l

Many US states have legalized cannabis for recreational use, a policy shift associated with increases in regular cannabis use and cannabis use disorder especially among young adults. Given the growing prevalence of cannabis use disorder in the population, especially among those for whom cannabis use poses the greatest neurocognitive and psychiatric risks, it might be expected that treatment admissions for cannabis-related problems have also increased, yet it’s unclear if more people are in fact seeking treatment. This study examined treatment seeking for a primary cannabis problem using a state-wide dataset of substance use disorder treatment admissions to see how cannabis-related treatment admissions have changed as a function of Proposition 64 in California, a state law legalizing recreational cannabis use and reducing criminal penalties for marijuana-related offenses.

This was an observational study that analyzed existing California state-wide public health records of 1,460,066 adults from January 2010 to December 2021 with the goal of identifying potential changes in cannabis-primary treatment admissions before and after implementation of California’s proposition 64 on November 8, 2016. A secondary goal of this study was to examine if rates of these treatment admissions were associated with an array of other variables including race, ethnicity, sex, criminal justice involvement, or Medi-Cal beneficiary status, California’s version of the federal Medicaid program.

The researchers utilized existing data from the California Outcomes Measurement System -Treatment (CalOMS-Tx), a reporting system for all publicly funded substance used disorder treatment providers in California. They coded all treatment admissions as being either for cannabis use disorder (i.e., when patients indicated cannabis was their primary substance) or primary for another substance, including alcohol and non-cannabis drugs like opioids and stimulants. It is important to note that while the study did not assess specifically for cannabis use disorder, all participants needed to meet criteria for substance use disorder to receive publicly-funded treatment in the state. Thus it is likely that those identifying cannabis as their primary substance either met criteria for cannabis use disorder and/or subjectively experienced their cannabis use as problematic. Demographic characteristics were controlled for in their models as were county-level variables like poverty and unemployment rate. Of note, before Prop 64, 42% of the sample was White, 38% Hispanic/Latino, 12% Black, and 8% another race/ethnicity. While many were referred from the criminal-legal system (35%), a majority were self-referred (38%). They were 34 years old, on average. After Prop 64, racial/ethnic demographics were similar: 43% were White, 39% Hispanic/Latino, 10% Black, and 8% another race/ethnicity. Notably, however, fewer were referred from the criminal-legal system (24%) and a higher proportion were self-referred (51%). They were 37 years old, on average.

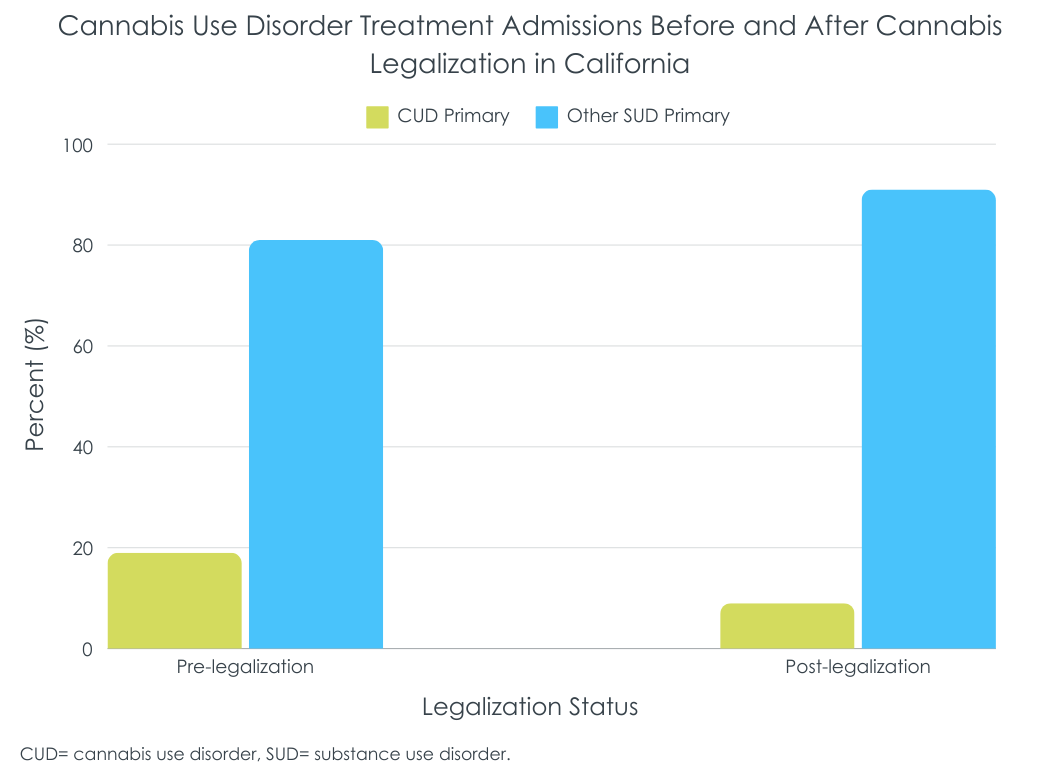

Cannabis treatment admissions decreased following Proposition 64

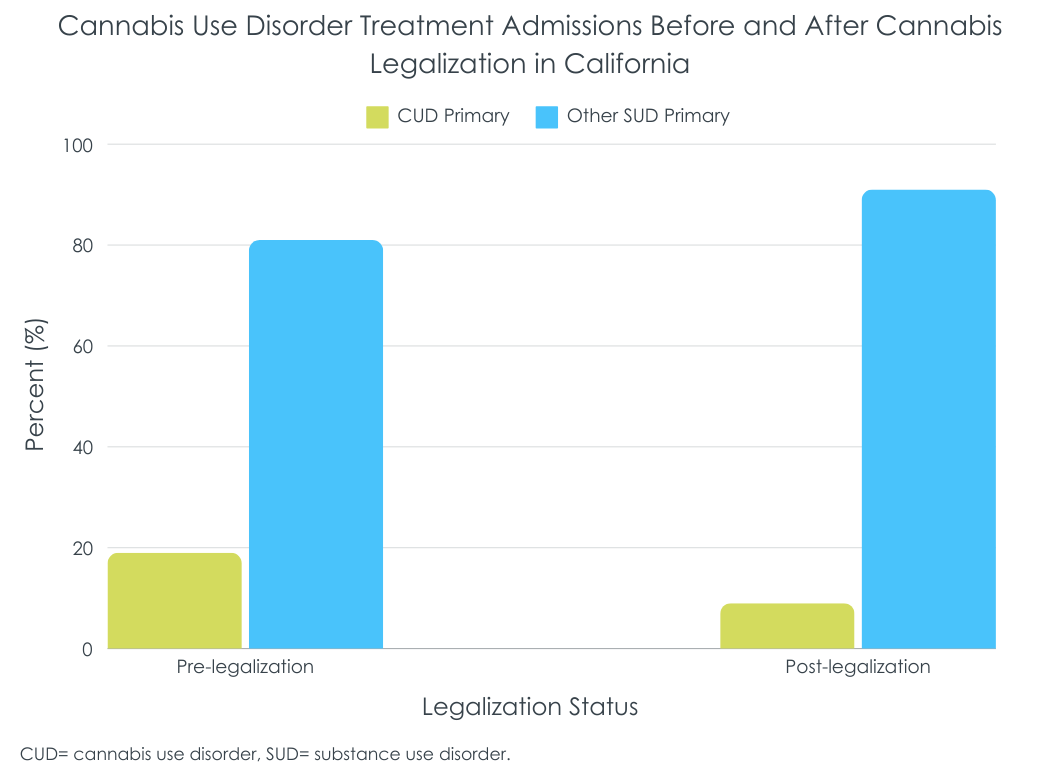

The ratio of cannabis to other drug treatment admissions reduced post-proposition 64. Pre-proposition 64, 19% of treatment admissions were cannabis-primary (i.e., 170,743 admissions), compared to 9% post-proposition 64 (i.e., 50,527 admissions). After controlling for demographic and country-level effects, this corresponded with a 5% reduction in the odds of cannabis-primary admission relative to other drugs.

The demographic make-up of people admitted also shifted

The researchers observed changes in the demographics of individuals with cannabis-primary treatment admissions relative to other drugs pre- to post-proposition 64. Males identifying cannabis as their primary substance had 24% lower odds of being admitted, while those 21 years+ (vs. young adults and teens under 21) had 12% lower odds of being admitted, indicating that larger proportions of those in cannabis treatment were female and younger (i.e., under 21). There was also a 24% reduction in the odds of Medi-Cal beneficiaries presenting for treatment, and a 21% increase in the odds of individuals being referred through the criminal justice system. In terms of the race effects, odds of admission for people identifying as White decreased 12%, while the odds of people identifying as Black and Hispanic increased 4% and 10% respectively.

After controlling for a range of individual and country-level characteristics, the number of cannabis-primary admissions decreased slightly relative to admissions where patients identified another substance like alcohol or opioids as primary in California in the years following state-level legalization of recreational cannabis use. Given recent increases in prevalence of regular cannabis use in the United States, especially among young adults, this is perhaps counterintuitive. The reason for this cannot be known from the data used in this study, though one possibility is the changing perceptions around cannabis use associated with legalization, with perceived harms and therefore perceived treatment need on the decline; in other words, there may be less pathologizing of any use or even heavy use. While notable that young adults and adolescents made up a larger share of cannabis treatment admissions after Proposition 64, at least one other study found the opposite among adolescents and young adults. Specifically, they found a dampening of the relationship between higher rates of cannabis use and treatment attendance for adolescents and young adults, speculating that the increase in the social acceptance of cannabis use attendant with legalization may be reducing the perceived need for treatment by reducing the recognition of frequent use as problematic, resulting in greater ambivalence to reduce cannabis use and/or seek help.

Another potential explanation for the study’s findings is that changes in admissions for drugs other than cannabis were also varying as a function of socio-cultural shifts over the study’s observation period (e.g., opioid-primary admissions resulting from the opioid overdose crisis). The findings reported in this paper do not account for this fact, an important point given that all analyses examined cannabis-primary admissions compared to admissions where another substance was identified as primary. It is possible that in relation to the total population of the state, cannabis-related admissions decreased more than reported here, did not markedly change, or potentially even increased pre- to post-proposition 64. It is also possible that more or less people with cannabis use disorder in California are seeking help through private treatment programs not represented in these data, or through community-based recovery support services like mutual-help programs.

Finally, another possible explanation is that fewer people whose primary substance is cannabis are being court-mandated to treatment since this drug is no longer illegal at the state level. However, the researchers’ secondary results suggest this may not be the case. After legalization, overall, when accounting for individual and county covariates, criminal-legal system referrals make up an increased share of cannabis treatment admissions in California post-legalization. Why those referred from the criminal-legal system would make up an outsized share of cannabis treatment attendees after legalizing recreational cannabis is unclear. It could be that cannabis use is correlated with illegal activities, and legalization-induced increases in cannabis use and cannabis potency may simply be leading to a larger number of participants in the legal system also using cannabis, some of whom may do so in more consequential ways.

In California, cannabis-primary treatment admissions reduced slightly relative to admissions for other substances like alcohol and opioids after legalizing recreational cannabis use in 2016. Males, Medi-Cal beneficiaries, adults, and people identifying as White were less likely to have a cannabis-primary admission relative to other drugs following legalization, while people identifying as Black, Hispanic, and with criminal justice involvement were more likely to be admitted. These findings must be interpreted with caution as rates in admissions for cannabis were compared to those for other primary drugs (e.g., opioid-primary admissions during the opioid overdose crisis), the changes in which would impact the share of cannabis admissions.

Bass, B., Padwa, H., Khurana, D., Urada, D., & Boustead, A. (2024). Adult use cannabis legalization and cannabis use disorder treatment in California, 2010-2021. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 162. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209345.

l

Many US states have legalized cannabis for recreational use, a policy shift associated with increases in regular cannabis use and cannabis use disorder especially among young adults. Given the growing prevalence of cannabis use disorder in the population, especially among those for whom cannabis use poses the greatest neurocognitive and psychiatric risks, it might be expected that treatment admissions for cannabis-related problems have also increased, yet it’s unclear if more people are in fact seeking treatment. This study examined treatment seeking for a primary cannabis problem using a state-wide dataset of substance use disorder treatment admissions to see how cannabis-related treatment admissions have changed as a function of Proposition 64 in California, a state law legalizing recreational cannabis use and reducing criminal penalties for marijuana-related offenses.

This was an observational study that analyzed existing California state-wide public health records of 1,460,066 adults from January 2010 to December 2021 with the goal of identifying potential changes in cannabis-primary treatment admissions before and after implementation of California’s proposition 64 on November 8, 2016. A secondary goal of this study was to examine if rates of these treatment admissions were associated with an array of other variables including race, ethnicity, sex, criminal justice involvement, or Medi-Cal beneficiary status, California’s version of the federal Medicaid program.

The researchers utilized existing data from the California Outcomes Measurement System -Treatment (CalOMS-Tx), a reporting system for all publicly funded substance used disorder treatment providers in California. They coded all treatment admissions as being either for cannabis use disorder (i.e., when patients indicated cannabis was their primary substance) or primary for another substance, including alcohol and non-cannabis drugs like opioids and stimulants. It is important to note that while the study did not assess specifically for cannabis use disorder, all participants needed to meet criteria for substance use disorder to receive publicly-funded treatment in the state. Thus it is likely that those identifying cannabis as their primary substance either met criteria for cannabis use disorder and/or subjectively experienced their cannabis use as problematic. Demographic characteristics were controlled for in their models as were county-level variables like poverty and unemployment rate. Of note, before Prop 64, 42% of the sample was White, 38% Hispanic/Latino, 12% Black, and 8% another race/ethnicity. While many were referred from the criminal-legal system (35%), a majority were self-referred (38%). They were 34 years old, on average. After Prop 64, racial/ethnic demographics were similar: 43% were White, 39% Hispanic/Latino, 10% Black, and 8% another race/ethnicity. Notably, however, fewer were referred from the criminal-legal system (24%) and a higher proportion were self-referred (51%). They were 37 years old, on average.

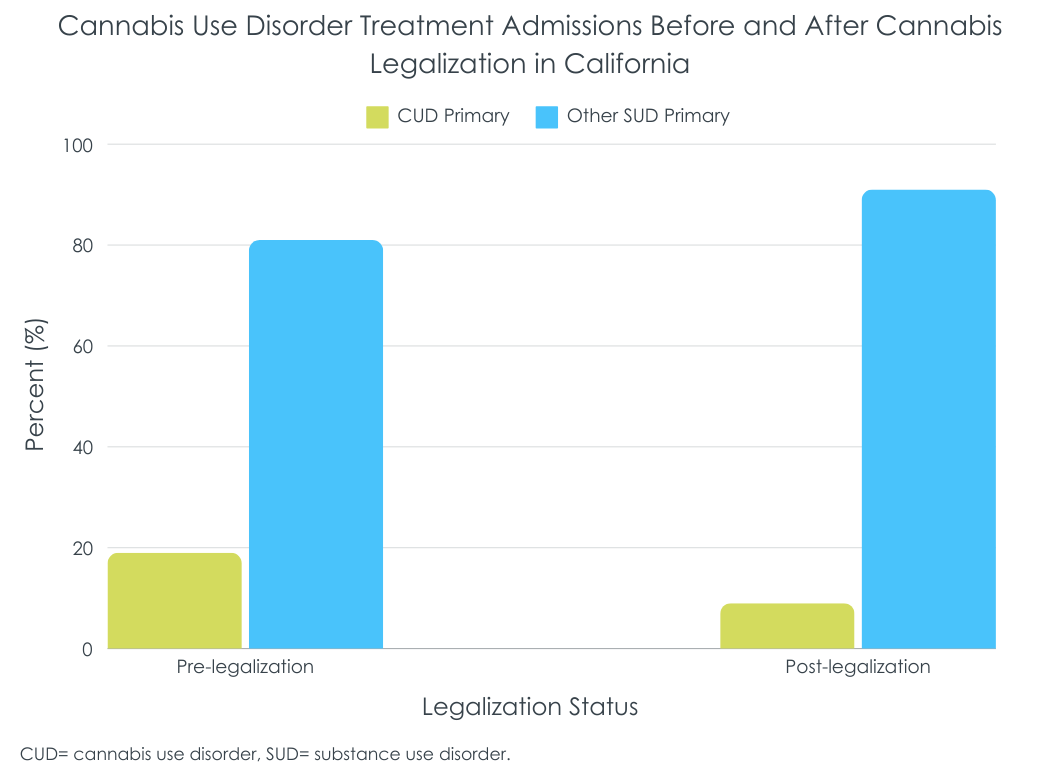

Cannabis treatment admissions decreased following Proposition 64

The ratio of cannabis to other drug treatment admissions reduced post-proposition 64. Pre-proposition 64, 19% of treatment admissions were cannabis-primary (i.e., 170,743 admissions), compared to 9% post-proposition 64 (i.e., 50,527 admissions). After controlling for demographic and country-level effects, this corresponded with a 5% reduction in the odds of cannabis-primary admission relative to other drugs.

The demographic make-up of people admitted also shifted

The researchers observed changes in the demographics of individuals with cannabis-primary treatment admissions relative to other drugs pre- to post-proposition 64. Males identifying cannabis as their primary substance had 24% lower odds of being admitted, while those 21 years+ (vs. young adults and teens under 21) had 12% lower odds of being admitted, indicating that larger proportions of those in cannabis treatment were female and younger (i.e., under 21). There was also a 24% reduction in the odds of Medi-Cal beneficiaries presenting for treatment, and a 21% increase in the odds of individuals being referred through the criminal justice system. In terms of the race effects, odds of admission for people identifying as White decreased 12%, while the odds of people identifying as Black and Hispanic increased 4% and 10% respectively.

After controlling for a range of individual and country-level characteristics, the number of cannabis-primary admissions decreased slightly relative to admissions where patients identified another substance like alcohol or opioids as primary in California in the years following state-level legalization of recreational cannabis use. Given recent increases in prevalence of regular cannabis use in the United States, especially among young adults, this is perhaps counterintuitive. The reason for this cannot be known from the data used in this study, though one possibility is the changing perceptions around cannabis use associated with legalization, with perceived harms and therefore perceived treatment need on the decline; in other words, there may be less pathologizing of any use or even heavy use. While notable that young adults and adolescents made up a larger share of cannabis treatment admissions after Proposition 64, at least one other study found the opposite among adolescents and young adults. Specifically, they found a dampening of the relationship between higher rates of cannabis use and treatment attendance for adolescents and young adults, speculating that the increase in the social acceptance of cannabis use attendant with legalization may be reducing the perceived need for treatment by reducing the recognition of frequent use as problematic, resulting in greater ambivalence to reduce cannabis use and/or seek help.

Another potential explanation for the study’s findings is that changes in admissions for drugs other than cannabis were also varying as a function of socio-cultural shifts over the study’s observation period (e.g., opioid-primary admissions resulting from the opioid overdose crisis). The findings reported in this paper do not account for this fact, an important point given that all analyses examined cannabis-primary admissions compared to admissions where another substance was identified as primary. It is possible that in relation to the total population of the state, cannabis-related admissions decreased more than reported here, did not markedly change, or potentially even increased pre- to post-proposition 64. It is also possible that more or less people with cannabis use disorder in California are seeking help through private treatment programs not represented in these data, or through community-based recovery support services like mutual-help programs.

Finally, another possible explanation is that fewer people whose primary substance is cannabis are being court-mandated to treatment since this drug is no longer illegal at the state level. However, the researchers’ secondary results suggest this may not be the case. After legalization, overall, when accounting for individual and county covariates, criminal-legal system referrals make up an increased share of cannabis treatment admissions in California post-legalization. Why those referred from the criminal-legal system would make up an outsized share of cannabis treatment attendees after legalizing recreational cannabis is unclear. It could be that cannabis use is correlated with illegal activities, and legalization-induced increases in cannabis use and cannabis potency may simply be leading to a larger number of participants in the legal system also using cannabis, some of whom may do so in more consequential ways.

In California, cannabis-primary treatment admissions reduced slightly relative to admissions for other substances like alcohol and opioids after legalizing recreational cannabis use in 2016. Males, Medi-Cal beneficiaries, adults, and people identifying as White were less likely to have a cannabis-primary admission relative to other drugs following legalization, while people identifying as Black, Hispanic, and with criminal justice involvement were more likely to be admitted. These findings must be interpreted with caution as rates in admissions for cannabis were compared to those for other primary drugs (e.g., opioid-primary admissions during the opioid overdose crisis), the changes in which would impact the share of cannabis admissions.

Bass, B., Padwa, H., Khurana, D., Urada, D., & Boustead, A. (2024). Adult use cannabis legalization and cannabis use disorder treatment in California, 2010-2021. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 162. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209345.

l

Many US states have legalized cannabis for recreational use, a policy shift associated with increases in regular cannabis use and cannabis use disorder especially among young adults. Given the growing prevalence of cannabis use disorder in the population, especially among those for whom cannabis use poses the greatest neurocognitive and psychiatric risks, it might be expected that treatment admissions for cannabis-related problems have also increased, yet it’s unclear if more people are in fact seeking treatment. This study examined treatment seeking for a primary cannabis problem using a state-wide dataset of substance use disorder treatment admissions to see how cannabis-related treatment admissions have changed as a function of Proposition 64 in California, a state law legalizing recreational cannabis use and reducing criminal penalties for marijuana-related offenses.

This was an observational study that analyzed existing California state-wide public health records of 1,460,066 adults from January 2010 to December 2021 with the goal of identifying potential changes in cannabis-primary treatment admissions before and after implementation of California’s proposition 64 on November 8, 2016. A secondary goal of this study was to examine if rates of these treatment admissions were associated with an array of other variables including race, ethnicity, sex, criminal justice involvement, or Medi-Cal beneficiary status, California’s version of the federal Medicaid program.

The researchers utilized existing data from the California Outcomes Measurement System -Treatment (CalOMS-Tx), a reporting system for all publicly funded substance used disorder treatment providers in California. They coded all treatment admissions as being either for cannabis use disorder (i.e., when patients indicated cannabis was their primary substance) or primary for another substance, including alcohol and non-cannabis drugs like opioids and stimulants. It is important to note that while the study did not assess specifically for cannabis use disorder, all participants needed to meet criteria for substance use disorder to receive publicly-funded treatment in the state. Thus it is likely that those identifying cannabis as their primary substance either met criteria for cannabis use disorder and/or subjectively experienced their cannabis use as problematic. Demographic characteristics were controlled for in their models as were county-level variables like poverty and unemployment rate. Of note, before Prop 64, 42% of the sample was White, 38% Hispanic/Latino, 12% Black, and 8% another race/ethnicity. While many were referred from the criminal-legal system (35%), a majority were self-referred (38%). They were 34 years old, on average. After Prop 64, racial/ethnic demographics were similar: 43% were White, 39% Hispanic/Latino, 10% Black, and 8% another race/ethnicity. Notably, however, fewer were referred from the criminal-legal system (24%) and a higher proportion were self-referred (51%). They were 37 years old, on average.

Cannabis treatment admissions decreased following Proposition 64

The ratio of cannabis to other drug treatment admissions reduced post-proposition 64. Pre-proposition 64, 19% of treatment admissions were cannabis-primary (i.e., 170,743 admissions), compared to 9% post-proposition 64 (i.e., 50,527 admissions). After controlling for demographic and country-level effects, this corresponded with a 5% reduction in the odds of cannabis-primary admission relative to other drugs.

The demographic make-up of people admitted also shifted

The researchers observed changes in the demographics of individuals with cannabis-primary treatment admissions relative to other drugs pre- to post-proposition 64. Males identifying cannabis as their primary substance had 24% lower odds of being admitted, while those 21 years+ (vs. young adults and teens under 21) had 12% lower odds of being admitted, indicating that larger proportions of those in cannabis treatment were female and younger (i.e., under 21). There was also a 24% reduction in the odds of Medi-Cal beneficiaries presenting for treatment, and a 21% increase in the odds of individuals being referred through the criminal justice system. In terms of the race effects, odds of admission for people identifying as White decreased 12%, while the odds of people identifying as Black and Hispanic increased 4% and 10% respectively.

After controlling for a range of individual and country-level characteristics, the number of cannabis-primary admissions decreased slightly relative to admissions where patients identified another substance like alcohol or opioids as primary in California in the years following state-level legalization of recreational cannabis use. Given recent increases in prevalence of regular cannabis use in the United States, especially among young adults, this is perhaps counterintuitive. The reason for this cannot be known from the data used in this study, though one possibility is the changing perceptions around cannabis use associated with legalization, with perceived harms and therefore perceived treatment need on the decline; in other words, there may be less pathologizing of any use or even heavy use. While notable that young adults and adolescents made up a larger share of cannabis treatment admissions after Proposition 64, at least one other study found the opposite among adolescents and young adults. Specifically, they found a dampening of the relationship between higher rates of cannabis use and treatment attendance for adolescents and young adults, speculating that the increase in the social acceptance of cannabis use attendant with legalization may be reducing the perceived need for treatment by reducing the recognition of frequent use as problematic, resulting in greater ambivalence to reduce cannabis use and/or seek help.

Another potential explanation for the study’s findings is that changes in admissions for drugs other than cannabis were also varying as a function of socio-cultural shifts over the study’s observation period (e.g., opioid-primary admissions resulting from the opioid overdose crisis). The findings reported in this paper do not account for this fact, an important point given that all analyses examined cannabis-primary admissions compared to admissions where another substance was identified as primary. It is possible that in relation to the total population of the state, cannabis-related admissions decreased more than reported here, did not markedly change, or potentially even increased pre- to post-proposition 64. It is also possible that more or less people with cannabis use disorder in California are seeking help through private treatment programs not represented in these data, or through community-based recovery support services like mutual-help programs.

Finally, another possible explanation is that fewer people whose primary substance is cannabis are being court-mandated to treatment since this drug is no longer illegal at the state level. However, the researchers’ secondary results suggest this may not be the case. After legalization, overall, when accounting for individual and county covariates, criminal-legal system referrals make up an increased share of cannabis treatment admissions in California post-legalization. Why those referred from the criminal-legal system would make up an outsized share of cannabis treatment attendees after legalizing recreational cannabis is unclear. It could be that cannabis use is correlated with illegal activities, and legalization-induced increases in cannabis use and cannabis potency may simply be leading to a larger number of participants in the legal system also using cannabis, some of whom may do so in more consequential ways.

In California, cannabis-primary treatment admissions reduced slightly relative to admissions for other substances like alcohol and opioids after legalizing recreational cannabis use in 2016. Males, Medi-Cal beneficiaries, adults, and people identifying as White were less likely to have a cannabis-primary admission relative to other drugs following legalization, while people identifying as Black, Hispanic, and with criminal justice involvement were more likely to be admitted. These findings must be interpreted with caution as rates in admissions for cannabis were compared to those for other primary drugs (e.g., opioid-primary admissions during the opioid overdose crisis), the changes in which would impact the share of cannabis admissions.

Bass, B., Padwa, H., Khurana, D., Urada, D., & Boustead, A. (2024). Adult use cannabis legalization and cannabis use disorder treatment in California, 2010-2021. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 162. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209345.