Brief Interventions at the Pharmacy?

Dozens of randomized controlled trials suggest that brief interventions (30 minutes or less) delivered in primary health care settings can reduce drinking by 1 to 3 drinks per week, on average, and may also reduce the incidence of risky or problematic drinking.

The pharmacy is another potential point of access to the health care system; pharmacists are the third largest group of health care workers in the world, behind doctors and nurses.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Dhital and colleagues tested whether individuals who received a brief intervention delivered by a pharmacist had better drinking outcomes 3 months later compared to those who received an educational brochure on alcohol related harms.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Dhital et al. used a randomized controlled trial to compare a pharmacist-delivered 10-minute alcohol intervention to an educational brochure among 407 adults in London, United Kingdom (205 vs. 202, respectively) who scored between 8 and 19 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Thus, the study focused on “at-risk” drinkers and excluded individuals with low levels of drinking (< 8) and those reporting more severe drinking (20 or greater), possibly reflective of a moderate-severe alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Pharmacists (N = 17, working at 16 pharmacies) received 3.5 hours of training in how to deliver the intervention, which was based on motivational interviewing (MI). Specifically, patients who were interested in learning more about the study or about alcohol in general, as well as those who purchased an over-the-counter product, received a pharmacy service, or had a prescription for a condition that might be related to, or affected by, alcohol use (e.g., cardiovascular disease, depression, smoking cessation, and sleep difficulties) were asked to participate and initially screened for eligibility.

Those who met eligibility criteria and agreed to participate were assigned to either the intervention or comparison group based on pre-determined random assignment – pharmacists were unaware to which group each person was assigned until they opened a sealed envelope to reveal group assignment. For those in the intervention group, the pharmacist brought the participant into a private room behind the pharmacy counter and asked participants to “talk about how drinking fitted in with their lives, explore any ambivalence and [evaluate] their drinking.” For those in the comparison group, the pharmacists only provided an educational leaflet on alcohol.

Study participants were about 40 years old, on average; 54% were male and approximately 75% were White.

Primary outcomes measured 3 months after receiving the intervention or comparison brochure were:

- improvements in the AUDIT score

- the proportion that no longer met the AUDIT cut-off score of 8 signifying they no longer were drinking at risky levels

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

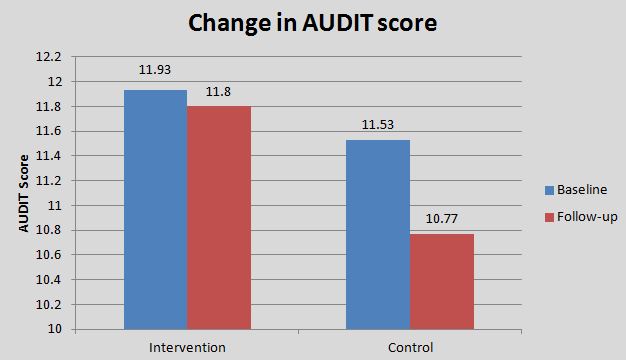

Controlling for any differences in AUDIT scores when they entered the study and for the pharmacist who delivered the intervention (in case certain pharmacists were more effective than others), there were no differences in AUDIT scores at 3-month follow-up.

Lack of differences persisted even after the authors ran a series of rigorous analyses to see if differences in drop-out or demographics between groups might bias the results in favor of the intervention or the comparison condition.

Also, the proportion who no longer reached the AUDIT risky drinking cut-off of 8 was similar across groups at 3-month follow-up (23% intervention vs. 27% control). In their examination of secondary outcomes (AUDIT subscales and general health), outcomes were either similar or actually favored the control group.

Although brief alcohol interventions can feasibly be implemented in pharmacies, as delivered in the current study (10 minute intervention where pharmacists received 3.5 hours of prior training), they may be unlikely to help more than just handing out a brochure.

There is the possibility that simply being asked about their alcohol use – as was the case in the control group – could lead to reductions in drinking and would make it harder for the intervention to produce an effect over and above that effect of simply being assessed, although that explanation does not seem to account for the interventions lack of advantage.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Identifying another setting where the general public are likely to go to deliver brief alcohol interventions might enhance public health by reducing alcohol consumption and alcohol related harms.

The current study raises the possibility that the degree to which individuals perceive the person giving the health advice as an expert may impact how much they benefit from the intervention.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The pharmacy context itself may also not be the most ideal place to provide a brief alcohol intervention.

- The study was conducted in a rigorous manner. All staff who could be blinded (e.g., those collecting data) were unaware of whether participants received the intervention or comparison brochure, and a series of statistical analyses were conducted to rule out other factors that might have accounted for any potential differences between the study conditions. Although not a limitation of the study design, per se, the limited training of the pharmacists (3.5 hours) may have factored into finding a non-significant effect of the intervention. As the authors noted in their study, in a separate trial of brief alcohol intervention in primary care where training of staff was limited by naturalistic circumstances, the comparison brochure did as well as the brief intervention just like the current study (see here). Thus, more intensive training in the delivery of brief interventions may be needed to really make a difference.

- Another possibility is that pharmacists may not have the same degree of perceived “medical” credibility and influence as a physician. Brief intervention (30 minutes or less) delivered by a medical doctor may be more potent in changing patients’ drinking behaviors.

NEXT STEPS

Next steps are to test whether pharmacists with more training in the assessment of alcohol problems and delivery of brief alcohol interventions may be more effective in reducing individuals’ alcohol use than they were in the current trial.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: The current study was geared toward individuals with risky levels of drinking that were less likely to have alcohol use disorder. While the study is important from a public health perspective, it may have little direct application to specific individuals seeking recovery.

- For scientists: The current study was the most rigorous examination of brief alcohol interventions in pharmacy settings to date. While the study was internally valid, it may prove fruitful to change elements of the treatment (e.g., increase pharmacist training) and re-evaluate the intervention. Conducting some systematic qualitative investigation on the recipients of the intervention itself might also inform how the intervention might be conducted differently and hopefully to greater effect.

- For policy makers: An intervention by a pharmacist could be helpful as pharmacists are a common point of contact for many people. Brief alcohol intervention as delivered in the current study, however, is unlikely to provide public health benefit. Changes to the intervention may be needed; consider allocating funding for such changes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The current study was geared toward individuals with risky levels of drinking that were less likely to have alcohol use disorder. While the study is important from a public health perspective, it has little application to addiction specialists. For individuals in a position to deliver brief alcohol interventions (e.g., primary care doctors and nurses), this study, along with a study by Kaner et al. mentioned above in “What are the limitations of this study?” suggest more in-depth training and monitoring of brief interventions may be needed to help patients reduce their drinking compared to offering them an educational brochure.

CITATIONS

Dhital, R., Norman, I., Whittlesea, C., Murrells, T., & McCambridge, J. (2015). The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions delivered by community pharmacists: randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 110(10), 1586-1594. doi:10.1111/add.12994