Combining skills training with peer support and mentoring improves outcomes for people with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder

Formal peer recovery support interventions involve services, guidance, and mentorship by specially trained individuals with lived experience of substance use and/or mental illness. This type of support may be especially useful to people with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders who often face unique challenges initiating and sustaining recovery. In this study, the researchers examined whether adding a peer-led recovery support program to a skills training program improved mental health and substance use outcomes for people with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

People with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders warrant special attention given the severity of their psychological and social challenges. Critically, people with more severe mental health conditions that accompany a substance use disorder tend not to benefit as much from conventional treatment as those with less severe co-occurring mental health conditions over the long-term. The added cognitive burden of severe mental illness and its related impairments on individuals’ day-to-day functioning may make it harder to develop insight and incorporate new skills learned in treatment. These individuals may benefit from targeted approaches to increase their recovery capital, the internal and external resources individuals can use to help initiate and sustain recovery over time.

Peer support interventions are being developed and disseminated across the U.S. in both community-based and professional-clinical health care settings. By targeting enhanced recovery capital and helping individuals actively navigate the demands of early recovery, these interventions show promise for individuals with substance use disorder as well as those with serious mental illnesses, including psychotic disorders like schizophrenia.

In this study, the researchers investigated whether adding a peer support intervention to manualized skills training provided extra benefit for adults with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder after an inpatient hospital stay.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

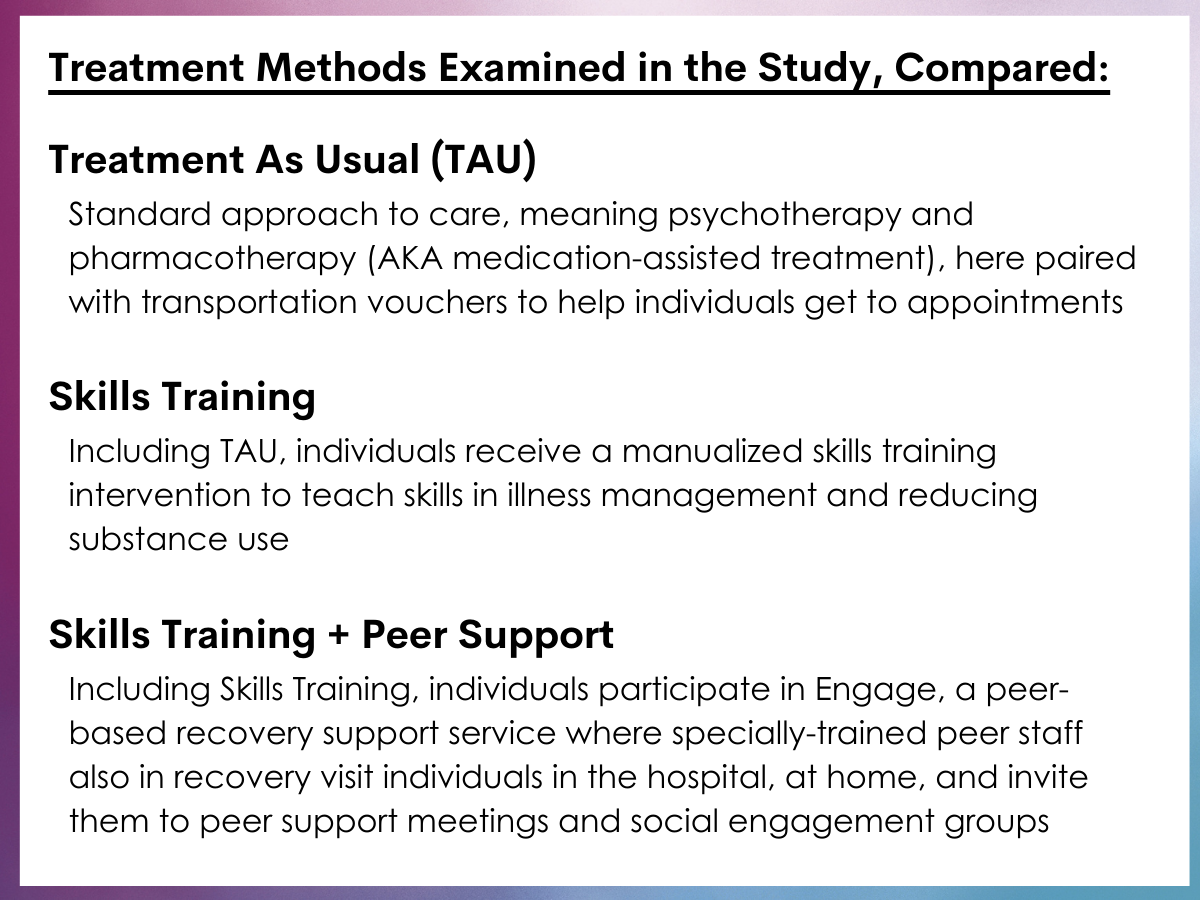

This study was a randomized trial with 137 participants randomized to one of 3 conditions: skills training only (47 participants), skills training plus a peer support intervention called “Engage” (42 participants), or treatment as usual (47 participants). The treatment as usual condition included standard care and transportation vouchers to help participants attend outpatient appointments. The skills training only condition included standard care, transportation vouchers, and a manualized skills training intervention for people with co-occurring disorders. The skills training with Engage condition included skills training plus a peer-led social engagement program. Primary outcomes included: 1) positive and negative symptoms of psychosis, 2) social functioning measured by a scale that targeted personal competence and social activity, 3) depressive symptoms defined in this study with three factors including dependency (themes of abandonment; feeling lonely and helpless; wanting to be close to, related to, and dependent upon others), self-criticism (themes of guilt, emptiness, hopelessness, dissatisfaction, and insecurity), and efficacy (themes of high standards and personal goals; responsibility; inner strength; feelings of independence, satisfaction, pride in one’s accomplishments), and 4) alcohol use measured by the number of days drinking in the past 30 days, experiencing alcohol-related problems in the past 30 days, and a 3-point rating of the importance of getting treatment for alcohol problems. Secondary outcomes included inpatient hospitalizations and outpatient treatment utilization. To collect data on psychiatric, social functioning, and alcohol-related outcomes, research assistants conducted follow-up assessments with participants at baseline, 3 months, and 9 months. Based on hospital system data, healthcare utilization outcomes were measured at 6 months and 12 months.

Participants were individuals diagnosed with co-occurring psychotic and substance use disorders based on structured clinical interviews recruited from inpatient services at the Yale-New Haven Psychiatric Hospital or Connecticut Mental Health Center with one prior hospital admission in the previous year.

Skills training was offered as needed in inpatient services and weekly in the outpatient clinic of the mental health center. Participants were invited to participate during the 3 months following discharge and encouraged to continue afterward if they were interested. Based on skills training approaches to reducing substance use and illness management approaches for psychosis, the 2 evidence-based manuals included education on the importance of continuing pharmacotherapy, instruction on life skill techniques (e.g., daily routine cues to help remember medication dosing times), and weekly feedback sessions. Additional discussions were held to review key themes, including experiences with medication, psychiatric symptoms, link between adherence and improvement, goals for treatment, and reassurance.

Treatment methods examined in the study, compared.

In the Engage condition, social engagement activities were offered during the 3 months following discharge. While participants were in inpatient services, peer staff members made visits and invited participants to join the Engage program. Once participants left the hospital, they received home visits from the peer staff member. Participants were invited to twice-weekly mutual support groups, which were held outside of the mental health center at a community location and included free lunch once per week. These meetings concentrated on promoting mutual support among members, inspiring hope for recovery, and exemplifying self-care. Participants were also invited to social and recreational outings. By their 3-month graduation from the program, participants were invited to transition into a “graduation” group that met once per week at a local social club. Peer staff members also offered to join participants in attending meetings for abstinence-based mutual-help groups in the community, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, and helping them obtain sponsors.

The sample was 38 years old, on average, and had 11 years of education (less than high school degree). The majority of participants were male (66%), African-American (58%), never married (68%), and unemployed (85%). There were no significant differences in participants’ demographic characteristics across study conditions.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Participants in both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions showed similar reductions in positive and negative psychotic symptoms.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in both the skills training only condition and skills training plus Engage conditions had similar levels of positive psychotic symptoms at 3 months, while both groups showed an increase at 9 months.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in the skills training only condition showed a reduction in negative psychotic symptoms at 3 months, although this benefit did not persist at 9 months. Participants in the skills training plus Engage condition had similar negative psychotic symptoms as the treatment as usual group over time.

Participants in both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions exhibited beneficial improvements in social functioning and some depression symptoms.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions had similar social functioning at 3 months, but showed an improvement by the 9-month follow-up.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions showed an increase in self-criticism at 3 months, though levels were similar at 9 months.

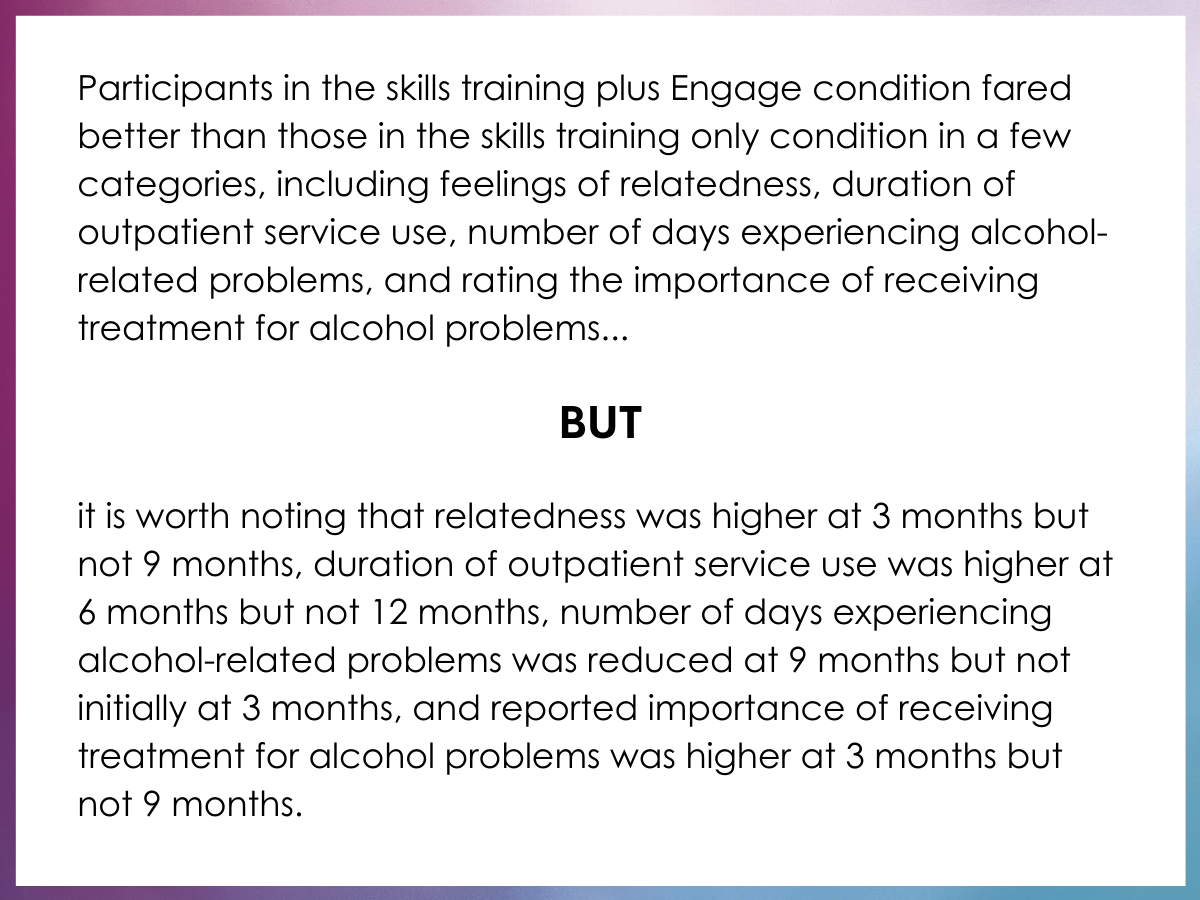

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in the skills training plus Engage condition showed an increase in relatedness at 3 months, which did not persist at 9 months. Participants in the skills training only condition had similar levels of relatedness over time as the treatment as usual group.

Participants in both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions showed improvements in accessing inpatient and outpatient health care.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions had fewer hospital readmissions at 6 months and 12 months.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in the skills training plus Engage condition had a higher duration of outpatient service use at 6 months, which did not persist at 12 months. Participants in the skills training only condition had similar outpatient service use as those in the treatment as usual group.

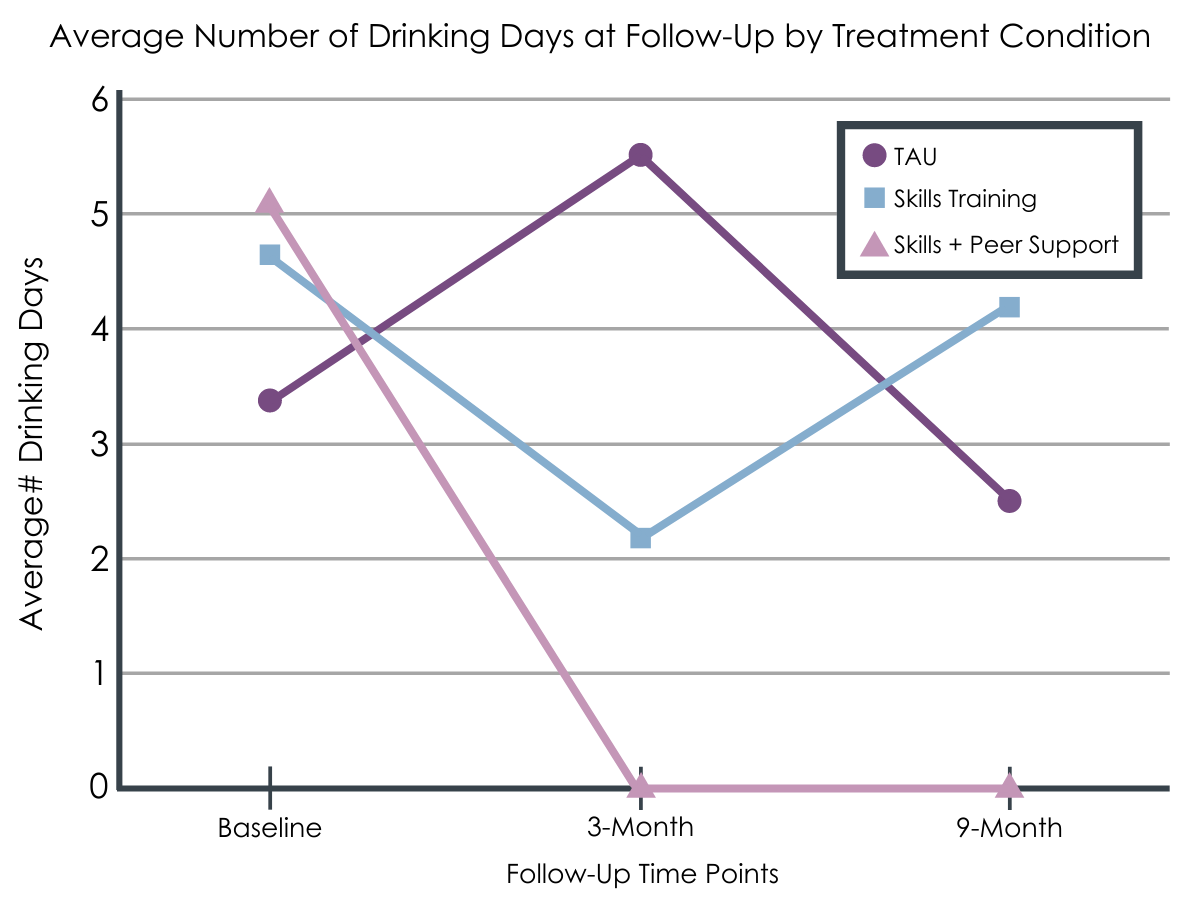

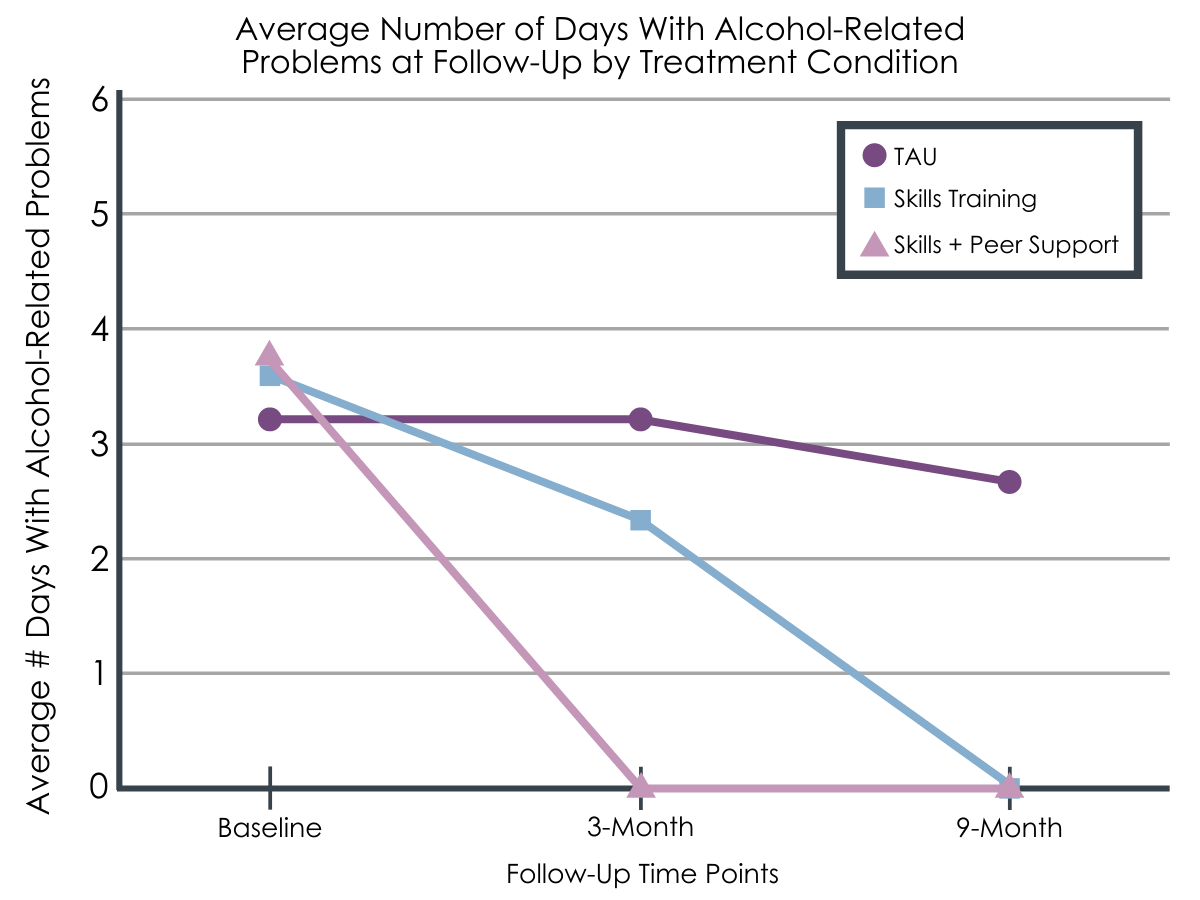

Participants in both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions spent fewer days drinking and experiencing alcohol-related problems.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions showed reductions in drinking days at 3 months, though these improvements did not persist at 9 months.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in the skills training plus Engage condition had similar numbers of days experiencing alcohol-related problems at 3 months, but showed a reduction at 9 months.

Compared to treatment as usual, participants in the skills training plus Engage condition showed an increase in rating the importance of receiving treatment for alcohol problems at 3 months, which did not persist at 9 months.

Notably, participants in the skills training plus Engage condition fared better than those in the skills training only condition in a few categories, including feelings of relatedness, duration of outpatient service use, number of days experiencing alcohol-related problems, and rating the importance of receiving treatment for alcohol problems.

Participants in the skills training only condition fared better than those in the skills training plus Engage condition in one category, which was negative psychotic symptoms.

Average number of drinking days at follow-up by treatment condition.

Average number of days with alcohol-related problems at follow-up by treatment condition.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study was the first randomized trial to provide empirical evidence on the additional benefit of peer support when offered alongside conventional care and manualized skills training, among people with co-occurring psychotic and substance use disorders.

In this study, the researchers found that, compared to treatment as usual, skills training was effective in reducing negative symptoms of psychosis and alcohol use in the short term, as well as reducing positive symptoms of psychosis, reducing hospital admissions, and improving social functioning over the long term.

The researchers also found that the addition of the peer support intervention was effective in increasing relatedness, self-criticism, and outpatient service use in the short term. These results are consistent with findings from another study showing that interacting with peer staff led to increases in relatedness, self-criticism, and engagement in outpatient care, compared to interacting with traditional providers. The researchers suggest that simultaneous increases in relatedness and self-criticism may be attributed to participants’ sense that peer staff offered supportive relationships while also holding high expectations for them. Whether increased self-criticism is helpful or harmful to individuals’ recovery and other health outcomes is an important empirical question for future research.

Most importantly, both skills training conditions showed reductions in alcohol use in the short term, although these gains were not sustained over the long term. Beneficial reductions in the number of days drinking alcohol were observed in both skills training conditions, which suggests that this improvement was not attributable to the social engagement program.

Notably, having peer staff members conduct social engagement activities led to additional benefits that were not observed with skills training alone. The peer-led social engagement program demonstrated promising alcohol-related outcomes, including a reduction in the number of days experiencing alcohol-related problems and an increase in rating the importance of getting treatment for alcohol problems. These results align with a previous study which found that peer-led support was associated with a reduction in alcohol-related problems among people with co-occurring disorders with a history of criminal justice involvement. Further research is needed to confirm that these additional gains are specifically attributable to peer staff and their first-hand experiences of serious mental illness and/or substance use disorder.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- There was a high rate of attrition among study participants at each assessment timepoint, especially from baseline to the first follow-up assessment at 3 months. Attrition is not unusual for people with co-occurring disorders, because they are more likely to have unstable housing situations and may resist efforts to connect with services.

- Although the rate of attrition was uniform across the 3 conditions, the researchers did not test for group differences across conditions. Changes in demographic and clinical characteristics due to attrition may have affected the generalizability of the study’s findings.

- Based on the study’s design, the researchers were unable to determine whether the added benefit of the social engagement activities – when present – was explained by the leadership of a peer in recovery, engaging in the activities in which they were encouraged to participate, or some other factors.

BOTTOM LINE

In this study, the researchers examined the effect of skills training and a peer-led social engagement program on psychosis symptoms, social functioning, substance use, and healthcare utilization among people with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder.

The researchers found that both the skills training only and skills training plus Engage conditions led to reduced positive psychotic symptoms (short term), increased levels of self-criticism (long term); improved social functioning (short term); reduced hospital readmissions (short and long term); and reduced number of days drinking alcohol (short term). Interestingly, the skills training only condition reduced negative psychotic symptoms (short term).

Most importantly, adding the peer-led social engagement program to the skills training condition led to increased duration of outpatient treatment (short term); reduced number of days experiencing alcohol-related problems (long term); and increased rating of importance of getting treatment for alcohol problems (short term).

These promising findings are consistent with anecdotal, theoretical, and qualitative evidence for the added benefit of peer support across several psychosis- and alcohol-related outcomes, particularly among people with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Skills training is a beneficial treatment option for people with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder, which can contribute to improvements in psychosis and depression symptoms, social functioning, healthcare utilization, and number of drinking days. Furthermore, skills training paired with a peer-led social engagement program may be a promising option for sustaining additional alcohol-related benefits, including an increase in the self-rated importance of getting treatment for alcohol problems over the short term, reduction in the number of days experiencing alcohol-related problems over the long term, and an increase in the duration of outpatient treatment over the short term.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Skills training is a promising treatment option for people with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder, which may lead to improvements in psychosis and depression symptoms, social functioning, and healthcare utilization. Most importantly, skills training can lead to a reduction in the number of drinking days in the short term. Offering patients a skills training intervention paired with a peer-led social engagement program may be a helpful option for sustaining additional alcohol- and healthcare-related benefits, including an increase in the self-rated importance of getting treatment for alcohol problems over the short term, reduction in the number of days experiencing alcohol-related problems over the long term, and an increase in the duration of outpatient treatment over the short term.

- For scientists: Skills training is a promising treatment option for people with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder, which can contribute to improvements in psychosis and depression symptoms, social functioning, healthcare utilization, and number of drinking days. Furthermore, skills training paired with a peer-led social engagement program may be a helpful option for sustaining additional alcohol- and healthcare-related benefits, including an increase in the self-rated importance of getting treatment for alcohol problems over the short term, reduction in the number of days experiencing alcohol-related problems over the long term, and an increase in the duration of outpatient treatment over the short term. Further research is needed to determine whether these positive effects are attributable to the involvement of peer support, social engagement activities offered to participants, or some other factors.

- For policy makers: Skills training is a beneficial treatment option for people with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder, which can contribute to improvements in psychosis and depression symptoms, social functioning, healthcare utilization, and number of drinking days. Furthermore, skills training paired with a peer-led social engagement program may be a promising option for sustaining additional alcohol- and healthcare-related benefits, including an increase in the self-rated importance of getting treatment for alcohol problems over the short term, reduction in the number of days experiencing alcohol-related problems over the long term, and an increase in the duration of outpatient treatment over the short term. Providing funding for outpatient clinics to hire peer staff members that engage people with co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder in social engagement activities would be a meaningful step toward facilitating long-term reductions in alcohol use and improving healthcare utilization.

CITATIONS

O’Connell, M., Flanagan, E.H., Delphin-Rittmon, M.E., & Davidson, L. (2020). Enhancing outcomes for persons with co-occurring disorders through skills training and peer recovery support. Journal of Mental Health, 29, 6-11. DOI: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1294733