Are there different types of adolescent drinkers that can benefit from targeted interventions?

Alcohol use is the most harmful risk factor for disease, disability, and premature death in adolescents. Thus, effective strategies to identify and address adolescent drinking is critical to their health and well-being. In this study, authors examined three different adolescent drinking patterns, their long-term consequences, and childhood factors that predicted these patterns.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Policy interventions aimed at adolescent drinking have had mixed results, with some showing evidence of preventing underage drinking, yet most showing no effect at all. The absence of definitive results may be explained by natural variability in the types of adolescent drinkers the policies are intended to address. Also, adolescent drinking may change over time so that a policy or prevention strategy may only be effective for one group at one point in time. Interventions that take these individual differences into account may better target certain groups of adolescents, thus producing better outcomes. In the current study, Boden and colleagues aimed to identify different classes of adolescent drinkers, how these adolescent drinking patterns predicted adult drinking outcomes, and childhood factors associated with the riskiest drinking patterns. Information from this type of analysis could be used to inform targeted alcohol policy and prevention strategies for adolescent drinkers.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used a naturalistic, longitudinal design that followed 994 adolescents into early adulthood, initially identifying different groups of adolescent drinkers along with childhood factors associated with each group, then following each group over time to assess adult drinking outcomes at five different follow-ups. The study was conducted in Christchurch, New Zealand and used a study sample (n=1265) that consisted of a group of people from birth to adulthood (also known as a birth cohort). Adolescents, ages 14-16, were categorized into different drinking groups using a sophisticated statistical technique based on their alcohol consumption in the past year. Study participants reported the frequency with which they consumed alcohol and the number of drinks consumed on a typical drinking occasion. Next, authors examined how these adolescent drinking patterns related to adult drinking outcomes, including percentage that met criteria for alcohol use disorder based on criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV), the number of alcohol use disorder symptoms, and the amount of alcohol consumed in the past year. That is, they examined whether these types of adolescent drinkers had different adult drinking outcomes, after controlling for confounding variables. This statistical control was done to try and isolate the effect of adolescent drinking class on adult drinking outcomes, which would increase their ability to make inferences that the adolescent drinking behaviors caused the adult drinking outcomes. They also examined differences between the adolescent drinking types on several childhood variables, to identify potential risk factors that might be addressed via prevention or intervention. These childhood variables included family socioeconomic and demographic background, individual personality traits, behavioral factors (e.g., child conduct problems and novelty-seeking), family functioning, parental behavior, and trauma. Data from the birth cohort was collected from 1977 to 2012 with a follow-up rate of the surviving sample near 80% for the five different times that data was collected in adulthood.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Authors identified three classes of adolescent alcohol use.

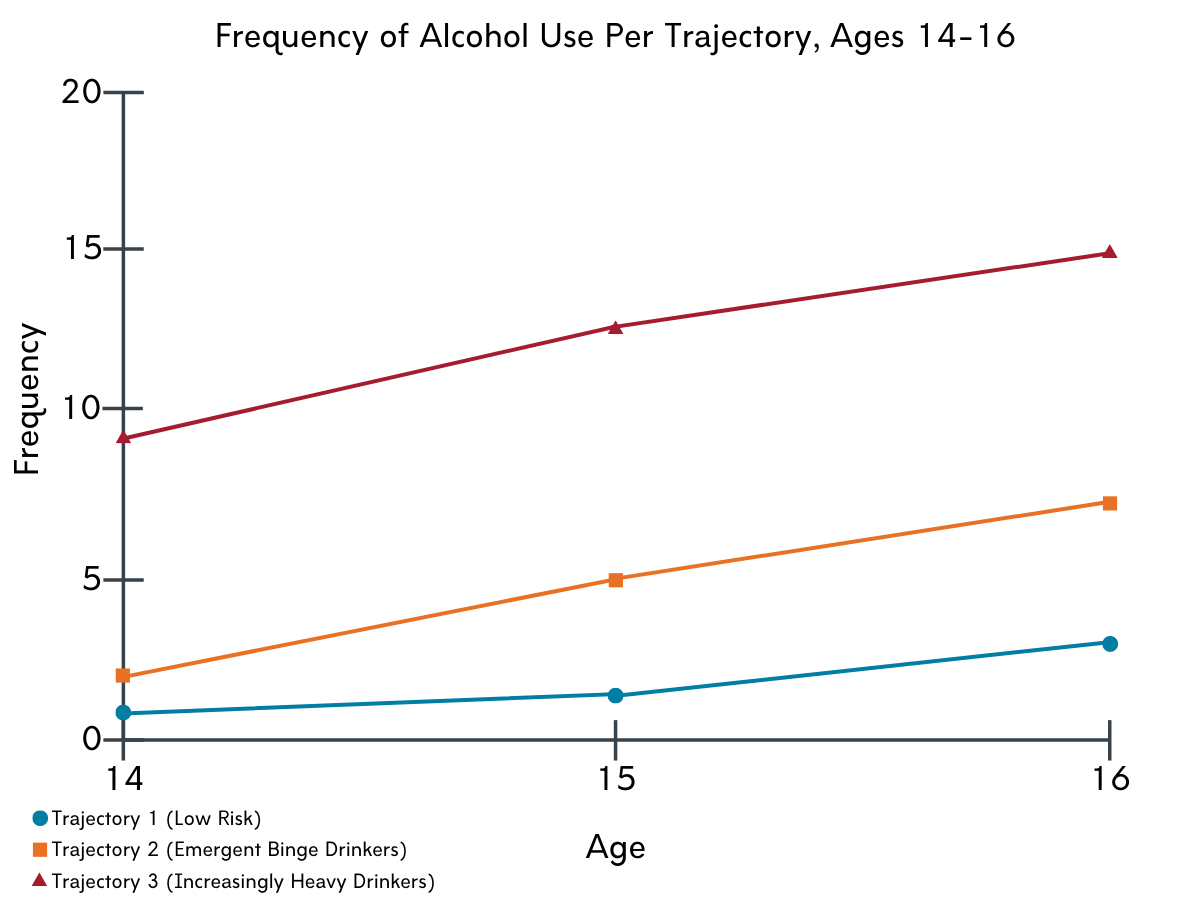

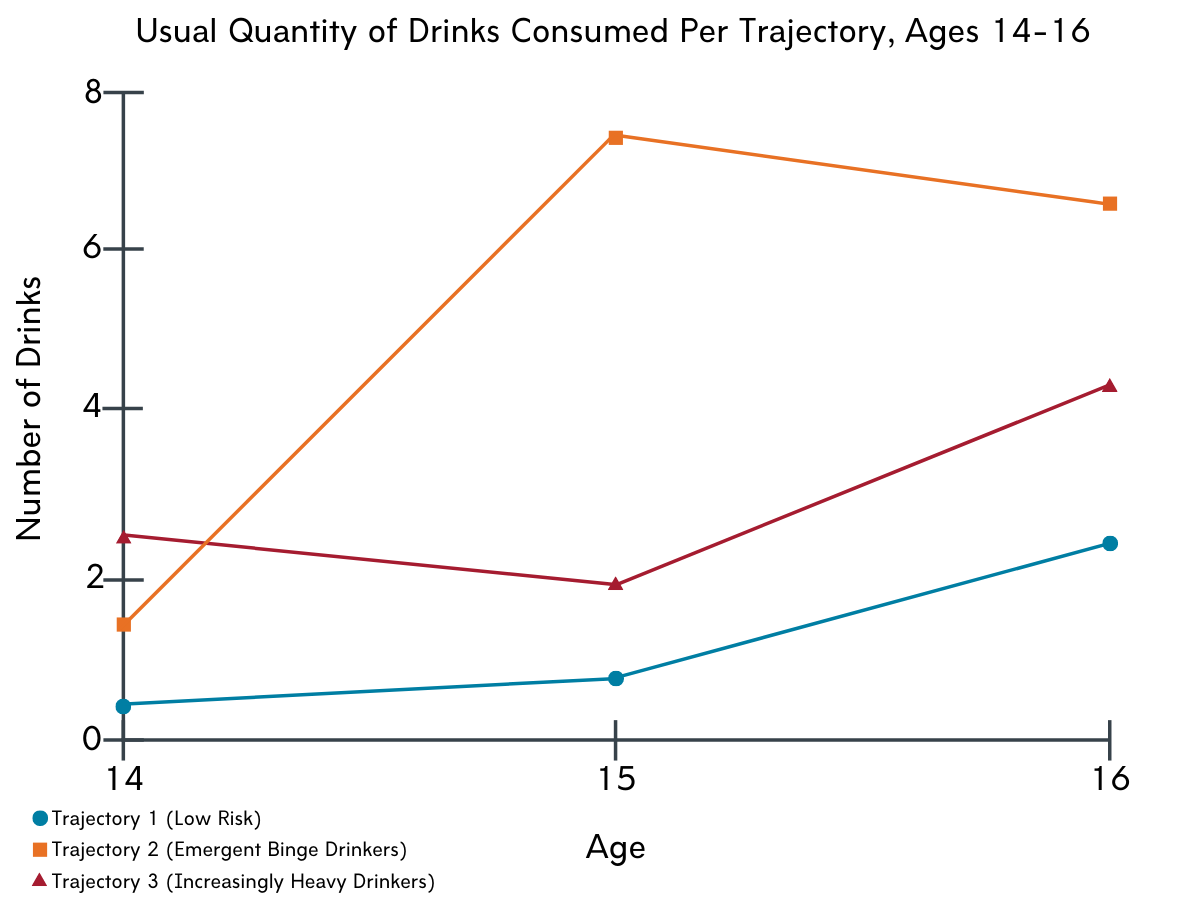

Of all the adolescents in the sample, 878 were Low Risk Drinkers, 65 were Emergent Binge Drinkers, and 51 were Increasingly Heavy Drinkers. Emergent Binge Drinkers showed a significant increase in the number of drinks consumed on a typical drinking occasion from age 14 to age 15 with a slight decrease at age 16. Increasingly Heavy Drinkers had a much lower quantity of drinks consumed on a typical drinking occasion than Emergent Binge Drinkers at age 15 and 16 but had a higher frequency of alcohol use at ages 14, 15, and 16.

Figures 1 and 2. Frequency of alcohol use and usual quantity of drinks consumed compared across time for all three trajectories.

Several variables predicted classification into each adolescent drinking class.

Compared with the low-risk group, the high-risk groups were more likely to be from families of lower socioeconomic status, had higher scores for novelty seeking, higher levels of conduct problems, were more likely to report family problems, and had parental attitudes that were more positive towards drinking and more permissive towards adolescent drinking. Regarding differences between the two high-risk drinking groups, Emergent Binge Drinkers were more likely to have had a parent with a history of alcohol problems and Increasingly Heavy Drinkers were more likely to have had a history of penetrative sexual abuse.

Alcohol-related outcomes in adulthood were different among the three classes.

The three groups of adolescent drinkers were followed into early adulthood, where alcohol-related outcomes were pooled from ages 18-35. Increasingly Heavy Drinkers had a greater percentage of people with alcohol use disorder compared with the low-risk group, and both high-risk drinking groups had a higher number of alcohol use disorder symptoms compared with the low-risk group. Increasingly Heavy Drinkers had a much higher amount of alcohol consumed than Emergent Binge Drinkers and Low Risk Drinkers.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study identified three groups of adolescents with differing patterns of alcohol use. Of the two high-risk groups, Increasingly Heavy Drinkers used alcohol more frequently, whereas Emergent Binge Drinkers consumed more alcohol on a typical drinking occasion. In addition, these groups differed by associated childhood variables and drinking trajectories into early adulthood.

While it is difficult to know exactly why the two high-risk drinking groups demonstrated different drinking patterns, it is possible that they have different factors that drive their drinking. Emergent Binge Drinkers may be mimicking their parents’ drinking behavior via social learning models, drinking heavily though less frequently. Increasingly Heavy Drinkers, on the other hand, may be using alcohol as a coping mechanism secondary to trauma and other adverse childhood experiences, and, due to the nature of spreading out high volumes of alcohol over frequent drinking episodes as a means to cope in the likely context of low tolerance, may draw less attention to their drinking habits than Emergent Binge Drinkers. In other words, the dose of alcohol needed to cope for Increasingly Heavy Drinkers may initially be low as tolerance may not have developed early in the progression of continuous drinking, but with increased alcohol consumption needed over time to cope as tolerance increases. While there is reason to be particularly concerned about Increasingly Heavy Drinkers given that drinking to cope in young adults is associated with more negative consequences, there is also reason for optimism. Early intervention in this population holds promise in mitigating the risk for developing problems later in life. In fact, at least some research shows that adolescents and emerging adults who are drinking to cope are more likely to show a positive response to treatment compared to those drinking for other motives. As outlined in a prior RRI Bulletin summary, screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment, or SBIRT, in pediatric primary care settings is one way to detect and and treat adolescent substance use problems as early as possible.

The implications of these findings are that tailoring interventions to address specific risk factors for developing alcohol problems may be the most appropriate response to prevent and intervene with adolescent drinking. Typically, alcohol policies and prevention strategies directed at adolescents are either blanketed to this entire population or targeted towards high-risk youth. This study provides insight that there may be different groups, or phenotypes, of high-risk adolescent drinkers. Emergent Binge Drinkers may respond to policy approaches aimed at reducing access and exposure as well as interventions that address parental attitudes toward alcohol. Increasingly Heavy Drinkers may benefit from early interventions that identify and treat conditions that are associated with self-medicating using alcohol, such as a history of trauma.

These types of tailored intervention efforts are common among adults with alcohol use disorder, where, for example, those who drink primarily for rewarding effects rather than to reduce negative feelings responded better to the medication naltrexone than acamprosate. Importantly, though, studies that find support for an individualized intervention effect after the fact often do not support such an approach when researchers hypothesize and test these individualized intervention effects from the outset. Thus, while this study does suggest a potentially useful approach that tailors adolescent drinking prevention and intervention strategies based on a series of psychosocial factors, such intervention approaches must be tested out empirically before widespread implementation to maximize its chances of having a broad impact and being cost-effective.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Alcohol use is strongly tied to a society’s culture. This study took place in New Zealand, so the findings may not generalize to other countries like the United States.

- The two groups identified as risky drinkers (Emergent Binge Drinkers and Increasingly Heavy Drinkers) had small sample sizes. This made it difficult statistically for the authors to be able to detect differences between the groups (i.e., statistical power) for both the model that predicts trajectories of problematic drinking in adulthood and the model that identifies associated risk factors. It is possible that there were other meaningful differences between the three groups that were not identified.

- The rate at which participants drop out of the study over time (i.e., attrition) can be problematic in a longitudinal study because those who drop out of the study may be very different from those that remain in the study, leading to bias of the results. A statistical approach is used on the birth cohort to minimize this type of bias.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study identified three groups of adolescents with differing patterns of alcohol use: Low Risk Drinkers, Emergent Binge Drinkers, and Increasingly Heavy Drinkers. The risky drinking groups demonstrated more alcohol problems as adults. While both risky drinking groups had more accepting parental attitudes regarding alcohol compared with Low Risk Drinkers, Emergent Binge Drinkers had a stronger family history of alcohol problems and Increasingly Heavy Drinkers were more likely to have experienced sexual abuse in childhood. This study suggests that unaddressed trauma may have an impact on subsequent problematic alcohol use at least for some. In addition, families should be aware that permissive attitudes toward adolescent drinking and positive attitudes toward drinking alcohol in general can be influential to other family members. This effect may be particularly influential among parents and children.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study identified three groups of adolescents, ages 14-16, with differing patterns of alcohol use: Low Risk Drinkers, Emergent Binge Drinkers, and Increasingly Heavy Drinkers. Of the two high-risk groups, Increasingly Heavy Drinkers used alcohol more frequently whereas Emergent Binge Drinkers consumed more alcohol on a typical drinking occasion. Both risky drinking groups demonstrated more alcohol problems as adults compared to Low Risk Drinkers, although childhood variables associated with these groups suggest that Emergent Binge Drinkers may have modelled parental behavior while Increasingly Heavy Drinkers may have been drinking to cope. As a clinician, it may be helpful to assess drinking patterns and social factors in adolescents with problematic alcohol use. While findings from this study are not sufficient to inform targeted practice changes, its approach highlights the potential for individualized care based on behavioral, personality, and family-related factors.

- For scientists: This study used latent class analysis that identified three groups of adolescents, ages 14-16, with differing patterns of alcohol use: Low Risk Drinkers, Emergent Binge Drinkers, and Increasingly Heavy Drinkers. Of the two high-risk groups, Increasingly Heavy Drinkers used alcohol more frequently whereas Emergent Binge Drinkers consumed more alcohol on a typical drinking occasion. Both risky drinking groups demonstrated more alcohol problems as adults compared to Low Risk Drinkers measured by prevalence of alcohol use disorder, number of alcohol use disorder symptoms, and amount of alcohol consumption, although childhood variables associated with these groups suggest that Emergent Binge Drinkers may have modelled parental behavior while Increasingly Heavy Drinkers may have been drinking to cope. Generalizability could be a major limitation in this study, as alcohol consumption culture in New Zealand may be much different than other countries. This is an interesting finding, though the sample sizes of the high-risk groups are small, that may have potential if replicated in other countries with a larger sample size. Although cohort studies can be an expensive endeavor, replicating this study using an existing established cohort could be promising given that alcohol is the third leading cause of preventable death in the U.S.

- For policy makers: This study identified three groups of adolescents with differing patterns of alcohol use: Low Risk Drinkers, Emergent Binge Drinkers, and Increasingly Heavy Drinkers. Of the two high-risk groups, Increasingly Heavy Drinkers used alcohol more frequently whereas Emergent Binge Drinkers consumed more alcohol on a typical drinking occasion. Both risky drinking groups demonstrated more alcohol problems as adults compared to Low Risk Drinkers, although childhood variables associated with these groups suggest that Emergent Binge Drinkers may have modelled parental behavior while Increasingly Heavy Drinkers may have been drinking to cope. These findings suggest that one policy response to adolescents that show signs of excessive alcohol use may be inadequate. Although a study finding in New Zealand could look much different in another country and concrete recommendations cannot be made, the possibility of more than one high-risk adolescent group should be considered for policies addressing the availability of alcohol as well as other prevention strategies.

CITATIONS

Boden, J. M., Newton-Howes, G., Foulds, J., Spittlehouse, J., & Cook, S. (2019). Trajectories of alcohol use problems based on early adolescent alcohol use: Findings from a 35 year population cohort. International Journal of Drug Policy, 74, 18-25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.06.011