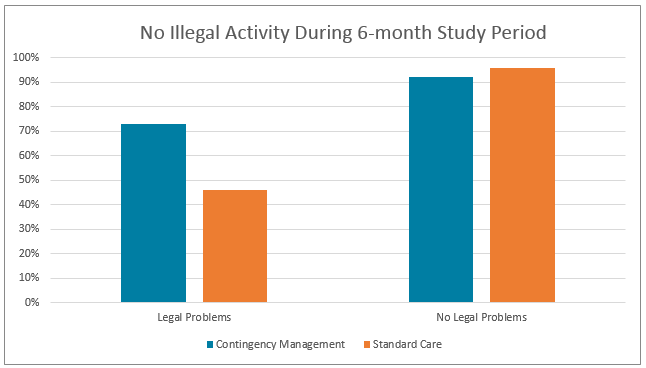

There were some additional noteworthy findings at the 6-month follow-up. The figures below help illustrate the most important study findings. That is, at the follow-up – 6 months after entering the study – the relationship between legal problems and cocaine use were found to depend on whether the individual had received additional motivational incentives (“contingency management”) for being abstinent from cocaine in addition to their methadone treatment for opioids. If they did not have legal problems, getting the motivational incentives did not make a difference to their outcomes. On the other hand, if they had legal problems, those getting the motivational incentives did better. The results were similar when looking at illegal activity over the entire study period.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

For individuals receiving methadone in this study – that combined data from four separate randomized controlled trials – having one or more self-reported legal problems, based on the Addiction Severity Index, was related to worse cocaine outcomes and greater likelihood of new onset legal problems. These findings seem to run somewhat counter to what is often observed in other recovery research studies– individuals mandated to treatment by the criminal justice system usually have similar or even better outcomes compared to those who are not mandated by the criminal justice system. It could be the less severe clinical profile that mandated treatment patients have compared to those arriving in treatment more voluntarily are helping to account for this frequent, somewhat counter-intuitive, finding. Also, either in addition or alternatively, the incentive to avoid jail/prison by engaging in ongoing drug use monitoring via toxicology screens and remaining in treatment could be driving these similar or better outcomes, in fact, some of the best outcomes in treatment and recovery research come from programs with powerful incentives for abstinence and treatment engagement with immediate consequences.

For the 24/7 Sobriety program, individuals with multiple DUIs are required to maintain abstinence from alcohol and prove this by self-administering a breathalyzer twice a day; if they miss the tests or the tests are positive for alcohol, there is an immediate, albeit modest consequence of 1-2 nights in jail. This contingency management paradigm done this way results in 99% alcohol negative tests.

It is not entirely clear why legal problems were related to worse outcomes in the study. One possibility is that legal problems are simply a marker of greater recovery challenges – for example individuals from a lower socioeconomic background may be more vulnerable to criminal justice involvement and have less recovery capital to buffer against relapse risk. This is possible, though less likely given that study authors adjusted for many of these potential factors associated with having a more severe addiction profile. This explanation for the findings though – legal problems as a marker for greater recovery challenges – cannot be ruled out entirely. For example, those with legal problems might have a criminally risky social network of friends. These social network impacts might have lasting effects.

A second possibility is that the added stress of legal difficulties could over-burden an individual’s ability to cope with recovery-related challenges, leading to worse outcomes. A third possibility is that legal problems could make it difficult to find a keep a job, or to obtain stable housing, both of which could in turn impact substance related outcomes. Because a range of circumstances were included in “having a legal problem” in this study, and the study participants were amalgamated from four separate studies all in methadone treatment, it is difficult to say what is truly accounting for the worse cocaine outcomes.

Nevertheless, an important finding is that being in the motivational incentive/contingency management group helped buffer against the worse outcomes authors found for those with legal problems – suggesting these individuals benefit from more reward for abstinence to overpower whatever difficulties are holding them back. In other words, the challenges faced by the individuals with legal problems in this study were not insurmountable and could be clinically influenced.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- In addition to the main limitation of being unable to determine what accounts for the relationship between legal problems and worse cocaine outcomes, authors amalgamated data from four separated studies published from the early to mid-2000s when buprenorphine/naloxone (as brand name Suboxone) was not FDA approved or was not widely available. Compared to methadone, this is a preferred medication as a first-line for opioid use disorder given the added flexibility with which it can be prescribed – i.e., by physicians in the community – and its partial rather than full agonism (i.e., stimulation) of the opioid receptors. Thus whether the findings apply to individuals on all types of opioid medications is not clear.

- Opioid outcomes were not analyzed in this paper – motivational incentives/contingency management for cocaine use was the focus of the study.

- “Legal problems” were defined in a very broad manner and measured by self-report only, rather than by some sort of formal record keeping database.

NEXT STEPS

One potentially fruitful next step may be to conduct qualitative interviews with individuals who have legal problems. This might help the field understand more fully the challenges related to having a legal problem, and thus offer ideas on how to help remedy them. Also, more specific examination of the nature and degree of “legal problems” that patients present with in treatment and how these influence responses to treatment would be important to know, as it is likely that different types of problems (e.g., being on probation vs. reporting a legal problem) could confer different degrees of burden and/or motivation for abstinence.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: For individuals with both an opioid use and cocaine use disorder in methadone treatment, having legal problems in this study was related to worse cocaine outcomes. While unclear why this was the case, motivational incentives (i.e., contingency management) helped make up for this disadvantage. For several reasons – including the broad definition of legal problems — the implications of the study are not 100% clear. Other prior research -has found similar or better outcomes for individuals involved in the criminal justice system, which runs opposite to these study findings. Given the high stakes around how best to address substance use disorder, more rigorous research is needed before definitive statements can be made about the impact of legal problems and the potential role of the criminal justice system in treatment and recovery outcomes.

- For scientists: The presence of legal problems moderated the benefit of contingency management for co-occurring cocaine use disorder among patients receiving methadone for opioid use disorder. For those with legal problems, motivational incentives/contingency management for cocaine use was needed as an addition to standard care to enhance outcomes so they were ultimately as good as those without legal problems. For those without legal problems, receiving motivational incentives/contingency management provided no added benefit to standard methadone care. Because legal problems in this study include a range of different variables from being on parole to simply self-reporting a legal problem, and authors amalgamated the data from four separate studies, the study implications are not 100% clear. Indeed, prior research has found similar or better outcomes for individuals involved in the criminal justice system. Given the high stakes around the potential harms of criminal justice involvement as well, more rigorous research is needed to understand the potential role of the criminal justice system in treatment and recovery outcomes.

- For policy makers: For individuals with both an opioid use and cocaine use disorder in methadone treatment, having legal problems in this study was related to worse cocaine outcomes. While it is unclear why this was the case, motivational incentives (i.e., contingency management) helped make up for this disadvantage. For several reasons – including the broad definition of legal problems — the implications of the study are not 100% clear. Other prior research has found similar or better outcomes for individuals involved in the criminal justice system, which runs opposite to these study findings. Given the high stakes around how best to address substance use disorder, funding to conduct more rigorous research is needed to understand the potential impact of the presence of legal problems and the role of the criminal justice system in treatment and recovery outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: For individuals with both an opioid use and cocaine use disorder in methadone treatment, having legal problems in this study was related to worse cocaine outcomes. While unclear why this was the case, motivational incentives (i.e., contingency management) helped make up for this disadvantage. For several reasons – including the broad definition of legal problems — the implications of the study are not 100% clear. Other prior research has found similar or better outcomes for individuals involved in the criminal justice system, which runs opposite to these study findings. Given the high stakes around how best to address substance use disorder, more rigorous research is needed before definitive statements can be made about the potential role of the criminal justice system in treatment and recovery outcomes.

CITATIONS

Ginley, M. K., Rash, C. J., Olmstead, T. A., & Petry, N. M. (2017). Contingency management treatment in cocaine using methadone maintained patients with and without legal problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180, 208-214.