No one left behind: Buprenorphine (Suboxone) for adolescents and young adults with opioid use disorder

In the United States, approximately one million young adults (age 18-25) and half a million adolescents (age 12-17) report regular non-medical use of opioids; however, few studies have evaluated buprenorphine (i.e., Suboxone) treatment for youth with opioid use disorder. This study tested whether youth with opioid use disorder who received a longer buprenorphine taper did better than those who received a shorter one. Results showed that the longer (56-day) taper produced better opioid abstinence and retention outcomes than shorter (28-day) taper for youth with opioid use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Since the 1990’s, the United States has experienced a rapid spike in opioid use disorder and opioid-related overdoses, with more than 130 overdose-related deaths happening every day. Importantly, approximately one million young adults (age 18-25) and half a million adolescent (age 12-17) report regular non-medical use of opioids, making this a particularly high-risk group for opioid-related harms. Medications for opioid use disorder help reduce opioid use and risk for overdose, while improving the likelihood that people stay in treatment (i.e., treatment retention). Opioid agonist medications, like buprenorphine (commonly referred to by the brand name Suboxone), provide stable low–level stimulation of opioid receptors and block the effects of other opioids (e.g., heroin). While buprenorphine is well established as an effective medication for adults with opioid use disorder, its safety and efficacy for youth remains unclear, given little research has been conducted on buprenorphine treatment for youth with opioid use disorder. As a result, the optimal length of administration for youth remains undetermined. To address this gap, Marsch and colleagues evaluated the relative efficacy of a 28-day and a 56-day long buprenorphine taper in promoting abstinence from opioids and treatment retention among this high-risk yet understudied group.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a double-blind, placebo controlled, multicenter randomized controlled trial of 53 primarily White youth between the ages 16-24. The study took place in two hospital-based research clinics in New York City, USA from 2005 to 2010. Youth were assigned randomly to either a 28-day buprenorphine taper (n = 28) or 56-day buprenorphine taper (n = 25). Both groups received behavioral counseling as well as financial incentives in the form of vouchers for recreational activities (e.g., movie tickets) for both opioid abstinence and treatment attendance. Groups were matched to ensure balance on characteristics likely to influence treatment outcomes including gender, age (13-17 vs. 18-24 years), primary past-month route of opioid administration (injection or other), and the availability of a parent/guardian or significant other to participate. To avoid participants knowing what treatment group they were in (i.e., expectancy effects), each participant received the same number of identical-appearing tablets throughout the trial. The amount of active buprenorphine was reduced over the course of the study so that, by the end, each participant was taking only placebo tablets. Both taper groups had a minimum of one week of placebo dosing at the end of the taper. The primary outcome was opioid abstinence measured as a percentage of scheduled urine toxicology tests documented to be negative for opioids. Importantly, for the main analysis, study authors treated missed toxicology screens as positive. In subsequent analyses, they also examined the pattern of results when only administered screens were considered. The secondary outcome was treatment retention, measured as number of days attended scheduled visits.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

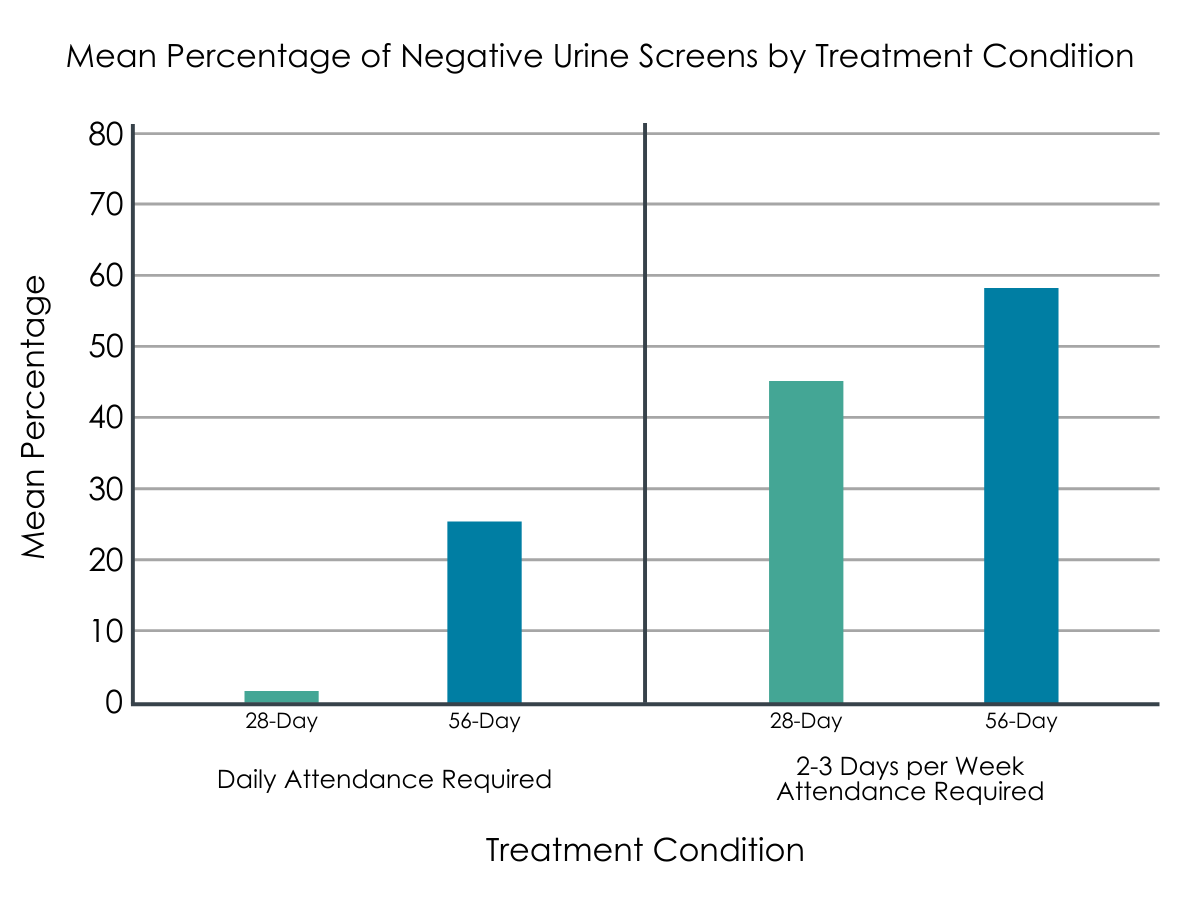

Figure 1. Taken from Marsch et al., 2016: “Mean percentage of urine screens documented as opioid negative by buprenorphine treatment condition before and after changes in attendance requirement”

The longer 56-day taper was associated with significantly greater opioid abstinence in youth with opioid use disorder than the shorter 28-day taper.

Participants in the 56-day condition achieved significantly greater opioid abstinence compared to those in the 28-day condition. That is, youth in the 56-day condition had approximately 35% of scheduled urine screens negative for opioids compared to 17% in the 28-day taper group. Similar differences were observed between the two taper groups when percentage abstinence was based only on the period during which participants remained in treatment (42% vs. 23%) and when based solely on samples obtained (i.e., missing not considered positive; 56% vs. 31%). Importantly, there was evidence that participants in the 56-day taper group had a greater number of days of continuous abstinence from opioids compared to the 28-day taper (16 vs. 7 continuous days).

The longer 56-day taper was associated with significantly greater treatment retention in youth with opioid use disorder than the shorter 28-day taper.

Participants in the 56-day condition were retained in treatment significantly longer than those in the 28-day condition. 36% of participants in the 56-day compared to 18% of those in the 28-day conditions were retained at the end of the 63-day trial. Notably, differences in retention between taper groups were not dependent upon attendance schedule. Overall, 14 of the 53 participants complete the 63-day trail (~74% dropout rate).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This is the first study to compare two different buprenorphine-assisted taper lengths with no period of maintenance among youth with opioid use disorder. Results demonstrate that a longer (56-day) buprenorphine taper produces significantly better abstinence rates and retention outcomes for this population relative to a shorter (28-day) taper. This is a new and important finding, given the limited treatment research conducted with this population. Providing buprenorphine-assisted treatment to youth with opioid use disorder may greatly reduce their likelihood of continued and escalating substance involvement over their lifetime. Currently, no effective standard of care exists for this cohort. Thus, these data may be useful for developing treatment models that promote greater treatment retention, which may help youth benefit more from behavioral treatment and skills training offered within a treatment setting. This perspective is consistent with reviews of the existing treatment literature for youth opioid use disorder. Accordingly, some suggest that given the ongoing opioid epidemic, it may be time for health professionals to consider the use of medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder for their adolescent patients. However, much of the evidence in this area focuses on treatment retention. Thus, as it sits right now, clinicians lack solid evidence to guide them. The debate about whether to prescribe opioid medications to adolescents remains as much philosophical as empirical.

A longer buprenorphine-assisted taper enables a slower opioid reduction in the brains of youth with opioid use disorder. This approach may help stabilize brain chemistry and control withdrawal symptoms more effectively relative to a faster taper. Some concerns have been raised that long-term opioid replacement therapy may lower an adolescent’s likelihood of attaining complete abstinence, and more research is needed to understand the neurological impact that opioid pharmacotherapy can have on youth. However, the risks associated with opioid pharmacotherapy must be weighed against the risks associated with discontinuing opioid pharmacotherapy, such as overdose. While it is likely that buprenorphine maintenance produces better retention and abstinence outcomes than detoxification, if the choice is between differing taper lengths, longer tapers are recommended relative to shorter tapers, as this will probably produce better outcomes. However, it is important to note that, regardless of taper length, most youth did not complete all 63 days of treatment. Lastly, adolescent studies largely involve a combination of behavioral treatment, in addition to the replacement therapy. Thus, any standard of care for opioid replacement therapy with youth should include these behavioral platforms as well.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The sample size in this study was small and, although results are promising, the findings need replication in larger samples. Moreover, there were only 11 youth under the age of 18. However, this population is also difficult to reach, recruit, and retain.

- Participants were self-selected. Youth who self-identify as having a substance use problem and seek treatment may be distinct from youth who have no desire to seek treatment or who are mandated to treatment by criminal justice systems.

- Although results were promising overall, fewer than half of participants enrolled in both conditions completed the entire 63 days of the study. This finding underscores the need to increase the potency of treatment models for youth with opioid use disorder.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study showed that a longer (56-day) buprenorphine taper outperformed a shorter (28-day) taper at increasing opioid abstinence and treatment retention rates in youth with opioid use disorder. This means that such medication for opioid use is effective in youth aged 16-24 and that longer tapers are recommended over shorter ones as this will increase the likelihood of better outcomes. Thus, when investigating treatment options for youth with opioid use disorder, it may be wise to ask pointed questions about the provider’s practice regarding taper lengths, and if providers are uncomfortable with a longer taper it might be in the family’s best interest to seek out alternatives, if/when possible. It is commonplace for practitioners to provide prescriptions for a month’s supply of buprenorphine in the U.S.; thus, this may not be an issue. Also, providers may have differing comfort levels with prescribing buprenorphine to adolescents, despite encouraging evidence. Accordingly, it is important to be an informed consumer and to know the evidence when seeking medical care. Right now, there are promising data to suggest these types of medications have potential to be helpful to adolescents. However, this evidence comes from a limited pool of studies largely focused on treatment retention, and much remains unknown about the long-term consequences on the developing adolescent mind and body.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study showed that a longer (56-day) buprenorphine taper outperformed a shorter (28-day) taper at increasing opioid abstinence and treatment retention rates in youth with opioid use disorder. This means that such medications for opioid use is effective in youth aged 16-24 and that longer tapers are recommended over shorter one as this will increase the likelihood of better outcomes. It is important for treatment professionals to know the effects of different taper lengths on key recovery outcomes in this high-risk group and should be willing to discuss these options with youth seeking treatment for opioid use disorder. That said, there remain many unknowns about opioid use disorder medications with youth and the risks and benefits should be weighed carefully when determining the course of treatment with youth.

- For scientists: This study showed that a longer (56-day) buprenorphine taper outperformed a shorter (28-day) taper at increasing opioid abstinence and treatment retention rates in youth with opioid use disorder. This means that such medication for opioid use is effective in youth aged 16-24 and that longer tapers are recommended over shorter ones, as this will increase the likelihood of better outcomes. Though this is an important finding, there is limited treatment research conducted with this population. Thus, more research is needed to better understand the effects opioid pharmacotherapy can have for youth with opioid use disorder. Additionally, work is needed to determine the long-term effects of this medication on recovery and overall wellbeing later in life. In sum, this area of research warrants urgent scientific attention so that clinicians can better judge the risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy for adolescents with opioid use disorder.

- For policy makers: This study showed that a longer (56-day) buprenorphine taper outperformed a shorter (28-day) taper at increasing opioid abstinence and treatment retention rates in youth with opioid use disorder. This means that such medication for opioid use is effective in youth aged 16-24 and that longer tapers are recommended over shorter one as this will increase the likelihood of better outcomes. It is critical that individuals have access to these life-saving medications, and to this end, access to these medications can be improved by reducing prescription barriers and requiring insurance companies to cover opioid replacement medications. Policy makers should consider investing in the expansion of scientific evidence in this important area, especially in the case of youth, as there is little research to guide policy in this area.

CITATIONS

Marsch, L. A., Moore, S. K., Borodovsky, J. T., Solhkhah, R., Badger, G. J., Semino, S., … & Hajizadeh, N. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of buprenorphine taper duration among opioid‐dependent adolescents and young adults. Addiction, 111(8), 1406-1415. doi: 10.1111/add.13363