Does combining cannabis with opioids for chronic pain management leave people better or worse off?

Many promote cannabis as a safe and effective drug for chronic pain management, and have gone as far to argue that cannabis can reduce the need for opioid pain medications. At the same time, it is well appreciated that the co–use of certain substances is generally associated with poorer outcomes than single substance use. In this study, authors found that individuals with chronic pain who combine opioids and cannabis are not functioning as well as those who are only using opioids. Although the exact nature of this relationship is unclear, the results may have implications for medical cannabis in the context of chronic pain management.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Many people argue that cannabis is a safe and effective drug for chronic pain management, and have gone as far to say that cannabis can reduce the need for opioid pain medications and the risks that go with this class of drug. At the same time, the co-use of certain substances is generally associated with poorer outcomes than single substance use. In this article, Rogers and colleagues assessed whether individuals who were combining cannabis with opioids to manage chronic pain had less self-reported pain than those using opioids alone, and whether individuals combining cannabis and opioids had more mood–related problems. The authors also explored whether these individuals are more or less likely to have problems with opioids and engage in the use of other substances.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This cross-sectional study surveyed 450 United States adults who endorsed taking opioids to manage chronic pain. Of these 450 people, 176 endorsed also using cannabis for pain management. Participants were asked about their opioid and cannabis use, as well as any use of other substances, including nicotine. Participants were also assessed for opioid use problems, as well as anxiety and depression. Questionnaires administered included 1) the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST), an 8-item questionnaire designed to asses risk of substance use involvement, 2) the patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), a 4-item self-report measure comprised of the PHQ-2 for depression and the GAD-2 for anxiety, 3) the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) that is used to identify individuals who are exhibiting behaviors of problematic opioid use, 4) the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS), a measure severity of dependence to opioids, and 5) the Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS), a measure that assesses pain intensity and pain disability. The authors statistically controlled for differences among study participants in age, sex, income, and education.

Participants were adults ages of 18 to 64 (74.67% female, average 38.59 years old, standard deviation of 11.09) reporting current opioid use for pain and current chronic pain that persisted for at least 3 months. The sample was predominately White (77.8%), with another 8.7% identifying as Black/African American, 13.1% Hispanic/Latino, 3.3% Native American/Alaska Native, 0.9% Asian/Pacific Islander 2.7% multiracial, and 1.1% other. In terms of education, a little over a fifth (5.8%) did not complete high school, whereas over a quarter of the sample (31.3%) reported attaining a high school diploma, with 22.4% reporting ‘‘some college,’’ and 40.4% having attained an associate’s degree or higher.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

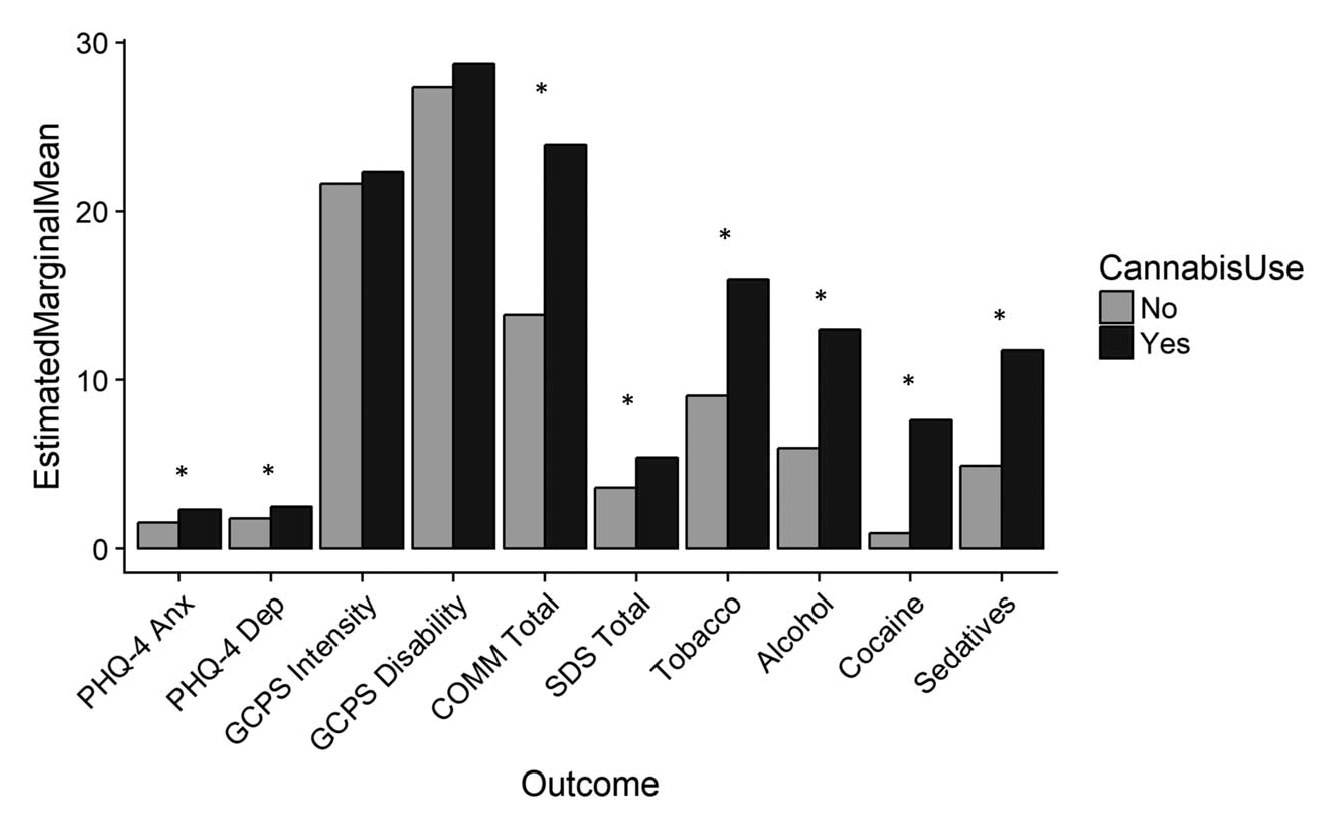

Compared to participants using opioids alone to manage chronic pain, those combining opioids with cannabis endorsed greater anxiety and depression. Notably, participants combining opioids and cannabis were also more likely to be taking opioids not as prescribed and had greater scores on an opioid dependence severity scale, and were more likely to be using tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, and sedatives. This overall pattern of poorer functioning and risky substance use is illustrated in the figure below. At the same time, participants combining opioids and cannabis reported pain levels similar to those using opioids alone.

Figure 1. Graph showing differences between study participants using opioids alone (grey bars), and opioids in conjunction with cannabis (black bars) to manage chronic pain. Measures are reported as estimated marginal means (vertical axis); in other words, the mean response for each measure, adjusted for the other reported measures. The asterisk (*) indicates a highly significant difference at the p< 0.005 level, meaning the differences observed are highly unlikely to be due to chance. It is important to note that the range of possible scores on each measure is different. Participants combining opioids and cannabis reported more anxiety and depression, were more likely to be using opioids not as prescribed and endorse more symptoms associated with opioid dependence, and were more likely to be using tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, and sedatives. PHQ-4 Anx= Anxiety, PHQ-4 Dep= Depression, GCPS Intensity= Pain intensity, GCPS Disability= Pain disability, COMM Total= Current not as prescribed opioid use, SDS Total= Severity of opioid dependence (Source: Rogers et al., 2018).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This paper’s findings suggest that combining opioids with cannabis to manage chronic pain doesn’t help with pain over and above taking opioids alone, although it is possible that those combining opioids with cannabis had greater pain to begin with that was not being adequately managed with opioids alone. At the same time, it should be noted that participant pain scores, on average, were not especially high. Both groups reported pain intensity and pain-related disability scores on the Graded Chronic Pain Scale that were in the low range. It is possible this sample represents individuals with less severe chronic pain. As such, it is possible these results would not generalize to adults with more severe pain intensity and disability.

Problematically, those combining opioids with cannabis had greater anxiety and depression than those using opioids alone, although the absolute differences between groups on these measures was not large. Because this is a cross sectional study (i.e., a single survey providing a snapshot in time), it is impossible to know whether cannabis use was leading to greater anxiety and depression, or individuals with greater anxiety and depression were more likely to be using cannabis to cope. If these more vulnerable individuals are, in fact, using cannabis to cope with difficult mental health concerns, it does not seem to be helping subjectively given their poorer functioning, although it could be that they had higher anxiety and depression to begin with, and cannabis use brought this down to the same level.

Those combining opioids with cannabis were also more likely to be taking opioids not as prescribed and have symptoms of opioid dependence, in addition to endorsing using other substances. It is possible these individuals may represent a subset of people with chronic pain and greater overall substance use-related problems.

Also, these individuals were possibly purchasing cannabis from the illicit market in which strains with higher THC contents predominate (the compound in cannabis that causes euphoria/high). This study cannot tease apart whether CBD (a compound in cannabis thought to have some therapeutic benefits but does not cause euphoria/high) in combination with opioids for chronic pain would be associated with different mental health and substance use outcomes.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As the authors note, because this was a cross-sectional study (i.e., a single survey providing a snapshot in time), it is impossible to know if differences between groups were causes or effects of cannabis use in addition to opioid use.

- It is not clear whether opioids or cannabis were prescribed, or the kinds of quantities participants were taking.

- The authors also highlight the fact that geographic location was not controlled for in this study. It is therefore not clear how participants’ location influenced results. For instance, it is not known if individuals using cannabis lived in areas where cannabis is legal.

- Also, all data in this paper were provided by self-report. Because participants were not objectively tested for substance use (i.e., with laboratory tests), it cannot be known if participants underreported or overreported substance use.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Results suggest that using cannabis in addition to opioids may not have an additive benefit on pain reduction for individuals with chronic pain. Also, it appears those combining opioids and cannabis may be more likely to experience problems with opioids. Though it cannot be determined if cannabis in addition to opioids for chronic pain leads to greater substance use problems, or people with greater opioid use problems are simply more likely to use cannabis, it is recommended that those taking opioids for chronic pain conditions reduce their risk for developing substance use problems by not combining drugs.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: At least for people experiencing mild pain, present findings suggest there may not be a benefit for cannabis use over and above opioid use and indicate that combining these substances is associated with greater substance use problems, and higher levels of negative affect. It is not clear, however, whether there would be benefit for individuals with greater pain severity.

- For scientists: Results suggest that using cannabis in addition to opioids may not have an additive benefit on pain reduction for individuals with chronic pain and that combining these drugs may be associated with greater drug-related problems. Considering the growing legalization of cannabis around the United States and other countries around the world, more work is urgently needed to better understand the possible public health implications of this drug combination.

- For policy makers: Results suggest that using cannabis in addition to opioids may not have an additive benefit on pain reduction for individuals with chronic pain and that combining these drugs may be associated with greater drug-related problems. The findings in this paper are preliminary, but they speak to risks associated with combining cannabis with opioids. Funding research in this area is critical considering the growing legalization of cannabis around the United States and other countries around the world. Cannabis legalization, and with it easier, cheaper access to this drug will likely result in more individuals combining opioids with cannabis to manage chronic pain. Based on the findings reported by these authors, the negative public health implications of this could be great, but more longitudinal research is necessary to help understand whether in fact various cannabis components (e.g., THC, CBD) have therapeutic potential for low-moderate pain either alone or in combination with opioids.

CITATIONS

Rogers, A. H., Bakhshaie, J., Buckner, J. D., Orr, M. F., Paulus, D. J., Ditre, J. W., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2018). Opioid and cannabis co-use among adults with chronic pain: Relations to substance misuse, mental health, and pain experience. Journal of Addiction Medicine, (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000493