Brain stimulation, a neuro–surgical procedure intended to directly influence brain activity, shows promise as a new treatment. This pilot study tested its safety and preliminary efficacy for individuals with severe alcohol use disorder.

Brain stimulation, a neuro–surgical procedure intended to directly influence brain activity, shows promise as a new treatment. This pilot study tested its safety and preliminary efficacy for individuals with severe alcohol use disorder.

l

Alcohol use disorder is often chronic and relapsing and can continue to worsen, despite the fact that affected individuals suffer from serious psychological and physical consequences. While there are many helpful treatments for alcohol use disorder, not all individuals respond to first-line behavioral and pharmacological approaches. Some individuals, especially those with severe treatment resistant forms of the disorder, may require more specialized and ongoing care. Taking clues from neuroscience, new research has investigated whether electrical stimulation to brain areas implicated in addiction can help with substance use disorder recovery.

Multiple types of brain stimulation techniques have been explored in the treatment of substance use disorders. Common stimulation techniques show promise, including those that place a magnet (specifically an electromagnetic coil) on top of the head. However, targeting brain structures involved in addictive behaviors that are farther away from the scalp – deeper down inside the brain (e.g., the reward pathway) – is challenging with these techniques and may limit their overall utility. Deep brain stimulation, wherein a surgery is performed to allow stimulation to these regions at deeper levels inside the brain, can allow scientists and physicians to determine whether probing these reward-related structures benefits individuals with addiction.

Deep brain stimulation is currently used as the standard of care for certain health conditions, including Parkinson’s Disease, essential tremor, and dystonia, but remains a new area of research in the treatment of addiction. Although it is yet unclear exactly what the “stimulation” does at the cellular level that is responsible for the benefits found in these diseases, it appears to produce disruption to these pathways that results in positive health benefits. In this way, it is similar to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) which has been shown to work well in cases of severe treatment resistant depression, but it is unclear exactly how it works.

More specific information about deep brain stimulation is needed on its safety and helpfulness in substance use disorder recovery, including alcohol use disorder.

This 12-month longitudinal pilot study tested the safety and early indicators of efficacy for deep brain stimulation to the brain’s reward system as a potential treatment for severe treatment resistant alcohol use disorder.

This study included 6 adults with severe alcohol use disorder (severe defined as meeting 6 or more criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual fifth edition [DSM-5]) that were referred to the study by family physicians, psychiatrists, or hepatologists. The participants (4 males, 2 females; ages 30-66-years old) had a history of heavy alcohol use for several years (range 6-25 years). Inclusion criteria in addition to current severe alcohol use disorder (AUD), included a history of AUD for at least 2 years with evidence of repeated failure to respond to evidence-based treatments. Exclusion criteria included any past or current evidence of psychosis or mania, active neurological disease (e.g., epilepsy), and presence of clinical and/or neurological conditions that may increase the risk for the surgical procedure. This was an open-label study, meaning all participants knew that they would receive the active treatment of deep brain stimulation.

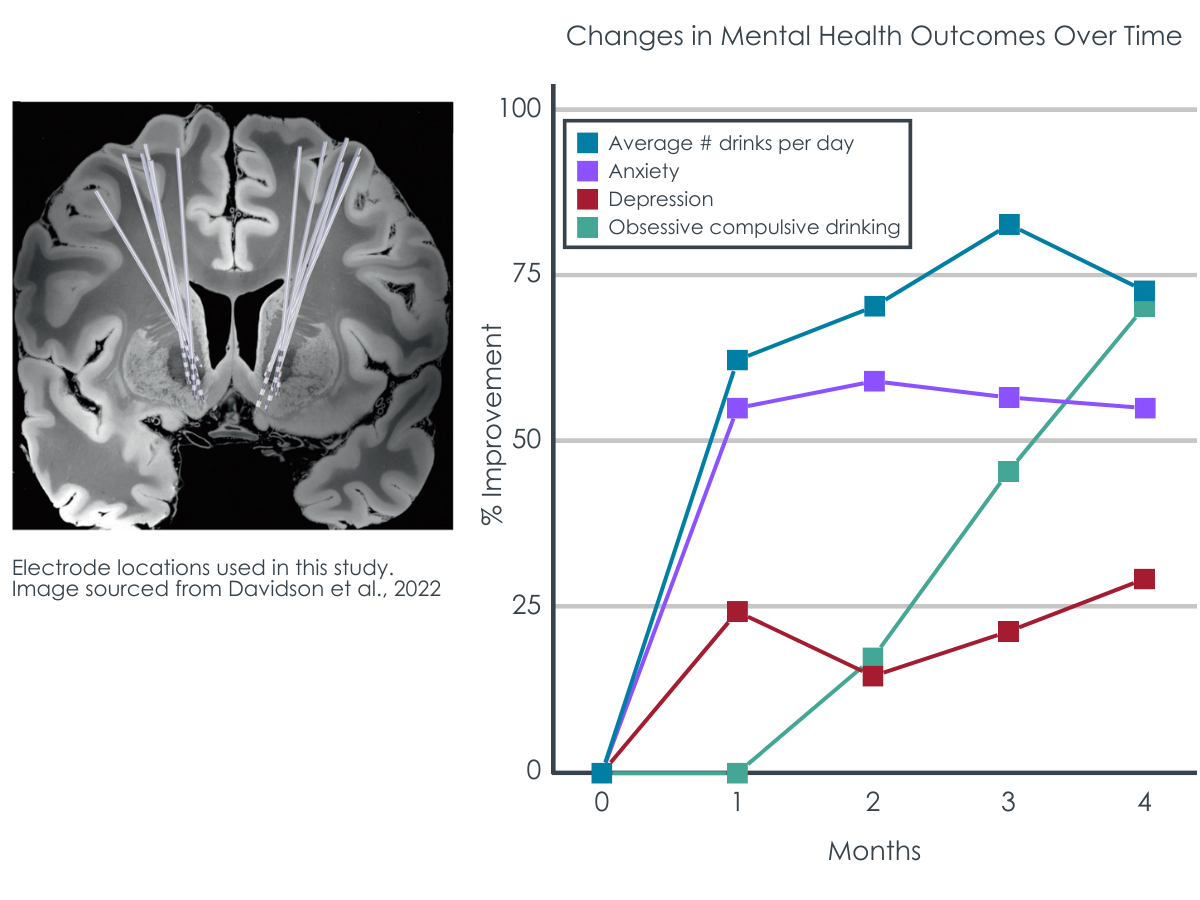

Each participant underwent a surgery to place electrodes to provide repeated electrical stimulation (titrated upwards to a clinical effect for each participant) to the nucleus accumbens, a central structure in the brain’s reward pathway. Prior to the procedure, and then biweekly for 2 months, monthly for 4 months, bimonthly for 6 months following the procedure, clinical outcome measures related to alcohol use (e.g., alcohol involvement and impairment via the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; thoughts about alcohol use via the Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking Scale; alcohol frequency via the Timeline Follow back), depression, and anxiety were administered. Brain scans measuring glucose metabolism (via positron emission tomography [PET]) in the nucleus accumbens were performed prior to the procedure and 6 months following the procedure. Glucose metabolism is considered an indirect indicator of brain activity, as glucose is metabolic fuel for brain cells (neurons), and researchers measure it to understand brain differences in health disease. Brain scans measuring the functional connections between the nucleus accumbens, and other brain regions were acquired prior to the procedure and at the final follow-up (12 months).

The two primary outcomes of this open-label pilot study, which were specified before the study (i.e., “a priori”) were the safety of the procedure and changes in self-reported alcohol consumption at 6 months compared with baseline.

The procedure was generally well tolerated.

The surgical procedure was generally well tolerated by the 6 participants. One participant developed an infection that required a follow-up procedure. Less serious side effects (i.e., adverse events) included a transient increase in irritability, argumentativeness, and risky behavior in one participant, scalp irritation in one participant, fatigue in one participant, and headaches in all 6 participants. All less serious adverse events resolved during the study.

Alcohol consumption decreased and alcohol use disorder symptoms improved.

The primary outcome of self-reported alcohol consumption decreased across the 12-month study period with moderate to large effect sizes (Figure), as did other clinical outcome measures associated with thoughts about alcohol use and alcohol use disorder symptoms. Additional clinical outcome measures, including depression and anxiety symptoms, likewise showed improvements, albeit to a smaller extent than alcohol related outcomes.

Functional brain changes consistent with recovery were observed over time.

Compared to scans taken before the procedure, decreases in glucose metabolism were observed in the nucleus accumbens (the target of deep brain stimulation) 6 months after the deep brain stimulation treatment began. Additional brain changes following deep brain stimulation were also observed, including changes in the functional connections between the nucleus accumbens and brain regions involved in visual processing.

Figure 1 adapted from Davidson et al., 2022. Deep Brain Stimulation in the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder. Left) MRI image of the placement of the electrodes that stimulated the brain’s reward pathway, targeting the nucleus accumbens. Right) percent improvement from baseline on the primary outcome of alcohol consumption (timeline follow back procedure, TLFB), as well as additional clinical outcomes of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HAMD), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI), and thoughts about alcohol use (Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking scale, OCDS).

In this open label pilot study, deep brain stimulation to the nucleus accumbens, a structure in the brain’s reward pathways, showed early signs as a potential treatment for adults with severe alcohol use disorder who have not responded to more traditional evidence-based treatments. The procedure was generally well-tolerated, with largely non serious negative effects experienced, which resolved during the study. Self-reported alcohol consumption, the primary, pre-established clinical outcome, showed moderate to large decreases over the course of the twelve-month study. Other clinical outcome measures, such as depression and anxiety, likewise showed improvements during the treatment, albeit to a smaller extent.

The exact mechanisms mediating the treatment responses to deep brain stimulation are not yet clear. This study also used brain imaging to examine metabolic and functional brain changes that might underlie the observed clinical improvements.

Decreases in glucose metabolism in the key reward structure of the brain targeted in the procedure (nucleus accumbens) were seen during deep brain stimulation treatment, which based on related prior work, may serve as a brain-based marker of recovery. Initial signs of broader changes in functional connections between the nucleus accumbens and cortical regions supporting visual processing were also seen. Again here, it is as yet unclear as to why these specific visual processing regions may be implicated in alcohol use reductions.

This initial pilot study provides promising preliminary data that can support future experimental studies (i.e., randomly assigning participants to receive this active stimulation treatment or a sham treatment) with larger samples and more comprehensive measures to better understand the clinical benefits of deep brain stimulation. While there are limitations of this study to consider (see below), as more evidence is accumulated, scientists and physicians can better determine whether deep brain stimulation can serve as a helpful and safe treatment to be integrated into clinical care for severe treatment non-responsive alcohol use disorder. Currently, however, this treatment requires more research.

Deep brain stimulation to the reward system shows some early signs as a potentially safe and helpful treatment for patients with severe and refractory alcohol use disorder. The observed therapeutic effects of stimulation to the nucleus accumbens in the brain’s reward pathway add to established research on the neuroscience of addiction that implicates these circuits in addictive behavior. However, more studies, with “sham” surgery comparison conditions and comparisons to existing and less invasive treatments, larger sample sizes and more comprehensive brain imaging protocols are necessary to ensure the validity and generalizability of the results reported here and to determine the benefits of deep brain stimulation relative to its potential risks.

Davidson, B., Giacobbe, P., George, T. P., Nestor, S. M., Rabin, J. S., Goubran, M., … & Lipsman, N. (2022). Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in the treatment of severe alcohol use disorder: a phase I pilot trial. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(10), 3992-4000. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01677-6.

l

Alcohol use disorder is often chronic and relapsing and can continue to worsen, despite the fact that affected individuals suffer from serious psychological and physical consequences. While there are many helpful treatments for alcohol use disorder, not all individuals respond to first-line behavioral and pharmacological approaches. Some individuals, especially those with severe treatment resistant forms of the disorder, may require more specialized and ongoing care. Taking clues from neuroscience, new research has investigated whether electrical stimulation to brain areas implicated in addiction can help with substance use disorder recovery.

Multiple types of brain stimulation techniques have been explored in the treatment of substance use disorders. Common stimulation techniques show promise, including those that place a magnet (specifically an electromagnetic coil) on top of the head. However, targeting brain structures involved in addictive behaviors that are farther away from the scalp – deeper down inside the brain (e.g., the reward pathway) – is challenging with these techniques and may limit their overall utility. Deep brain stimulation, wherein a surgery is performed to allow stimulation to these regions at deeper levels inside the brain, can allow scientists and physicians to determine whether probing these reward-related structures benefits individuals with addiction.

Deep brain stimulation is currently used as the standard of care for certain health conditions, including Parkinson’s Disease, essential tremor, and dystonia, but remains a new area of research in the treatment of addiction. Although it is yet unclear exactly what the “stimulation” does at the cellular level that is responsible for the benefits found in these diseases, it appears to produce disruption to these pathways that results in positive health benefits. In this way, it is similar to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) which has been shown to work well in cases of severe treatment resistant depression, but it is unclear exactly how it works.

More specific information about deep brain stimulation is needed on its safety and helpfulness in substance use disorder recovery, including alcohol use disorder.

This 12-month longitudinal pilot study tested the safety and early indicators of efficacy for deep brain stimulation to the brain’s reward system as a potential treatment for severe treatment resistant alcohol use disorder.

This study included 6 adults with severe alcohol use disorder (severe defined as meeting 6 or more criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual fifth edition [DSM-5]) that were referred to the study by family physicians, psychiatrists, or hepatologists. The participants (4 males, 2 females; ages 30-66-years old) had a history of heavy alcohol use for several years (range 6-25 years). Inclusion criteria in addition to current severe alcohol use disorder (AUD), included a history of AUD for at least 2 years with evidence of repeated failure to respond to evidence-based treatments. Exclusion criteria included any past or current evidence of psychosis or mania, active neurological disease (e.g., epilepsy), and presence of clinical and/or neurological conditions that may increase the risk for the surgical procedure. This was an open-label study, meaning all participants knew that they would receive the active treatment of deep brain stimulation.

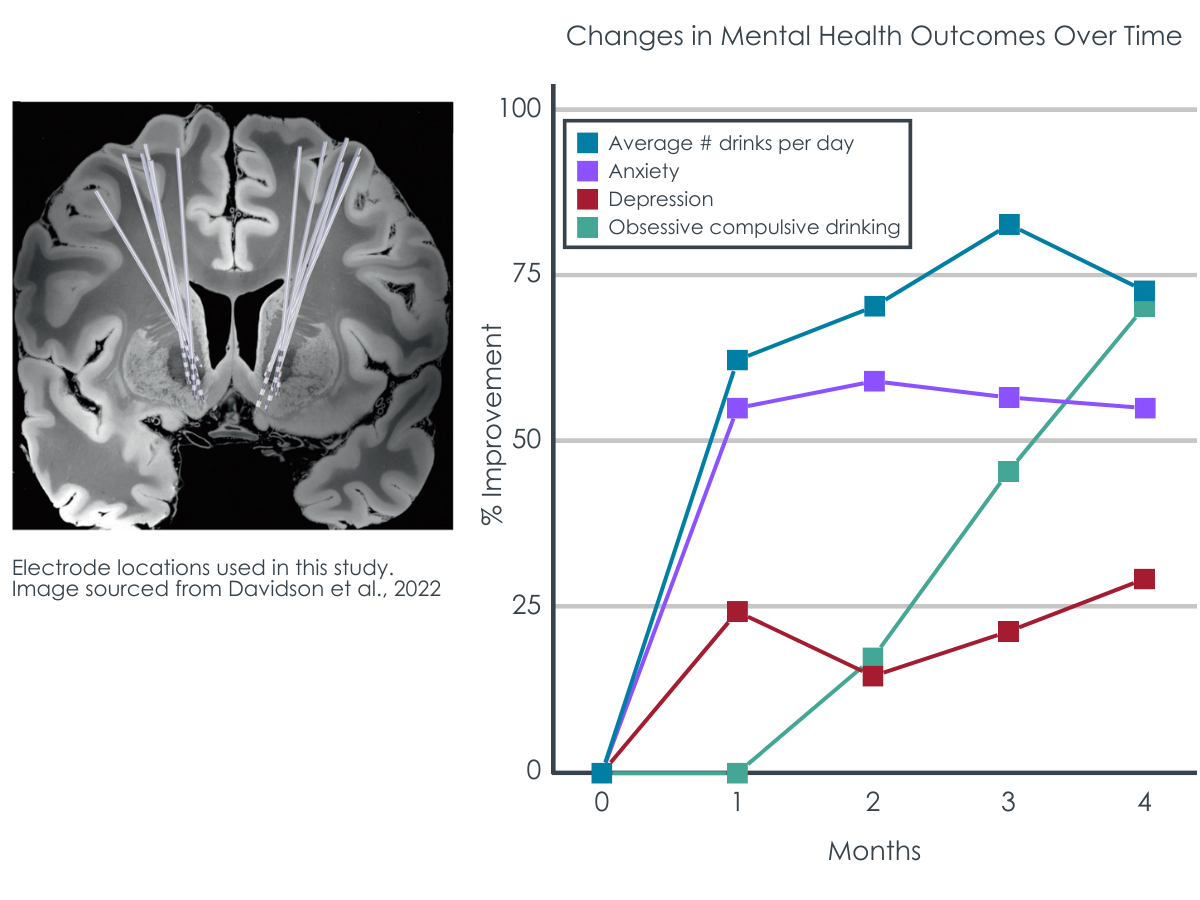

Each participant underwent a surgery to place electrodes to provide repeated electrical stimulation (titrated upwards to a clinical effect for each participant) to the nucleus accumbens, a central structure in the brain’s reward pathway. Prior to the procedure, and then biweekly for 2 months, monthly for 4 months, bimonthly for 6 months following the procedure, clinical outcome measures related to alcohol use (e.g., alcohol involvement and impairment via the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; thoughts about alcohol use via the Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking Scale; alcohol frequency via the Timeline Follow back), depression, and anxiety were administered. Brain scans measuring glucose metabolism (via positron emission tomography [PET]) in the nucleus accumbens were performed prior to the procedure and 6 months following the procedure. Glucose metabolism is considered an indirect indicator of brain activity, as glucose is metabolic fuel for brain cells (neurons), and researchers measure it to understand brain differences in health disease. Brain scans measuring the functional connections between the nucleus accumbens, and other brain regions were acquired prior to the procedure and at the final follow-up (12 months).

The two primary outcomes of this open-label pilot study, which were specified before the study (i.e., “a priori”) were the safety of the procedure and changes in self-reported alcohol consumption at 6 months compared with baseline.

The procedure was generally well tolerated.

The surgical procedure was generally well tolerated by the 6 participants. One participant developed an infection that required a follow-up procedure. Less serious side effects (i.e., adverse events) included a transient increase in irritability, argumentativeness, and risky behavior in one participant, scalp irritation in one participant, fatigue in one participant, and headaches in all 6 participants. All less serious adverse events resolved during the study.

Alcohol consumption decreased and alcohol use disorder symptoms improved.

The primary outcome of self-reported alcohol consumption decreased across the 12-month study period with moderate to large effect sizes (Figure), as did other clinical outcome measures associated with thoughts about alcohol use and alcohol use disorder symptoms. Additional clinical outcome measures, including depression and anxiety symptoms, likewise showed improvements, albeit to a smaller extent than alcohol related outcomes.

Functional brain changes consistent with recovery were observed over time.

Compared to scans taken before the procedure, decreases in glucose metabolism were observed in the nucleus accumbens (the target of deep brain stimulation) 6 months after the deep brain stimulation treatment began. Additional brain changes following deep brain stimulation were also observed, including changes in the functional connections between the nucleus accumbens and brain regions involved in visual processing.

Figure 1 adapted from Davidson et al., 2022. Deep Brain Stimulation in the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder. Left) MRI image of the placement of the electrodes that stimulated the brain’s reward pathway, targeting the nucleus accumbens. Right) percent improvement from baseline on the primary outcome of alcohol consumption (timeline follow back procedure, TLFB), as well as additional clinical outcomes of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HAMD), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI), and thoughts about alcohol use (Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking scale, OCDS).

In this open label pilot study, deep brain stimulation to the nucleus accumbens, a structure in the brain’s reward pathways, showed early signs as a potential treatment for adults with severe alcohol use disorder who have not responded to more traditional evidence-based treatments. The procedure was generally well-tolerated, with largely non serious negative effects experienced, which resolved during the study. Self-reported alcohol consumption, the primary, pre-established clinical outcome, showed moderate to large decreases over the course of the twelve-month study. Other clinical outcome measures, such as depression and anxiety, likewise showed improvements during the treatment, albeit to a smaller extent.

The exact mechanisms mediating the treatment responses to deep brain stimulation are not yet clear. This study also used brain imaging to examine metabolic and functional brain changes that might underlie the observed clinical improvements.

Decreases in glucose metabolism in the key reward structure of the brain targeted in the procedure (nucleus accumbens) were seen during deep brain stimulation treatment, which based on related prior work, may serve as a brain-based marker of recovery. Initial signs of broader changes in functional connections between the nucleus accumbens and cortical regions supporting visual processing were also seen. Again here, it is as yet unclear as to why these specific visual processing regions may be implicated in alcohol use reductions.

This initial pilot study provides promising preliminary data that can support future experimental studies (i.e., randomly assigning participants to receive this active stimulation treatment or a sham treatment) with larger samples and more comprehensive measures to better understand the clinical benefits of deep brain stimulation. While there are limitations of this study to consider (see below), as more evidence is accumulated, scientists and physicians can better determine whether deep brain stimulation can serve as a helpful and safe treatment to be integrated into clinical care for severe treatment non-responsive alcohol use disorder. Currently, however, this treatment requires more research.

Deep brain stimulation to the reward system shows some early signs as a potentially safe and helpful treatment for patients with severe and refractory alcohol use disorder. The observed therapeutic effects of stimulation to the nucleus accumbens in the brain’s reward pathway add to established research on the neuroscience of addiction that implicates these circuits in addictive behavior. However, more studies, with “sham” surgery comparison conditions and comparisons to existing and less invasive treatments, larger sample sizes and more comprehensive brain imaging protocols are necessary to ensure the validity and generalizability of the results reported here and to determine the benefits of deep brain stimulation relative to its potential risks.

Davidson, B., Giacobbe, P., George, T. P., Nestor, S. M., Rabin, J. S., Goubran, M., … & Lipsman, N. (2022). Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in the treatment of severe alcohol use disorder: a phase I pilot trial. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(10), 3992-4000. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01677-6.

l

Alcohol use disorder is often chronic and relapsing and can continue to worsen, despite the fact that affected individuals suffer from serious psychological and physical consequences. While there are many helpful treatments for alcohol use disorder, not all individuals respond to first-line behavioral and pharmacological approaches. Some individuals, especially those with severe treatment resistant forms of the disorder, may require more specialized and ongoing care. Taking clues from neuroscience, new research has investigated whether electrical stimulation to brain areas implicated in addiction can help with substance use disorder recovery.

Multiple types of brain stimulation techniques have been explored in the treatment of substance use disorders. Common stimulation techniques show promise, including those that place a magnet (specifically an electromagnetic coil) on top of the head. However, targeting brain structures involved in addictive behaviors that are farther away from the scalp – deeper down inside the brain (e.g., the reward pathway) – is challenging with these techniques and may limit their overall utility. Deep brain stimulation, wherein a surgery is performed to allow stimulation to these regions at deeper levels inside the brain, can allow scientists and physicians to determine whether probing these reward-related structures benefits individuals with addiction.

Deep brain stimulation is currently used as the standard of care for certain health conditions, including Parkinson’s Disease, essential tremor, and dystonia, but remains a new area of research in the treatment of addiction. Although it is yet unclear exactly what the “stimulation” does at the cellular level that is responsible for the benefits found in these diseases, it appears to produce disruption to these pathways that results in positive health benefits. In this way, it is similar to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) which has been shown to work well in cases of severe treatment resistant depression, but it is unclear exactly how it works.

More specific information about deep brain stimulation is needed on its safety and helpfulness in substance use disorder recovery, including alcohol use disorder.

This 12-month longitudinal pilot study tested the safety and early indicators of efficacy for deep brain stimulation to the brain’s reward system as a potential treatment for severe treatment resistant alcohol use disorder.

This study included 6 adults with severe alcohol use disorder (severe defined as meeting 6 or more criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual fifth edition [DSM-5]) that were referred to the study by family physicians, psychiatrists, or hepatologists. The participants (4 males, 2 females; ages 30-66-years old) had a history of heavy alcohol use for several years (range 6-25 years). Inclusion criteria in addition to current severe alcohol use disorder (AUD), included a history of AUD for at least 2 years with evidence of repeated failure to respond to evidence-based treatments. Exclusion criteria included any past or current evidence of psychosis or mania, active neurological disease (e.g., epilepsy), and presence of clinical and/or neurological conditions that may increase the risk for the surgical procedure. This was an open-label study, meaning all participants knew that they would receive the active treatment of deep brain stimulation.

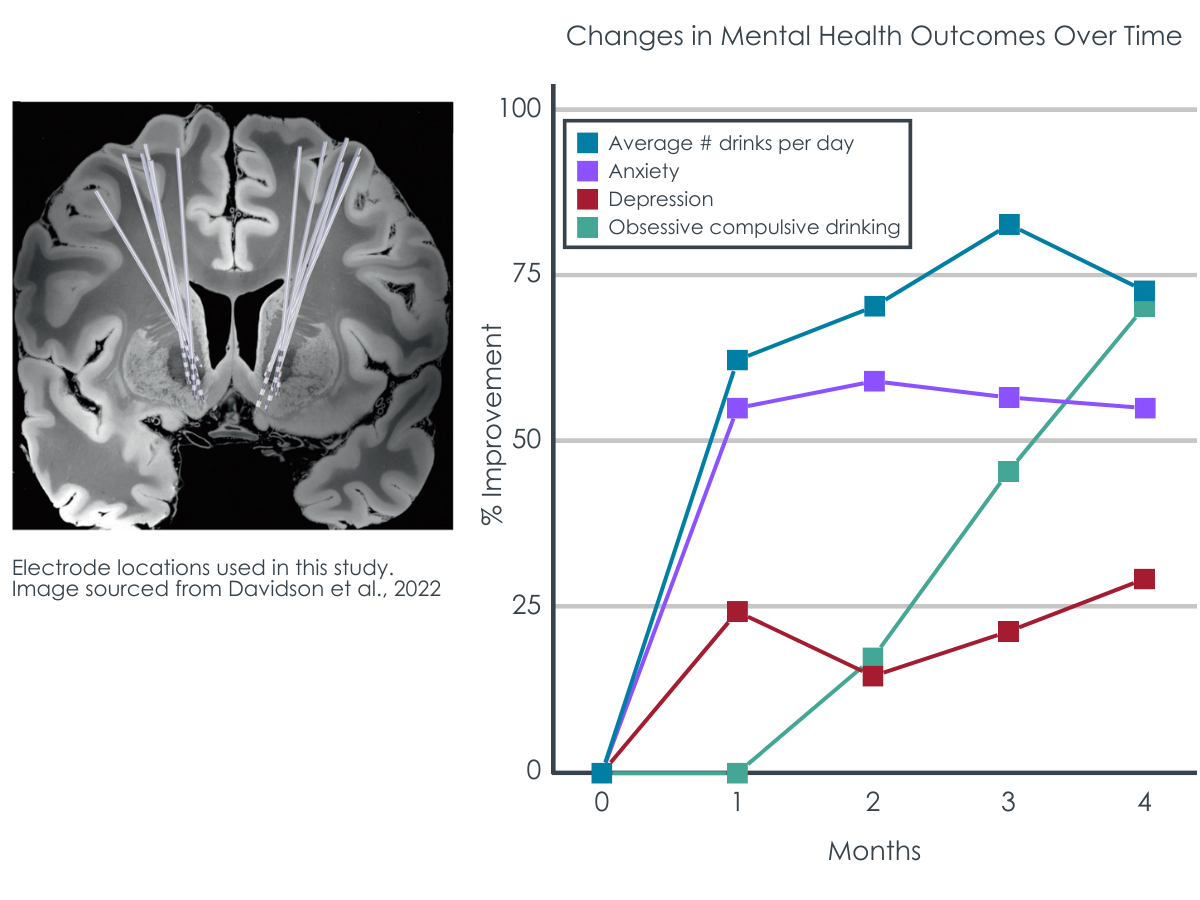

Each participant underwent a surgery to place electrodes to provide repeated electrical stimulation (titrated upwards to a clinical effect for each participant) to the nucleus accumbens, a central structure in the brain’s reward pathway. Prior to the procedure, and then biweekly for 2 months, monthly for 4 months, bimonthly for 6 months following the procedure, clinical outcome measures related to alcohol use (e.g., alcohol involvement and impairment via the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; thoughts about alcohol use via the Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking Scale; alcohol frequency via the Timeline Follow back), depression, and anxiety were administered. Brain scans measuring glucose metabolism (via positron emission tomography [PET]) in the nucleus accumbens were performed prior to the procedure and 6 months following the procedure. Glucose metabolism is considered an indirect indicator of brain activity, as glucose is metabolic fuel for brain cells (neurons), and researchers measure it to understand brain differences in health disease. Brain scans measuring the functional connections between the nucleus accumbens, and other brain regions were acquired prior to the procedure and at the final follow-up (12 months).

The two primary outcomes of this open-label pilot study, which were specified before the study (i.e., “a priori”) were the safety of the procedure and changes in self-reported alcohol consumption at 6 months compared with baseline.

The procedure was generally well tolerated.

The surgical procedure was generally well tolerated by the 6 participants. One participant developed an infection that required a follow-up procedure. Less serious side effects (i.e., adverse events) included a transient increase in irritability, argumentativeness, and risky behavior in one participant, scalp irritation in one participant, fatigue in one participant, and headaches in all 6 participants. All less serious adverse events resolved during the study.

Alcohol consumption decreased and alcohol use disorder symptoms improved.

The primary outcome of self-reported alcohol consumption decreased across the 12-month study period with moderate to large effect sizes (Figure), as did other clinical outcome measures associated with thoughts about alcohol use and alcohol use disorder symptoms. Additional clinical outcome measures, including depression and anxiety symptoms, likewise showed improvements, albeit to a smaller extent than alcohol related outcomes.

Functional brain changes consistent with recovery were observed over time.

Compared to scans taken before the procedure, decreases in glucose metabolism were observed in the nucleus accumbens (the target of deep brain stimulation) 6 months after the deep brain stimulation treatment began. Additional brain changes following deep brain stimulation were also observed, including changes in the functional connections between the nucleus accumbens and brain regions involved in visual processing.

Figure 1 adapted from Davidson et al., 2022. Deep Brain Stimulation in the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder. Left) MRI image of the placement of the electrodes that stimulated the brain’s reward pathway, targeting the nucleus accumbens. Right) percent improvement from baseline on the primary outcome of alcohol consumption (timeline follow back procedure, TLFB), as well as additional clinical outcomes of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HAMD), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI), and thoughts about alcohol use (Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking scale, OCDS).

In this open label pilot study, deep brain stimulation to the nucleus accumbens, a structure in the brain’s reward pathways, showed early signs as a potential treatment for adults with severe alcohol use disorder who have not responded to more traditional evidence-based treatments. The procedure was generally well-tolerated, with largely non serious negative effects experienced, which resolved during the study. Self-reported alcohol consumption, the primary, pre-established clinical outcome, showed moderate to large decreases over the course of the twelve-month study. Other clinical outcome measures, such as depression and anxiety, likewise showed improvements during the treatment, albeit to a smaller extent.

The exact mechanisms mediating the treatment responses to deep brain stimulation are not yet clear. This study also used brain imaging to examine metabolic and functional brain changes that might underlie the observed clinical improvements.

Decreases in glucose metabolism in the key reward structure of the brain targeted in the procedure (nucleus accumbens) were seen during deep brain stimulation treatment, which based on related prior work, may serve as a brain-based marker of recovery. Initial signs of broader changes in functional connections between the nucleus accumbens and cortical regions supporting visual processing were also seen. Again here, it is as yet unclear as to why these specific visual processing regions may be implicated in alcohol use reductions.

This initial pilot study provides promising preliminary data that can support future experimental studies (i.e., randomly assigning participants to receive this active stimulation treatment or a sham treatment) with larger samples and more comprehensive measures to better understand the clinical benefits of deep brain stimulation. While there are limitations of this study to consider (see below), as more evidence is accumulated, scientists and physicians can better determine whether deep brain stimulation can serve as a helpful and safe treatment to be integrated into clinical care for severe treatment non-responsive alcohol use disorder. Currently, however, this treatment requires more research.

Deep brain stimulation to the reward system shows some early signs as a potentially safe and helpful treatment for patients with severe and refractory alcohol use disorder. The observed therapeutic effects of stimulation to the nucleus accumbens in the brain’s reward pathway add to established research on the neuroscience of addiction that implicates these circuits in addictive behavior. However, more studies, with “sham” surgery comparison conditions and comparisons to existing and less invasive treatments, larger sample sizes and more comprehensive brain imaging protocols are necessary to ensure the validity and generalizability of the results reported here and to determine the benefits of deep brain stimulation relative to its potential risks.

Davidson, B., Giacobbe, P., George, T. P., Nestor, S. M., Rabin, J. S., Goubran, M., … & Lipsman, N. (2022). Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in the treatment of severe alcohol use disorder: a phase I pilot trial. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(10), 3992-4000. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01677-6.