Did Insurance Payments Increase For Mental Health But Not For Substance Use Disorders?

Many economic and health care policy changes have gone into effect since 2009 that shape insurance payments for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders.

Learn more about: Addiction Treatment InsuranceSo are the insurance companies finally paying the same for mental health disorder as substance use disorder?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Millions of dollars are spent on mental health and substance use disorders every year. Economic data on trends in behavioral health treatment can inform policies designed to improve behavioral health delivery, financing, and outcomes.

However, the most recent report on historical data cover the period of 1986-2009 and many economic and healthcare policy changes have occurred since then including those related to the 2007–09 recession, the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008, and the Affordable Care Act.

Many of these policies were designed to prevent insurance companies from providing benefit limitations on mental health and substance use services.

This study fills the knowledge gap between 2009-2014 and provides an empirical basis for future decision making on mental health and substance use disorder treatments.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study analyzed multiple national databases to obtain estimates for spending on mental health and substance use disorders, percent of the population utilizing mental health and substance use disorder treatment, and prescription fills for substance use disorder. Spending estimates were calculated by identifying primary diagnosis from the International Classification of diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (IDC-9-CM) in the following six databases: SAMHSA Behavioral Health Expenditure and Use Accounts, National Health Expenditure Accounts, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, Nationwide Inpatient Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), and Economic Census Service Annual Survey.

To understand drivers of the trends in behavioral health spending (e.g., such as the percent of the population utilizing treatment) they used the SAMHSA National Survey on Drug Use and Health as their primary dataset and incorporated the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), and Nationwide Inpatient Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). In order to estimate the number of prescription fill medications used to treat substance use disorder, they analyzed data from the National Prescription Audit of the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

In 2014, spending on behavioral health treatment totaled $220 billion.

Mental health treatment spending accounted for 6.4 % of all health spending, and substance use disorder treatment spending accounted for 1.2 %.

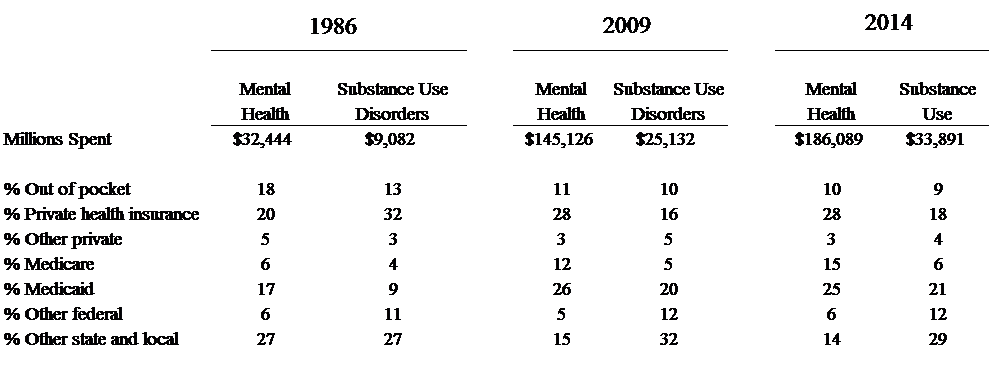

For mental health, an important trend in financing (e.g., source of payment) is the shift from a system in which the majority of funding came from state and local governments or individuals’ out-of-pocket spending (with some limited federal block grant financing) to a system that is financed largely by Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance.

The shift to insurance-based financing of treatment has been slower for substance use disorders than for mental health. Specifically, mental health spending from insurance (i.e., Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance) increased from 44% in 1986 to 68% in 2014. In contrast, substance use disorder spending from insurance was 45% in 1986 and 46% in 2014.

Noted, is the overall millions spent every year on mental health and substance use disorders has increased from 1986-2014, however, insurances have not increased their proportion of financing for substance use disorders (private health insurance actually decreased) similar to mental health.

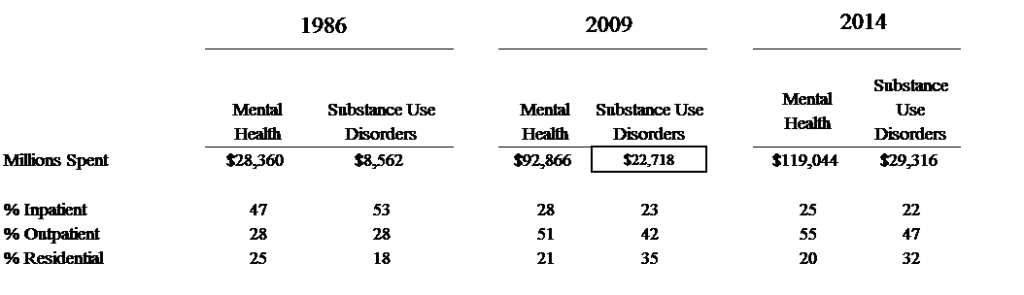

The authors also reported on the distribution of spending by inpatient, outpatient, & residential settings.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT?

This study highlights the differences in funding sources for mental health treatment versus substance use disorders. Funding for the treatment of substance use disorders has not shifted into an insurance-based system to the same degree as mental health treatment.

The authors speculate two reasons for the findings:

- medications to treat substance use disorders have lagged behind medications to treatment mental health disorders in terms of development and use

- discrimination against people with substance use disorders appear to have remained more robust than stigma associated with mental health disorders.

These negative perceptions limit individuals’ willingness to seek treatment, public support for investment, & insurance coverage for substance use disorder treatment programs.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Aggregate national data on health spending is informative. However, whether increased (or decreased) spending is a result of higher prices or greater utilization of treatment cannot be inferred. Although trends in funding sources can be documented from this data, drivers of the trends cannot be determined.

- Additionally, this information does not indicate whether spending on health is leading to better health outcomes.

NEXT STEPS

As explained by the authors, a report on health account spending should be used to help determine how spending on care for mental health or substance use disorder treatments, and utilization, relate to population health. Future research should seek to integrate all these elements, at this time, a cohesive database of this nature does not exist.

BOTTOM LINE

- For Individuals & families seeking recovery: This is macroeconomic data presented in aggregate form which does not lend itself to providing specific recommendations on an individual level. Ultimately this study showed that insurance payments increased for mental health conditions but not for substance use disorders from 1986-2014. However, if this trend has an impact on treatment or recovery outcomes cannot be determined.

- For Scientists: This study has found that spending increased a great deal from 1986-2014 on mental health and substance use disorder treatments. However, it is unknown if the health of the population has improved as a result. More research is needed to identify and track population level indicators of health. In addition, further investigation is needed to understand why private health insurance funding for substance use disorders has for the most part decreased since 1986 but increased for mental health treatment.

- For Policy makers: Since 1986 substance use disorder treatments have not shifted to an insurance-based system similar to mental health treatment. Substance use disorder treatment is more reliant on state and local governments for funding (e.g., taxpayer dollars) compared to mental health. Higher priority is needed for research to address the role that insurance companies have in paying for substance use disorder treatment.

- For Treatment professionals and treatment systems: From 2004-2013 there was a growth in the percentage of adults who received mental health and substance use disorder treatment explained by an increased use of medications. This study suggests that medication based treatments are becoming more common while use of psychosocial treatments is either staying the same or perhaps becoming less common.

CITATIONS

Mark, T. L., Yee, T., Levit, K. R., Camacho-Cook, J., Cutler, E., Carroll, C. D. (2016). Insurance financing increased for mental health conditions but not for substance use disorders, 1986-2014. Health Affairs, 35(6), 958-965.