Can a popular measure of impulsivity be used to understand recovery?

In spite of its good long-term prognosis, individuals with substance use disorder typically make multiple attempts to change before achieving sustained recovery. Tools that can help clinicians and recovery support staff identify relapse risk earlier may help prevent relapse and recurrence of use while reducing any associated harms. To explore its suitability as a marker of recovery over time, researchers examined the relationship between a widely used measure of impulsivity and perceived risk for relapse.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Although the majority of people seeking recovery from substance use disorder eventually achieve full sustained remission, it often takes people multiple attempts to get there. This accounts for the high relapse rates estimated to be about 40 to 60%. Developing tools or metrics that could be used to predict relapse offers the opportunity to identify and preempt this risk.

Delay discounting is a commonly used measure of impulsivity and is defined as the tendency to overvalue smaller immediate rewards over larger later rewards. Quite literally, it is the inclination to discount rewards that are delayed. Practically speaking, all human beings have this tendency but people with addiction tend to exhibit more of it. In fact, delay discounting is often thought of as a behavioral marker of addiction – individuals may engage in substance use for its immediate rewarding effects with less consideration of its long-term consequences and the future benefits of abstaining. Indeed, delayed discounting is related to both the presence of substance use disorder and how individuals might fare in addiction treatment.

One measure of delay discounting is derived from a task that asks participants to hypothetically choose between an immediate $500 reward, and a delayed $1,000 reward. The delay typically starts at 3 weeks and either increases or decreases in subsequent trials depending on the participant’s initial choice. Responses are used to calculate a discounting rate for each participant. A higher discounting rate indicates that a participant devalued the larger future rewards to a greater degree- a marker of greater impulsivity.

Delay discounting example: Choosing a smaller immediate reward vs. a larger later reward.

The authors of this paper have previously shown that lower rates of discounting (i.e., less impulsivity), and higher abstinence self-efficacy (i.e., greater confidence to remain abstinent) were associated with longer recovery durations (i.e., more days of continuous abstinence). In this study, they explored the relationship between delay discounting and perceived risk of relapse among those in long-term substance use disorder recovery.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a cross-sectional study with 193 individuals self-identifying as being in recovery from substance misuse who were participating in the International Quit and Recovery Registry, an ongoing online registry that aims to study the recovery process and its different domains and phenotypes through monthly assessment of participants.

Participants’ delay discounting was assessed using the delay discounting task described above. Perceived relapse risk was measured using the Advance WArning of RElapse (AWARE) measure, a 28-item scale in which participants are asked, on a 7-point scale from “never” to “always”, how often they have feelings and thoughts that have been shown to contribute to relapse, such as “I think about using my drug of addiction”, and “I feel nervous or unsure of my ability to stay sober”.

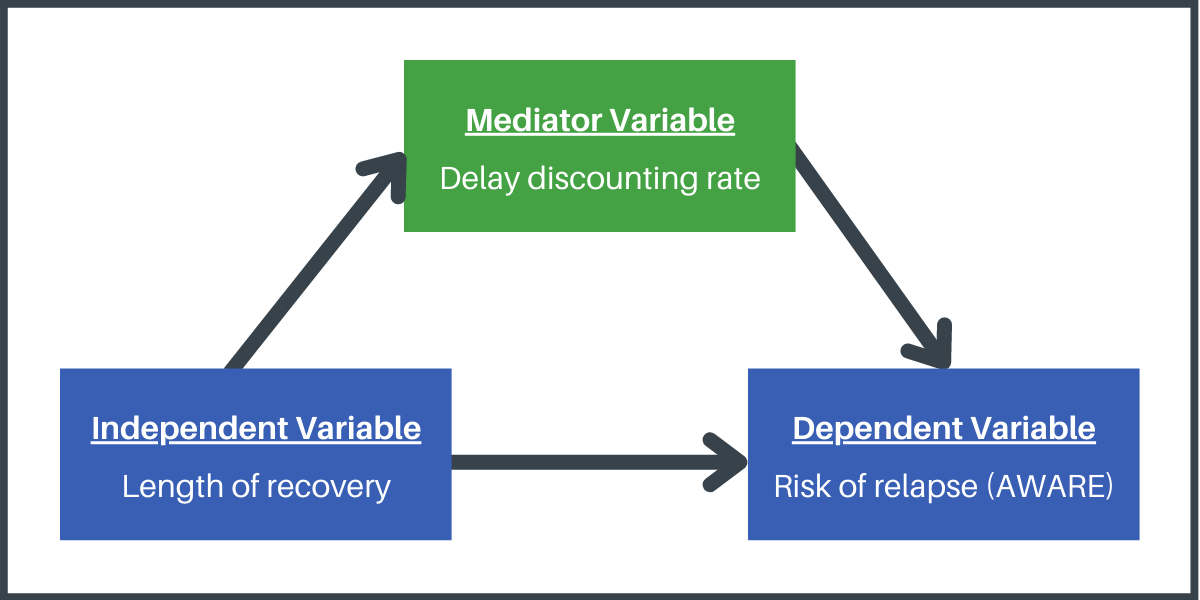

The researchers explored the relationship between delay discounting and perceived relapse risk using linear regression, controlling for individual factors including age, gender, education level, marital status, ethnicity, race, primary substance, and length in the registry. In addition, the researchers conducted a mediation analysis to explore the degree to which the delay discounting rate explains the association between time in recovery and the perceived risk of relapse – two variables that are usually inversely related.

Of the 193 participants, 62.4% reported alcohol as their primary substance of misuse, 12.4% opioids, and 25.2% stimulants and others. The average age was 44.7, and the sample was 59.8% female and predominantly White (79.3%). On average, participants identified as being in recovery for 8.9 years with 4.3 relapses. Of the 193 participants, 9.8% reported ongoing substance use.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Greater delay discounting was associated with greater perceived risk for relapse and less time in recovery.

Controlling for the demographic and other variables described above, the researchers found that greater level of delay discounting was uniquely associated with less time in recovery. They also found, controlling for the same set of variables, that greater levels of delay discounting was associated with greater perceived relapse risk.

Delay discounting partially explained the relationship between length of recovery and perceived risk for relapse.

The mediation analysis results indicated that the relationship between length of recovery and perceived risk for relapse was in part being driven by participant’s impulsivity measured by delay discounting. Overall, the discounting rates accounted for 21.2% of the total effect between the length of recovery and the perceived risk of relapse. This can be interpreted to mean that 21% of the relationship between participants’ length of recovery and the perceived risk of relapse was accounted for by the effects the delay discounting task was capturing (i.e., impulsivity).

Theoretical pathway researchers identified about the effect of delay discounting on risk of relapse. A statistically significant effect was found wherein delay discounting accounted for 21% of the total effect between length of recovery and risk of relapse.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Delay discounting is thought of as a transdiagnostic marker for a range of psychological disorders. In particular, it is believed to capture the impulsivity and difficulty delaying reward that is central to the addictive process.

The researchers found that for individuals in substance use disorder recovery, greater delay discounting was associated with a greater perceived relapse risk. This finding is consistent with previous research, indicating that greater delay discounting rates at baseline are associated with an actual increased likelihood of smoking relapse at a 6-month follow-up, showing a similar relationship between delay discounting and perceived risk of relapse among individuals in substance use disorder recovery for varying lengths of time..

They also found that delay discounting helped to explain the relationship between longer time in recovery and reduced (perceived) relapse risk. While this is a hypothesis, based on the theory that decreases in delay discounting over time is an important marker of enhanced recovery, these findings cannot definitively support or refute this hypothesis, given the cross-sectional nature of the data. But the pattern of statistical relationships between delay discounting, time in recovery, and perceived relapse risk, were supportive of it and suggest it is worthy of further study in longitudinal research. Following the same people over time can help researchers determine the recovery processes that initially predict changes in delayed discounting and whether these beneficial changes, in turn, predict decreased likelihood of recurrence of substance use symptoms and relapse.

It is important to note that there are many other identified and suspected biological, psychological, and social factors that also influence risk for relapse. After all, delay discounting only explained about 21% of this effect indicating there are other very important factors that also explain this relationship. To understand the unique and added value of studying and addressing delay discounting to enhance recovery for individuals with substance use disorder, it should be studied alongside other known psychosocial mechanisms of behavior change, and other markers of improved recovery (e.g., decreased substance use and enhanced health and well-being), such as changes in motivation, coping skills, abstinence self-efficacy, and social network changes. It is possible, for example, that delay discounting represents a separate and specific recovery process that can be addressed (e.g., through treatment) and improved. It is also possible that delay discounting is better labeled as a marker of the recovery process that reflects improvements along with these other known mechanisms of recovery-related behavior change.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the researchers:

- These data come from an online sample of individuals who selected to participate and may not generalize to the population of individuals in SUD recovery.

- The relationship between the perceived risk of relapse and length of recovery was only partially mediated by delay discounting. Other factors exist that have the potential to confound effects that were not assessed in this study (e.g., severity of SUD, current or past use pattern, and lifetime dependence) that could contribute to the association between delay discounting and the perceived risk of relapse.

- Cross-sectional mediation analysis has limitations. There is a potential for bias, and results may not reflect the same relationship seen in a longitudinal mediation analysis due to a lack of temporal precedence – that is, presumed causal variables preceding changes in subsequent theoretical mechanisms and outcomes.

- The International Quit and Recovery Registry administers monthly assessments with more than 1 assessment administering the delay discounting task leading to the possible familiarity with the task among the registry members.

- Participants were asked to self-report how long they have been in recovery from their primary substance and the number of times they relapsed. However, the definitions of recovery and/or relapse were not specified. As participants may have defined recovery and/or relapse differently when responding to the study questions, using the self-reported definition of recovery instead of standard measures to assess the recovery and relapse status is a limitation of this study.

BOTTOM LINE

This study suggests that recovering individuals who are more impulsive (i.e., have higher rates of delay discounting) may be less confident in their ability to prevent relapse. A tendency to choose the smaller immediate reward over the larger later reward could therefore be a marker for increased risk for relapse, as they may be more likely to choose substance use for its immediate rewarding effects. While greater impulsivity helped explain the association between more time in recovery and lower perceived risk for relapse, the cross-sectional nature of the study prohibits drawing conclusions about how these findings should be interpreted for people in recovery. Furthermore, delay discounting only explained about 21% of this effect indicating there are other very important factors that also explain this relationship. That said, they show delay discounting may be a marker of the recovery process, warranting future study about how delay discounting may change over time, and whether it adds to the prediction of recovery outcomes over and above known psychosocial mechanisms of behavior change like motivation, self-efficacy, and adaptive social network changes.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Continued care interventions that teach these individuals to implement future-focused thoughts and behaviors, such as cognitive training exercises, 12-step involvement, and mindfulness-based exercises might ultimately improve delay discounting, and in turn enhance relapse risk confidence and support sustained recovery. While more research is needed to determine if delay discounting is associated with actual relapse (not just perceived risk), and whether there are interventions and other activities that might help reduce delay discounting, this study provides an important foundation for better understanding the predictors of recovery confidence, and this area of research will ultimately help guide new approaches to enhance recovery for individuals and families seeking it.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study suggests that recovering individuals who are more impulsive (i.e., higher delay discounting) may feel at greater risk for relapse. Identifying more impulsive patients in recovery and implementing therapeutic approaches that encourage future-focused thoughts and behaviors – for example, to encourage patients to persevere and “hang in there” through tough times with the assurance that the later rewards of recovery will be evident and greater down the road – might help to increase hope and recovery confidence and, in turn, protect against relapse. While more research is needed to determine if delay discounting is associated with actual relapse (not just perceived risk), and whether there are interventions and other activities that might help reduce delay discounting, this study provides an important foundation for better understanding the predictors of recovery confidence, and this area of research will ultimately help guide new approaches to enhance recovery for individuals and families seeking it.

- For scientists: The authors of this study found that recovering individuals with higher rates of delay discounting may have lower confidence in their ability to stay in recovery. Additional research is needed to replicate and extend these findings. Though delay discounting is a predictor of perceived relapse risk, direct and longitudinal measurement of actual relapse in the context of this work is needed. Studies of more complex interactions can also improve understanding of the factors that moderate treatment and recovery mechanisms. Moreover, investigation is needed to determine whether cognitive remediation or clinician guided therapies that teach future-focused thoughts and behaviors (e.g., mindfulness-based exercises) can improve delay discounting, and in turn reduce risk for relapse.

- For policy makers: Studies like this help us to identify predictors of successful recovery and guide new potential continuing care approaches. With approximately 40% to 60% of individuals experiencing a lapse in recovery (return to substance use), it is essential to identify the factors contributing to it. The current study suggests that recovering individuals who are more impulsive (i.e., have higher rates of delay discounting) have lower confidence in their ability to stay in recovery. These individuals may need additional support to enhance successful recovery outcomes. Funding and policies to support continued care interventions that teach future-focused thoughts and behaviors (e.g., cognitive training exercises, 12-step involvement, mindfulness-based exercises) might improve delay discounting, and in turn enhance recovery confidence, supporting long-term recovery. Additional research is needed to replicate these outcomes and broaden our understanding of stable recovery and its predictors.

CITATIONS

Turner, J. K., Athamneh, L. N., Basso, J. C., & Bickel, W. K. (2021). The phenotype of recovery V: Does delay discounting predict the perceived risk of relapse among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(5), 1100-1108. DOI: 10.1111/acer.14600