Can certain alcohol use disorder medications help reduce risk for hospitalizations and death?

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized as a treatment option for alcohol use disorder though research shows certain medications may improve alcohol outcomes. Research on pharmacotherapy health outcomes beyond alcohol consumption in real-world settings can provide important knowledge on their overall clinical and public health utilities. This study of 125,556 Swedish residents diagnosed with alcohol use disorder examined the long-term effectiveness of alcohol use disorder medication and found that certain medications were associated with decreased risk for hospitalizations.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Alcohol use disorder is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for approximately 5% of the world’s disease burden (i.e., premature death and disability) and contributing to over an estimated 200 diseases and injury-related health conditions such as cirrhosis and cancer. Psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorder—such as cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational enhancement therapy, and 12-step facilitation (clinical linkage to community-based groups like Alcoholics Anonymous [AA]) – are empirically-supported first-line interventions. Pharmacotherapies are also used to treat alcohol use disorder, though they are used far less frequently than psychosocial treatments, despite evidence supporting their efficacy for reducing binge drinking and helping patients maintain abstinence, among other benefits.

The medications acamprosate (known by the brand name Campral), naltrexone (prescribed either as a daily oral medication or as a monthly injection known by the brand name Vivitrol), and disulfiram (known by the brand name Antabuse) are currently approved in the United States by the FDA and in Europe to treat alcohol use disorder. The medication nalmefene is also approved for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in Europe, but not in the United States. Although research indicates that these medications can improve outcomes among individuals with alcohol use disorder, estimates suggest that these medications are prescribed to less than 9% of individuals with alcohol use disorder who may benefit from them.

Much of the research on pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder has occurred in controlled clinical settings. Little is known, however, about the effects of pharmacotherapies in real-world settings, particularly on long-term health and work-related outcomes. Research on real-world health outcomes could help increase knowledge of the benefits of medications for alcohol use disorder, and in turn, increase their utilization among individuals with alcohol use disorder. The current study seeks to address this evidence gap by examining the real-world effectiveness of four different medications used for treating alcohol use disorder (disulfiram, acamprosate, naltrexone and nalmefene) by examining risk for hospitalizations, disability, and death in a nation-wide cohort study of approximately 125,000 patients.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a prospective population-based cohort study that included 125,556 Swedish residents who had first-time treatment contact for alcohol use disorder between July 2006 and December 2016. Participants were followed up either until death, diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, emigration, or study end (whichever came first), to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of four pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorder (disulfiram, acamprosate, naltrexone and nalmefene) by examining risk for hospitalizations, disability, and death.

Participants were Swedish residents who were between the ages of 16 and 64 years at the time of their alcohol use disorder diagnosis. The research team used four nation-wide Swedish register sources to identify participants: inpatient care (via the National Patient Register), specialized outpatient care (via the National Patient Register), disability pension (via the Microdata for analyses of social insurance (MiDAS) register), and sickness absence data (via the MiDAS register).

This study also used data from the country’s Prescribed Drug Register to determine which participants had used medication for alcohol use disorder, and then categorized their use of disulfiram, acamprosate, naltrexone and nalmefene as either a single alcohol use disorder medication used by itself (i.e., monotherapy) or two or more alcohol use disorder medications used together at the same time (i.e., polytherapy), looking specifically at the use of disulfiram and acamprosate, disulfiram and naltrexone, and naltrexone and acamprosate as polytherapies. The research team then evaluated the effectiveness of the medications as both monotherapies and polytherapies. The research team also looked at benzodiazepine use because it is frequently misused among individuals with AUD. Although benzodiazepines can be used to help manage alcohol withdrawal, they are not FDA approved medications for alcohol use disorder.

The primary outcome in this study was hospitalization due to alcohol use disorder, which was defined as an inpatient stay of at least 24 hours and determined using the National Patient Register. The secondary outcomes were hospitalization due to any cause, hospitalization due to alcohol-related somatic causes (i.e., alcoholic liver disease, alcohol-induced pancreatitis, Wernicke’s encephalopathy, etc.), work disability (i.e., disability pension or absence due to sickness), and mortality.

To analyze the data, researchers used a “within individual” design whereby each participant acted as their own control – i.e., time periods taking alcohol use disorder medication were compared to time periods not taking alcohol use disorder medication. Each time a participant experienced an outcome event, such as a hospitalization or work disability, the follow-up timepoint would “reset” to zero and start again, until the participant experienced another outcome event (e.g., another hospitalization), at which point the follow-up timepoint would reset again. This means that researchers compared recurrent outcomes, such as hospitalizations, within each individual.

Participants in this sample were 38.1 years old, on average, about two-thirds male (62.5%), just over half were single without children (52.7%), and most were born in Sweden (86.3%). The median follow-up time period was 4.6 years. 6.2% of study participants (n = 7,832) died during the follow-up period.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Approximately 25.6% of the sample used one or more medications for alcohol use disorder and disulfiram was the most commonly used medication.

One-quarter, or 25.6% (n = 32,129), of the 125,556 participants in this study used one or more medications for alcohol use disorder. Of the 125,556 study participants,15.4% used disulfiram, 9.1% used acamprosate, 8.7% used naltrexone, 0.6% used nalmefene, and 5.1% used two or more drugs concomitantly.

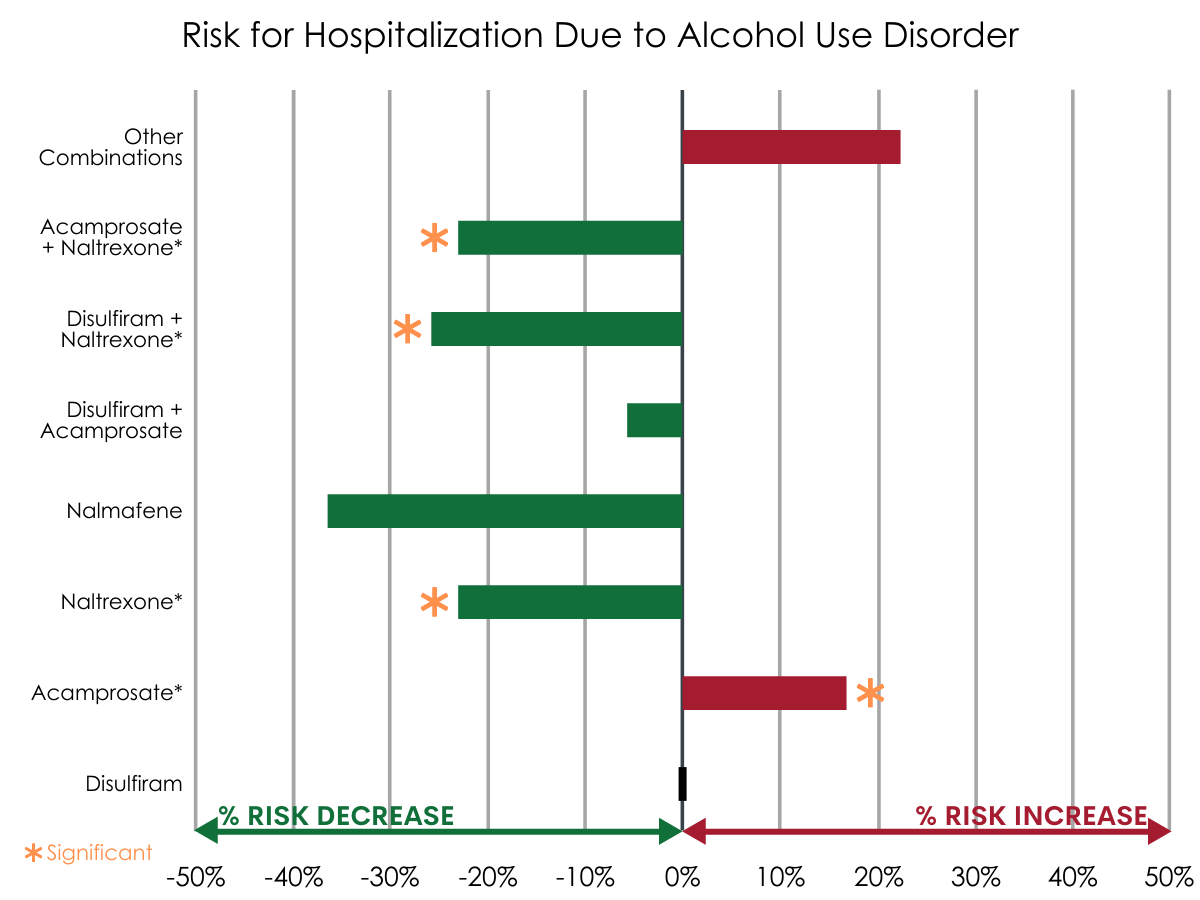

Naltrexone as a monotherapy and naltrexone combined with either disulfiram or acamprosate were associated with a reduced risk of hospitalization due to alcohol use disorder.

Nearly one-quarter (23.9%) of participants (n = 30,044) in this study had at least one main outcome event, meaning that they were hospitalized because of their alcohol use disorder some time during the study period.

Participants who used 1) naltrexone as a monotherapy, 2) naltrexone combined with disulfiram, or 3) naltrexone combined with acamprosate, had a lower risk of hospitalization due to alcohol use disorder when compared to times when the same individuals were not taking any alcohol use disorder medication. Conversely, the use of acamprosate as a monotherapy was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization due to alcohol use disorder.

Figure 1.

Polytherapy (any combination) and disulfiram were associated with a reduced risk of hospitalization due to alcohol-related somatic causes.

A small proportion of participants (2.5%; n = 3,173) were hospitalized due to alcohol-related somatic causes (e.g., alcoholic liver disease, alcohol-induced pancreatitis) during the study period. Polytherapy (of any combination) and disulfiram monotherapy was associated with a significantly decreased risk of hospitalization due to alcohol-related somatic causes. Here, “polytherapy” consisted of any combination of the 4 study drugs due to a low rate of occurrence among individuals hospitalized due to alcohol-related somatic causes. Nalmefene monotherapy was not included in this analysis due to its low rate of use among this group.

Benzodiazepines were associated with an increased risk of mortality and hospitalization due to alcohol use disorder.

Approximately one-third (34%) of study participants (n = 42,678) used benzodiazepines during the follow-up period. Benzodiazepine use was not associated with an increased risk of hospitalization due to somatic causes but was associated with an increased risk for hospitalization due to alcohol use disorder. Additionally, the adjusted risk of all-cause mortality was higher for participants who used benzodiazepines. None of the four alcohol use disorder medications were associated with an increased or decreased risk of mortality.

The risk of work disability did not decrease due to the use of any of the four studied alcohol use disorder medications.

Less than 5% (4.2%; n = 4,719) of participants had a sickness absence or disability pension (i.e., work disability) during the study follow-up period. The risk of work disability did not decrease due to use of any of the four alcohol use disorder medications.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The research team found that certain medications, when used as either monotherapies (i.e., naltrexone, disulfiram) or polytherapies, were associated with a reduced risk for alcohol use disorder hospitalizations among participants. Specifically, naltrexone as a monotherapy or as a polytherapy when combined with disulfiram or acamprosate, were found to reduce risk for alcohol use disorder hospitalizations. Naltrexone is reportedly the most studied medication that is FDA-approved for treating alcohol use disorder and there is strong clinical evidence to support its use. It has been found to reduce alcohol craving and relapse, which could help explain why individuals who used this medication had a lower risk for alcohol use disorder hospitalization. The efficacy of naltrexone when combined with other alcohol use disorder medications is less understood. It could be that combining alcohol use disorder medications that act on different systems increase their efficacy, or that individuals who are willing to take more medications, each with the potential for side effects, may be more committed to their treatment, or some combination of the two. However, there is also research that has found no additional benefits in drinking outcomes when alcohol use disorder medications, such as naltrexone and acamprosate, are combined. Thus, additional research is needed to better understand the efficacy of alcohol use disorder medication combinations used as polytherapies.

Additionally, the use of disulfiram as a monotherapy was associated with a decreased risk of hospitalization due to alcohol-related somatic causes. Disulfiram works by interfering with the metabolism of alcohol, thereby producing an aversive reaction when an individual consumes alcohol that can include nausea and vomiting, headache, and heart palpitations, among other reactions. Thus, the effect with this medication is indirect as the daily dosing (ideally with monitoring and support from a significant other) helps the patient stay mindful of the highly unpleasant consequences of drinking while taking the medication helping to prevent impulsive use. Many of the alcohol-related somatic diagnoses in this study, such as alcoholic liver disease, alcohol-induced pancreatitis, and Wernicke’s encephalopathy, are associated with long-term alcohol use. The considerable aversive effects one experiences when consuming alcohol while taking disulfiram encourages abstinence from alcohol which, in turn, would reduce the chances of any alcohol use. This could account, in part, for the finding that disulfiram is associated with a decreased risk of hospitalization due to somatic causes.

The use of acamprosate was associated with an increased risk in alcohol use disorder hospitalizations in this study. Unlike naltrexone and disulfiram, acamprosate is not metabolized by the liver and may be an option for individuals with alcohol use disorder with liver disease who are not able to take naltrexone or disulfiram. It is therefore possible that the individuals in this study who used acamprosate as a monotherapy were patients with more severe or more chronic (or both) alcohol use disorder. This suggests that the association between acamprosate and increased risk for alcohol use disorder hospitalizations could instead reflect a relationship between alcohol use disorder severity/chronicity and risk for alcohol use disorder hospitalization. However, more research would be needed to test this possibility.

There were no associations between the use of nalmefene and risk of hospitalization due to alcohol use disorder, work disability, or mortality. Notably, this was the most infrequently used medication, with only 0.6% of participants (n = 693) in the study using nalmefene at any time during the follow-up period. Its particularly low rate of use among individuals in this study may have contributed to these findings.

Overall, approximately one in four (25.6%) participants in this study used medication for alcohol use disorder. The strongest evidence emerged in favor of naltrexone, though it was the third most commonly used medication among individuals in this study (8.7% of sample), following disulfiram (15.4% of sample) and acamprosate (9.1% of sample). Given the nature of the study design however, it cannot be said that naltrexone is “the best” at keeping people out of the hospital as it could be that those prescribed that particularly medication may have been less severe (compared to disulfiram, for example).

Of particular concern was that approximately one in three (34%) participants in this sample used benzodiazepines, and that benzodiazepine use was found to be associated with an increased risk of mortality and hospitalization due to alcohol use disorder. Notably, because this study used prescription purchase records to determine medication use, this means that these participants were all prescribed benzodiazepines. Thus, while alcohol use disorder medications as a whole appear to be underutilized in this clinical population, there appears to be a problematic overutilization—and potentially, over prescription—of benzodiazepines. Indeed, benzodiazepine use may potentiate the risks of alcohol consumption – e.g., during recurrence of use – as they are both central nervous system depressants. Because of its association with increased mortality for individuals with alcohol use disorder, this study highlights the marked risks of benzodiazepines for those with alcohol use disorder outside of its short-term use for managing alcohol withdrawal in clinically controlled environments.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The observational nature of the study design cannot speak to the relative efficacy of each medication as there are multiple reasons why someone may or may not be prescribed or taking any or a specific type of AUD medication.

- The data from this study do not indicate when participants started taking medication in relation to their alcohol use disorder diagnosis. From an efficacy standpoint, there may be certain times that are more optimal than others to begin taking these medications, which could have an impact on the outcomes reported in this study. Similarly, the data don’t take alcohol use disorder severity into account, which is another important factor that will impact the study outcomes and medication efficacy.

- The data from this study do not indicate whether or not participants used psychosocial treatments for alcohol use disorder and if so, what kinds of treatments, how frequently, and for how long. These factors are also likely to have an important impact on the outcomes evaluated in this study.

BOTTOM LINE

The researchers in this study found that naltrexone as a monotherapy, and as a polytherapy in combination with either acamprosate or disulfiram, was associated with a decreased risk of alcohol use disorder hospitalization. Disulfiram monotherapy was associated with a decreased risk in hospitalizations due to alcohol-related somatic causes.

Approximately one in four participants in this study used one or more medications for alcohol use disorder. Benzodiazepines, which are not approved to treat alcohol use disorder but are often used to manage the effects of alcohol withdrawal, were prescribed to approximately one-third of participants and associated with an increased risk of mortality. Thus, there appears to be an underutilization of alcohol use disorder medications that have demonstrated positive effects on alcohol use disorder-related outcomes and a problematic overutilization of benzodiazepines that are associated with negative alcohol use disorder-related outcomes.

Nonetheless, the findings from this study build on research showing naltrexone, acamprosate and disulfiram improve drinking outcomes. Importantly, these findings occurred outside of a clinically controlled environment in a real-world setting within a particularly large sample, which is a strength of this study.

While researchers have not yet found ways to combine medication and psychosocial treatment that outperform either one alone, future work on combining pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder with specific types of alcohol use disorder treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, or 12-step facilitation, could help determine for whom pharmacotherapy works best and how to potentially bolster its effects. Another promising line of alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy research involves personalized medicine, with previous work showing individuals who drink for its rewarding and pleasurable effects (i.e., “reward” drinkers) may benefit more from naltrexone.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Patients with alcohol use disorder and their families may wish to learn about the various pharmacotherapies available to treat alcohol use disorder, along with their potential benefits and risks. They may also wish to ask their treatment providers about how pharmacotherapies may be used in combination with alcohol use disorder talk therapies, to better understand the breadth of treatment options available to them.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Treatment providers who work with individuals with alcohol use disorder are encouraged to discuss pharmacotherapy as one of the available options for treating alcohol use disorder. However, given that there appears to be an increased risk for mortality among individuals with alcohol use disorder who use benzodiazepines (for purposes other than managing alcohol withdrawal), providers are encouraged to educate their patient and other providers about the risk for benzodiazepine misuse in combination with alcohol and associated increased risk of mortality.

- For scientists: Additional research is needed to further investigate how alcohol use disorder severity, initiation of medication use in relation to alcohol use disorder diagnosis or a new recovery attempt, length of medication use, comorbid conditions, and use of psychosocial treatments affect the effectiveness of alcohol use disorder medications. Research focused on identifying for whom alcohol use disorder medication works best and the optimal point in treatment to initiate use could help expand its utility and the breadth of treatment options available to individuals with alcohol use disorder. Furthermore, it is unclear how the concomitant use of benzodiazepines and alcohol use disorder medications may affect alcohol use and related outcomes. More research is needed to disentangle theses effects.

- For policy makers: Though largely underutilized, medications for alcohol use disorder can benefit individuals struggling with harmful alcohol use. Ensuring that alcohol use disorder medications are available, accessible, and covered by insurance could help expand treatment access and improve outcomes for these individuals, as well lead to cost savings by decreasing risk for hospitalizations.

CITATIONS

Heikkinen, M., Taipale, H., Tanskanen, A., Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., Lähteenvuo, M., & Tiihonen, J. (2021). Real-world effectiveness of pharmacological treatments of alcohol use disorders in a Swedish nation-wide cohort of 125 556 patients. Addiction, [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1111/add.15384