Brain Stimulation as Addiction Treatment: Science Fiction, or an Effective Option?

Addiction is a leading cause of disability around the world and we are continuing to find ways to enhance treatment and recovery outcomes. Could brain stimulation techniques be the latest addition to our line-up of effective treatments?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Addiction is a disease that affects the brain. As addiction progresses, drugs change the brain’s structure and the way it functions, and these observable changes lead to maladaptive behaviors like compulsive drug seeking and use despite negative consequences. Treatments for substance use disorder aim to heal the brain and change harmful behaviors. While many empirically-supported pharmacological and behavioral interventions are available for treating addiction, relapse is common and our pursuit to enhance current treatments and discover new ones continues. This review evaluates recent research assessing the therapeutic potential of brain stimulation techniques for treating substance use disorders.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors performed an extensive review on 60 studies, conducted between the years 2000 and 2017, that assessed the effects of brain stimulation on substance use disorder outcomes. The authors entered specific search terms into databases containing hundreds of thousands of scientific articles to find the studies that met their specific criteria to be included in this review. Studies meeting their criteria needed to assess one of three brain stimulation techniques.

THESE TECHNIQUES INCLUDE:

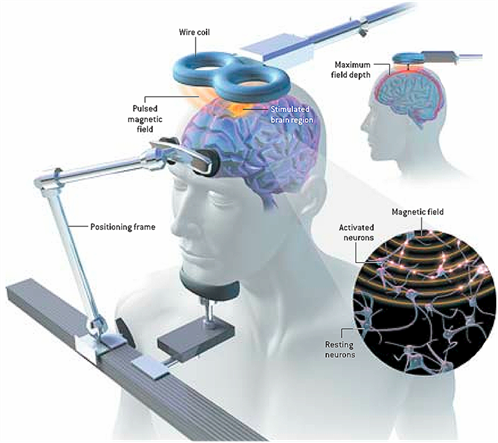

- rTMS: Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

-

Activating or suppressing activity in a specific brain site by holding a magnet (AKA electromagnetic coil) against the head near that site and sending short pulses of electrical current through the magnet, which painlessly pass through the forehead and stimulate brain cells in the desired area.

SOURCE: Bryan Christie Design

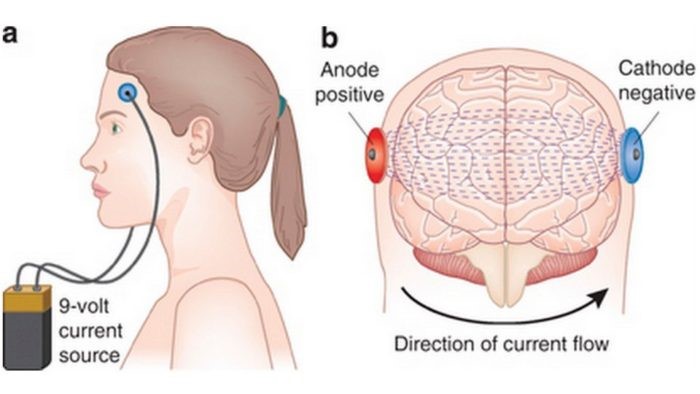

- tDCS: Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation

-

Activating or suppressing the activity of specific brain regions by sending a constant low-intensity current through two or more electrodes placed on the head. This painless and noninvasive technique is very similar to rTMS.

SOURCE: Valentin, L. S. S., Fregni, F., & Carmona, M. J. C. (2015). Effects of the Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Prevention of Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction after Cardiac Surgery: Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. J Neurol Stroke, 3(1), 00078.

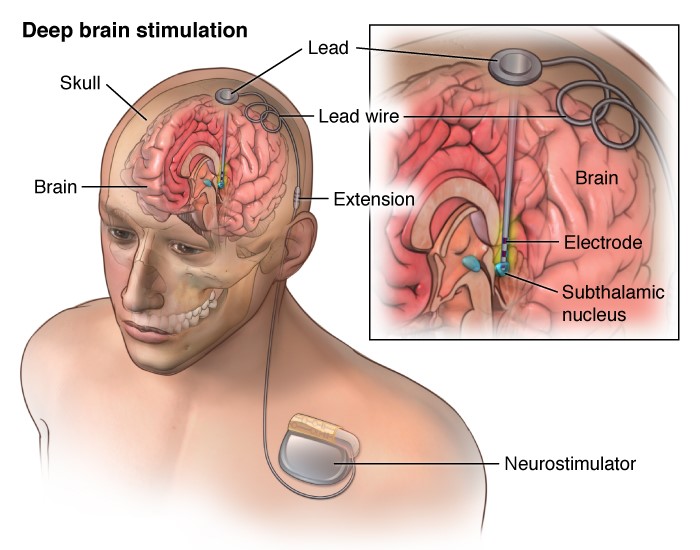

- DBS: Deep Brain Stimulation

-

Unlike rTMS and tDCS, which are noninvasive, this technique requires brain surgery. Two small electrodes are placed on either side of a specific brain structure. These electrodes are attached via thin wires to battery-operated generators placed in the chest. Electrical pulses continuously pass from the generators to the electrodes in the brain, which stimulate brain cells in that specific area. This technique can continuously target specific structures deep within the brain and directly manipulate brain circuits associated with drug-related rewards.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

The studies included in this review also needed to measure the effects of these brain stimulation techniques on specific outcomes including, substance use (e.g., reducing or stopping use after treatment) and craving (in general and/or during exposure to drug cues, for example, craving in response to viewing images of a beer bottle). All studies evaluated people diagnosed with a substance use disorder (drug or alcohol abuse / dependence based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, or DSM).

In general, investigation typically consisted of an active group, which received the brain stimulation treatment, and a sham group. The sham group believed they were receiving the treatment, but either no actual brain stimulation occurred, or stimulation was applied to a brain region that is thought to be unrelated to addiction processes (e.g., motor cortex). A sham condition helps researchers determine the effectiveness of the actual treatment, accounting for the possible effects of general study participation, including the belief that they will get better from the treatment, usually called a “placebo effect”.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

rTMS (28 studies):

Investigations of rTMS show promising results for alcohol dependence, nicotine dependence, cocaine dependence, and methamphetamine dependence. In these studies rTMS generally had a large effect on craving and/or substance use, with rTMS patients showing reduced craving and consumption relative to sham treated patients or their own pre-treatment measures (craving and use before rTMS). However, these positive treatment effects were largely specific to studies that administered multiple rTMS treatments. Studies implementing a single treatment had less successful outcomes. Stimulating frontal brain regions, particularly the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (plays an important role in reward processing, motivation, and behavioral control), also seems to produce the best outcomes. Only one study assessed rTMS for cannabis use disorder, which showed no effect of rTMS on craving. None of the rTMS studies included in this review addressed opioid use disorder.

tDCS (23 studies):

Fewer tDCS studies have been conducted. Among them, tDCS is shown to reduce alcohol, nicotine, and cocaine craving and/or consumption compared to sham treatment and pre-treatment measures. Similar to rTMS, positive tDCS treatment effects are generally observed when the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is stimulated and when individuals receive multiple treatment episodes, but the size of this effect on craving and consumption is less consistent across tDCS studies, ranging from small to large. Treatment sessions lasting longer than 10 minutes also seemed to be more effective. The effects of tDCS in individuals with methamphetamine, opioid, and cannabis use disorders have each been evaluated in only one study. Although each of these studies show promise for tDCS as a potential treatment across these three substance use disorders, it is too early to make conclusions about its therapeutic effects.

DBS (9 studies):

Interestingly, all DBS studies revealed positive results, with DBS in the nucleus accumbens (a structure deep in the center of the brain, also associated with processing drug-related rewards) decreasing craving and/or consumption of alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, and opioids. However, given that surgery is required for this procedure, available data are limited to small sample sizes that range from one to ten participants and many studies are based on a single participant (i.e. case studies).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This review highlights the potential for brain stimulation techniques to help treat a variety of substance use disorders. More research is needed to fine-tune these techniques, better understand their mechanisms of action, and make formal conclusions about their effectiveness. Still, they pose an intriguing potential treatment option for those who have not had much success with standard treatments and seek alternative therapies. Given the noninvasive nature and relatively low cost of rTMS and tDCS, exploring their potential therapeutic benefits for treating substance use disorders is certainly worthwhile. Despite the invasive procedures needed for administering DBS, it could ultimately prove to be a potential option for those suffering from more severe substance use disorders who have tried all other treatment options to no avail.

Although these brain stimulation techniques seem to produce positive outcomes in the short-term, this review also underscores the need for further investigation before they can be implemented clinically. Importantly, the long-term effects of brain stimulation are not yet clear. Exceptionally few studies have followed patients over time to see how long these treatment benefits last. To date, sham-controlled studies have found both positive and negative long-term outcomes (e.g., 6 months, 1 year) after brain stimulation treatments, with higher relapse rates and improved abstinence rates observed in actively treated patients compared to sham treated patients. However, the effects of brain stimulation beyond the first few weeks or months are vastly understudied. Prospective research can help us identify what these long-term effects are, and whether or not it has important implications for addiction treatment.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Most of the studies included in this review assessed small sample sizes and findings within studies are sometimes mixed depending on the outcome measure assessed (e.g., reduced craving but increased relapse rates in the same treatment sample). Therefore, these findings are largely preliminary. More research is undoubtedly needed to clarify discrepancies and determine if the effects of each brain stimulation technique vary by population or treatment characteristics. As this line of research progresses, we can more clearly identify the optimal length of treatment, the intensity at which stimulation is needed to see therapeutic benefits, and the specific substance use disorder populations for whom these benefits are seen.

- This review focused on craving and substance use as outcome measures. Examining the effect of brain stimulation on other outcome measures, such as emotional stability and life satisfaction, will be important for assessing the overall effectiveness of these techniques as potential treatments for substance use disorders.

- The articles reviewed here consist of small sample sizes that typically included 40 or fewer participants. To gauge the true impact of these techniques, larger randomized controlled trials are needed.

- Given the few studies conducted to-date, this review did not exclude research assessing individuals with with co-occuring mental or physical health problems. Co-occuring conditions, such as HIV, bipolar disorder, or major depression have the potential to influence treatment outcomes and investigation is needed to determine their role.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Research continues to find new and promising treatments for addiction. Short-term treatment with brain stimulation might ultimately prove to be an effective treatment option for substance use disorders. By stimulating brain areas implicated in addiction and reward, we may be able to help individuals stop harmful addiction-related behaviors. Research so far suggests that these brain stimulation techniques might help reduce craving and substance use, but more research is needed to identify who is most likely to benefit from brain stimulation, determine its long term effects (i.e. effects beyond the first few weeks/months after receiving the treatment), and make formal conclusions about its overall effectiveness.

- For scientists: Brain stimulation techniques have become a hot topic in the addictions research community. This review suggests preliminary evidence of their effectiveness in reducing substance use and craving among individuals with various substance use disorders. Still, small sample sizes, a limited literature, and scarce evaluation of their long-term effects demands further investigation. It is important to identify the optimal therapeutic dose (i.e. strength and duration of brain stimulation) and whether beneficial effects can be maintained after treatment. Examining the neurobiological mechanisms of action that underlie the effects of brain stimulation, and investigating the factors that moderate outcomes can ultimately facilitate this line of work. Although this area of study is in its infancy, brain stimulation research has yielded significant promise to-date and further investigation could give way to a viable treatment option for individuals suffering from pervasive substance use disorders.

- For policy makers: Addiction is a disease that changes the brain’s structure and function, and and these changes lead to harmful behaviors like compulsive drug seeking and use despite negative consequences. Substance use disorder treatments aim to heal the brain and change behavior to promote recovery, and research is continuing to reveal new and effective treatments for tackling this significant public health problem. Brain stimulation techniques may facilitate recovery by reducing substance use and craving. This review highlights their potential but underscores substantial need for additional research to identify the appropriate strength and duration of treatment, for whom the treatment is most effective, as well as its long-term effects. Additional funding is needed to explore the full extent of brain stimulation’s benefits before it can be safely and effectively implemented in clinical settings. Investigating therapies like these could ultimately lead to novel, effective and relatively inexpensive options for those who have not benefited from standard therapies and require alternative approaches to addiction treatment.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Existing research suggests that stimulating brain regions affected by addiction and involved in the brain’s reward circuitry, may halt maladaptive behaviors and promote healthy ones. Although these brain stimulation techniques seem to produce generally positive outcomes, this review also highlights the need for further investigation before they can be implemented clinically.

CITATIONS

Coles, A. S., Kozak, K., & George, T. P. (2018). A review of brain stimulation methods to treat substance use disorders. The American journal on addictions, 27(2), 71-91.