l

College students consume alcohol and other drugs at higher rates than the general population, with rates increasing in the past two decades. Though many decrease their use after leaving the college environment – which reinforces higher rates of use through social norms – some persist in these higher levels. With ongoing consequences that interfere with the achievement of important developmental milestones, including academics and employment. Also, those with more substance use during young adulthood (sometimes called “emerging adulthood”) are at greater risk for substance use disorder later in life, highlighting the importance of intervention during this life stage.

Many empirically-supported interventions exist, including cognitive-behavioral therapies, mutual- help groups, and brief interventions. Yet, most students report low motivation to reduce their substance use or to engage with these services. This lower motivation persists despite proliferation of these services’ availability, in addition to a growing national “sober curious” movement. It is possible that in comparison to non-college students with substance use disorder, those in college, on average, are less severe – e.g., experiencing some consequences, but not as many as typically older individuals not in college. Nationally, only a subset of people with substance use disorder receive treatment, with only 13% receiving any form of assistance. There are no estimates of treatment seeking, however, in college students. This study examined updated, nationally representative prevalence rates of substance use disorder and treatment seeking, as well as factors associated with a greater likelihood of attending treatment or mutual-help groups among college students.

This was a cross-sectional analysis of publicly available data from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Curated by the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the survey is administered annually to track trends in prevalence of substance use, mental health, and treatment seeking among American civilians 12 years of age or older.

The current analyses used data from 6,115 people over the age of 16 who reported being currently enrolled in a college or university. The study also examined differences between college students with substance use disorders and 9,138 non-students with substance use disorders. Notably, the comparison sample included non-students of all ages. The researchers were primarily interested in understanding prevalence of substance use disorder, in addition to rates of treatment and mutual-help attendance, among college students.

College students responded to questions about past-year substance use, including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, hallucinogens, and inhalants. If participants endorsed use of a substance, they answered questions assessing diagnostic criteria for that substance use disorder (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Psychiatric Disorders – fifth edition). The researchers classified college students as having a past-year substance use disorder if they met criteria for an alcohol or other drug use disorder (at least two or more symptoms) and/or if they received treatment for substance use in the past year in any setting. This includes in a hospital, an inpatient or outpatient facility, a mental health center, an emergency room, a doctor’s office, a prison/jail, a mutual-help group, or in any virtual format. Treatment setting was categorized as specialty, physical/mental healthcare, mutual-help group, criminal legal system, virtual/telehealth, or any setting, each coded dichotomously as non-mutually exclusive categories, as individuals may have received treatment via multiple settings and modalities. Participants who indicated that they had received treatment for alcohol or other drug use in any setting in the past year were considered to have received “treatment”.

The researchers also examined individuals factors that were associated with being more or less likely to have attended treatment including psychological stress, biological sex (male, female), age (16–20, 21–25, 26+), type of current educational program (graduate, undergraduate), enrollment status (full-time, part- time), insurance (private or combination of public and private, public-only, uninsured), self-identified race or ethnicity (coded as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic multiracial, and Hispanic), and sexual orientation (coded dichotomously as heterosexual or gay/lesbian/bisexual) and use of 2+ substances (i.e., polysubstance use).

The researchers first examined prevalence rates of substance use disorders and differences in key predictor variables between college students with and without substance use disorders. Next, the researchers examined differences in predictor variables between non-student and students with substance use disorders. While the study did not include demographic characteristics of this non-student comparison group, it was weighted like the college student sample. This process maximizes the chances that any observed differences between students and non-students are due to their student status and not some other variable (e.g., where younger individuals typically have fewer substance use disorder symptoms, on average).

Prevalence and predictors of substance use disorder among college students

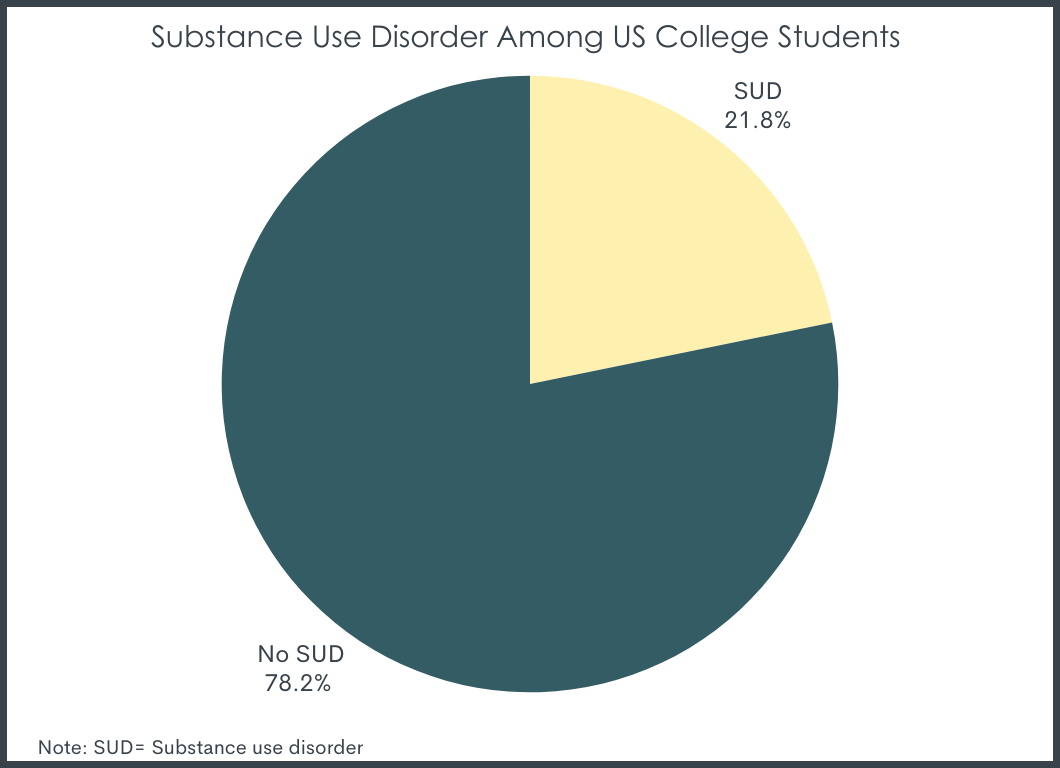

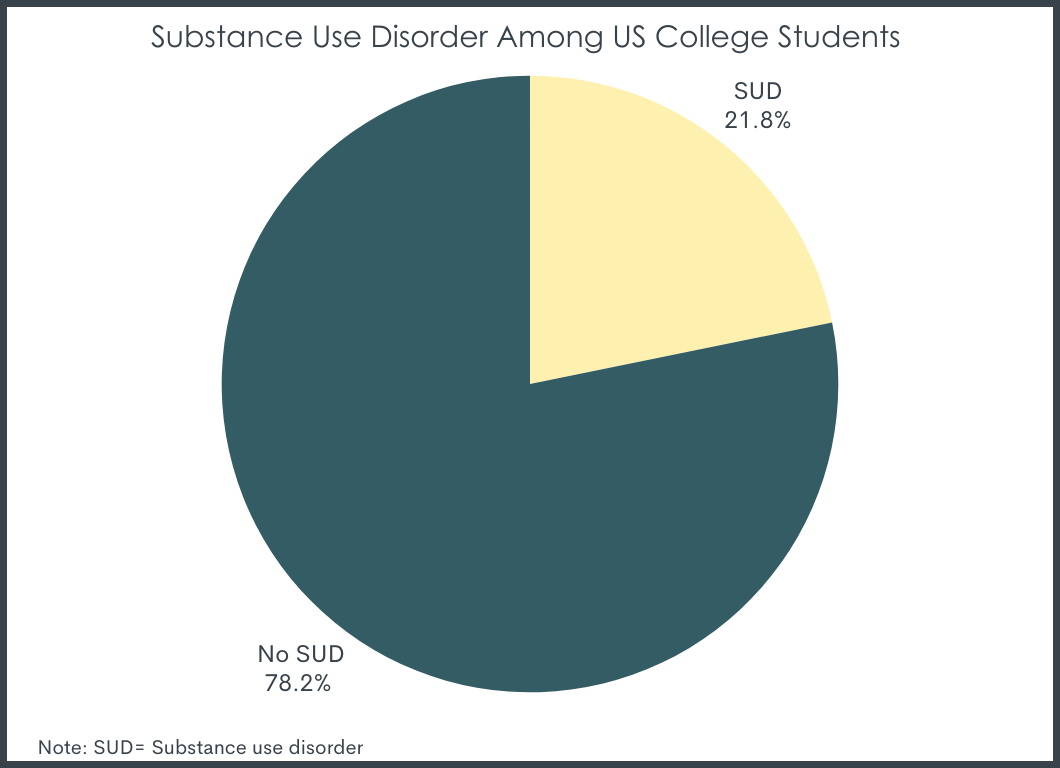

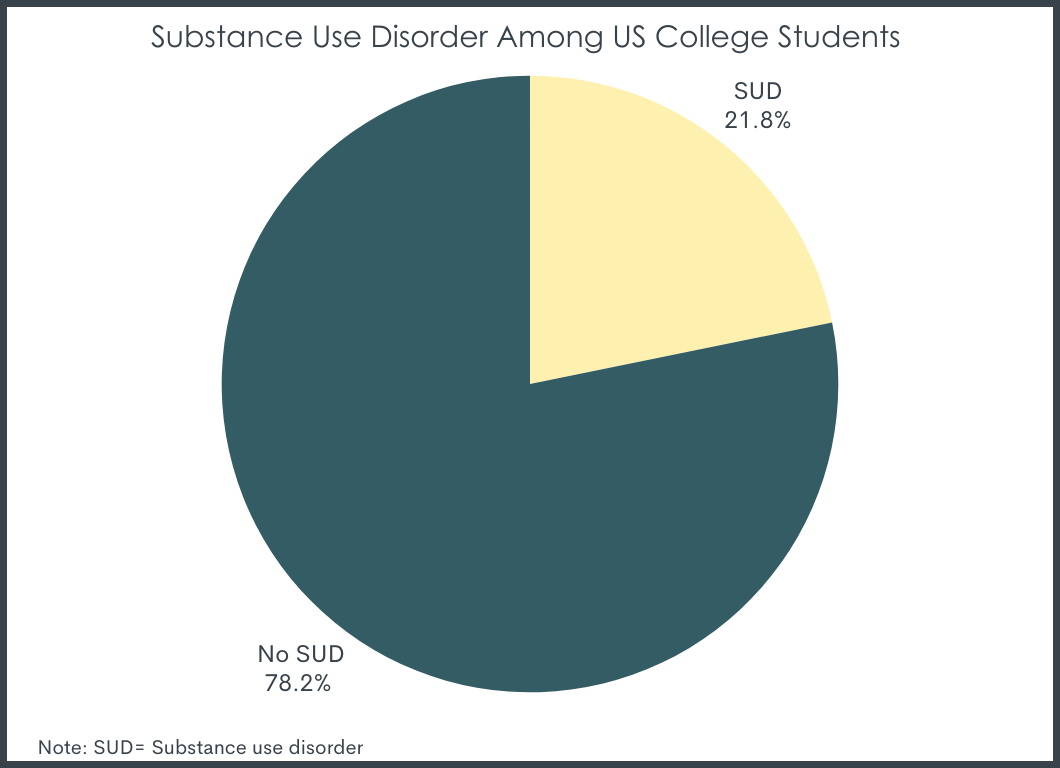

One in every 5 college students met criteria for a substance use disorder (21.8%). Compared to college students without a substance use disorder, college students who met substance use disorder criteria were older (21-25 compared to 16-20), male, and had more psychological distress. As would be expected, substance use in the past year (e.g., of alcohol, cannabis, opioids, stimulants, etc.) was associated with increased risk of meeting past-year substance use disorder criteria as well.

Students vs non-student peers with substance use disorder

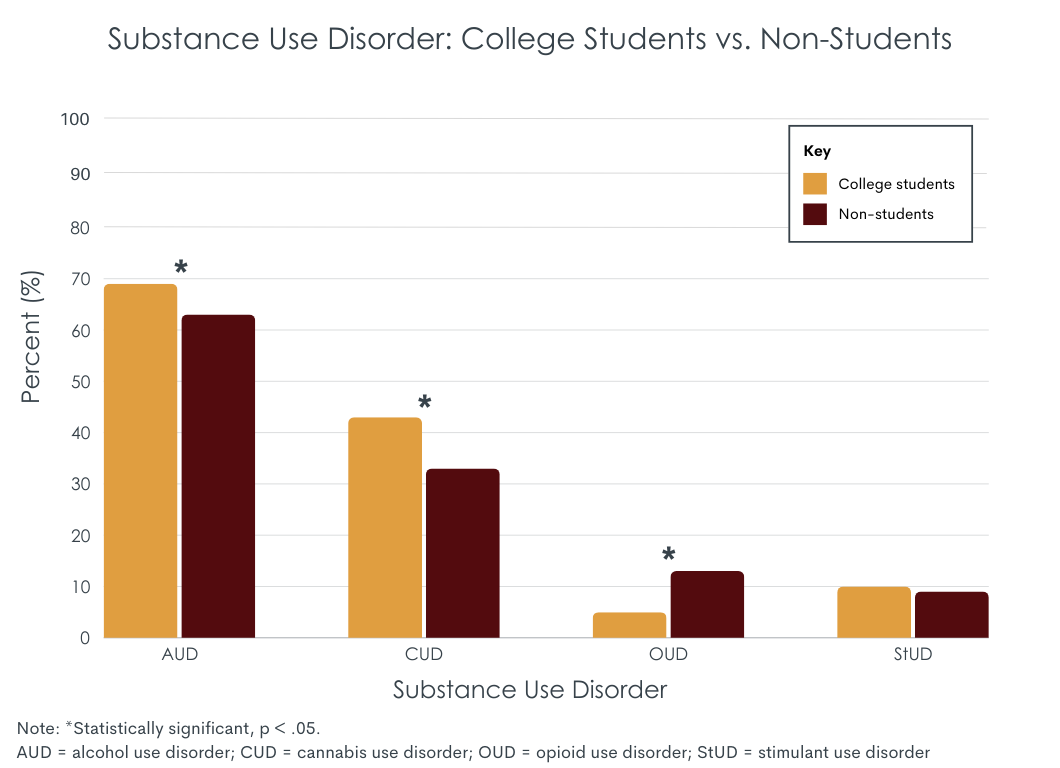

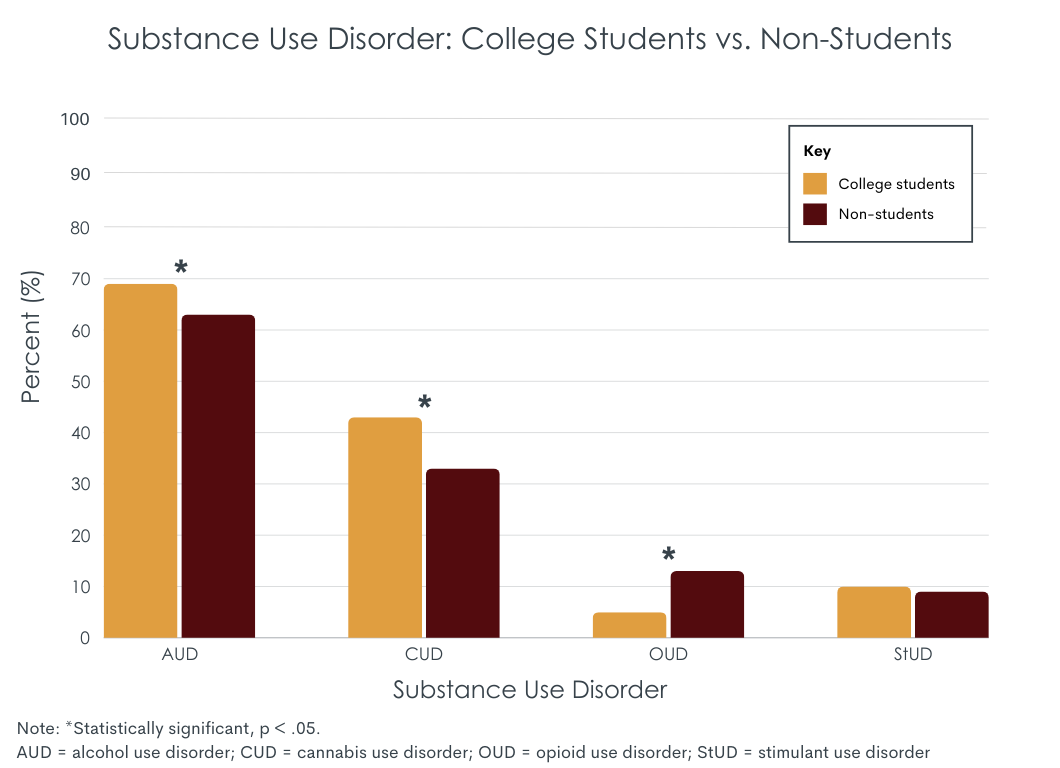

Compared to non-students with substance use disorder, college students with substance use disorder were more likely to endorse past year use of alcohol, cannabis, hallucinogens, and nonmedical prescription stimulants, but less likely to endorse opioid use including heroin and pharmaceutical opioids. College students were also slightly more likely to meet criteria for 2 or more substance use disorders compared to non-students with substance use disorder (23% vs. 20%). College students were more likely to meet criteria for alcohol or cannabis use disorder and less likely to meet criteria for opioid or tranquilizer use disorder. They also tended to have more severe substance use disorders (49% moderate to severe – meaning 4+ criteria out of 11) relative to non-students (40% moderate to severe), on average.

Treatment seeking among college students

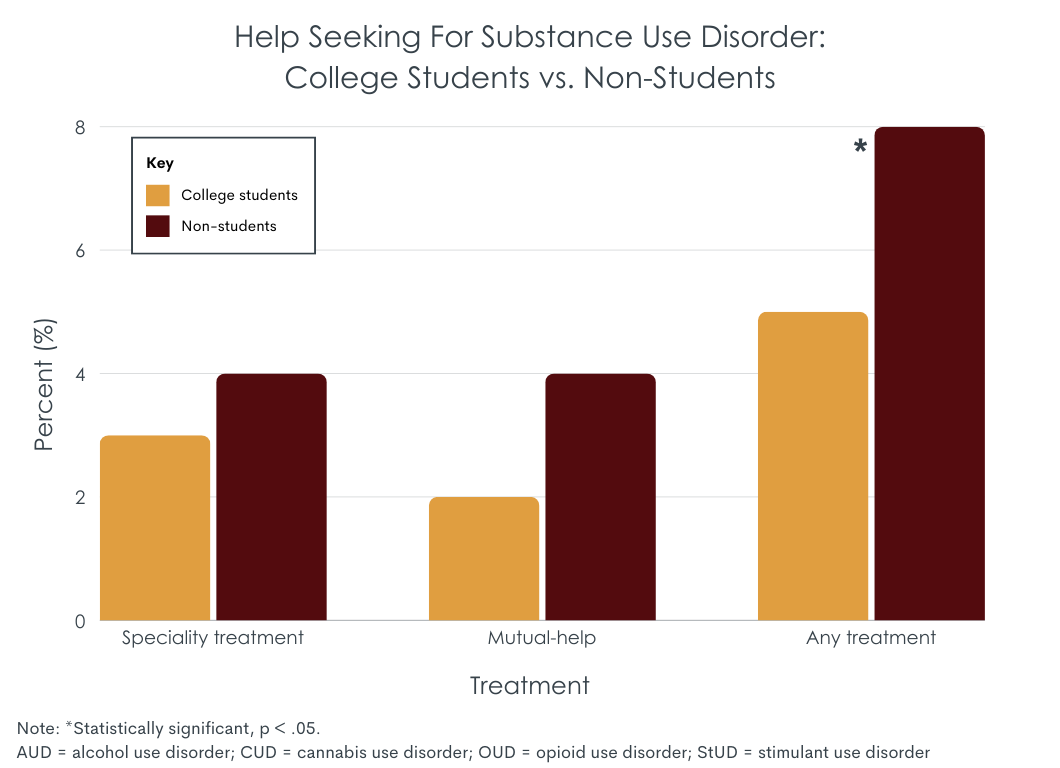

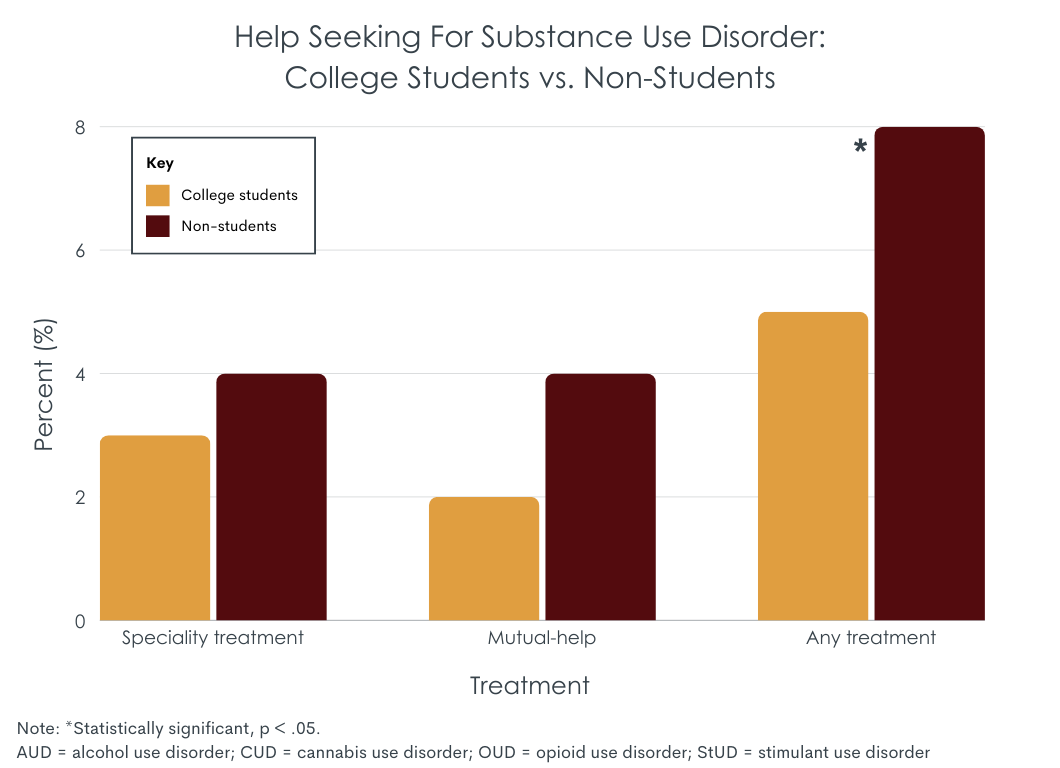

Only 5% of college students with a substance use disorder received treatment for substance use in the past year (defined broadly as “hospital, an inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation facility, a mental health center, an emergency room, a doctor’s office, a carceral facility, a mutual-help group, or in any virtual format”). Compared to those with substance use disorder who did receive treatment, those not receiving treatment tended to be younger, more likely to be undergraduate (relative to graduate) students, enrolled in full-time coursework, and were less likely to be uninsured. Those who received treatment were more likely to have a stimulant, opioid, or tranquilizer use disorder compared to those who did not receive treatment.

Substance use disorder is more prevalent among college student populations (22%) compared to the general population (17%). Despite higher prevalence rates of substance use disorder among college students, fewer college students received treatment than the general population. even while they reported higher levels of moderate/severe substance use disorder.

There are numerous empirically-supported approaches to treating substance use disorder, though the ultimate broader public health impact of such interventions may be decreased because of lower certain groups are hard to engage in care, including but not limited to college students. Data suggests many students are aware of the harms of alcohol or other drugs, thus educational campaigns may be less useful for reducing alcohol or drug use or increasing treatment uptake. At the same time, brief interventions for alcohol use, specifically, have been used to good effect in college students, including Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS) and Alcohol eCheckup to Go (formerly e-CHUG), manualized interventions. These approaches may vary, but generally encourage students to reflect on their drinking, provide information to compare to drinking patterns of their peers (i.e., personalized normative feedback), encourage them to set a reduced drinking goal, and offer tips on how to accomplish that goal. Strategies to address other hazardous substance use apart from alcohol, however, are less widespread on college campuses.

College students often report low motivation to reduce use or engagement with treatment and recovery services. This may be due, in part, possibly to the relatively higher rates of substance use on college campuses and the socially normative demands among college students during this developmental stage to make friends and fit in with others who may be using alcohol/drugs to varying degrees. The past decade has seen a proliferation of interest in an alcohol-free lifestyle, often called the sober curious movement, which includes a growing interest in temporary abstinence challenges like Dry January or Sober October. These temporary challenges present a low stakes opportunity for those with moderate and high levels of alcohol or drug use to explore the effects of abstinence on physical and mental health. For those with more severe substance use disorders, collegiate recovery programs are education-based recovery support services that provide an array of resources (e.g., mutual-help groups, sober social activities, etc.). These and other novel and creative approaches may be additional tools in the public health toolbox to reduce the burden of alcohol harm in the college population.

Relative to a general population, college students are more likely to meet criteria for substance use disorders, but less likely to seek treatment. Some college students, such as younger undergraduates enrolled in full-time coursework may be especially unlikely to attend treatment. Novel, creative approaches to reduce substance use beyond traditional treatment and recovery support services, as has been done for hazardous drinking with BASICS and Alcohol e-Checkup to Go, may help college students find new ways to engage in reducing rates of substance use disorder.

Pasman, E., Blair, L., Solberg, M. A., McCabe, S. E., Schepis, T., & Resko, S. M. (2024). The substance use disorder treatment gap among US college students: Findings from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports, 12. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2024.100279.

l

College students consume alcohol and other drugs at higher rates than the general population, with rates increasing in the past two decades. Though many decrease their use after leaving the college environment – which reinforces higher rates of use through social norms – some persist in these higher levels. With ongoing consequences that interfere with the achievement of important developmental milestones, including academics and employment. Also, those with more substance use during young adulthood (sometimes called “emerging adulthood”) are at greater risk for substance use disorder later in life, highlighting the importance of intervention during this life stage.

Many empirically-supported interventions exist, including cognitive-behavioral therapies, mutual- help groups, and brief interventions. Yet, most students report low motivation to reduce their substance use or to engage with these services. This lower motivation persists despite proliferation of these services’ availability, in addition to a growing national “sober curious” movement. It is possible that in comparison to non-college students with substance use disorder, those in college, on average, are less severe – e.g., experiencing some consequences, but not as many as typically older individuals not in college. Nationally, only a subset of people with substance use disorder receive treatment, with only 13% receiving any form of assistance. There are no estimates of treatment seeking, however, in college students. This study examined updated, nationally representative prevalence rates of substance use disorder and treatment seeking, as well as factors associated with a greater likelihood of attending treatment or mutual-help groups among college students.

This was a cross-sectional analysis of publicly available data from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Curated by the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the survey is administered annually to track trends in prevalence of substance use, mental health, and treatment seeking among American civilians 12 years of age or older.

The current analyses used data from 6,115 people over the age of 16 who reported being currently enrolled in a college or university. The study also examined differences between college students with substance use disorders and 9,138 non-students with substance use disorders. Notably, the comparison sample included non-students of all ages. The researchers were primarily interested in understanding prevalence of substance use disorder, in addition to rates of treatment and mutual-help attendance, among college students.

College students responded to questions about past-year substance use, including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, hallucinogens, and inhalants. If participants endorsed use of a substance, they answered questions assessing diagnostic criteria for that substance use disorder (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Psychiatric Disorders – fifth edition). The researchers classified college students as having a past-year substance use disorder if they met criteria for an alcohol or other drug use disorder (at least two or more symptoms) and/or if they received treatment for substance use in the past year in any setting. This includes in a hospital, an inpatient or outpatient facility, a mental health center, an emergency room, a doctor’s office, a prison/jail, a mutual-help group, or in any virtual format. Treatment setting was categorized as specialty, physical/mental healthcare, mutual-help group, criminal legal system, virtual/telehealth, or any setting, each coded dichotomously as non-mutually exclusive categories, as individuals may have received treatment via multiple settings and modalities. Participants who indicated that they had received treatment for alcohol or other drug use in any setting in the past year were considered to have received “treatment”.

The researchers also examined individuals factors that were associated with being more or less likely to have attended treatment including psychological stress, biological sex (male, female), age (16–20, 21–25, 26+), type of current educational program (graduate, undergraduate), enrollment status (full-time, part- time), insurance (private or combination of public and private, public-only, uninsured), self-identified race or ethnicity (coded as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic multiracial, and Hispanic), and sexual orientation (coded dichotomously as heterosexual or gay/lesbian/bisexual) and use of 2+ substances (i.e., polysubstance use).

The researchers first examined prevalence rates of substance use disorders and differences in key predictor variables between college students with and without substance use disorders. Next, the researchers examined differences in predictor variables between non-student and students with substance use disorders. While the study did not include demographic characteristics of this non-student comparison group, it was weighted like the college student sample. This process maximizes the chances that any observed differences between students and non-students are due to their student status and not some other variable (e.g., where younger individuals typically have fewer substance use disorder symptoms, on average).

Prevalence and predictors of substance use disorder among college students

One in every 5 college students met criteria for a substance use disorder (21.8%). Compared to college students without a substance use disorder, college students who met substance use disorder criteria were older (21-25 compared to 16-20), male, and had more psychological distress. As would be expected, substance use in the past year (e.g., of alcohol, cannabis, opioids, stimulants, etc.) was associated with increased risk of meeting past-year substance use disorder criteria as well.

Students vs non-student peers with substance use disorder

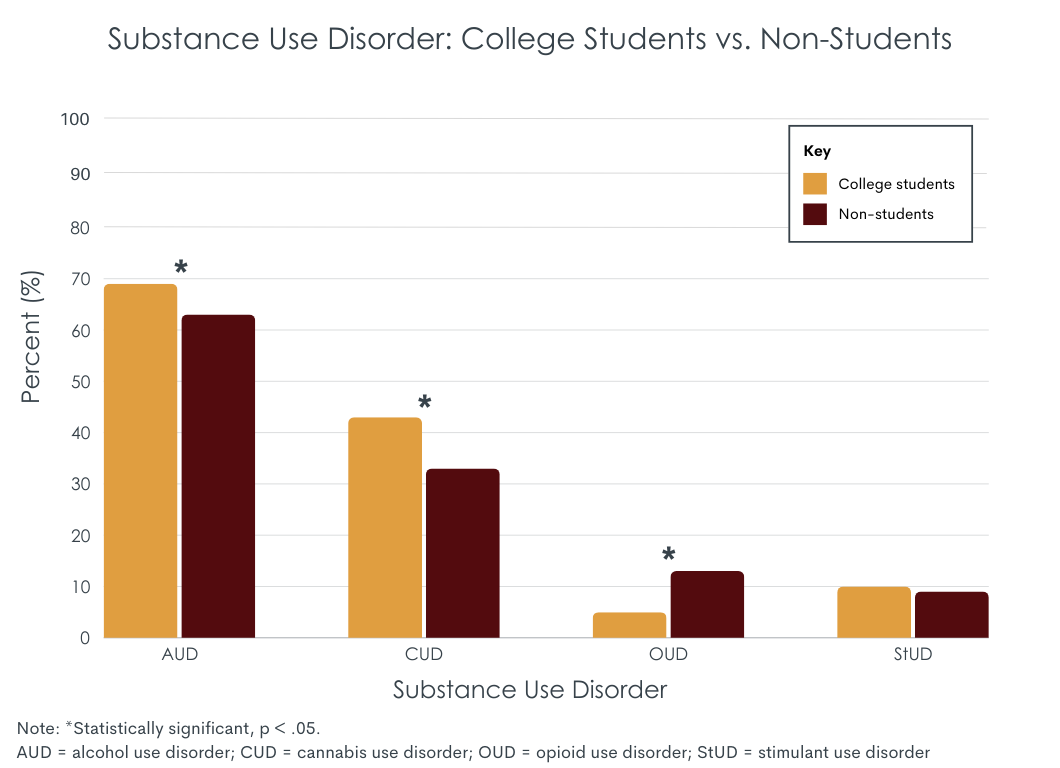

Compared to non-students with substance use disorder, college students with substance use disorder were more likely to endorse past year use of alcohol, cannabis, hallucinogens, and nonmedical prescription stimulants, but less likely to endorse opioid use including heroin and pharmaceutical opioids. College students were also slightly more likely to meet criteria for 2 or more substance use disorders compared to non-students with substance use disorder (23% vs. 20%). College students were more likely to meet criteria for alcohol or cannabis use disorder and less likely to meet criteria for opioid or tranquilizer use disorder. They also tended to have more severe substance use disorders (49% moderate to severe – meaning 4+ criteria out of 11) relative to non-students (40% moderate to severe), on average.

Treatment seeking among college students

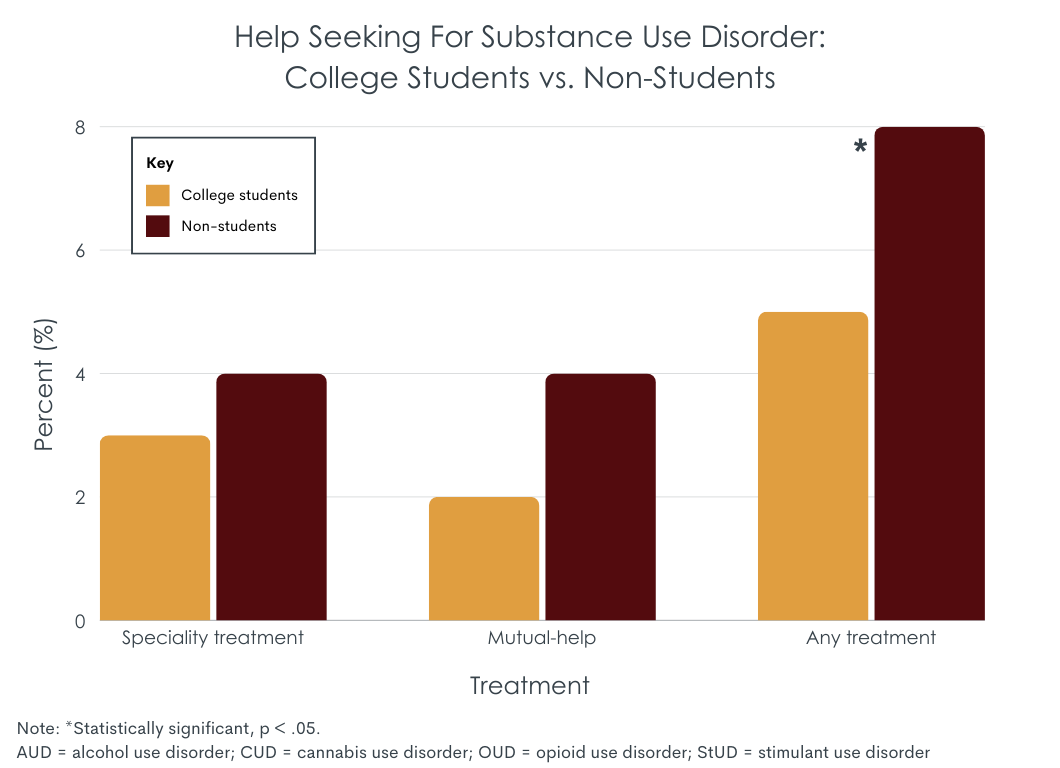

Only 5% of college students with a substance use disorder received treatment for substance use in the past year (defined broadly as “hospital, an inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation facility, a mental health center, an emergency room, a doctor’s office, a carceral facility, a mutual-help group, or in any virtual format”). Compared to those with substance use disorder who did receive treatment, those not receiving treatment tended to be younger, more likely to be undergraduate (relative to graduate) students, enrolled in full-time coursework, and were less likely to be uninsured. Those who received treatment were more likely to have a stimulant, opioid, or tranquilizer use disorder compared to those who did not receive treatment.

Substance use disorder is more prevalent among college student populations (22%) compared to the general population (17%). Despite higher prevalence rates of substance use disorder among college students, fewer college students received treatment than the general population. even while they reported higher levels of moderate/severe substance use disorder.

There are numerous empirically-supported approaches to treating substance use disorder, though the ultimate broader public health impact of such interventions may be decreased because of lower certain groups are hard to engage in care, including but not limited to college students. Data suggests many students are aware of the harms of alcohol or other drugs, thus educational campaigns may be less useful for reducing alcohol or drug use or increasing treatment uptake. At the same time, brief interventions for alcohol use, specifically, have been used to good effect in college students, including Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS) and Alcohol eCheckup to Go (formerly e-CHUG), manualized interventions. These approaches may vary, but generally encourage students to reflect on their drinking, provide information to compare to drinking patterns of their peers (i.e., personalized normative feedback), encourage them to set a reduced drinking goal, and offer tips on how to accomplish that goal. Strategies to address other hazardous substance use apart from alcohol, however, are less widespread on college campuses.

College students often report low motivation to reduce use or engagement with treatment and recovery services. This may be due, in part, possibly to the relatively higher rates of substance use on college campuses and the socially normative demands among college students during this developmental stage to make friends and fit in with others who may be using alcohol/drugs to varying degrees. The past decade has seen a proliferation of interest in an alcohol-free lifestyle, often called the sober curious movement, which includes a growing interest in temporary abstinence challenges like Dry January or Sober October. These temporary challenges present a low stakes opportunity for those with moderate and high levels of alcohol or drug use to explore the effects of abstinence on physical and mental health. For those with more severe substance use disorders, collegiate recovery programs are education-based recovery support services that provide an array of resources (e.g., mutual-help groups, sober social activities, etc.). These and other novel and creative approaches may be additional tools in the public health toolbox to reduce the burden of alcohol harm in the college population.

Relative to a general population, college students are more likely to meet criteria for substance use disorders, but less likely to seek treatment. Some college students, such as younger undergraduates enrolled in full-time coursework may be especially unlikely to attend treatment. Novel, creative approaches to reduce substance use beyond traditional treatment and recovery support services, as has been done for hazardous drinking with BASICS and Alcohol e-Checkup to Go, may help college students find new ways to engage in reducing rates of substance use disorder.

Pasman, E., Blair, L., Solberg, M. A., McCabe, S. E., Schepis, T., & Resko, S. M. (2024). The substance use disorder treatment gap among US college students: Findings from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports, 12. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2024.100279.

l

College students consume alcohol and other drugs at higher rates than the general population, with rates increasing in the past two decades. Though many decrease their use after leaving the college environment – which reinforces higher rates of use through social norms – some persist in these higher levels. With ongoing consequences that interfere with the achievement of important developmental milestones, including academics and employment. Also, those with more substance use during young adulthood (sometimes called “emerging adulthood”) are at greater risk for substance use disorder later in life, highlighting the importance of intervention during this life stage.

Many empirically-supported interventions exist, including cognitive-behavioral therapies, mutual- help groups, and brief interventions. Yet, most students report low motivation to reduce their substance use or to engage with these services. This lower motivation persists despite proliferation of these services’ availability, in addition to a growing national “sober curious” movement. It is possible that in comparison to non-college students with substance use disorder, those in college, on average, are less severe – e.g., experiencing some consequences, but not as many as typically older individuals not in college. Nationally, only a subset of people with substance use disorder receive treatment, with only 13% receiving any form of assistance. There are no estimates of treatment seeking, however, in college students. This study examined updated, nationally representative prevalence rates of substance use disorder and treatment seeking, as well as factors associated with a greater likelihood of attending treatment or mutual-help groups among college students.

This was a cross-sectional analysis of publicly available data from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Curated by the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the survey is administered annually to track trends in prevalence of substance use, mental health, and treatment seeking among American civilians 12 years of age or older.

The current analyses used data from 6,115 people over the age of 16 who reported being currently enrolled in a college or university. The study also examined differences between college students with substance use disorders and 9,138 non-students with substance use disorders. Notably, the comparison sample included non-students of all ages. The researchers were primarily interested in understanding prevalence of substance use disorder, in addition to rates of treatment and mutual-help attendance, among college students.

College students responded to questions about past-year substance use, including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, hallucinogens, and inhalants. If participants endorsed use of a substance, they answered questions assessing diagnostic criteria for that substance use disorder (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Psychiatric Disorders – fifth edition). The researchers classified college students as having a past-year substance use disorder if they met criteria for an alcohol or other drug use disorder (at least two or more symptoms) and/or if they received treatment for substance use in the past year in any setting. This includes in a hospital, an inpatient or outpatient facility, a mental health center, an emergency room, a doctor’s office, a prison/jail, a mutual-help group, or in any virtual format. Treatment setting was categorized as specialty, physical/mental healthcare, mutual-help group, criminal legal system, virtual/telehealth, or any setting, each coded dichotomously as non-mutually exclusive categories, as individuals may have received treatment via multiple settings and modalities. Participants who indicated that they had received treatment for alcohol or other drug use in any setting in the past year were considered to have received “treatment”.

The researchers also examined individuals factors that were associated with being more or less likely to have attended treatment including psychological stress, biological sex (male, female), age (16–20, 21–25, 26+), type of current educational program (graduate, undergraduate), enrollment status (full-time, part- time), insurance (private or combination of public and private, public-only, uninsured), self-identified race or ethnicity (coded as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic multiracial, and Hispanic), and sexual orientation (coded dichotomously as heterosexual or gay/lesbian/bisexual) and use of 2+ substances (i.e., polysubstance use).

The researchers first examined prevalence rates of substance use disorders and differences in key predictor variables between college students with and without substance use disorders. Next, the researchers examined differences in predictor variables between non-student and students with substance use disorders. While the study did not include demographic characteristics of this non-student comparison group, it was weighted like the college student sample. This process maximizes the chances that any observed differences between students and non-students are due to their student status and not some other variable (e.g., where younger individuals typically have fewer substance use disorder symptoms, on average).

Prevalence and predictors of substance use disorder among college students

One in every 5 college students met criteria for a substance use disorder (21.8%). Compared to college students without a substance use disorder, college students who met substance use disorder criteria were older (21-25 compared to 16-20), male, and had more psychological distress. As would be expected, substance use in the past year (e.g., of alcohol, cannabis, opioids, stimulants, etc.) was associated with increased risk of meeting past-year substance use disorder criteria as well.

Students vs non-student peers with substance use disorder

Compared to non-students with substance use disorder, college students with substance use disorder were more likely to endorse past year use of alcohol, cannabis, hallucinogens, and nonmedical prescription stimulants, but less likely to endorse opioid use including heroin and pharmaceutical opioids. College students were also slightly more likely to meet criteria for 2 or more substance use disorders compared to non-students with substance use disorder (23% vs. 20%). College students were more likely to meet criteria for alcohol or cannabis use disorder and less likely to meet criteria for opioid or tranquilizer use disorder. They also tended to have more severe substance use disorders (49% moderate to severe – meaning 4+ criteria out of 11) relative to non-students (40% moderate to severe), on average.

Treatment seeking among college students

Only 5% of college students with a substance use disorder received treatment for substance use in the past year (defined broadly as “hospital, an inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation facility, a mental health center, an emergency room, a doctor’s office, a carceral facility, a mutual-help group, or in any virtual format”). Compared to those with substance use disorder who did receive treatment, those not receiving treatment tended to be younger, more likely to be undergraduate (relative to graduate) students, enrolled in full-time coursework, and were less likely to be uninsured. Those who received treatment were more likely to have a stimulant, opioid, or tranquilizer use disorder compared to those who did not receive treatment.

Substance use disorder is more prevalent among college student populations (22%) compared to the general population (17%). Despite higher prevalence rates of substance use disorder among college students, fewer college students received treatment than the general population. even while they reported higher levels of moderate/severe substance use disorder.

There are numerous empirically-supported approaches to treating substance use disorder, though the ultimate broader public health impact of such interventions may be decreased because of lower certain groups are hard to engage in care, including but not limited to college students. Data suggests many students are aware of the harms of alcohol or other drugs, thus educational campaigns may be less useful for reducing alcohol or drug use or increasing treatment uptake. At the same time, brief interventions for alcohol use, specifically, have been used to good effect in college students, including Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS) and Alcohol eCheckup to Go (formerly e-CHUG), manualized interventions. These approaches may vary, but generally encourage students to reflect on their drinking, provide information to compare to drinking patterns of their peers (i.e., personalized normative feedback), encourage them to set a reduced drinking goal, and offer tips on how to accomplish that goal. Strategies to address other hazardous substance use apart from alcohol, however, are less widespread on college campuses.

College students often report low motivation to reduce use or engagement with treatment and recovery services. This may be due, in part, possibly to the relatively higher rates of substance use on college campuses and the socially normative demands among college students during this developmental stage to make friends and fit in with others who may be using alcohol/drugs to varying degrees. The past decade has seen a proliferation of interest in an alcohol-free lifestyle, often called the sober curious movement, which includes a growing interest in temporary abstinence challenges like Dry January or Sober October. These temporary challenges present a low stakes opportunity for those with moderate and high levels of alcohol or drug use to explore the effects of abstinence on physical and mental health. For those with more severe substance use disorders, collegiate recovery programs are education-based recovery support services that provide an array of resources (e.g., mutual-help groups, sober social activities, etc.). These and other novel and creative approaches may be additional tools in the public health toolbox to reduce the burden of alcohol harm in the college population.

Relative to a general population, college students are more likely to meet criteria for substance use disorders, but less likely to seek treatment. Some college students, such as younger undergraduates enrolled in full-time coursework may be especially unlikely to attend treatment. Novel, creative approaches to reduce substance use beyond traditional treatment and recovery support services, as has been done for hazardous drinking with BASICS and Alcohol e-Checkup to Go, may help college students find new ways to engage in reducing rates of substance use disorder.

Pasman, E., Blair, L., Solberg, M. A., McCabe, S. E., Schepis, T., & Resko, S. M. (2024). The substance use disorder treatment gap among US college students: Findings from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports, 12. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2024.100279.