Alcohol Use Disorder Patient Characteristics Associated with Primary Care Versus Specialty Care Receipt

Identifying characteristics associated with treatment receipt for alcohol use disorder can help reframe strategies designed to improve treatment rates and possibly early detection.

Given that treatment can occur in primary healthcare and specialty care, should we assume that co-occurring patient characteristics are the same across both settings?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Alcohol use disorder is among the most prevalent mental disorders in United States and across the globe. In the European Union, for example, there were 23 million people who met criteria for an alcohol use disorder in 2010. Overall, alcohol use disorder has the second highest burden of disease of all mental disorders (i.e., health, social, and financial cost). Despite the high prevalence of alcohol use disorder, treatment rates have been the lowest of all major mental disorders averaging about 10% in Europe during the past decade.

The researchers suggested that the low treatment rate could be explained viewing alcohol use disorder on a severity continuum, where only those with very severe alcohol use disorder are in need of formal treatment, while those with less severe forms might recover without formal services. The researchers in this study sought to understand how different treatment pathways (primary care versus specialty care) are associated with different characteristics of severity – with the prediction that patients with more severe profiles would be more likely to seek treatment, and those with the most severe profiles would do so in specialty care settings.

They were especially interested in:

- the roles of drinking behavior

- social disintegration (i.e., degree of unemployment, not being married, low-socioeconomic status)

- comorbidities of the somatic nature (hypertension and liver)

- mental comorbidities

- impaired functioning due to drinking

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors used cross-sectional data (e.g., data collected at one time point) from 8,476 patients from primary health care across six European countries and 1,762 patients from specialized health care (e.g. inpatient or outpatient clinics) across eight European countries (age range = 18 – 64).

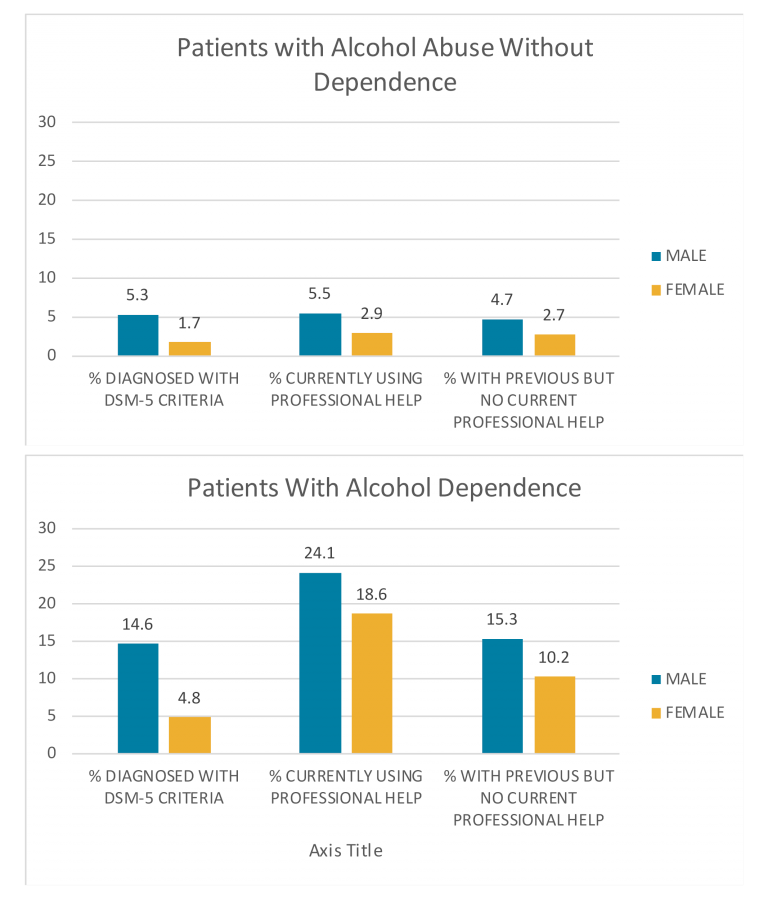

First, the authors sought to describe the 12-month prevalence of alcohol use disorder and treatment found in primary care settings according to gender.

Next, for descriptive purposes, six groups of patients were identified based off DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria, treatment receipt, and setting (primary care versus specialty care). Specifically, group memberships were created under the hypotheses that severity of associated characteristics will progress from least to most in the following order:

- no alcohol use disorder (primary care)

- alcohol use without treatment (primary care)

- alcohol dependence without treatment (primary care)

- alcohol use disorder with treatment (primary care)

- < 4 DSM-5 criteria (of a possible 11, consistent with a mild alcohol use disorder; specialty care)

- ≥ 4 DSM-5 criteria (consistent with a moderate or severe alcohol use disorder; specialty care)

In order to gain a better understanding of how the six groups differed in terms of the severity of associated characteristics, they examined linear relationships with drinking behaviors, social disintegration, somatic and mental health comorbidities, and loss of functioning after controlling for the participants age and country of residence.

The final analysis tested if the receipt of treatment for alcohol use disorder, in primary care and in and a specialty treatment setting, could be predicted by groups of severity characteristics.

A few terms deserve clarification:

- Specialty treatment refers to mostly inpatient or outpatient treatment that specifically targeted alcohol use disorder.

- Primary care refers to general health care. In primary care (unlike specialty care), all general practitioners assessed their patients independently in addition to a participant interview which was conducted over the phone for both treatment settings.

- Treatment was defined broadly in this study, including interventions delivered by a range of health care professionals.

- Drinking behavior was measured by amount of alcohol used daily, chronic heavy drinking daily (100+ g ethanol daily; roughly a minimum of 7 US standard drinks/day), binge drinking weekly (200+ g per week), and numbers of heavy drinking days in the past 30 days

- Social disintegration refers to the degree of unemployment, not being married, low-socioeconomic status, etc.

- Somatic comorbidities were examined with hypertension and liver problems.

- Mental health comorbidities were measured as anxiety, depression, or severe psychological distress.

- Loss of functionality was measured with number of days of being unable to carry out usual activities within past 30 days and the number hospitalized nights in the past 60 days.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Examination of the overall primary care sample of 8,476 patients showed that 12-month prevalence of alcohol use disorder was 11.8%, and higher among men (19.9%) than women (6.5%). Of the primary care patients diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder, the percentage currently in treatment was low (17.6%) but more men were in treatment (19.1%) than women (14.5%).

Patients in the no alcohol use disorder (primary care) group had the lowest levels of behavioral drinking, social disintegration, and mental comorbidity compared to patients in the ≥ 4 DSM-5 criteria (specialty care) group which had the highest.

In order to gain a better understanding of how the six groups differed in terms of the severity of associated characteristics linear relationships were examined between group membership and severity characteristics. The magnitude of behavioral drinking, social disintegration, mental comorbidity, and number of nights spent in a hospital within the past 6 months (an indicator of functionality loss) had a linear increase across group membership.

Unlike the characteristics displayed in the figure above, somatic comorbidities (hypertension and liver) and number of days of being unable to carry out usual activities with past 30 days (another indicator of functionality loss) also showed a mostly linear increase across the order of primary care groups, however, the linear increase was not as consistent into the specialty care groups. Additionally, the relationship between hypertension and group membership was present for men but not for women.

Overall, the six groups almost looked like separate samples, which could be divided based on the covariates presented. Specifically, treatment status (any versus no treatment) was correctly predictive of 95.5% of the cases, with a sensitivity of 70.0% (i.e., proportion of treatment seekers correctly identified) and a specificity of 98.4% (i.e., proportion of non-treatment seekers correctly identified). The covariates could similarly predict specialty care treatment versus all other groups in 95.3% of the cases, with a sensitivity of 76.5%, a specificity of 98.2%. The strongest predictors in both models were average daily alcohol intake, anxiety, severe psychological distress, number of hospitalized nights, and sex.

The final analysis showed that the best predictive power could be found for average alcohol consumption & anxiety, both in the expected direction of greater severity (more drinking and anxiety) predictive of treatment seeking.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Alcohol use disorders were quite prevalent in primary care settings; in fact, the prevalence was twice as high compared to general population surveys of Europe. It is likely that individuals with alcohol use disorder experience more health complications than the general population and are therefore more likely to seek attention in primary care settings.

The data seem to indicate that most treatment at the primary care and specialty care level in Europe is delivered to people with a high level of existing comorbidity, however, the severity of comorbidities may systematically increase according to alcohol use disorder severity and setting. This implies a stepped care approach (treatment given at the lowest appropriate service tier and ‘stepping up’ to more intensive services as required) based on drinking level and associated harm could be further investigated.

The take-home message: receiving treatment was highly predicted by variables from the following categories:

- average daily alcohol intake

- anxiety

- severe psychological distress

- number of hospitalized nights

- sex.

In other words, people with very severe alcohol use disorder were referred to treatment in general, and to specialty treatment in particular, based on these groups of predictors.

The final analysis showed that the best predictive power of treatment could be found for average alcohol consumption and anxiety.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The most important limitation of this study – like other cross-sectional studies – is there is no way of knowing if the characteristics associated with alcohol use disorder and treatment (e.g., social disintegration, somatic and mental health comorbidities) came before the onset of alcohol use disorder or after. In other words, temporal precedence could not be established, so the associations between these severity characteristics and alcohol use disorder may offer limited utility in early screening and detection until the timing of onset is established in a longitudinal or perhaps, retrospective framework.

NEXT STEPS

Given the low levels of treatment in the primary care setting relative to the number of patients with alcohol use disorder, future research should determine if the decision making process by which a general practitioner decides to screen for alcohol use disorder or refer to treatment is the best possible for the treatment system and patient care.

Additionally research is needed to determine if less intensive, but still targeted treatment approaches would be good for this population. Through this approach, patients are still receiving treatment without the intensity of specialty care that can be overwhelming for some.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: This study showed that individuals utilize different “treatment pathways” through both primary care and specialty care for alcohol use disorder. This study cannot speak to whether primary care treatment was more or less effective than specialty treatment for remission from alcohol use disorder. However, this study did show that patients with the more severe characteristics (e.g., average daily alcohol intake, anxiety, severe psychological distress, number of hospitalized nights, and sex) are often receiving treatment at specialty care settings. Given the large array of disabling diseases and disorders caused by alcohol use disorder, it is recommended to talk to your primary care practitioner or a specialty treatment provider if you are struggling with alcohol use.

- For Scientists: This cross-sectional study of more than 10,000 patients highlighted associations between the severity of individual characteristics that co-occur with alcohol use disorder in primary and specialty care settings. Given that different covariates predicted treatment receipt, future research should investigate the accuracy of these characteristics in early screening and identification.

- For Policy makers: This study assessed prevalence rates of alcohol use disorder found in primary care settings across six countries in the European Union. The prevalence rate of alcohol use disorder found in primary care settings was more than twice as high as found in the general population. This highlights the degree to which individuals with these disorders actually interface with general practitioners and thus underscores the opportunity for primary care doctors to screen routinely for these debilitating disorders. Prioritizing research funding that investigates the potential role that general practitioners can play in identifying and treating early signs of alcohol use disorder could yield high dividends.

- For Treatment professionals and treatment systems: Many interventions for early stage alcohol use disorder, as well as early stage anxiety, depression or hypertension can be initiated in primary care. If not comfortable treating the condition in primary care, however, it is recommended that treatment providers refer patients to specialty care providers.

CITATIONS

Rehm, J., Manthey, J., Struzzo, P., Gual, A., Wojnar, M. (2015). Who receives treatment for alcohol use disorders in the European Union? A cross-sectional representative study in primary and specialized health care. European Psychiatry, 30, 885-893. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.07.012