Brain Imaging to Understand Adolescent Cannabis Recovery

Cannabis use among adolescents has been on the rise. 10% of all users, will go on to develop a cannabis use disorder. This study examines how brain imaging may help the field better understand how adolescents recover from cannabis use disorder, and ultimately provide innovative ways to identify heightened risk for relapse.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Three out of 100 adolescents 12-17, and five out of 100 young adults 18-25 have a cannabis use disorder – meaning they continue to use marijuana or other forms of cannabis even though it impairs their functioning or has a negative impact on their mental and physical health. There is still much to be learned about how cannabis use affects the brains of adolescents, and then, even more to learn about how the brain changes after those with cannabis problems initiate abstinence.

One key brain structure in understanding cannabis and other substance use disorders is the anterior cingulate cortex – it is implicated in emotional regulation, an important process in addiction recovery (e.g., coping with intense, unpleasant feelings). In this study, authors tested whether the connectivity (strength of communication pathways) between the anterior cingulate cortex and other areas of the brain associated with reward and regulation helped predict cannabis use over time in adolescents who completed addiction treatment.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Two groups of adolescents and young adults (10-23 years) from two nearby, metropolitan areas in a Midwestern state were followed over 18 months, completing brain scans (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging – which measures activity in specific areas of the brain) when they entered the study (i.e., baseline) and at the 18-month follow-up. They also answered several questions about their substance use and other areas of their mental health, and completed drug toxicology screens, at baseline, 9-month follow-up, and 18-month follow-up.

The first group consisted of 22 adolescents with cannabis use disorder based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) who had just completed addiction treatment (7 days ago, on average) and were abstinent from all drugs. They were 17 years old, on average, and 64% were male. The second group consisted of 43 “healthy” controls who had no history of a substance use or other psychiatric disorder. They were 16 years old, on average, and 53% were male. Study authors made efforts to equalize the groups on age, sex, and handedness (left vs. right); they also had similar socioeconomic status, on average. Given the range of emotional and cognitive difficulties associated with the presence of a cannabis use disorder among adolescents, it is not surprising that this group had lower full scale IQs when beginning the study (IQ = 99 – about the 50th percentile) – albeit average relative to the general population – compared to the controls who had an IQ in the high average range (IQ = 116 – about the 85th percentile).

Authors were interested in answers to the following three main research questions:

- Do the cannabis use disorder and control groups have different connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and other reward and regulation focused areas of the brain, and does that connectivity mature at different rates?

- Is there a relationship between this connectivity when adolescents enter the study and cannabis use over time?

- Is there a relationship between cannabis use over time and this connectivity at the end of the study?

They were also interested in whether cannabis use across the 18-month study window helped predict IQ and ability to give sustained attention at the 18-month follow-up, above and beyond their IQ and attention at baseline.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

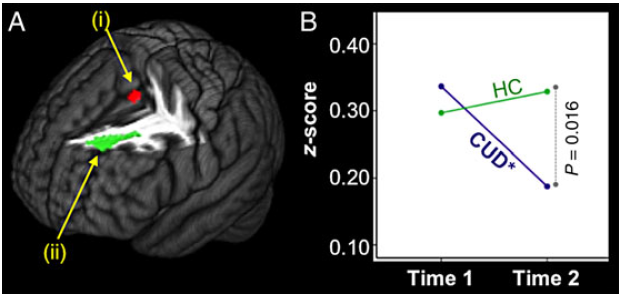

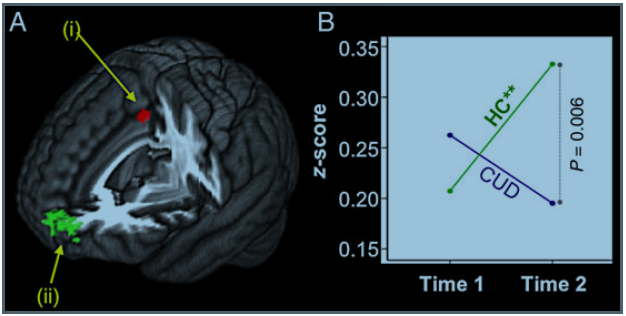

The connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (an area of the brain that contributes strongly to decision making), and the connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and the superior frontal gyrus (an area of the brain related to people’s ability to store and manipulate information in short-term memory (working memory)), decreased over time in the cannabis use disorder group, and did not change over time in the control group.

This pattern can be seen in the figures below which show brain images –

- the red light represents the anterior cingulate cortex

- the green light represents the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in the first picture, and the superior front gyrus in the second picture

- the “HC” line represents the control group

- the CUD line represents adolescents with cannabis use disorder

In exploratory analyses, only the cannabis use disorder group members who relapsed (defined as any cannabis use) showed the decline – suggesting that either:

- a) the cannabis use itself is accounting for the decreased connectivity

- b) that the decreased connectivity is accounting for the cannabis use

- c) that psychological and cognitive challenges may drive a process that both makes it more difficult for them to stay abstinent while also stunting the maturation of the connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and these other brain areas.

Another key finding in the study is that at baseline, less connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex (a brain structure responsible in part for decisions related to reward, and reward-based learning (i.e., learning related to substance use and the pleasurable feelings that it produces)), predicted more cannabis use across the 18-month study period. This relationship was present even when adjusting for how much cannabis and alcohol the adolescent used when the study began, as well as their age.

In addition, after adjusting for baseline IQ, for all of the adolescents in the study, each day of cannabis use during the 18-month study period was related to a reduction in .19 IQ points at the 18-month assessment, a significant relationship. When alcohol was also considered, however, the relationship was no longer significant – and alcohol alone was not a predictor of lower IQ – suggesting it may be the combination of cannabis and alcohol that helps explain lower IQ performance at the end of the study. Cannabis use predicted slower reaction time at the final assessment as well, even when considering alcohol use over the same time period (alcohol use did not predict slower reaction time on its own). This finding suggests, in contrast with IQ performance, that cannabis on its own might help explain slower reaction time at the final assessment.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

The results from this study comparing the brain images of adolescents over time who recently sought treatment for cannabis use disorder, and “healthy” adolescents with no history of substance use or other psychiatric disorder, point to the connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex as a potential biological marker (i.e., “biomarker”) of relapse risk. Given the novelty of this finding, and how few studies follow adolescents over time with multiple brain image assessments, more research is needed to replicate and further understand its implications in terms of real-world behavior beyond cannabis use. For example, what is it about this lower connectivity that leads to an increased relapse risk? This lower functional connectivity could be a marker for lower cognitive control, especially as related to thinking through behavior and its subsequent rewards and consequences.

Delayed discounting is a process discussed in prior Recovery Research Institute Bulletin articles, showing that individuals who do worse in substance use disorder treatment tend to overvalue short-term smaller rewards over longer-term larger rewards – leading them to choose drug taking over abstinence (abstinence facilitates broader, more lasting rewards down the road (e.g., better grades at school, improved relationships, and improved physical health)). Indeed, a certain level of cognitive control is needed to maximally benefit from many empirically-supported psychosocial treatments that address substance use disorder, such as cognitive-behavioral and motivational enhancement therapy. In other words, added cognitive training to bolster cognitive control – such as working memory training – may be needed for these at-risk adolescents with reduced connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and orbitofrontal cortex.

In addition, cannabis use could hinder typical brain maturation in adolescence, specifically related to reward-based learning. These results are in line with a study of young adults, where Gilman and colleagues showed even recreational marijuana use – relative to little or no marijuana use – is related to structural differences in an area of the brain responsible in part for processing of emotional rewards, the nucleus accumbens.

Finally, while it is possible that cannabis use, on its own, is related to decreased IQ performance over time, more likely is that the combination of cannabis use and other behaviors likely to accompany it in adolescents, such as alcohol use, is accounting for impaired performance on problem solving and verbal processing tasks.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Brain image assessments were administered after completing treatment. Whether connectivity between areas of the brain implicated in self-regulation and reward based learning can identify individuals at greater relapse risk at the beginning of treatment – for all patients including those who may drop out – cannot be determined from this study.

- While number of days of cannabis use is an important measure of treatment outcome, clinical wisdom suggests how many times per day, and the potency of the cannabis being smoked (or consumed) are also likely to be important outcomes. Only days of cannabis use was measured in this study.

- While the cannabis use disorder and control group were similar on key demographic characteristics, the sample was small. This means that significant differences were difficult to detect because statistical significance depends in part on having a large enough sample size. Developmentally, a one year difference (17 and 16 years old) may not have been statistically significant, but could have nevertheless been an important difference in understanding the study results.

NEXT STEPS

Addiction-related brain processes that underlie the thinking and feeling connected to worse (or better) outcomes, add another layer of evidence to help understand addiction treatment and recovery. Next steps in this research might include adding measures of impulsivity, including but not limited to delayed discounting, to understand better the potentially critical finding in this study showing reduced connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and orbitofrontal cortex could be a biomarker for elevated relapse risk.

Moreover, there is a lack of research investigating whether brain imaging allows us to better predict who is actually at greater risk for relapse. It may be worth pursuing a less costly, more convenient assessment (e.g., a delayed discounting assessment) to identify these factors that increase risk for relapse.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Research studies like this one that get multiple images of the brain over time can help shed light on how the brain changes in the context of substance use disorder treatment and recovery. This way we can know what kinds of tasks people will recover functioning on, and where they might continue to have trouble with performance. Brain images also provide opportunities to identify brain differences that are “biomarkers” (i.e., observable signs based on a test of physical or other medical functioning) for worse treatment outcomes. Identifying these at-risk individuals can provide opportunities to modify their treatment based on their unique needs, often called “personalized medicine.” This study provides preliminary evidence that, for adolescents with cannabis use disorder, the connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex, a structure involved in emotional learning, and the orbitofrontal cortex, a brain structure responsible in part for decisions related to reward and reward-based learning (i.e., learning related to substance use and the pleasurable feelings that it produces), could be one of these potential biomarkers. Much more research is needed to examine this possibility, and what should be done to help intervene if it indeed it is a helpful biomarker of relapse risk.

- For scientists: This longitudinal study provides preliminary evidence that for adolescents with cannabis use disorder, the connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex, a structure involved in emotional learning, and the orbitofrontal cortex, a brain structure responsible in part for decisions related to reward, and reward-based learning (i.e., learning related to substance use and the pleasurable feelings that it produces), could be a potential biomarker of relapse risk. Much more research is needed to examine this possibility. Furthermore, research is needed to determine if neuro-imaging provides statistically and clinically significant incremental validity over other forms of assessment that might be less costly and easier to administer.

- For policy makers: Research studies like this that measure an individual’s brain functioning at multiple points in time, can help shed light on how the brain changes in the context of substance use disorder treatment and recovery. This way we can know what kinds of tasks people will recover functioning on, and where they might continue to have trouble with performance. Brain images provide opportunities to identify brain differences that are “biomarkers” (i.e., observable signs based on a test of physical or other medical functioning) for worse treatment outcomes. For adolescents with cannabis use disorder, the connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex could be a potential biomarker. Allocating funding to examine this possibility might help provide answers on the utility of brain image assessments, and, subsequently, what should be done to help intervene if and when biomarkers of relapse risk are discovered.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This longitudinal study provides preliminary evidence that for adolescents with cannabis use disorder, the connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex could be a potential biomarker of relapse risk. Much more research is needed to examine this possibility, however, and what should be done to help intervene if it indeed is a helpful biomarker of relapse risk. Furthermore, research is needed to determine if neuro-imaging provides clinically significant incremental validity over other forms of assessment that might be less costly and easier to administer. At this point, using neuroimaging findings to aid in treatment may not be feasible, though their results can be used to understand better treatment and recovery processes over time.

CITATIONS

Camchong, J., Lim, K. O., & Kumra, S. (2017). Adverse effects of cannabis on adolescent brain development: A longitudinal study. Cerebral Cortex, 27(3), 1922-1930.