There are many pathways to recovery from substance use disorder, but do all recovery pathways lead to the same destination? Examining over 9,000 individuals, this study sought to understand the shared markers of success in the recovery process.

There are many pathways to recovery from substance use disorder, but do all recovery pathways lead to the same destination? Examining over 9,000 individuals, this study sought to understand the shared markers of success in the recovery process.

l

From a scientific perspective, recovery from substance use disorder is conceptualized not just in terms of substance use, but as a multifaceted process of ongoing personal development, aiming for sustained improvements in all areas of life. While there have been many attempts to “define” recovery, multiple pathways (e.g., abstinence vs. non-abstinence; assisted vs. unassisted etc.) and multiple settings (e.g., community vs. clinical vs. neither) suggest recovery processes are conditional on individual and contextual factors.

Rather than imposing a top-down definition of recovery, this study considered the collective voices of individuals with lived recovery experience, aiming to forge an empirical, shared understanding of the term. Through the analysis of existing data from the “What Is Recovery?” study, this research sought to identify the common ground among recovery experiences, regardless of the individual paths taken. It is an exploratory study, aiming to distill the essence of recovery by individuals with direct lived experience, and in turn, to inform and refine conceptual frameworks used by institutions and the design of substance use disorder services and research.

This was a cross-sectional survey, meaning it provides a snapshot of information about the population at that specific moment, allowing researchers to analyze relationships between variables or characteristics without the need for follow-up over time. It drew responses from 9,341 individuals recruited directly from a varied group of recovery organizations who self-identified as being “in recovery”, “recovered”, “in medication-assisted recovery”, or as “having had a problem with alcohol or drugs but [who] no longer do”.

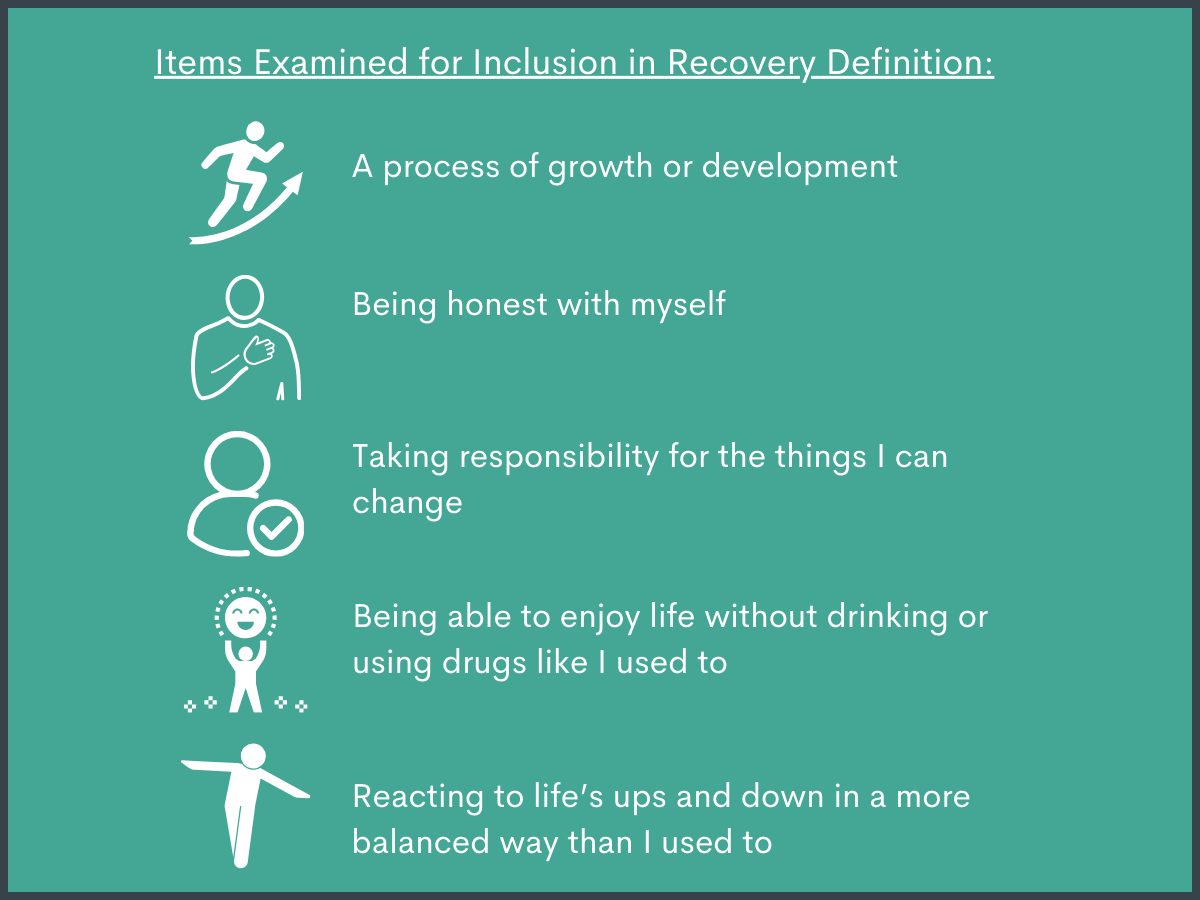

Study staff recruited participants from over 200 research partners ranging from treatment programs to recovery organizations, in addition to outreach through various media and personal networks. Among these sources, the study included 12% from recovery organizations (e.g., Faces and Voices of Recovery), 12% from mutual-help organizations, 12% from treatment and alumni groups, 24% from general study announcements in various outlets, 15% from “word of mouth”, and 24% from other sources. Participants from around the globe, with a small percentage outside the U.S., completed a comprehensive 47-item survey. This survey probed a spectrum of recovery dimensions (see figure below), allowing participants to convey whether an element “definitely belongs” in one’s definition of recovery, “somewhat belongs”, “does not belong in your definition of recovery but may belong in other people’s definition of recovery”, or “does not really belong in a definition of recovery” across domains such as abstinence, life essentials, enrichment, and spirituality. The survey utilized a technique to distill complex survey responses into core themes. This method helped reveal underlying patterns in how individuals define their own recoveries, reducing the broad array of survey items into more manageable groups of related concepts. By doing so, the researchers could identify the most central elements to recovery as consistently understood by a diverse group of participants with lived experience.

The study also examined whether endorsed elements were consistent across sociodemographic variables, substance use problem characteristics, help-seeking history, and severity of substance use disorders as defined by the DSM-5. In analyzing the data, the team defined 30 distinct subgroups based on these variables to assess the commonality and centrality of various recovery elements to establish a shared and empirically grounded framework of recovery that resonates with the broadest spectrum of individuals on their recovery journey.

Core recovery elements mapped onto both personal growth and substance use processes

The study identified core elements crucial to recovery, each endorsed by at least 80% of respondents and consistently ranked among the top 10 across 30 subgroups. These elements include Personal Growth, highlighted by 94.5% of participants, indicating a universal aspiration for personal development. Personal Integrity, comprising honesty with oneself (93.2%) and taking responsibility (92.4%), emphasizes self-reflection and accountability. Additionally, Emotional Balance was deemed crucial by 91.4% of respondents, underlining the importance of resilience in navigating life’s challenges.

Certain elements prevailed across most subgroups. Joy and Emotional Coping were endorsed by over 90% of participants, emphasizing the significance of emotional well-being in recovery. Additionally, Abstinence and Moderation were recognized by 90.1%, indicating a shift towards moderation alongside traditional abstinence approaches.

Some elements were unique to certain recovery pathways

Unique recovery definitions surfaced among subgroups with milder substance use disorder severity, non-abstinent recovery pathways, or no history of specialty treatment or mutual-help group involvement. For instance, those in non-abstinent recovery emphasized taking responsibility, suggesting a preference for self-reliance in this subgroup.

Participants receiving medication for opioid use disorder prioritized aspects of physical health, reflecting a medicalized view of substance use disorder resolution influenced by severe health consequences associated with opioid use.

Those with experience in “second wave” mutual-help organizations – sometimes called 12-step “alternatives” (e.g., SMART Recovery) emphasized enjoying life without substances (92% endorsement) and mental health care, aligning with the psychological framing of addiction treatment in such programs.

The recent study sheds light on the common elements perceived as central to recovery by individuals who have experienced alcohol and other drug problems. It analyzed responses from a national survey, defining “core” elements of recovery as those most commonly endorsed by respondents and consistent across diverse subgroups. Four key elements emerged: personal growth, personal integrity (including honesty and responsibility), and emotional balance. Furthermore, the ability to find joy and manage emotions without substances, and commitment to nonproblematic use or abstinence, were prevalent among the majority. This suggests, unsurprisingly given the study’s focus on recovery from substance use disorder, that substance use goals are important to the vast majority of those in recovery.

These findings are consistent with established recovery concepts that frame it as a dynamic process of change, involving self-improvement and improved emotional self-regulation. Notably, the study introduces honesty and responsibility as potential new dimensions for formal recovery definitions. The consensus on the importance of substance use goals, includes – but is not limited to – abstinence. Notably, central definitions also included, implicitly, developing strategies to enjoy life and handle unpleasant emotions without “using drugs or drinking like I used to”.

Divergent recovery experiences and needs were noted among subgroups with milder substance use disorder severity or those not involved in traditional treatment or support groups, emphasizing self-reliance. For those in medication-assisted recovery, physical health was a significant focus, reflecting a medical perspective on recovery. In contrast, individuals with experience in second-wave mutual-help organizations like SMART Recovery highlighted psychological health and enjoyment of life without substances, aligning potentially with a psychological understanding of addiction treatment within these programs.

This study offers a nuanced view of recovery, emphasizing it as a multifaceted process involving growth, personal integrity, and balanced reactions to life’s challenges. The most common elements of recovery across subgroups included enjoying life and handling negative emotions without substance use, while contributing positively to society.

Zemore, S. E., Ziemer, K. L., Gilbert, P. A., Karno, M. P., & Kaskutas, L. A. (2023). Understanding the shared meaning of recovery from substance use disorders: New findings from the What is Recovery? Study. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/11782218231199372

l

From a scientific perspective, recovery from substance use disorder is conceptualized not just in terms of substance use, but as a multifaceted process of ongoing personal development, aiming for sustained improvements in all areas of life. While there have been many attempts to “define” recovery, multiple pathways (e.g., abstinence vs. non-abstinence; assisted vs. unassisted etc.) and multiple settings (e.g., community vs. clinical vs. neither) suggest recovery processes are conditional on individual and contextual factors.

Rather than imposing a top-down definition of recovery, this study considered the collective voices of individuals with lived recovery experience, aiming to forge an empirical, shared understanding of the term. Through the analysis of existing data from the “What Is Recovery?” study, this research sought to identify the common ground among recovery experiences, regardless of the individual paths taken. It is an exploratory study, aiming to distill the essence of recovery by individuals with direct lived experience, and in turn, to inform and refine conceptual frameworks used by institutions and the design of substance use disorder services and research.

This was a cross-sectional survey, meaning it provides a snapshot of information about the population at that specific moment, allowing researchers to analyze relationships between variables or characteristics without the need for follow-up over time. It drew responses from 9,341 individuals recruited directly from a varied group of recovery organizations who self-identified as being “in recovery”, “recovered”, “in medication-assisted recovery”, or as “having had a problem with alcohol or drugs but [who] no longer do”.

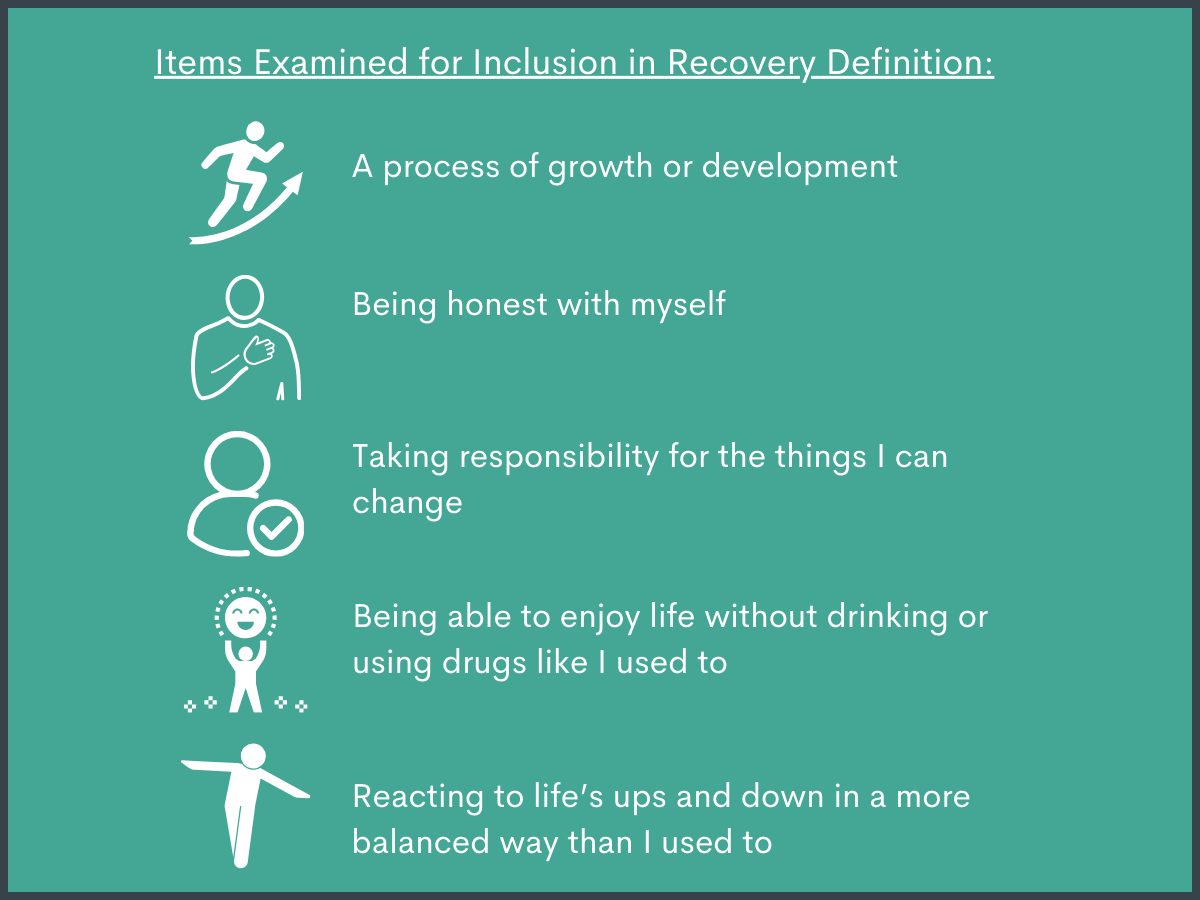

Study staff recruited participants from over 200 research partners ranging from treatment programs to recovery organizations, in addition to outreach through various media and personal networks. Among these sources, the study included 12% from recovery organizations (e.g., Faces and Voices of Recovery), 12% from mutual-help organizations, 12% from treatment and alumni groups, 24% from general study announcements in various outlets, 15% from “word of mouth”, and 24% from other sources. Participants from around the globe, with a small percentage outside the U.S., completed a comprehensive 47-item survey. This survey probed a spectrum of recovery dimensions (see figure below), allowing participants to convey whether an element “definitely belongs” in one’s definition of recovery, “somewhat belongs”, “does not belong in your definition of recovery but may belong in other people’s definition of recovery”, or “does not really belong in a definition of recovery” across domains such as abstinence, life essentials, enrichment, and spirituality. The survey utilized a technique to distill complex survey responses into core themes. This method helped reveal underlying patterns in how individuals define their own recoveries, reducing the broad array of survey items into more manageable groups of related concepts. By doing so, the researchers could identify the most central elements to recovery as consistently understood by a diverse group of participants with lived experience.

The study also examined whether endorsed elements were consistent across sociodemographic variables, substance use problem characteristics, help-seeking history, and severity of substance use disorders as defined by the DSM-5. In analyzing the data, the team defined 30 distinct subgroups based on these variables to assess the commonality and centrality of various recovery elements to establish a shared and empirically grounded framework of recovery that resonates with the broadest spectrum of individuals on their recovery journey.

Core recovery elements mapped onto both personal growth and substance use processes

The study identified core elements crucial to recovery, each endorsed by at least 80% of respondents and consistently ranked among the top 10 across 30 subgroups. These elements include Personal Growth, highlighted by 94.5% of participants, indicating a universal aspiration for personal development. Personal Integrity, comprising honesty with oneself (93.2%) and taking responsibility (92.4%), emphasizes self-reflection and accountability. Additionally, Emotional Balance was deemed crucial by 91.4% of respondents, underlining the importance of resilience in navigating life’s challenges.

Certain elements prevailed across most subgroups. Joy and Emotional Coping were endorsed by over 90% of participants, emphasizing the significance of emotional well-being in recovery. Additionally, Abstinence and Moderation were recognized by 90.1%, indicating a shift towards moderation alongside traditional abstinence approaches.

Some elements were unique to certain recovery pathways

Unique recovery definitions surfaced among subgroups with milder substance use disorder severity, non-abstinent recovery pathways, or no history of specialty treatment or mutual-help group involvement. For instance, those in non-abstinent recovery emphasized taking responsibility, suggesting a preference for self-reliance in this subgroup.

Participants receiving medication for opioid use disorder prioritized aspects of physical health, reflecting a medicalized view of substance use disorder resolution influenced by severe health consequences associated with opioid use.

Those with experience in “second wave” mutual-help organizations – sometimes called 12-step “alternatives” (e.g., SMART Recovery) emphasized enjoying life without substances (92% endorsement) and mental health care, aligning with the psychological framing of addiction treatment in such programs.

The recent study sheds light on the common elements perceived as central to recovery by individuals who have experienced alcohol and other drug problems. It analyzed responses from a national survey, defining “core” elements of recovery as those most commonly endorsed by respondents and consistent across diverse subgroups. Four key elements emerged: personal growth, personal integrity (including honesty and responsibility), and emotional balance. Furthermore, the ability to find joy and manage emotions without substances, and commitment to nonproblematic use or abstinence, were prevalent among the majority. This suggests, unsurprisingly given the study’s focus on recovery from substance use disorder, that substance use goals are important to the vast majority of those in recovery.

These findings are consistent with established recovery concepts that frame it as a dynamic process of change, involving self-improvement and improved emotional self-regulation. Notably, the study introduces honesty and responsibility as potential new dimensions for formal recovery definitions. The consensus on the importance of substance use goals, includes – but is not limited to – abstinence. Notably, central definitions also included, implicitly, developing strategies to enjoy life and handle unpleasant emotions without “using drugs or drinking like I used to”.

Divergent recovery experiences and needs were noted among subgroups with milder substance use disorder severity or those not involved in traditional treatment or support groups, emphasizing self-reliance. For those in medication-assisted recovery, physical health was a significant focus, reflecting a medical perspective on recovery. In contrast, individuals with experience in second-wave mutual-help organizations like SMART Recovery highlighted psychological health and enjoyment of life without substances, aligning potentially with a psychological understanding of addiction treatment within these programs.

This study offers a nuanced view of recovery, emphasizing it as a multifaceted process involving growth, personal integrity, and balanced reactions to life’s challenges. The most common elements of recovery across subgroups included enjoying life and handling negative emotions without substance use, while contributing positively to society.

Zemore, S. E., Ziemer, K. L., Gilbert, P. A., Karno, M. P., & Kaskutas, L. A. (2023). Understanding the shared meaning of recovery from substance use disorders: New findings from the What is Recovery? Study. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/11782218231199372

l

From a scientific perspective, recovery from substance use disorder is conceptualized not just in terms of substance use, but as a multifaceted process of ongoing personal development, aiming for sustained improvements in all areas of life. While there have been many attempts to “define” recovery, multiple pathways (e.g., abstinence vs. non-abstinence; assisted vs. unassisted etc.) and multiple settings (e.g., community vs. clinical vs. neither) suggest recovery processes are conditional on individual and contextual factors.

Rather than imposing a top-down definition of recovery, this study considered the collective voices of individuals with lived recovery experience, aiming to forge an empirical, shared understanding of the term. Through the analysis of existing data from the “What Is Recovery?” study, this research sought to identify the common ground among recovery experiences, regardless of the individual paths taken. It is an exploratory study, aiming to distill the essence of recovery by individuals with direct lived experience, and in turn, to inform and refine conceptual frameworks used by institutions and the design of substance use disorder services and research.

This was a cross-sectional survey, meaning it provides a snapshot of information about the population at that specific moment, allowing researchers to analyze relationships between variables or characteristics without the need for follow-up over time. It drew responses from 9,341 individuals recruited directly from a varied group of recovery organizations who self-identified as being “in recovery”, “recovered”, “in medication-assisted recovery”, or as “having had a problem with alcohol or drugs but [who] no longer do”.

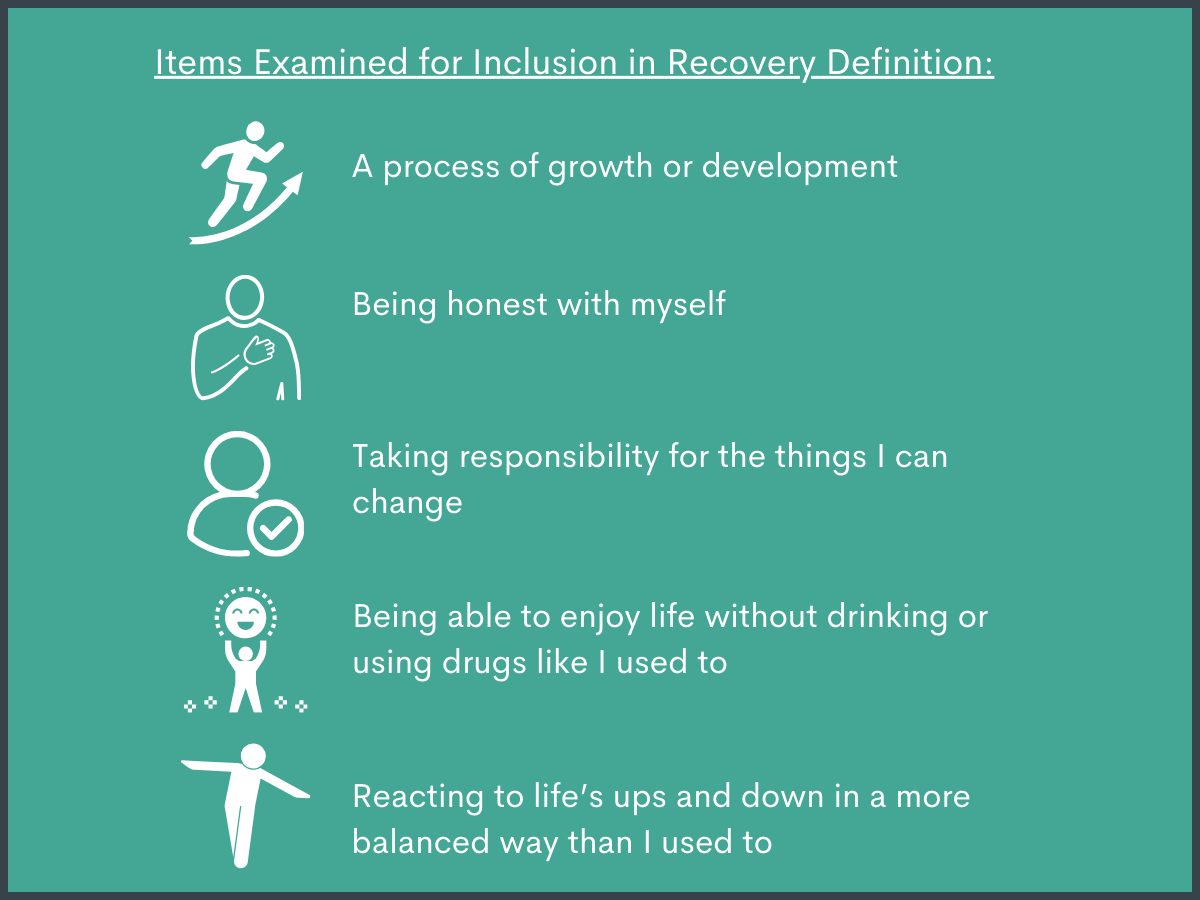

Study staff recruited participants from over 200 research partners ranging from treatment programs to recovery organizations, in addition to outreach through various media and personal networks. Among these sources, the study included 12% from recovery organizations (e.g., Faces and Voices of Recovery), 12% from mutual-help organizations, 12% from treatment and alumni groups, 24% from general study announcements in various outlets, 15% from “word of mouth”, and 24% from other sources. Participants from around the globe, with a small percentage outside the U.S., completed a comprehensive 47-item survey. This survey probed a spectrum of recovery dimensions (see figure below), allowing participants to convey whether an element “definitely belongs” in one’s definition of recovery, “somewhat belongs”, “does not belong in your definition of recovery but may belong in other people’s definition of recovery”, or “does not really belong in a definition of recovery” across domains such as abstinence, life essentials, enrichment, and spirituality. The survey utilized a technique to distill complex survey responses into core themes. This method helped reveal underlying patterns in how individuals define their own recoveries, reducing the broad array of survey items into more manageable groups of related concepts. By doing so, the researchers could identify the most central elements to recovery as consistently understood by a diverse group of participants with lived experience.

The study also examined whether endorsed elements were consistent across sociodemographic variables, substance use problem characteristics, help-seeking history, and severity of substance use disorders as defined by the DSM-5. In analyzing the data, the team defined 30 distinct subgroups based on these variables to assess the commonality and centrality of various recovery elements to establish a shared and empirically grounded framework of recovery that resonates with the broadest spectrum of individuals on their recovery journey.

Core recovery elements mapped onto both personal growth and substance use processes

The study identified core elements crucial to recovery, each endorsed by at least 80% of respondents and consistently ranked among the top 10 across 30 subgroups. These elements include Personal Growth, highlighted by 94.5% of participants, indicating a universal aspiration for personal development. Personal Integrity, comprising honesty with oneself (93.2%) and taking responsibility (92.4%), emphasizes self-reflection and accountability. Additionally, Emotional Balance was deemed crucial by 91.4% of respondents, underlining the importance of resilience in navigating life’s challenges.

Certain elements prevailed across most subgroups. Joy and Emotional Coping were endorsed by over 90% of participants, emphasizing the significance of emotional well-being in recovery. Additionally, Abstinence and Moderation were recognized by 90.1%, indicating a shift towards moderation alongside traditional abstinence approaches.

Some elements were unique to certain recovery pathways

Unique recovery definitions surfaced among subgroups with milder substance use disorder severity, non-abstinent recovery pathways, or no history of specialty treatment or mutual-help group involvement. For instance, those in non-abstinent recovery emphasized taking responsibility, suggesting a preference for self-reliance in this subgroup.

Participants receiving medication for opioid use disorder prioritized aspects of physical health, reflecting a medicalized view of substance use disorder resolution influenced by severe health consequences associated with opioid use.

Those with experience in “second wave” mutual-help organizations – sometimes called 12-step “alternatives” (e.g., SMART Recovery) emphasized enjoying life without substances (92% endorsement) and mental health care, aligning with the psychological framing of addiction treatment in such programs.

The recent study sheds light on the common elements perceived as central to recovery by individuals who have experienced alcohol and other drug problems. It analyzed responses from a national survey, defining “core” elements of recovery as those most commonly endorsed by respondents and consistent across diverse subgroups. Four key elements emerged: personal growth, personal integrity (including honesty and responsibility), and emotional balance. Furthermore, the ability to find joy and manage emotions without substances, and commitment to nonproblematic use or abstinence, were prevalent among the majority. This suggests, unsurprisingly given the study’s focus on recovery from substance use disorder, that substance use goals are important to the vast majority of those in recovery.

These findings are consistent with established recovery concepts that frame it as a dynamic process of change, involving self-improvement and improved emotional self-regulation. Notably, the study introduces honesty and responsibility as potential new dimensions for formal recovery definitions. The consensus on the importance of substance use goals, includes – but is not limited to – abstinence. Notably, central definitions also included, implicitly, developing strategies to enjoy life and handle unpleasant emotions without “using drugs or drinking like I used to”.

Divergent recovery experiences and needs were noted among subgroups with milder substance use disorder severity or those not involved in traditional treatment or support groups, emphasizing self-reliance. For those in medication-assisted recovery, physical health was a significant focus, reflecting a medical perspective on recovery. In contrast, individuals with experience in second-wave mutual-help organizations like SMART Recovery highlighted psychological health and enjoyment of life without substances, aligning potentially with a psychological understanding of addiction treatment within these programs.

This study offers a nuanced view of recovery, emphasizing it as a multifaceted process involving growth, personal integrity, and balanced reactions to life’s challenges. The most common elements of recovery across subgroups included enjoying life and handling negative emotions without substance use, while contributing positively to society.

Zemore, S. E., Ziemer, K. L., Gilbert, P. A., Karno, M. P., & Kaskutas, L. A. (2023). Understanding the shared meaning of recovery from substance use disorders: New findings from the What is Recovery? Study. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/11782218231199372

151 Merrimac St., 4th Floor. Boston, MA 02114