Individuals can get help for alcohol use and posttraumatic stress disorders at the same time: A movement toward integrated treatment approaches

Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are at increased risk of having co-occurring alcohol use disorder. However, it is not known whether the first-line treatment for PTSD (i.e., prolonged exposure therapy) is also effective in reducing problematic drinking. This study replicated prior findings suggesting prolonged exposure therapy is superior in treating PTSD symptoms, but was not more effective in reducing heavy drinking days than an intervention intended primarily to increase coping skills. However, findings from this study do challenge the notion that alcohol use disorder may be a barrier to receiving gold-standard treatment for PTSD.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

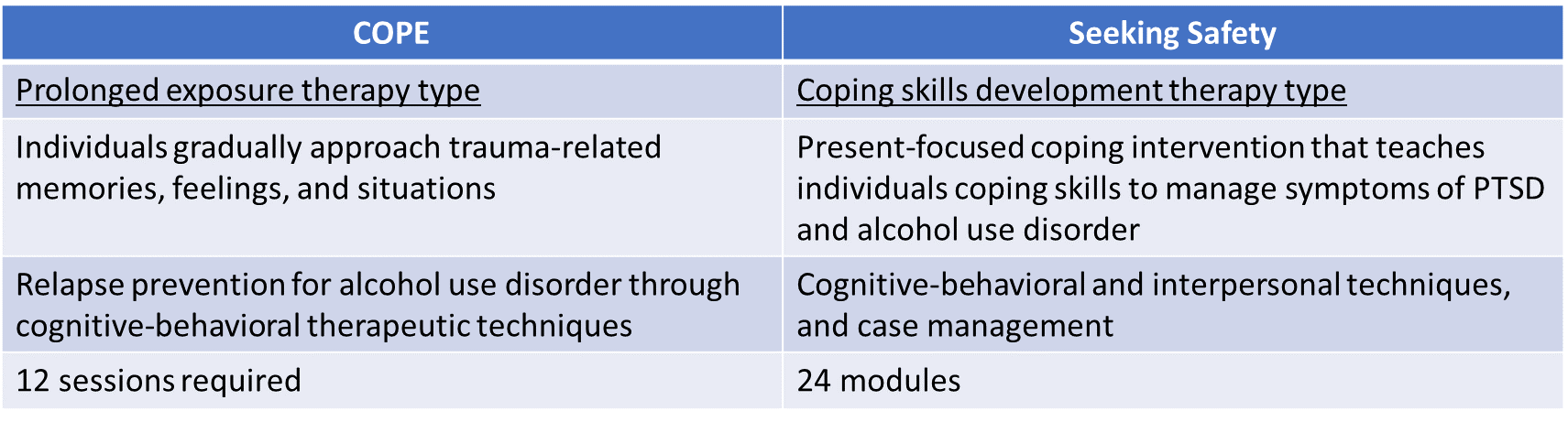

Individuals with PTSD are more likely to have an alcohol use disorder than individuals in the general population. One representative survey of adults in the United States found individuals with PTSD were 1.2 times as likely to have an alcohol use disorder in their lifetime than those without PTSD. PTSD is also associated with a more problematic course of alcohol use, including greater difficulty quitting, briefer abstinence periods, and more associated medical, legal, and psychological consequences. These disparities in alcohol use outcomes in individuals with PTSD underscore the need to identify treatments that are effective in treating both symptoms of PTSD as well as problematic alcohol use. To address this need, Norman and colleagues studied the immediate, 3-month, and 6-month outcomes among 119 adult veterans with co-occurring PTSD and alcohol use disorder who received one of two competing treatment approaches. The table below outlines key components of each treatment approach. The first treatment, called Concurrent Treatment for PTSD and Substance Use Disorder Using Prolonged Exposure, or “COPE,” was integrated with prolonged exposure therapy that involves 1) helping individuals gradually approach trauma-related memories, feelings, and situations, and 2) relapse prevention for alcohol use disorder using cognitive and behavioral therapeutic techniques. The second tested treatment, called Seeking Safety (an empirically-supported treatment for co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorder), was a present-focused coping intervention that aimed to teach individuals skills to cope with both symptoms of PTSD and alcohol use disorder. The ultimate goal of this research study was to determine which treatment modality was most effective in supporting the recovery of individuals living with both PTSD and alcohol use disorder.

Figure 1. Chart comparing the features of both the COPE and Seeking Safety treatment approaches, including general timeframe of treatment, and specific therapy techniques.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Study authors examined 119 adult veterans (90% male, average age of 41 years, 66% White) with current symptoms of PTSD who were receiving care at the San Diego Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). While individuals were encouraged to avoid other treatment for their PTSD, they were able to receive standard mental health treatment at the VA while participating in this study. For example, 65% were taking psychotropic medication during the study. Participants also needed to have current alcohol use disorder, at least 20 days of heavy alcohol use (see below for heavy drinking definition) in the past three months, and a stated desire to quit or cut back on alcohol use. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either 12-16 90-minute sessions of COPE (i.e., integrated prolonged exposure therapy) or Seeking Safety (i.e., coping skills–focused therapy). Sessions were administered preferably once to twice per week on consecutive weeks, but could span across a 6-month period of time.

Participants completed assessments of PTSD symptoms and problematic drinking behavior after treatment and at 3- and 6-months posttreatment, and these assessments were administered by study staff who were not aware of (i.e., “blinded” to) the treatment received. The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) was the primary measure used to quantify PTSD symptoms and diagnosis, with scores >=12 suggestive of a PTSD diagnosis (range: 0-80). Frequency and quantity of alcohol use were ascertained via a calendar-based interview (i.e., Timeline Follow-Back), which was used to deduce A) the percent of heavy drinking days defined as the number of days in which 5 or more drinks for men or 4 or more drinks for women were consumed since the last assessment, and B) percent days abstinent for alcohol. A breathalyzer was administered to any participant who appeared intoxicated.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

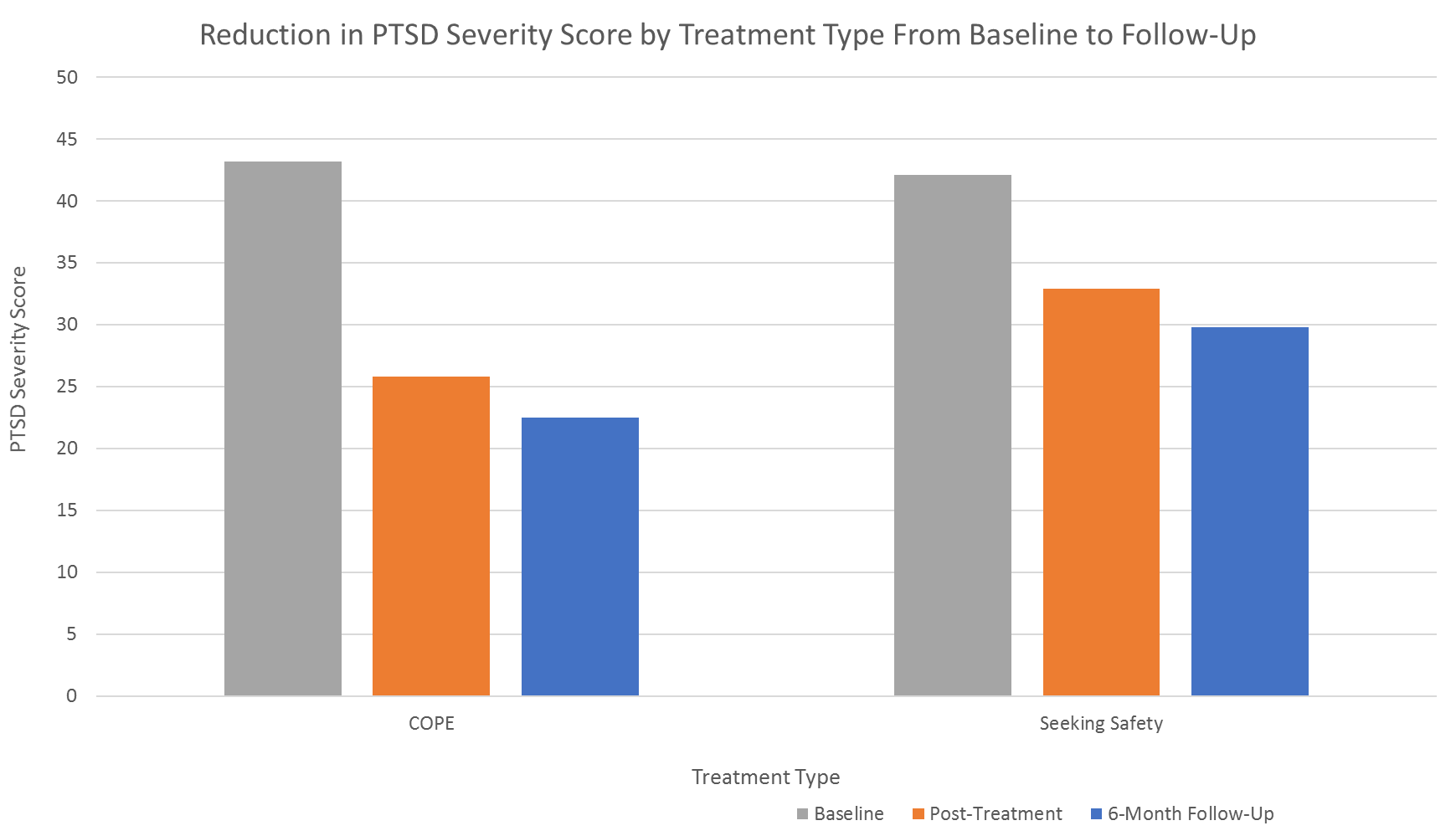

PTSD symptoms declined more in veterans who received integrated prolonged exposure therapy compared to the present-focused coping intervention.

PTSD symptoms improved over time regardless of therapy assignment; however, the COPE group improved more than did the Seeking Safety group. Immediately after treatment, over 20% of individuals went from having a PTSD diagnosis to no longer meeting criteria for the condition (“remission”), compared to only 7% in the present-focused coping intervention. The advantage for the COPE group became slightly weakened over time but was nevertheless maintained; the greater PTSD symptom gains for the COPE group were still present 6 months after completing treatment.

Figure 2.

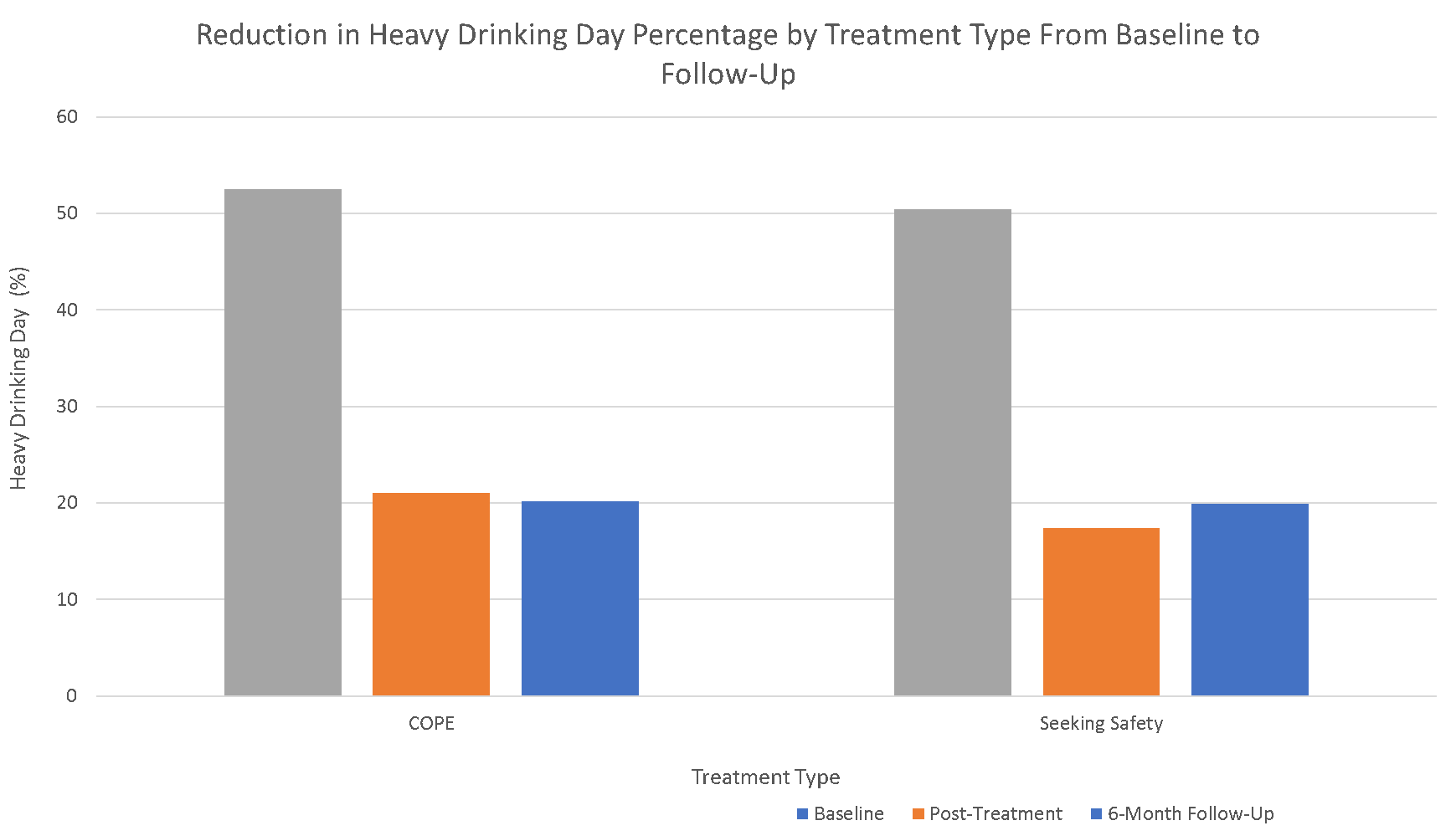

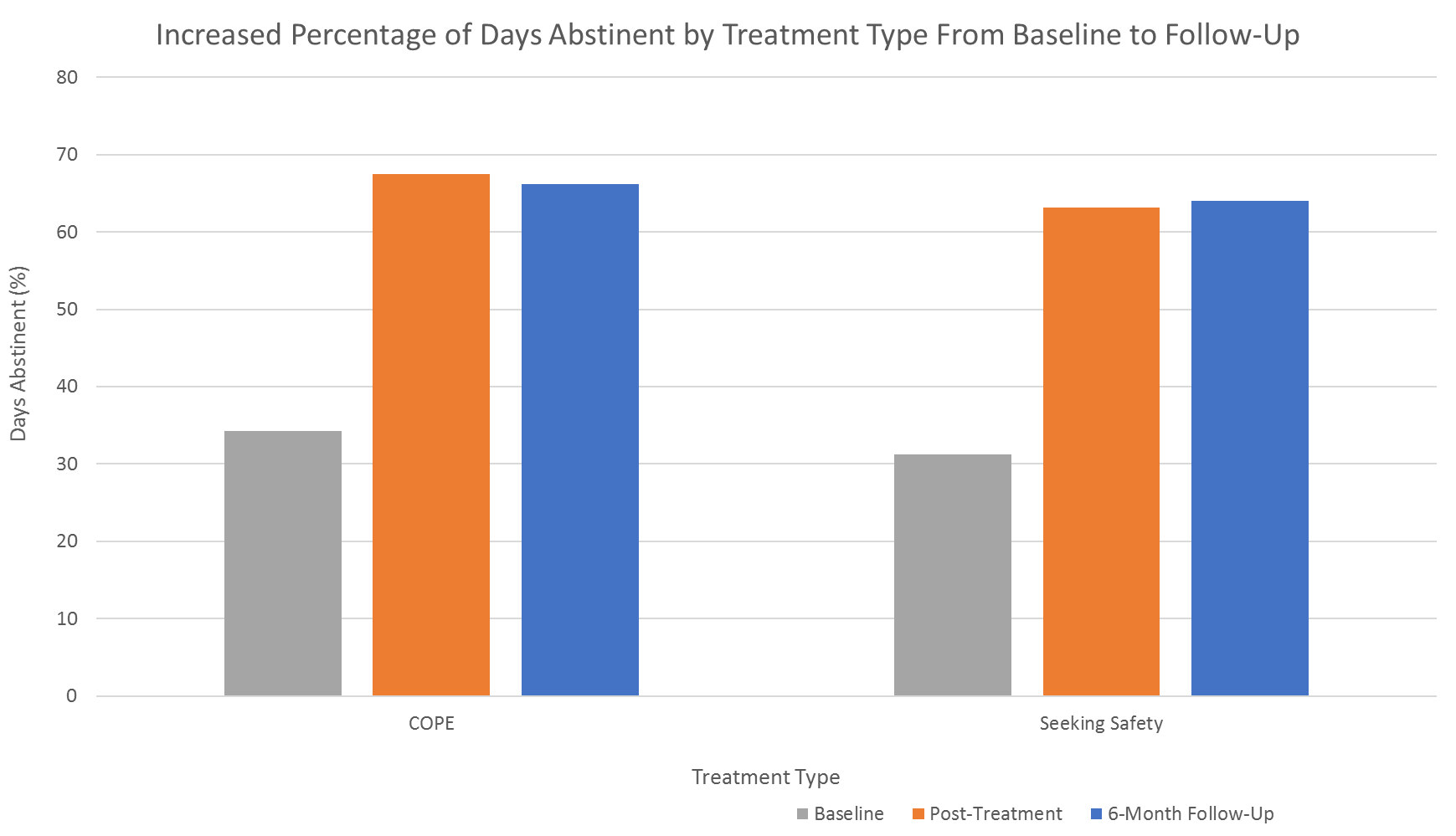

Drinking outcomes improved similarly across treatment groups.

All participants showed reductions in the percent of heavy drinking days over time, though the extent of decrease was similar in those who received integrated prolonged exposure and the present-focused coping intervention. Findings were similar – both groups displayed similarly improved drinking – when the outcome was percent days abstinent as well.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study is responsive to the urgent need to identify treatments that are effective in mitigating both symptoms of PTSD and alcohol use disorder, the co-occurrence of which is both highly common and linked with greater negative outcomes compared to either disorder alone. Findings from this study build upon a robust literature suggesting that prolonged exposure therapy is the gold standard for mitigating PTSD symptoms. Importantly, this study demonstrates that prolonged exposure therapy is effective even among individuals with an active alcohol use disorder. This study, plus a growing body of literature, challenges a commonly held belief that individuals with alcohol use disorder cannot tolerate exposure-based approaches, addressing the notion of alcohol use disorder as a potential barrier to receiving widely–supported, evidence–based therapy for PTSD.

Contrary to the authors’ hypotheses, however, prolonged exposure therapy was no more effective in reducing problematic alcohol use than the present-focused coping intervention. The fact that this PTSD reduction benefit did not translate into lower problematic alcohol use suggests that, whereas some PTSD patients may have initially drunk (and still drink) alcohol to help “medicate” the distress caused by PTSD, for many others, the alcohol use may persist fairly independently of PTSD. Although group differences were not found with regard to drinking use, it is notable that both groups showed significant reductions in drinking over time, suggesting that simultaneous treatment for alcohol use disorder can be integrated into the framework of PTSD treatment without interfering with the treatment of PTSD itself. Future studies are needed to determine which PTSD treatment modalities may have the most beneficial impact on drinking behaviors. Some findings from other groups provide promising preliminary support for approaches that involve teaching individuals to challenge and modify maladaptive beliefs (cognitive processing therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy) and guided eye movements with the goal of diminishing negative feelings associated with traumatic events (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study involved military veterans and participants were mostly men (90%). Although this is not uncommon for studies involving veterans, particularly those recruited from VA settings, the limited representation of women suggests it is unclear if findings also apply to women.

- There was a non-negligible dropout rate, with approximately 26% of the baseline sample not providing data at the follow-up assessments. Additionally, dropout was higher in the COPE intervention (33% dropout) compared to the Seeking Safety intervention (18% dropout), raising the possibility that individuals dropped out of treatment because they found the experience aversive or ineffective. Although authors statistically controlled for dropout, findings may not extend to all individuals at baseline, but rather to the “treatment responders.”

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study demonstrated that the simultaneous attention to both PTSD symptoms and alcohol use disorder is possible, and attention to both disorders in an integrated treatment approach is linked with improved functioning. Therefore, patients with both conditions should feel empowered to have both PTSD symptoms and problematic drinking behavior as treatment targets that can be addressed in tandem rather than in parallel. This is comparable to other studies that find integrated approaches to be successful in cases of co-occurring substance use and other neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression and ADHD.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Patients with PTSD and alcohol use disorder benefitted from integrated treatment approaches. Findings suggest that individuals with comorbid PTSD and alcohol use disorder should not be excluded from receiving front-line PTSD treatment on account of their untreated alcohol use. Rather, alcohol use should be identified as a core treatment target and addressed in tandem with PTSD. Further work is needed, though, to determine the most effective treatment modality for addressing problematic alcohol use in the context of PTSD.

- For scientists: Findings point to the efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy, even in the presence of co-occurring alcohol use, in mitigating symptoms of PTSD. While findings suggest a reduction in heavy drinking days, this effect was not specific to the therapeutic approach of prolonged exposure therapy. This finding does not align with “self-medication” as a maintaining condition for alcohol use disorder, at least for some. While more work is needed to determine the most effective approach for reducing alcohol use among PTSD patients, this study represents an important first step in decreasing barriers to access to empirically-validated and integrated treatments. Additionally, while prolonged exposure therapy is commonly viewed as a gold standard approach for trauma treatment, retention particularly in real-world settings is often low. Co-occurring substance use has been found to be one patient factor robustly associated with dropout. Therefore, future studies aimed at enhancing engagement and retention, especially among patients with co-occurring disorders, is critical for the widespread dissemination of this approach.

- For policy makers: Findings lend preliminary support for the efficacy of integrated treatment approaches, which runs contrary to the outdated, yet still pervasively present notion, that substance use disorders need to be fully remitted prior to the treatment of co-occurring other mental health concerns (e.g., PTSD, depression, anxiety disorders). Integrated treatment approaches that allow for substance use disorders and other mental health disorders to be addressed simultaneously will undoubtedly decrease barriers to treatment access for the large proportion of patients seeking recovery from multiple conditions. Therefore, it is imperative that clinician trainees and all patient-facing staff in mental health facilities receive proper education and training in issues related to substance use disorders. Such training may involve early identification of problematic substance use and management of acute signs of overdose. Additionally, as demonstrated in this study, it remains unknown which integrated treatments are optimally effective in treating substance use disorders in the context of PTSD and other co-occurring mental health conditions. Therefore, the field would benefit from continued funding to support research on novel treatment development and evaluation.

CITATIONS

Norman, S. B., Trim, R., Haller, M., Davis, B. C., Myers, U. S., . . . Mayes, T. (2019). Efficacy of integrated exposure therapy vs integrated coping skills therapy for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0638