One in ten American adults have resolved a significant substance use problem, and half of them identify as being in recovery, yet much less is known about adolescents in this regard. This study investigated the recovery status of adolescents.

One in ten American adults have resolved a significant substance use problem, and half of them identify as being in recovery, yet much less is known about adolescents in this regard. This study investigated the recovery status of adolescents.

l

The impact of alcohol and other substance use on adolescents is especially pronounced given it is a critical developmental period in the human lifespan. Substance use can interfere with healthy biological, emotional, and social development. Although many adolescents engage in substance use, for some, use can quickly escalate from experimentation into use accompanied by consequences that can have long-term effects, such as delayed life transitions (e.g., workforce entry), academic problems (e.g., grades), impaired judgement, later substance use disorders, and injury or death. Many adolescents who use substances naturally reduce or eliminate use (i.e., “age out”) as they get older, which may explain why there is a relative dearth of research on adolescent recovery. Indeed, whether adolescents can or do identify as being in recovery has been questioned.

Among adults, the National Recovery Study found that about 9% of adults have resolved an alcohol or other drug (i.e., substance) use problem and about half of them identify as being in recovery. Factors associated with self-identifying as a person in recovery include history of substance use disorder service utilization and having never been diagnosed with a mental health condition like mood or anxiety disorders. Recovery identity in adults, therefore, may be related to more severe addiction history but without another mental health disorder that might serve as a more salient anchor for their challenges and efforts to overcome them. The prevalence rates of adolescent recovery could aid researchers, practitioners, and policy makers in determining the appropriate funding and resource management to support young people, while factors associated with recovery identity could help inform strategies to better support change for a larger swath of adolescents with substance use disorder. This study of high school students in Illinois estimated the prevalence of recovery status, substance use problem resolution, and correlates of recovery status.

This cross-sectional epidemiological study drew data from the 2020 Illinois Youth Survey, which is designed to survey a representative sample of youth across Illinois and gather information about a variety of health and social indicators. The Illinois Youth Survey is administered to a random sample of schools as well as made available to all schools should they wish to participate. Two different datasets are then created: one that contains only the randomly sampled schools and one that contains both randomly sampled and volunteer schools. However, because the 2020 survey ended earlier than expected due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the anticipated low prevalence of youth in recovery, this study focused on the non-random volunteer sample. A total of 610 out of 1,826 (33%) of eligible schools were included with 60,891 out of 125,067 (49%) students in 9-12th grades. Parental consent for survey participation was sent to all parents prior to data collection, which gave them the choice to opt out of survey participation.

Students answered a variety of questions related to health and wellbeing for the larger study. However, this study drew data from recovery and problem resolution, substance use, and behavioral health questions. Of note, survey instructions stated these questions were specifically related to recovery from substance use. Problem resolution was measured by asking students, “Besides nicotine, did you used to have a problem with drugs or alcohol, but no longer do?” Recovery status was measured by asking, “Do you consider yourself to be in recovery?” These two yes/no questions then created four groups of “recovery status” of adolescents: 1) yes to recovery and yes to problem resolution (“dual status”), 2) recovery only, 3) problem resolution only, and 4) neither recovery nor problem resolution.

Students were also asked about their past 30-day and past year substance use. Responses to substance use were categorized as using on 0 occasions, 1–2 occasions, 3–5 occasions, 6–9 occasions, 10–19 occasions, and 20 or more occasions. Alcohol, marijuana, and prescription drugs “not prescribed to you” were included as well as binge drinking in the past two weeks. Past year substance use questions added inhalants, MDMA/Ecstasy, LSD, cocaine, methamphetamines, heroin, over the-counter drugs, use of prescription painkillers “to get high” and use of other prescription drugs “to get high.” Both past 30-day and past year substance use were dichotomized (10 or more occasions = 1, less than 10 = 0). Students also completed the “CRAFFT”, which is a 6-item screener for substance use disorder among adolescents. They were also asked two questions to elicit depressed mood and suicidal ideation.

In this study, the authors used a statistical approach —called propensity score matching and balancing—designed to produce less biased estimates from observational studies such as this. Since there would likely be very few adolescents with recent substance use, the authors argued that it would be unfair to compare those students that identified as being in recovery or having resolved a substance use problem to all students. Thus, the authors matched students in the neither/nor group with those in the other groups using substance use, conduct problems, behavioral health, race, gender, geographical region, and socioeconomic status (receipt of free and reduced priced lunch). This creates samples that are as similar as possible on the measures mentioned except for the key identifier (i.e., recovery status). The analyses then consisted of comparing each recovery status (dual status, recovery only, problem resolution only) with the matched sample drawn from the neither/nor group.

About half (51%) of the overall sample identified as female, and 47% and 1% identified as male and transgender, respectively. Roughly two-thirds (67%) of students identified as White, followed by Latinx (16%), Asian American (6%), Black (6%), and Other (5%). About 41% of students were in the 10th grade, and 30% were in 12th grade. There were also 15% and 14 % of students in the 9th and 11th grade, respectively. The average age was about 16 years old. About one-third (34%) had free or reduced-price lunch. Most (71%) of the students lived in the suburbs of Chicago, with a very small number (2%) of participating students living in Chicago. The other students lived in another urban setting (15%) or in a rural setting (12%).

Among nearly 70,000 students, 1.4% reported both problem resolution and identified as being in recovery from a substance use problem

Across all student surveys (n = 60,891), 884 (1.4%) reported dual recovery and problem resolution status, 1,546 (2.5%) reported problem resolution only, and 1,811 (2.9%) reported being in recovery only.

The prevalence of past 30-day and past-year substance use was high in the recovery status groups

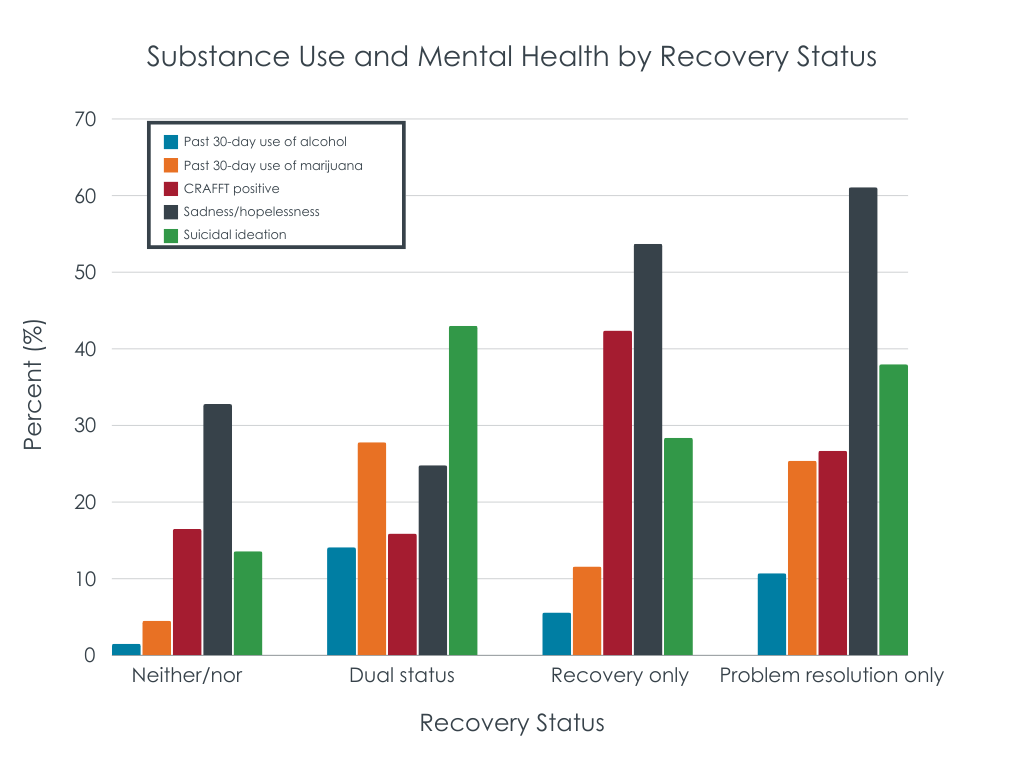

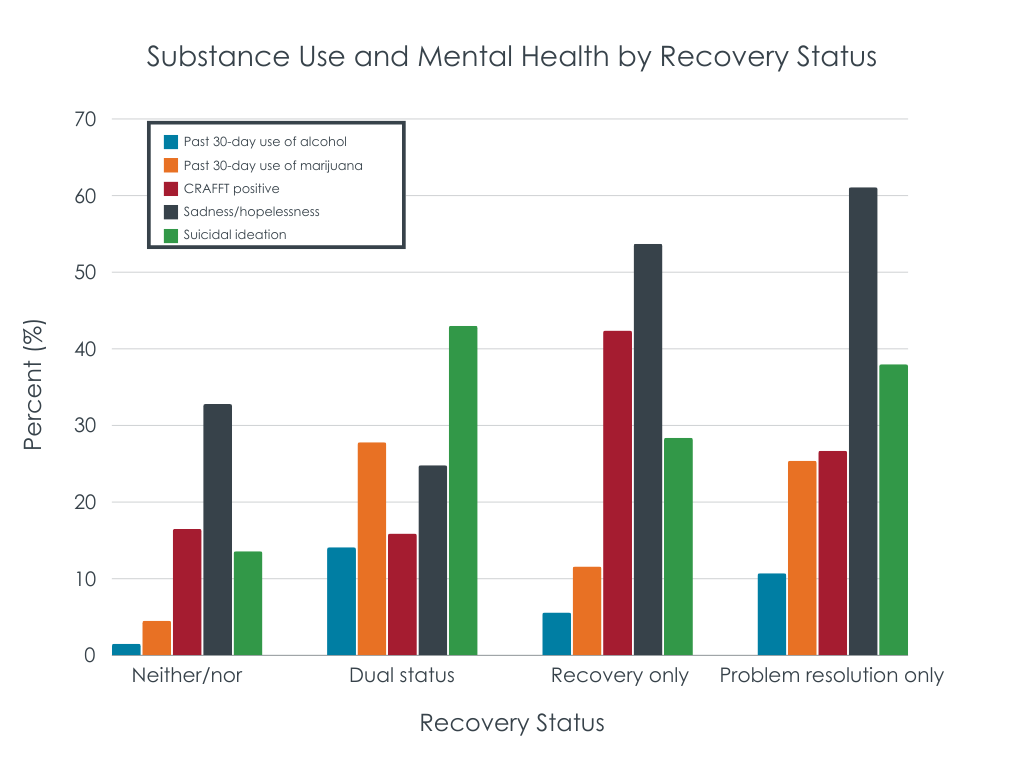

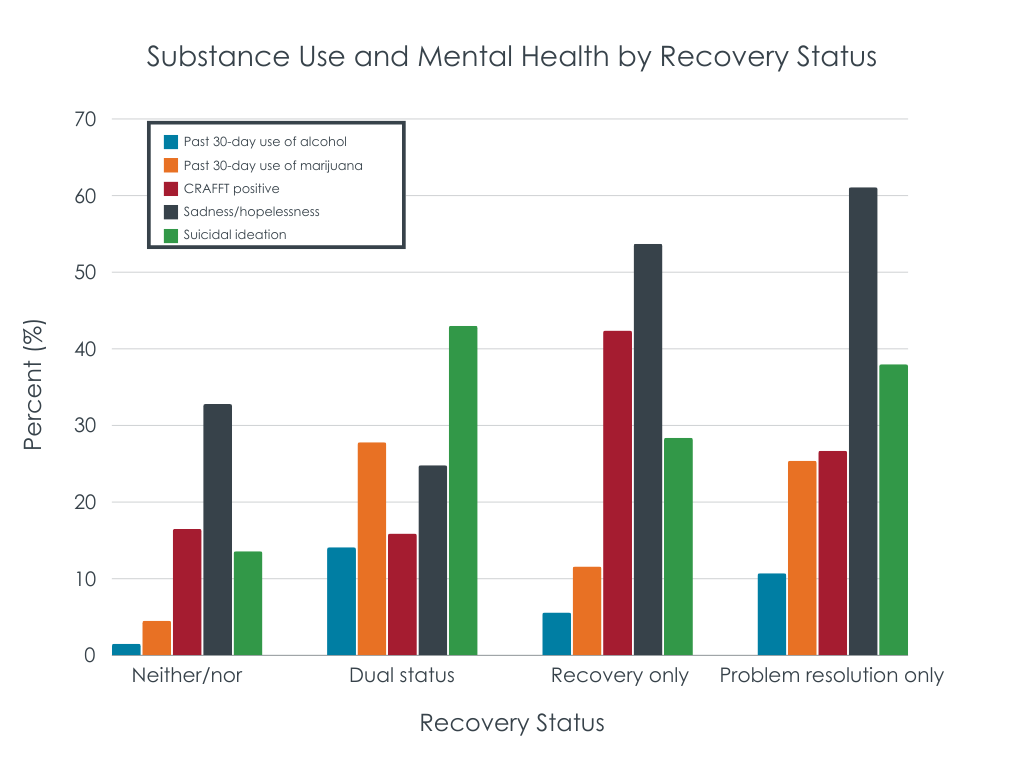

Generally, adolescents that reported being in recovery, resolving a problem, or both, had higher prevalence of substance use and mental health problems compared to matched group of adolescents with no resolution or recovery. There did, however, appear to be differences across recovery groups. The dual status recovery group had the highest rates of past-month substance use, past-year substance to those in the recovery only and neither groups. The problem resolution only group were more similar to the dual status group than the recovery only group.

Figure. Substance use and mental health experiences by group: neither/nor group responded “no” to resolving a substance use problem and to recovery identity; dual status group responded “yes” to both resolving a problem and recovery identity; recovery only group responded “yes” to recovery identity but “no” to resolving a substance use problem; problem resolution only group responded “yes” to resolving a substance use problem but “no” to recovery identity. “CRAFFT”, is a 6-item screener for substance use disorder tailored to adolescents.

However, the researchers did not calculate if these were statistically significant differences. As seen in the figure above, adolescents in the dual status group had the lowest frequency of probable substance use disorder per the CRAFFT score. The adolescents in the dual status group also had the lowest frequency of feeling sad or hopeless in the past two weeks compared to all other groups. This group also had the highest reported levels of suicidal ideation.

Odds of prescription drug use in the past 30 days was lower across recovery and problem resolution groups compared to their matched controls

Adolescents who identified as being in recovery had 26% lower odds of prescription drug use in the last 30 days compared to the matched group of adolescents with no recovery or resolution. Similarly, those in the problem resolution only and dual status group had lower odds of prescription drug use compared to the matched controls as well, with both having 24% lower odds of use compared to their matched control groups. Adolescents in the problem resolution only group also had 12% lower odds of cannabis use in the past 30 days compared to their matched control group. However, the problem resolution only and dual status groups did not. Alcohol use in the past 30 days and binge drinking were not different between any recovery status group and their matched controls.

Researchers in this study investigated the prevalence of recovery status among adolescents in Illinois schools and correlates of that recovery status such as substance use and mental health. Results showed that 1.4% of adolescents identified as being in recovery and having resolved a substance use problem, 2.5% reported only resolving a substance use problem, and 2.9% identified as being in recovery only. So, 4.3% of adolescents shared they identified as being in recovery, if the dual status and recovery only groups were combined. There was a higher prevalence of substance use and mental health problems among adolescents in these three groups compared to those that did not identify as being in recovery or having resolved a substance use problem. A smaller proportion of adolescents (1.4%) identified as being in recovery and having resolved a substance use problem compared to national estimates among adults (4.2%). This is not surprising as adolescents have shorter substance use careers compared to adults. However, if the 1.4% were extrapolated to all adolescents in the United States that would still equate to over 600,000 young people that identify as being in recovery and have resolved a substance use problem.

Of note, participants did not need to report that they resolved a problem in order to respond to the question about recovery identity – as was the procedure in the National Recovery Study. Overall patterns suggest that the problem resolution and dual status group were more similar to one another than to the recovery only group.

Future research will need to help clarify what adolescents understand regarding the concept of recovery, and why some adolescents would identify as in recovery but not having resolved a substance use problem.

Given that returning to use is common, especially for young people, findings here suggest a need for continuing recovery supports that are developmentally appropriate. Adolescents in recovery, in another qualitative study, described how recovery is a journey with stages such as engagement and recovery maintenance. Those same adolescents also emphasized the importance of recovery role models. Thus, stakeholders hoping to support adolescents need to provide environments and opportunities for adolescents in recovery that support their recovery journey. Two types of recovery-specific supports that could aid adolescents are Alternative Peer Groups and Recovery High Schools. Alternative Peer Groups are a comprehensive support that connects recovering peers and prosocial activities into evidenced-based clinical practices. Recovery High Schools are secondary schools for students in recovery from substance use or co-occurring disorders that meet state requirements for awarding a secondary school diploma. Although there are not many studies evaluating these supports, existing work with both Alternative Peer Groups and Recovery High Schools shows their potential benefits for adolescents. Adolescents with substance use problems and in recovery could also be supported in primary care and traditional education settings if these professionals are provided specialized training in addiction and recovery.

In Illinois, this study of students in 9th-12th found that 2.9% were in recovery only, 2.5% reported resolving a substance use problem only and 1.4% of adolescents identified as both having resolved a substance use problem and being in recovery. More work is needed to understand the similarities and differences between adolescent and adult recovery. The prevalence of substance use problems and recovery identities among adolescents does suggest developmentally tailored recovery supports are needed.

Smith, D. C., Reinhart, C. A., Begum, S., Kosgolla, J., Kelly, J. F., Bergman, B. G., & Basic, M. (2023). Coming of age in recovery: The prevalence and correlates of substance use recovery status among adolescents and emerging adults. PLOS ONE, 18(12), e0295330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0295330

l

The impact of alcohol and other substance use on adolescents is especially pronounced given it is a critical developmental period in the human lifespan. Substance use can interfere with healthy biological, emotional, and social development. Although many adolescents engage in substance use, for some, use can quickly escalate from experimentation into use accompanied by consequences that can have long-term effects, such as delayed life transitions (e.g., workforce entry), academic problems (e.g., grades), impaired judgement, later substance use disorders, and injury or death. Many adolescents who use substances naturally reduce or eliminate use (i.e., “age out”) as they get older, which may explain why there is a relative dearth of research on adolescent recovery. Indeed, whether adolescents can or do identify as being in recovery has been questioned.

Among adults, the National Recovery Study found that about 9% of adults have resolved an alcohol or other drug (i.e., substance) use problem and about half of them identify as being in recovery. Factors associated with self-identifying as a person in recovery include history of substance use disorder service utilization and having never been diagnosed with a mental health condition like mood or anxiety disorders. Recovery identity in adults, therefore, may be related to more severe addiction history but without another mental health disorder that might serve as a more salient anchor for their challenges and efforts to overcome them. The prevalence rates of adolescent recovery could aid researchers, practitioners, and policy makers in determining the appropriate funding and resource management to support young people, while factors associated with recovery identity could help inform strategies to better support change for a larger swath of adolescents with substance use disorder. This study of high school students in Illinois estimated the prevalence of recovery status, substance use problem resolution, and correlates of recovery status.

This cross-sectional epidemiological study drew data from the 2020 Illinois Youth Survey, which is designed to survey a representative sample of youth across Illinois and gather information about a variety of health and social indicators. The Illinois Youth Survey is administered to a random sample of schools as well as made available to all schools should they wish to participate. Two different datasets are then created: one that contains only the randomly sampled schools and one that contains both randomly sampled and volunteer schools. However, because the 2020 survey ended earlier than expected due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the anticipated low prevalence of youth in recovery, this study focused on the non-random volunteer sample. A total of 610 out of 1,826 (33%) of eligible schools were included with 60,891 out of 125,067 (49%) students in 9-12th grades. Parental consent for survey participation was sent to all parents prior to data collection, which gave them the choice to opt out of survey participation.

Students answered a variety of questions related to health and wellbeing for the larger study. However, this study drew data from recovery and problem resolution, substance use, and behavioral health questions. Of note, survey instructions stated these questions were specifically related to recovery from substance use. Problem resolution was measured by asking students, “Besides nicotine, did you used to have a problem with drugs or alcohol, but no longer do?” Recovery status was measured by asking, “Do you consider yourself to be in recovery?” These two yes/no questions then created four groups of “recovery status” of adolescents: 1) yes to recovery and yes to problem resolution (“dual status”), 2) recovery only, 3) problem resolution only, and 4) neither recovery nor problem resolution.

Students were also asked about their past 30-day and past year substance use. Responses to substance use were categorized as using on 0 occasions, 1–2 occasions, 3–5 occasions, 6–9 occasions, 10–19 occasions, and 20 or more occasions. Alcohol, marijuana, and prescription drugs “not prescribed to you” were included as well as binge drinking in the past two weeks. Past year substance use questions added inhalants, MDMA/Ecstasy, LSD, cocaine, methamphetamines, heroin, over the-counter drugs, use of prescription painkillers “to get high” and use of other prescription drugs “to get high.” Both past 30-day and past year substance use were dichotomized (10 or more occasions = 1, less than 10 = 0). Students also completed the “CRAFFT”, which is a 6-item screener for substance use disorder among adolescents. They were also asked two questions to elicit depressed mood and suicidal ideation.

In this study, the authors used a statistical approach —called propensity score matching and balancing—designed to produce less biased estimates from observational studies such as this. Since there would likely be very few adolescents with recent substance use, the authors argued that it would be unfair to compare those students that identified as being in recovery or having resolved a substance use problem to all students. Thus, the authors matched students in the neither/nor group with those in the other groups using substance use, conduct problems, behavioral health, race, gender, geographical region, and socioeconomic status (receipt of free and reduced priced lunch). This creates samples that are as similar as possible on the measures mentioned except for the key identifier (i.e., recovery status). The analyses then consisted of comparing each recovery status (dual status, recovery only, problem resolution only) with the matched sample drawn from the neither/nor group.

About half (51%) of the overall sample identified as female, and 47% and 1% identified as male and transgender, respectively. Roughly two-thirds (67%) of students identified as White, followed by Latinx (16%), Asian American (6%), Black (6%), and Other (5%). About 41% of students were in the 10th grade, and 30% were in 12th grade. There were also 15% and 14 % of students in the 9th and 11th grade, respectively. The average age was about 16 years old. About one-third (34%) had free or reduced-price lunch. Most (71%) of the students lived in the suburbs of Chicago, with a very small number (2%) of participating students living in Chicago. The other students lived in another urban setting (15%) or in a rural setting (12%).

Among nearly 70,000 students, 1.4% reported both problem resolution and identified as being in recovery from a substance use problem

Across all student surveys (n = 60,891), 884 (1.4%) reported dual recovery and problem resolution status, 1,546 (2.5%) reported problem resolution only, and 1,811 (2.9%) reported being in recovery only.

The prevalence of past 30-day and past-year substance use was high in the recovery status groups

Generally, adolescents that reported being in recovery, resolving a problem, or both, had higher prevalence of substance use and mental health problems compared to matched group of adolescents with no resolution or recovery. There did, however, appear to be differences across recovery groups. The dual status recovery group had the highest rates of past-month substance use, past-year substance to those in the recovery only and neither groups. The problem resolution only group were more similar to the dual status group than the recovery only group.

Figure. Substance use and mental health experiences by group: neither/nor group responded “no” to resolving a substance use problem and to recovery identity; dual status group responded “yes” to both resolving a problem and recovery identity; recovery only group responded “yes” to recovery identity but “no” to resolving a substance use problem; problem resolution only group responded “yes” to resolving a substance use problem but “no” to recovery identity. “CRAFFT”, is a 6-item screener for substance use disorder tailored to adolescents.

However, the researchers did not calculate if these were statistically significant differences. As seen in the figure above, adolescents in the dual status group had the lowest frequency of probable substance use disorder per the CRAFFT score. The adolescents in the dual status group also had the lowest frequency of feeling sad or hopeless in the past two weeks compared to all other groups. This group also had the highest reported levels of suicidal ideation.

Odds of prescription drug use in the past 30 days was lower across recovery and problem resolution groups compared to their matched controls

Adolescents who identified as being in recovery had 26% lower odds of prescription drug use in the last 30 days compared to the matched group of adolescents with no recovery or resolution. Similarly, those in the problem resolution only and dual status group had lower odds of prescription drug use compared to the matched controls as well, with both having 24% lower odds of use compared to their matched control groups. Adolescents in the problem resolution only group also had 12% lower odds of cannabis use in the past 30 days compared to their matched control group. However, the problem resolution only and dual status groups did not. Alcohol use in the past 30 days and binge drinking were not different between any recovery status group and their matched controls.

Researchers in this study investigated the prevalence of recovery status among adolescents in Illinois schools and correlates of that recovery status such as substance use and mental health. Results showed that 1.4% of adolescents identified as being in recovery and having resolved a substance use problem, 2.5% reported only resolving a substance use problem, and 2.9% identified as being in recovery only. So, 4.3% of adolescents shared they identified as being in recovery, if the dual status and recovery only groups were combined. There was a higher prevalence of substance use and mental health problems among adolescents in these three groups compared to those that did not identify as being in recovery or having resolved a substance use problem. A smaller proportion of adolescents (1.4%) identified as being in recovery and having resolved a substance use problem compared to national estimates among adults (4.2%). This is not surprising as adolescents have shorter substance use careers compared to adults. However, if the 1.4% were extrapolated to all adolescents in the United States that would still equate to over 600,000 young people that identify as being in recovery and have resolved a substance use problem.

Of note, participants did not need to report that they resolved a problem in order to respond to the question about recovery identity – as was the procedure in the National Recovery Study. Overall patterns suggest that the problem resolution and dual status group were more similar to one another than to the recovery only group.

Future research will need to help clarify what adolescents understand regarding the concept of recovery, and why some adolescents would identify as in recovery but not having resolved a substance use problem.

Given that returning to use is common, especially for young people, findings here suggest a need for continuing recovery supports that are developmentally appropriate. Adolescents in recovery, in another qualitative study, described how recovery is a journey with stages such as engagement and recovery maintenance. Those same adolescents also emphasized the importance of recovery role models. Thus, stakeholders hoping to support adolescents need to provide environments and opportunities for adolescents in recovery that support their recovery journey. Two types of recovery-specific supports that could aid adolescents are Alternative Peer Groups and Recovery High Schools. Alternative Peer Groups are a comprehensive support that connects recovering peers and prosocial activities into evidenced-based clinical practices. Recovery High Schools are secondary schools for students in recovery from substance use or co-occurring disorders that meet state requirements for awarding a secondary school diploma. Although there are not many studies evaluating these supports, existing work with both Alternative Peer Groups and Recovery High Schools shows their potential benefits for adolescents. Adolescents with substance use problems and in recovery could also be supported in primary care and traditional education settings if these professionals are provided specialized training in addiction and recovery.

In Illinois, this study of students in 9th-12th found that 2.9% were in recovery only, 2.5% reported resolving a substance use problem only and 1.4% of adolescents identified as both having resolved a substance use problem and being in recovery. More work is needed to understand the similarities and differences between adolescent and adult recovery. The prevalence of substance use problems and recovery identities among adolescents does suggest developmentally tailored recovery supports are needed.

Smith, D. C., Reinhart, C. A., Begum, S., Kosgolla, J., Kelly, J. F., Bergman, B. G., & Basic, M. (2023). Coming of age in recovery: The prevalence and correlates of substance use recovery status among adolescents and emerging adults. PLOS ONE, 18(12), e0295330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0295330

l

The impact of alcohol and other substance use on adolescents is especially pronounced given it is a critical developmental period in the human lifespan. Substance use can interfere with healthy biological, emotional, and social development. Although many adolescents engage in substance use, for some, use can quickly escalate from experimentation into use accompanied by consequences that can have long-term effects, such as delayed life transitions (e.g., workforce entry), academic problems (e.g., grades), impaired judgement, later substance use disorders, and injury or death. Many adolescents who use substances naturally reduce or eliminate use (i.e., “age out”) as they get older, which may explain why there is a relative dearth of research on adolescent recovery. Indeed, whether adolescents can or do identify as being in recovery has been questioned.

Among adults, the National Recovery Study found that about 9% of adults have resolved an alcohol or other drug (i.e., substance) use problem and about half of them identify as being in recovery. Factors associated with self-identifying as a person in recovery include history of substance use disorder service utilization and having never been diagnosed with a mental health condition like mood or anxiety disorders. Recovery identity in adults, therefore, may be related to more severe addiction history but without another mental health disorder that might serve as a more salient anchor for their challenges and efforts to overcome them. The prevalence rates of adolescent recovery could aid researchers, practitioners, and policy makers in determining the appropriate funding and resource management to support young people, while factors associated with recovery identity could help inform strategies to better support change for a larger swath of adolescents with substance use disorder. This study of high school students in Illinois estimated the prevalence of recovery status, substance use problem resolution, and correlates of recovery status.

This cross-sectional epidemiological study drew data from the 2020 Illinois Youth Survey, which is designed to survey a representative sample of youth across Illinois and gather information about a variety of health and social indicators. The Illinois Youth Survey is administered to a random sample of schools as well as made available to all schools should they wish to participate. Two different datasets are then created: one that contains only the randomly sampled schools and one that contains both randomly sampled and volunteer schools. However, because the 2020 survey ended earlier than expected due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the anticipated low prevalence of youth in recovery, this study focused on the non-random volunteer sample. A total of 610 out of 1,826 (33%) of eligible schools were included with 60,891 out of 125,067 (49%) students in 9-12th grades. Parental consent for survey participation was sent to all parents prior to data collection, which gave them the choice to opt out of survey participation.

Students answered a variety of questions related to health and wellbeing for the larger study. However, this study drew data from recovery and problem resolution, substance use, and behavioral health questions. Of note, survey instructions stated these questions were specifically related to recovery from substance use. Problem resolution was measured by asking students, “Besides nicotine, did you used to have a problem with drugs or alcohol, but no longer do?” Recovery status was measured by asking, “Do you consider yourself to be in recovery?” These two yes/no questions then created four groups of “recovery status” of adolescents: 1) yes to recovery and yes to problem resolution (“dual status”), 2) recovery only, 3) problem resolution only, and 4) neither recovery nor problem resolution.

Students were also asked about their past 30-day and past year substance use. Responses to substance use were categorized as using on 0 occasions, 1–2 occasions, 3–5 occasions, 6–9 occasions, 10–19 occasions, and 20 or more occasions. Alcohol, marijuana, and prescription drugs “not prescribed to you” were included as well as binge drinking in the past two weeks. Past year substance use questions added inhalants, MDMA/Ecstasy, LSD, cocaine, methamphetamines, heroin, over the-counter drugs, use of prescription painkillers “to get high” and use of other prescription drugs “to get high.” Both past 30-day and past year substance use were dichotomized (10 or more occasions = 1, less than 10 = 0). Students also completed the “CRAFFT”, which is a 6-item screener for substance use disorder among adolescents. They were also asked two questions to elicit depressed mood and suicidal ideation.

In this study, the authors used a statistical approach —called propensity score matching and balancing—designed to produce less biased estimates from observational studies such as this. Since there would likely be very few adolescents with recent substance use, the authors argued that it would be unfair to compare those students that identified as being in recovery or having resolved a substance use problem to all students. Thus, the authors matched students in the neither/nor group with those in the other groups using substance use, conduct problems, behavioral health, race, gender, geographical region, and socioeconomic status (receipt of free and reduced priced lunch). This creates samples that are as similar as possible on the measures mentioned except for the key identifier (i.e., recovery status). The analyses then consisted of comparing each recovery status (dual status, recovery only, problem resolution only) with the matched sample drawn from the neither/nor group.

About half (51%) of the overall sample identified as female, and 47% and 1% identified as male and transgender, respectively. Roughly two-thirds (67%) of students identified as White, followed by Latinx (16%), Asian American (6%), Black (6%), and Other (5%). About 41% of students were in the 10th grade, and 30% were in 12th grade. There were also 15% and 14 % of students in the 9th and 11th grade, respectively. The average age was about 16 years old. About one-third (34%) had free or reduced-price lunch. Most (71%) of the students lived in the suburbs of Chicago, with a very small number (2%) of participating students living in Chicago. The other students lived in another urban setting (15%) or in a rural setting (12%).

Among nearly 70,000 students, 1.4% reported both problem resolution and identified as being in recovery from a substance use problem

Across all student surveys (n = 60,891), 884 (1.4%) reported dual recovery and problem resolution status, 1,546 (2.5%) reported problem resolution only, and 1,811 (2.9%) reported being in recovery only.

The prevalence of past 30-day and past-year substance use was high in the recovery status groups

Generally, adolescents that reported being in recovery, resolving a problem, or both, had higher prevalence of substance use and mental health problems compared to matched group of adolescents with no resolution or recovery. There did, however, appear to be differences across recovery groups. The dual status recovery group had the highest rates of past-month substance use, past-year substance to those in the recovery only and neither groups. The problem resolution only group were more similar to the dual status group than the recovery only group.

Figure. Substance use and mental health experiences by group: neither/nor group responded “no” to resolving a substance use problem and to recovery identity; dual status group responded “yes” to both resolving a problem and recovery identity; recovery only group responded “yes” to recovery identity but “no” to resolving a substance use problem; problem resolution only group responded “yes” to resolving a substance use problem but “no” to recovery identity. “CRAFFT”, is a 6-item screener for substance use disorder tailored to adolescents.

However, the researchers did not calculate if these were statistically significant differences. As seen in the figure above, adolescents in the dual status group had the lowest frequency of probable substance use disorder per the CRAFFT score. The adolescents in the dual status group also had the lowest frequency of feeling sad or hopeless in the past two weeks compared to all other groups. This group also had the highest reported levels of suicidal ideation.

Odds of prescription drug use in the past 30 days was lower across recovery and problem resolution groups compared to their matched controls

Adolescents who identified as being in recovery had 26% lower odds of prescription drug use in the last 30 days compared to the matched group of adolescents with no recovery or resolution. Similarly, those in the problem resolution only and dual status group had lower odds of prescription drug use compared to the matched controls as well, with both having 24% lower odds of use compared to their matched control groups. Adolescents in the problem resolution only group also had 12% lower odds of cannabis use in the past 30 days compared to their matched control group. However, the problem resolution only and dual status groups did not. Alcohol use in the past 30 days and binge drinking were not different between any recovery status group and their matched controls.

Researchers in this study investigated the prevalence of recovery status among adolescents in Illinois schools and correlates of that recovery status such as substance use and mental health. Results showed that 1.4% of adolescents identified as being in recovery and having resolved a substance use problem, 2.5% reported only resolving a substance use problem, and 2.9% identified as being in recovery only. So, 4.3% of adolescents shared they identified as being in recovery, if the dual status and recovery only groups were combined. There was a higher prevalence of substance use and mental health problems among adolescents in these three groups compared to those that did not identify as being in recovery or having resolved a substance use problem. A smaller proportion of adolescents (1.4%) identified as being in recovery and having resolved a substance use problem compared to national estimates among adults (4.2%). This is not surprising as adolescents have shorter substance use careers compared to adults. However, if the 1.4% were extrapolated to all adolescents in the United States that would still equate to over 600,000 young people that identify as being in recovery and have resolved a substance use problem.

Of note, participants did not need to report that they resolved a problem in order to respond to the question about recovery identity – as was the procedure in the National Recovery Study. Overall patterns suggest that the problem resolution and dual status group were more similar to one another than to the recovery only group.

Future research will need to help clarify what adolescents understand regarding the concept of recovery, and why some adolescents would identify as in recovery but not having resolved a substance use problem.

Given that returning to use is common, especially for young people, findings here suggest a need for continuing recovery supports that are developmentally appropriate. Adolescents in recovery, in another qualitative study, described how recovery is a journey with stages such as engagement and recovery maintenance. Those same adolescents also emphasized the importance of recovery role models. Thus, stakeholders hoping to support adolescents need to provide environments and opportunities for adolescents in recovery that support their recovery journey. Two types of recovery-specific supports that could aid adolescents are Alternative Peer Groups and Recovery High Schools. Alternative Peer Groups are a comprehensive support that connects recovering peers and prosocial activities into evidenced-based clinical practices. Recovery High Schools are secondary schools for students in recovery from substance use or co-occurring disorders that meet state requirements for awarding a secondary school diploma. Although there are not many studies evaluating these supports, existing work with both Alternative Peer Groups and Recovery High Schools shows their potential benefits for adolescents. Adolescents with substance use problems and in recovery could also be supported in primary care and traditional education settings if these professionals are provided specialized training in addiction and recovery.

In Illinois, this study of students in 9th-12th found that 2.9% were in recovery only, 2.5% reported resolving a substance use problem only and 1.4% of adolescents identified as both having resolved a substance use problem and being in recovery. More work is needed to understand the similarities and differences between adolescent and adult recovery. The prevalence of substance use problems and recovery identities among adolescents does suggest developmentally tailored recovery supports are needed.

Smith, D. C., Reinhart, C. A., Begum, S., Kosgolla, J., Kelly, J. F., Bergman, B. G., & Basic, M. (2023). Coming of age in recovery: The prevalence and correlates of substance use recovery status among adolescents and emerging adults. PLOS ONE, 18(12), e0295330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0295330