Describing addiction as a “chronically relapsing brain disease” is intended to decrease stigma, but may actually increase it

Biomedical terminology has been deployed purposely to describe addiction in an effort to reduce stigma. However, using these terms may have unintended consequences. While intensely debated, there were no rigorous scientific studies to empirically inform practice and policy regarding which specific terms may be most helpful in reducing stigma. In this study, the researchers used a rigorous study design to examine if exposure to a variety of commonly used medical and nonmedical terms describing opioid-related impairment makes a difference in people’s attitudes toward those with opioid use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Opioid overdoses continue to rise in the United States and most individuals with opioid use disorder do not receive any type of treatment. Part of this treatment gap may be explained by the stigmatization of opioid addiction, which may be delaying and preventing people from seeking treatment. In fact, substance use disorders, of which opioid use disorder is one type, are among the most stigmatized conditions in the world, and words used to describe this condition have been shown to affect the level of perceived stigma by healthcare professionals and the general public. For example, among the general public and mental health clinicians, exposure to the term ‘substance abuser’ tends to elicit a more punitive attitude whereas the term ‘substance use disorder’ tends to elicit a more treatment-oriented attitude.

Over the last several decades, medical terminology to describe addiction has been promoted in an effort to reduce stigma. However, some argue that this medicalization of addiction has unintended consequences, such as negatively impacting the public’s perception that people with addictions can actually change and recover, as well as reducing the sufferer’s own confidence in their ability to change. In this study, the researchers from the Recovery Research Institute* used a rigorous experimental research design and a nationally representative sample of adults from the United States general population to examine the impact of exposure to a variety of commonly used medical and nonmedical terms describing opioid-related impairment on perceptions of several dimensions of stigma, treatment need, and belief that a person suffering from opioid-related impairment could get better (i.e., prognostic optimism). The study sought to inform practice and policy communication efforts regarding which terms may be optimal in describing individuals with opioid use disorder and under what circumstances these terms might be best utilized to reduce stigma and maximize help-seeking.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a nationally representative study of adults from the United States general population where more than 3500 participants were randomized to read one of 12 descriptive vignettes using 6 commonly used terms and different genders to describe someone with opioid-related impairment. Participants were then asked to answer a series of questions that assessed attitudes across multiple dimensions of stigma and perceptions on likelihood of recovery.

The study had three main aims: to examine if exposure to commonly used medical and nonmedical terms describing opioid-related impairment produced attitudinal differences related to stigma in the general population, if these attitudes were different when the person with opioid-related impairment was portrayed as a man or a woman, and to further examine whether there were differences between men and women in how they reacted to the different ways of describing someone with opioid-related impairment.

This was a cross-sectional survey completed in February 2020. Study participants were recruited using an internationally recognized survey company that uses a population-based probability sampling approach representing 97% of all U.S. households to generate a nationally representative sample of adults aged 18 and over in the United States. Of the 5998 participants who were sampled, 3635 completed the survey for a response rate of 61%. After data were collected, they were adjusted to account for differential survey non-response to ensure that conclusions remained generalizable to the U.S. general population.

Figure 1.

Study participants were randomized to read one of 12 vignettes describing a person with opioid-related impairment who was currently receiving treatment. Six common terms were used to describe the opioid-related impairment: ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’, ‘brain disease’, ‘disease’, ‘illness’, ‘disorder’, and ‘problem’. Vignettes also depicted the person as a man a woman and used the same gender-neutral name (“Alex”). There were approximately 300 people in each randomized cell, meaning that a large number of individuals were exposed to each one of the twelve vignettes.

Figure 2.

After reading the vignette, participants were asked to answer 27 stigma-related questions representing five subscales: blame attribution, social exclusion, perceived danger, prognostic optimism, and need for continuing care. For each question, response options ranged from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ on a 1-6 scale (known as a Likert scale).

Figure 3.

The sample included 3,635 adults. On average, participants were 47.8 years of age and just over half were female (52.4%), almost two-thirds were non-Hispanic white (63.1%), employed (59.6%), had some college education (61.0%), reported income > than $50,000 (68.3%), and just over half were married (54.9%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Use of ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’ was associated with both benefits and drawbacks.

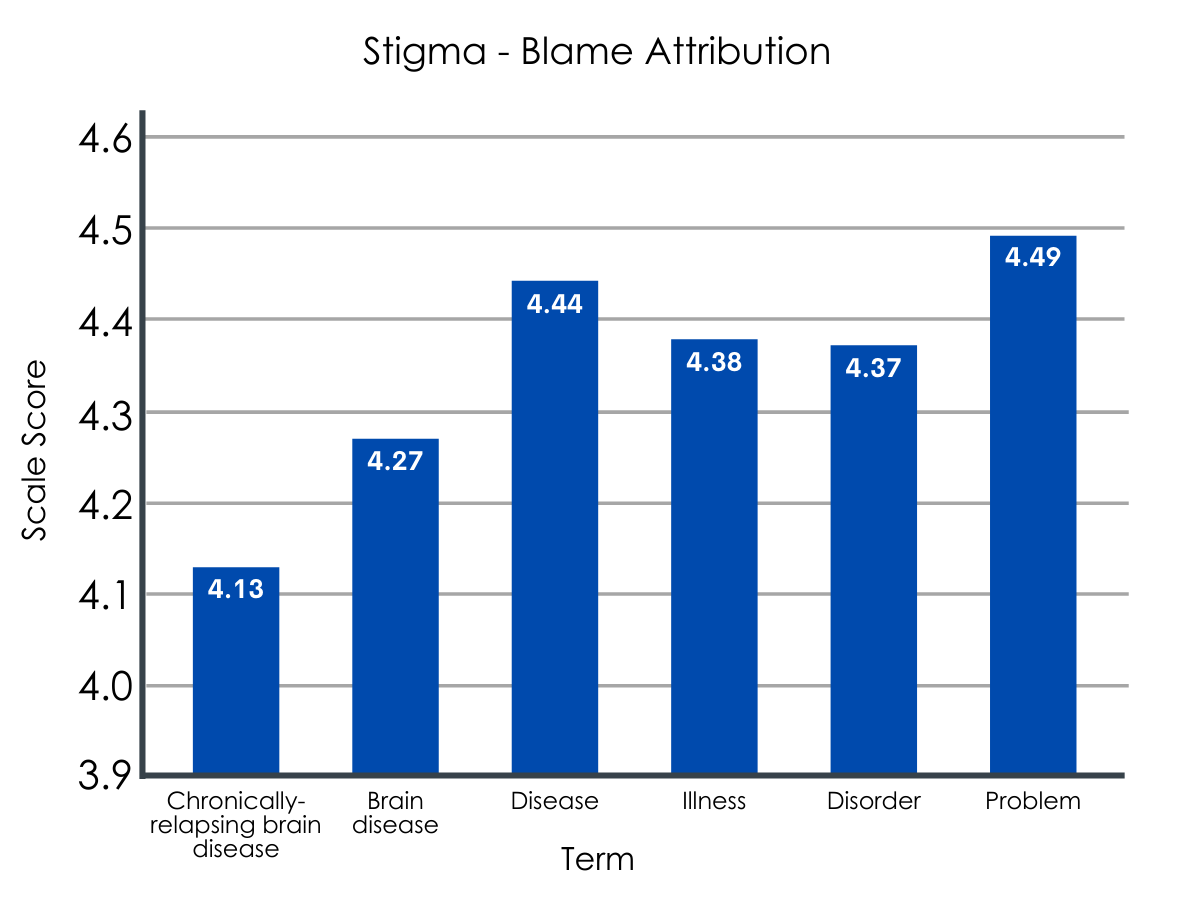

Compared with ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’, participants that were presented with any of the five other ways of describing someone with opioid-related impairment rated the person as significantly more personally to blame for their opioid impairment. Specifically, the highest blame attribution was from ‘problem’ and ‘disease’, moderate blame attribution was from ‘illness’ and ‘disorder’, and lowest blame attribution was from ‘brain disease’ and ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’.

Figure 4.

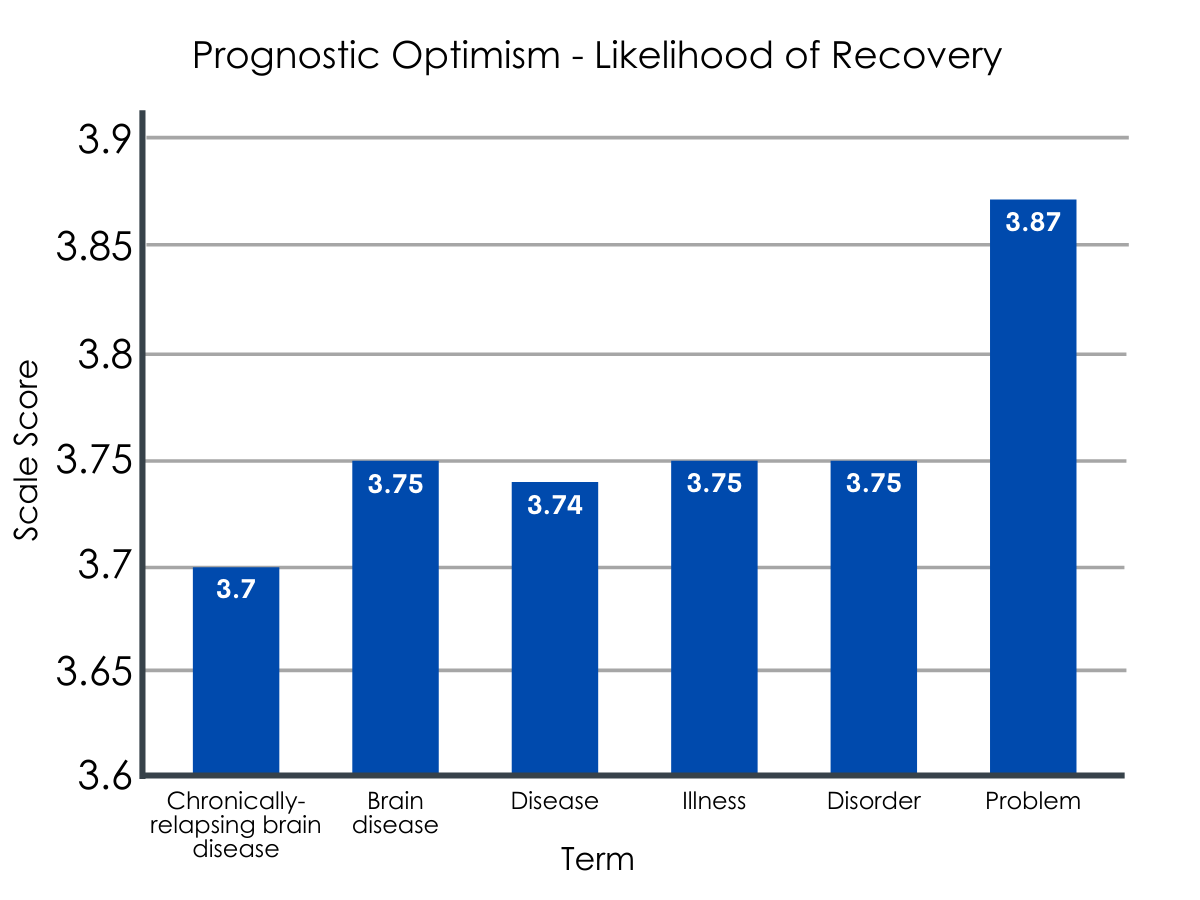

At the same time, compared with the term ‘opioid problem’, participants presented with the term ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’ rated the opioid-impaired person as being less likely to recover (decreased prognostic optimism) and as being more dangerous and having an increased need for continuing care.

Figure 5.

Gender Differences: Men were assigned less to blame for their opioid impairment but in other ways were more stigmatized.

Generally, participants attributed less blame when “Alex” was depicted as a man but simultaneously were more likely to want more social distance from a man and viewed a man as more dangerousness. When looking at the effect of gender by terminology, decreased blame attribution toward males was only observed with the term ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’. Of note, the greater prognostic optimism associated with the term ‘problem’ compared with ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’ was present regardless of whether the vignette subject was described as a man or a woman.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The study found that using the term ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’ to describe a person with opioid-related impairment produced the lowest blame attribution, with this effect more pronounced in men. However, using this exact same term also decreased the perceived likelihood that this person could recover and increased perceptions that the person was dangerous and should be socially excluded.

Study findings suggest that there is no single term to describe opioid-related impairment that can reduce all potential stigma biases. In other words, while some terms were very good at reducing certain types of stigma, these same terms increased other types of stigma, and vice versa. This indicates there may be tradeoffs to using different types of terminology to describe opioid-related impairment, and choice of terminology should be tailored according to the purpose of the communication.

Figure 6.

Message framing using language is an important strategy for garnering public support for criminal justice reform and evidence-based public health interventions with less consensus, as well as increasing the perceived agency of individuals with substance use disorders. Research at the intersection of language and stigma in the addiction and recovery field is constantly evolving, and current evidence, along with the findings of this study, suggests that there are tradeoffs when framing addiction and its consequences. Therefore, using different terminologies can be advantageous based on the context. Consistent with this study’s findings, to reduce personal shame and blame that may inhibit treatment seeking, use of more medical terminology may be optimal (e.g., ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’); whereas, if you want to increase confidence that the person can recover and is not dangerous, use of non-medical terminology may be best (e.g., ‘opioid problem’).

We do know through empirical studies that the language we use is important in describing highly stigmatized conditions like substance use disorders. Original experimental research from the RRI has shown that, among the general population and specifically among mental health clinicians, using the term ‘substance abuser’ compared with the person-first term ‘person with a substance use disorder’ increases stigma. Other research has shown that implicit bias also exists between these two terms. Language plays an important role in framing how society thinks about substance use and recovery. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary®.

However, in general, stigma is complex, consists of many levels, and can manifest itself in many ways. We are still learning about the many dimensions of the stigma construct as it relates to addiction. The current study tried to examine this complexity using a multitude of stigma dimensions measuring blame attribution, social exclusion, perceived dangerousness, and prognostic optimism, with findings suggestive that there is no straightforward way to reduce all forms of stigma.

Increasing this complexity, the settings where the language is used is likely to impact stigma. For example, mutual aid meetings such as Alcoholics Anonymous, have a long history of using terms that have been empirically found to increase stigma among behavioral health professionals, medical professionals, and the general public. This does not necessarily mean that language should be changed among recovery subcultures, but that stakeholders should be cognizant of the language they use and the settings where the language is used, as this can ultimately prevent or delay individuals with substance use disorder from seeking treatment.

The study also found a gender effect among the terminologies used, with participants attributing less blame to men while also reporting a desire for greater social distance and higher levels of perceived dangerousness. These findings suggest that, while females appear to be judged more harshly for having opioid impairment, men may have a more difficult time being accepted and reintegrated back into society after treatment.

Two important limitations must be considered in how these study findings might translate to real-world settings. First, it is unclear how these attitudinal differences resulting from exposure to different terminologies to describe a person with opioid-related impairment would lead to actionable differences, such as support for a particular policy. Second, the observed differences, though statistically significant, were small in absolute magnitude drawing into question how this small difference would translate into a real-world difference. These limitations highlight the key next steps in stigma research in the substance use disorder field.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The vignette describes a person with opioid-related impairment. It is not clear how these findings would generalize to other substances.

- Observed differences in the stigma subscales were small and it is not known how these attitudinal differences would translate into real-world actionable differences, such as support for a particular policy.

- The stigma subscales used in this study while internally consistent have not been previously validated.

- Generalizing these findings beyond a U.S. English-speaking cultural context should be done with caution.

BOTTOM LINE

The study found that using the term ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’ to describe a person suffering from opioid-related impairment was associated with the lowest blame attribution, with this effect more pronounced in men. However, using this term also decreased the general public’s perception that the person could recover and also increased perceived dangerousness, suggesting that there may not be one single term that can be used to meet all desired public health and clinical goals when attempting to reduce stigma. To reduce personal shame and blame that may inhibit treatment seeking, use of more medical terminology may be optimal (e.g., ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’); in contrast, to increase confidence that someone with opioid-related impairment can recover and is not dangerous, use of non-medical terminology may be best (e.g., ‘opioid problem’).

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Stigma is complex, consists of many facets, and can manifest itself in many ways. The words that family and friends use and the settings that they use them in matters and can influence what the general public views as potentially effective drug policies and how individuals with an opioid use disorder feel they are perceived and supported. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see RRI’s Addictionary®.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Stigma is complex, consists of many levels, and can manifest itself in many ways. Terminology to reduce stigma in the addiction and recovery field is constantly evolving. Using stigmatizing words can prevent or delay individuals with substance use disorders from seeking treatment and, more broadly, from evidence-based public health interventions being supported by the general public. Findings from this study suggest that tailoring terminology based on the purpose of communication may be warranted. For example, if the purpose is to decrease stigmatizing blame, use of more medical terminology may be optimal (e.g., ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’); in contrast, if the purpose is to increase confidence that the person can recover and is not dangerous, use of non-medical terminology may be best (e.g., ‘opioid problem’). For more information on destigmatizing language, please see RRI’s Addictionary®.

- For scientists: Terminology in the addiction and recovery field is constantly evolving and is ripe for impactful empirical studies. Although this study used a rigorous design, there were modest effect sizes and it is not clear how differences in these stigma subscales would translate to real-world differences among the general public, such as support for punitive or therapeutic policies. Future research could explore these real-world differences (e.g., answer questions about support for policies after reading the vignette used in this study), examine the effect of different terminologies outside of a U.S. English-speaking cultural context, and assess for attitudinal differences that are moderated by the respondent’s characteristics (e.g., political affiliation). In addition, the stigma subscales used in this study have not been previously validated, so future research on their construct validity is warranted. Another fruitful area of research may be how internalizing different terminologies may impact the prognosis and outcomes for individuals with substance use disorders.

- For policy makers: Stigma is complex, consists of many facets, and can manifest itself in many ways. Terminology to reduce stigma in the addiction and recovery field is constantly evolving as researchers better understand the intersection of language and stigma. Findings from this study suggest that tailoring terminology based on the purpose of the communication may be warranted. For example, if the purpose is to decrease stigmatizing blame, use of more medical terminology may be optimal (e.g., ‘chronically relapsing brain disease’); in contrast, if the purpose is to increase confidence that the person can recover and is not dangerous, use of non-medical terminology may be best (e.g., ‘opioid problem’). Choice of terminology may have an impact on evidence-based public health interventions being supported by the general public.

CITATIONS

Kelly, J.F., Greene, M.C., Abry, A. (2020). A US national randomized study to guide how best to reduce stigma when describing drug-related impairment in practice and policy. Addiction, [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1111/add.15333

*Research was conducted by RRI personnel but reviewed independently for this Bulletin