Can Involving Family Members & Friends Enhance Brief Hospital-based Interventions?

Individuals’ readiness to make changes in their substance use tends to wax and wane over time, often depending on the consequences of use.

Hospitals provide a setting where current motivation to reduce or quit drinking is strong because patients may be there directly because of the negative consequences of their drinking. These encounters provide an opportunity to begin a conversation about alcohol-related harms and help them consider changing their drinking.

Thus far, results from studies of these types of interventions have shown promise though with somewhat mixed, and relatively modest, effects. Separately, research highlights the importance of recovery social support, and of pro-recovery versus pro-drinking individuals in one’s social network, in predicting who will cut back or stop drinking.

Monti and colleagues examined whether including a significant other (SO) in the brief intervention could enhance its impact on problem drinkers in a hospital setting.

Participants (N = 414) who were admitted to the emergency department or trauma unit at a Level I trauma unit in the United States, were randomized to receive either an individual brief motivational intervention (IMI; n = 193) or a significant “other-enhanced” brief motivational intervention (SOMI; n = 210), and assessed at admission (i.e., baseline) as well as 6-month and 12-month follow-ups. A control group was not included because it was deemed unethical to withhold treatment to a group of patients requiring acute medical care.

To be included, participants needed to either a) meet the clinical cutoff for the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification test (8 or more; M AUDIT score for the sample = 15), b) have a blood alcohol level of .01 or higher at admission, or c) report alcohol use no more than 6 hours before the event leading to their admission, and be able to identify a significant other to participate in the study (46 were excluded due to this final criterion). Participants were about 70% male and 33 years old on average, mostly high-school educated, and were diverse with respect to ethnicity (68% Caucasian, 19% African American, 16% Hispanic, and 14% other or multiracial).

Significant others were 70% female, and typically a romantic partner (39%), family member (30%), or friend (30%). All significant others completed study measures irrespective of whether they were involved in the intervention. Note that due to challenges of providing addiction treatment in a real-world clinical setting, the sample on which the authors conducted analyses was lower than this initial sample of 414, ranging from 370 to 375.

Both interventions consisted of a single session (lasting about 50 minutes), where a masters or doctoral level clinician used a motivational interviewing approach to facilitate discussion of pros/cons of drinking, personalized feedback on the participant’s current drinking behaviors relative to other individuals in the United States, and risky activities associated with their drinking.

Significant “other-enhanced” brief motivational intervention (SOMI) was different from individual brief motivational intervention (IMI) in that the significant other was present, their perspectives on the patient’s drinking were elicited, and they were involved in the motivational exercises. Review of session audio tapes showed that clinician’s faithfulness to the intervention as planned was strong. Primary outcomes examined were drinks per week, heavy drinking days (5+ or 4+ drinks in one day for men and women, respectively), and drinking related consequences and how significant others responded to participants’ drinking or abstinence over time.

Authors found that all participants reduced weekly drinking, while Significant “other-enhanced” brief motivational intervention (SOMI) participants had greater reductions though not until 12-month follow-up.

Those receiving Significant “other-enhanced” brief motivational intervention (SOMI) in the trauma unit had even greater reductions than those in the emergency department, likely explained by more severe consequences requiring a trauma-unit admission as observed in their greater motivation to reduce drinking on admission.

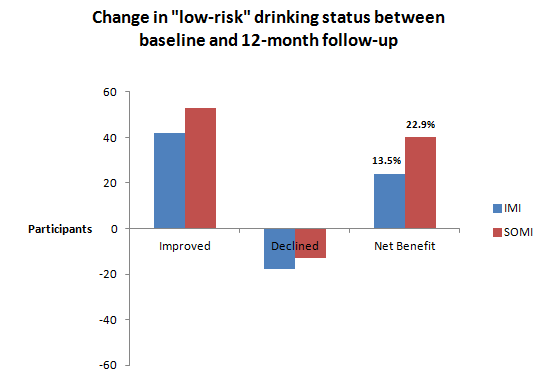

Authors also ran analyses to examine the clinical (or practical) significance of findings, using the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism guidelines of 14 or fewer and 7 or fewer drinks for men and women, respectively, as a proxy for “low risk” drinking.

Specifically, results showed that for every 11 patients treated, using SOMI versus IMI would result in 1 more participant who experiences a meaningful improvement in drinking. Although all participants improved heavy drinking days and drinking related consequences, there was no advantage for either intervention. Interestingly, all participants and their significant others generally reported improvements in significant other’s response to participant drinking (e.g., decrease in support for drinking), irrespective of which intervention the participant received.

IN CONTEXT

This study is an important addition to the literature on brief interventions in examining whether involving a significant other can enhance treatment outcomes.

This adds to several other interventions that show benefit of leveraging the role of a significant other (see here) or including a significant other in treatment (see here).

Given the tremendous public health impact of alcohol misuse, even a small benefit produced by involving a significant other in a hospital-based brief intervention may be meaningful when considered on a large scale.

- LIMITATIONS

-

Note that observed reductions in drinking, even in the SOMI, trauma-unit participants were considered relatively modest. In addition, all participants had an involved significant other in the study (though they only completed assessments in the IMI condition), which may have positively influenced even the IMI participants, ultimately muting the benefit for SOMI. Finally, the study used specially trained doctoral and masters level clinicians, which may not be feasible in all hospital settings.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: The hospital setting could be an opportune time to change drinking habits, and involving a a romantic partner, family member, or friend could support thoughts or actions toward change.

- For scientists: As with prior studies on brief interventions, results were not consistent across outcomes, whereby SOMI appeared to provide extra benefit relative to IMI, but only for weekly drinks, not for heavy drinking days or drinking related consequences. Future research should continue to examine SOMI as well as other ways to enhance brief interventions. As authors suggest, the next step could be a cost-benefit analysis of money saved as a function of reduced drinking and costs of specialized service provision in these settings.

- For policy makers: Consider an initiative to provide patients admitted due to drinking related events, or demonstrating problem drinking in some way, with a specialized brief motivational intervention. At present, it is unclear whether involving a significant other is worth the added cost.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: If feasible, hospitals may wish to employ specially trained staff to engage patients with alcohol-related admissions in brief motivational interventions.

CITATIONS

Monti, P. M., Colby, S. M., Mastroleo, N. R., Barnett, N. P., Gwaltney, C. J., Apodaca, T. R., … & Biffl, W. L. (2014). Individual versus significant-other-enhanced brief motivational intervention for alcohol in emergency care. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 82(6), 936.