Older adults with mood and anxiety disorders benefit as much from alcohol use disorder treatment as those without these co-occurring conditions

Individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs) commonly experience other mental health conditions, such as depression or anxiety, and many do not receive treatment. People with co-occurring conditions may be less likely to complete treatment and have poorer treatment outcomes. However, little is known about the role of co-occurring depression and anxiety in alcohol use treatment outcomes among older adults. This study explored this question in older adults receiving treatment for alcohol use in Germany, Denmark, and the U.S.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, are very common among individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). Nearly 40% of people with SUDs have another mental health condition, including 16-28% with a mood disorder and 16-24% with an anxiety disorder. Rates of receiving treatment are low among people with co-occurring disorders, with about half receiving treatment in the past year. While individuals with co-occurring conditions appear to be more likely to receive treatment than individuals with mental health disorders or SUDs alone, some studies have found that treatment outcomes are poorer among adults with co-occurring conditions and that they may be less likely to complete treatment. Compared with younger adults, older adults may face additional complications from problematic alcohol use, such as dangerous interactions with medications, falls that result in injury, and exacerbation of underlying medical conditions. Older adults may benefit from longer-term treatment for SUD. However, little research has examined the role of comorbid depression and anxiety in alcohol use treatment outcomes in older adults. In this study, the research team examined whether co-occurring anxiety or depression disorders affected drinking outcomes in a multinational sample of older adults receiving treatment for alcohol use disorders. The study examined whether this effect differed depending on the length of treatment (4 sessions vs. 12 sessions), with the longer treatment including additional cognitive-behavioral skills training.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial conducted in Denmark, the US, and Germany, which tested two psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorder (AUD) in 693 older adults (age 60+, average age = 65.5) who were followed up at one, three, and six months after the baseline assessment. Study participants were included if they had current AUD and were excluded if they had severe mental health problems (including psychosis, bipolar disorder, severe depression, or current suicidal thoughts) or if they misused opioids or stimulants. As such, the study focused on individuals with alcohol, but not other drug use disorders, who also had non-severe co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two treatment conditions:

- Four sessions of motivational enhancement therapy

- Four sessions of motivational enhancement therapy plus up to eight sessions of a community reinforcement approach that was adapted for older adults

The research team examined the impact of any mental health disorder, any mood disorder, and any anxiety disorder on alcohol-related outcomes at baseline, and at 1, 3, and 6 months after baseline. The presence of mental health disorders was determined with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) version 5.0. Outcomes included:

- Number of drinks per day

- Heavy episodic drinking: More than two drinks in one day for women; more than three drinks in one day for men

- Hazardous alcohol use: Having a daily average of more than one drink per day for women or more than two drinks per day for men

The research team also examined whether the relationship between the presence of mental health disorder variables and the alcohol-related outcomes was different across the two treatment conditions (motivational enhancement alone vs. motivational enhancement plus community reinforcement).

The researchers controlled for age, gender, and country in all of their analyses. The sample was 61% male, 63% retired, and 48% married, and most participants (82%) had at least 10 years of education.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Before treatment, older adults with co-occurring disorders consumed more alcohol than those without co-occurring conditions.

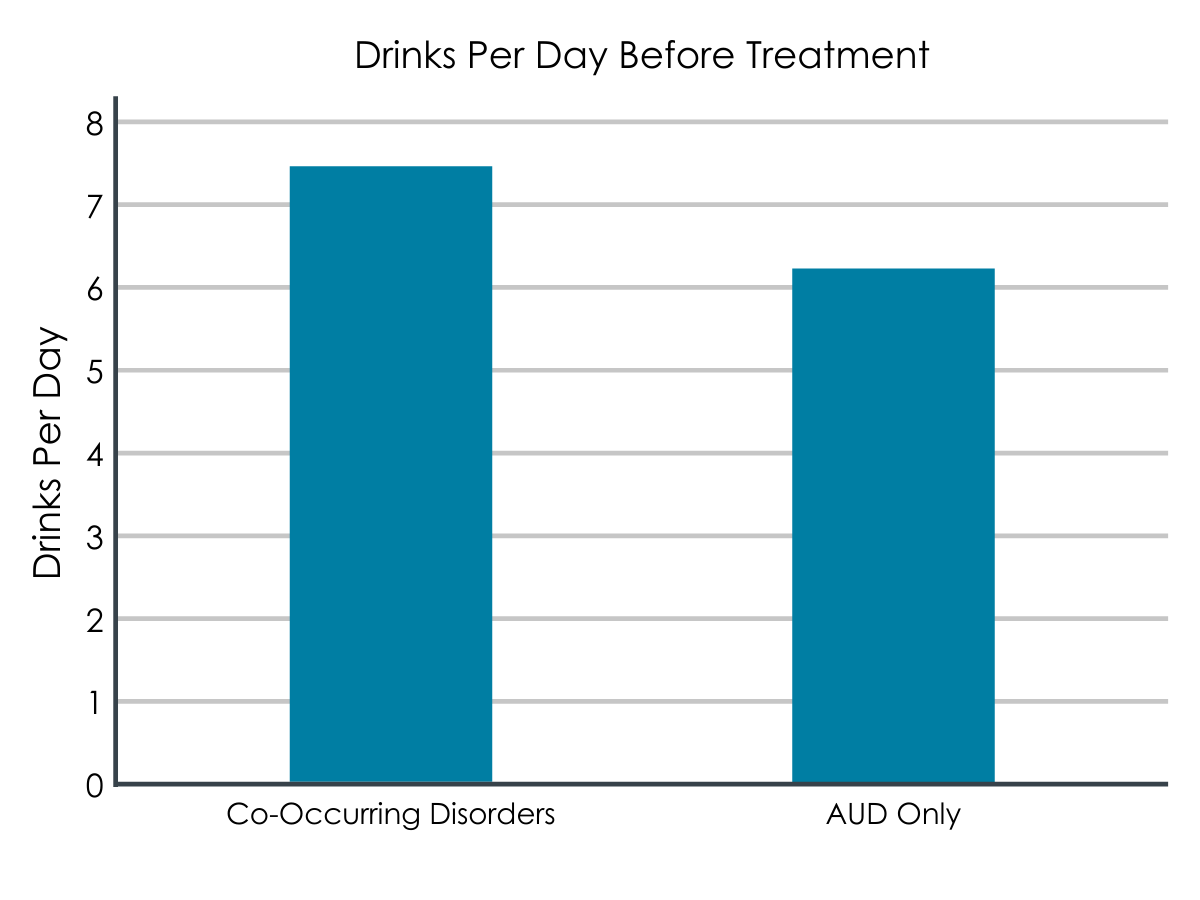

In this sample of older adults with AUD, most reported hazardous alcohol use (87%) and heavy episodic drinking (96%). Nearly one in five (17%) had another current mental health condition, including 12% with a mood disorder and 8% with an anxiety disorder. Thus, some individuals had both a mood and an anxiety disorder. Before treatment, those with a co-occurring disorder drank more per day (7.5 drinks per day) than those without (6.2 drinks/day).

Figure 1. The standard deviation (SD) for Co-Occurring Disorders was 6.1, while the SD for AUD Only was 4.8. Standard deviation indicates the amount of variance between values for each member of the study population, with a higher SD indicating more variance. This means that there is a wider range of drinks per day for members of the Co-Occurring Disorders group, with the mean ultimately coming to 7.5, while the AUD Group range was a bit closer to its mean of 6.2.

Alcohol-related outcomes improved substantially during and following treatment, with greater improvements following longer treatment.

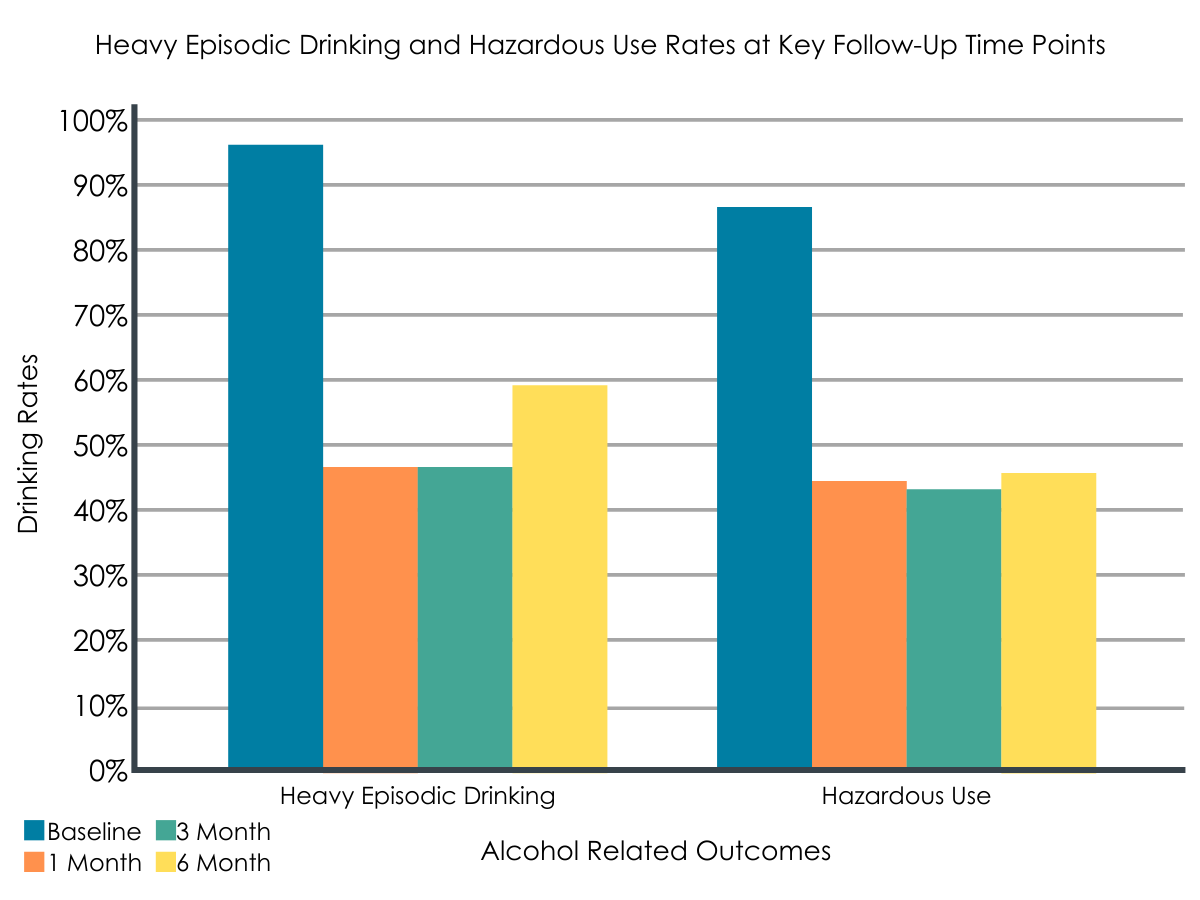

Rates of heavy episodic drinking decreased from 96% before treatment to 47% at 1 month after baseline, 47% at 3 months, and 59% at 6 months. Rates of hazardous alcohol use fell from 87% before treatment to 44% at 1 month, 43% at 3 months, and 46% at 6 months. Drinks per day decreased from 6.4 drinks per day at baseline to 2.5 drinks per day at 1 month, 2.3 at 3 months and 2.6 at 6 months. Compared to older adults who received motivational enhancement alone (4 sessions), older adults who received motivational enhancement plus community reinforcement (12 sessions) improved more on all of these outcomes between baseline and 3-month follow-up, though there were no treatment differences at the 6-month follow-up.

Figure 2.

The impact of co-occurring disorders on outcomes was limited, with some exceptions.

The presence of any mental health disorder, mood disorder, or anxiety disorder did not influence the improvement over time for most of the alcohol-related outcomes. One exception was that individuals with mood disorders were more likely to report hazardous alcohol use at baseline (before treatment) and showed greater decreases in hazardous alcohol use at 3- and 6-months post-baseline. Similarly, individuals with mood disorders reported more drinks per day at baseline and a greater reduction in drinks per day at 1 and 6 months. In the shorter treatment condition only, individuals with anxiety disorders showed a smaller reduction in drinking-related outcomes compared to individuals without anxiety disorders at 1 and 3 months. Those with and without an anxiety disorder benefitted similarly from the motivational enhancement plus community reinforcement treatment, though.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study examined alcohol-related outcomes (hazardous drinking, heavy episodic drinking, and drinks per day) during and following treatment in older adults with and without co-occurring mental health conditions. Few prior studies have researched this population, despite growing numbers of older adults being treated for SUD and despite unique vulnerabilities faced by this population.

Prior research has identified having another mental health condition as a risk factor for substance use later in life, and noted higher rates of co-occurring conditions among older adults who drink more. In a nationally-representative study, older adults whose drinking was classified as high-risk were more likely to have major depression and anxiety disorders than older adults who drank at low-risk or moderate-risk levels (for depression: 24.9% vs. 3.2% and 3.2%, respectively; for anxiety: 8.8%, 1.4% and 2.3%, respectively). The older adults in the study reviewed here had similarly elevated rates of co-occurring conditions (17% with any co-occurring condition, 12% with depression, and 8% with anxiety). Furthermore, those with a co-occurring condition reported more drinks per day when entering treatment than those without a co-occurring condition.

Older adults in this study, all of whom had AUD, improved substantially during and following treatment in alcohol-related outcomes. However, those who received motivational enhancement therapy plus community reinforcement (12 sessions) showed greater improvements compared to motivational enhancement only (4 sessions). This finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that motivational interventions are effective for people with co-occurring alcohol use, depression, and anxiety, with longer interventions producing better outcomes. Very little research exists on treatment interventions specifically for older adults with substance-related problems. Therefore, this study fills an important gap by showing that older adults can improve in as little as four weeks of treatment, but that greater improvements may be gained by providing a longer-term (i.e., 12 session) treatment with additional training in cognitive-behavioral skills.

With few exceptions, older adults with AUD and co-occurring mental health conditions improved just as much during and following treatment as older adults with AUD who did not have co-occurring conditions. The findings that individuals with mood disorders showed greater reductions in hazardous alcohol use and drinks per day over time may reflect the fact that they reported higher levels of hazardous alcohol use and drinks per day before the start of treatment. In other words, they may have had more room for improvement because of their higher starting point. Similarly, the smaller improvements shown by individuals with anxiety disorders who received the shorter treatment may have emerged because those without anxiety disorders consumed more alcohol at baseline (i.e., had more room for improvement). These findings are encouraging because they suggest that, for older adults, having a co-occurring mood or anxiety disorder need not be an impediment to benefitting from treatment for AUD. This is particularly important considering the many barriers that exist to getting treatment for SUD and/or mental health conditions.

It is important to note that individuals were excluded from this study if they had certain types of co-occurring conditions, such as psychotic symptoms, severe depression, bipolar disorder, or current suicidal thoughts or behaviors. As a result, the co-occurring disorders that were included in this study were on the less severe end of the spectrum. Prior research with young adults has also found that those with co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders benefitted as much from residential treatment as those without co-occurring conditions. When co-occurring mental health conditions are less impairing, it may be possible for SUD-focused treatments to routinely address mental health symptoms through skills for reducing or eliminating substance use. For example, cognitive-behavioral SUD interventions often include training on examining internal triggers (e.g., depressed mood, anxiety) for substance use and developing coping skills for those triggers. Also, alcohol use can worsen depression and anxiety symptoms so abstinence or reductions in alcohol use often results in corollary improvements in mood and anxiety. When co-occurring conditions are more severe, however, this indirect focus on mental health symptoms may be insufficient. With more serious co-occurring conditions, such as psychotic disorders, it is often important to integrate treatment approaches (both psychosocial and medications) for SUD and mental health. Individuals with serious mental illnesses may have deficits in social or executive functioning that would reduce their ability to benefit from motivational or community approaches like those used in this study.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Individuals were excluded from the sample for having certain types of co-occurring conditions, such as psychotic symptoms, severe depression, bipolar disorder, or current suicidal thoughts or behaviors. As a result, the findings of this study may not apply to older adults with these more severe mental health conditions.

- Individuals were excluded from the sample if they also used opioids or stimulants. Use or misuse of other substances, such as cannabis, was not reported. As a result, the findings of this study may not apply to older adults who use multiple substances, rather than alcohol alone.

- This study examined alcohol-related outcomes only, and did not examine whether or how individuals’ symptoms of depression, anxiety, or other mental health conditions changed over time. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether older adults experienced improvements in these symptoms during or following treatment for AUD.

- No information was provided about how many of the possible 4 or 12 treatment sessions participants attended. While there appeared to be a benefit of the longer-term treatment, it would be useful to know how many treatment sessions were actually attended in each condition.

BOTTOM LINE

This study examined alcohol-related outcomes (hazardous drinking, heavy episodic drinking, and drinks per day) during and following treatment in 693 older adults with (17%) and without (83%) non-severe co-occurring mental health conditions. Older adults received either a 4-session motivational enhancement treatment or a 12-session motivational enhancement plus community reinforcement treatment focused on reducing alcohol use. The study found that participants in both treatment conditions improved during and after treatment, with those in the longer treatment showing greater improvements. In general, individuals with co-occurring mental health conditions benefitted from treatment just as much as individuals without co-occurring conditions.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Research on effective treatments for older adults with co-occurring substance use and mental health problems is limited, but the results of this study are encouraging. Individuals and families seeking recovery can take comfort in knowing that older adults can benefit from relatively short-term treatment (1-3 months) and that having co-occurring depression or anxiety does not prevent older adults from benefitting from treatment for alcohol-related problems.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Older adults with co-occurring conditions face unique challenges in treatment, and very little research exists on which treatments are the most effective for this population. Clinicians should not assume that older adults with non-severe co-occurring conditions, such as depressive or anxiety disorders, cannot benefit from treatment for alcohol-related problems, even if they enter treatment with more severe alcohol use. In fact, that may lead to greater improvements during treatment, as found in this study. Clinicians and treatment systems will likely need to be prepared for an increase in older adult patients as the population continues to age, including being knowledgeable about the particular vulnerabilities affecting older adults with substance- and mental health-related issues.

- For scientists: This study stands out for being a randomized clinical trial of alcohol-related outcomes in a large, multinational sample of older adults; such studies have been rare in older adult populations. Even fewer studies have examined whether co-occurring mental health conditions affect AUD treatment outcomes in this population, making the results of this study very valuable. Nevertheless, further research on the efficacy of various treatments for this population is essential, including trials of integrated substance use and mental health treatments and studies that examine changes in mental health symptoms over time. It will be important to study samples of older adults with more severe mental health problems, as those individuals were excluded from the present study.

- For policy makers: This study is one of few to compare treatments for older adults with and without co-occurring substance use and mental health conditions. With an aging population worldwide, and substance use and mental health conditions persisting into old age for many people, it is perhaps more important than ever for public health to fund research on effective treatments for this population. It is essential that policy makers fund training programs designed to increase clinicians’ competency with working with older adults with co-occurring conditions.

CITATIONS

Behrendt, S., Kuerbis, A., Bilberg, R., Braun-Michl, B., Mejldal, A., Bühringer, G., Bogenschutz, M., Andersen, K., & Nielsen, A. S. (2020). Impact of comorbid mental disorders on outcomes of brief outpatient treatment for DSM-5 alcohol use disorder in older adults. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 119, 108143. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108143