Does Alcohol Policy Enforcement Decrease Harmful Drinking?

Alcohol use disorders and other forms of harmful drinking are major contributors to disease, disability, and premature death and cost the United States about $250 billion each year in health care costs, lost productivity, and crime.

It is important to discover, develop, and implement ways to reduce the negative impact of alcohol use on society.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In the current study, Erickson and colleagues analyzed whether living in a state with stronger alcohol policies and/or stronger enforcement of those policies by police was related to lower likelihood of harmful drinking.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

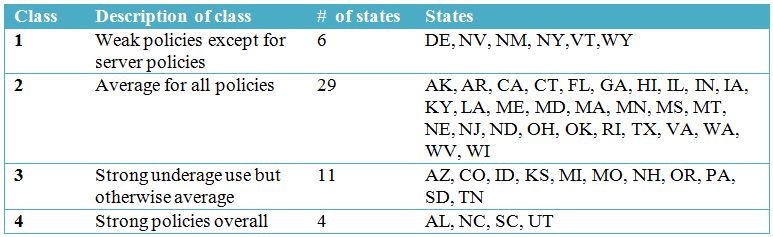

In this study, researchers used a statistical procedure called latent class analysis that groups units (states in this study) according to similarity along a dimension (how strong its alcohol policies are). There were 18 policies, taken from the Alcohol Policy Information System of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; see here), included in the measure, belonging to categories of underage alcohol use and possession, provision of alcohol to underage individuals, alcohol server regulations (e.g., minimum age), and general availability.

The latent class analysis lead to four groups:

- states with weak policies (apart from server policies)

- states with average policy strength overall

- states with strong underage use/possession policies but otherwise average policy strength

- strong policies overall

Overall enforcement of alcohol policies in each state was determined by surveying a group of 1082 individuals from a variety of jurisdictions across the country, each representing one law enforcement agency. Researchers were connected with these individuals by asking to assess the “most knowledgeable” person in the agency regarding its alcohol policy enforcement. After rating enforcement in each of the four policy domains (e.g., provision of alcohol to underage individuals), states were placed into low, moderate, and high enforcement groups depending on their position in the group of all 50 states.

Analyses were then conducted to determine whether a person’s state’s alcohol policy group was related to three drinking measures using data from the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey (see here):

- any drinking in the past month (yes or no)

- binge drinking, defined as 5 or more drinks for a man, and 4 or more for a woman, on at least one occasion in the past month (yes or no)

- heavy drinking defined as 3 or more drinks for a man, or 2 or more for a woman, on average each day during the past month (yes or no).

Analyses were also conducted to determine whether a person’s state’s alcohol policy enforcement was related to any of these drinking measures, and whether enforcement might explain the effect of alcohol policy strength on drinking. In all analyses, authors controlled for demographic characterizes of the individual, and the total population, unemployment, and religiosity (defined as the percent who reported attending religious services at least weekly; see here) of the state in which the individual lived.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Overall, states with stronger alcohol policies (those in groups 3 and 4 in the table above) had lower proportions of any individuals that engaged in any, binge, or heavy drinking in the past month.

However, when analyzing individuals (rather than states), living in a state with strong underage drinking and possession, but otherwise average policies (group 3) had the strongest relationship with lower likelihood of any, binge, or heavy drinking controlling for the factors mentioned above (e.g., demographic characteristics). Living in a state with strong policies overall did not have significantly different relationships to drinking outcomes than living in state with average policies overall.

Living in a state with high enforcement of alcohol policies, compared to low enforcement, was related to lower likelihood of any, binge, and heavy drinking; however living in a state with moderate enforcement was no different from living in a state with high enforcement.

Also, considering enforcement in the analysis did not change the relationship between policy group and any of the drinking measures. This suggests it is unlikely that enforcement explains the effect of living in a state with strong underage drinking policies on reduced likelihood of harmful alcohol use.

Living in a state with strong underage drinking and possession policies, and policies of average or better strength otherwise, is related to lower likelihood of risky alcohol use, such as binge drinking.

Binge drinking accounts for 50% of all alcohol-related deaths, and 75% of the $250 billion alcohol costs in the U.S., strengthening alcohol policies particularly related to underage drinking might save lives and reduce the costs of alcohol use on society by reducing binge, and other harmful forms of, drinking.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Studies that assess relationships between state alcohol policies and harmful drinking could help argue for, or against, state policy changes. If studies highlight potential benefits of policy change, these changes could lead to substantial improvement in residents’ overall health and public safety (e.g., reducing liver disease, cancer, alcohol poisonings and instances of drinking and driving and violence).

This study suggests state alcohol policies, particularly those related to underage drinking, could reduce a resident’s likelihood of harmful and hazardous alcohol use. It is important to mention that analyses in this study focused on individual outcomes and also included state-level factors. This allows us to apply the positive results related to reduced likelihood of harmful drinking to individuals rather than states as a whole.

Overall, these results could have substantial implications for alcohol prevention in adolescents and young adults. For 15 to 24 year olds, alcohol use is the leading risk factor for death or life-impacting disease. Policies that reduce the likelihood of harmful alcohol use could function as an important set of prevention tools that reduce the possibility of alcohol related harms, save lives, and generally enhance adolescent and young adult health.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The clearest limitation of this study is that it analyzed alcohol policies and drinking from the same year (2009). Because the policies were not measured before the drinking outcomes, it is difficult to argue that the policy caused less binge and heavy drinking.

- Another limitation, as the authors pointed out, is that alcohol policy enforcement was assessed by surveying a knowledgeable person from a small group of law enforcement agencies in each state. Although they used a systematic approach to choose a “representative” group of law enforcement agencies, it possible that enforcement as reported by this small group in each state was not similar to enforcement across all agencies in the state, despite potentially being similar in other ways.

NEXT STEPS

The authors tested whether state enforcement of alcohol policy was related to harmful drinking. However, they did not test whether enforcement of the alcohol policies may influence how strongly those policies are related to drinking outcomes. A state may score high on alcohol harm reduction policies but if they are not enforced, there may be little relation to reductions in actual alcohol-related harms.

This could be tested by analyzing whether the interaction between policy and enforcement is related to harmful drinking (i.e., moderation analysis), and might be an interesting follow-up study.

Also, because living in a state with stronger underage drinking policies was related to less harmful drinking, another possible follow-up analysis mentioned by the authors is if this effect of stronger underage drinking policies is accounted for by reductions in harmful drinking among young people in particular.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: This study focused on how alcohol policies of the state in which someone lives is related to the likelihood of harmful drinking. More research is needed to determine whether treatment and recovery outcomes are affected by alcohol policies.

- For scientists: Taken together with other recent studies on the impact of alcohol policies, this study suggests state alcohol policies are variable, and may positively impact the likelihood that someone will engage in harmful alcohol use. If conducting alcohol related research where the individual is the unit of analysis, strongly consider including an individual’s state of residence (or overall strength of alcohol policies in their town, city, or state) in your models if not already doing so, and using multi-level analyses as authors did in this study (e.g., hierarchical linear modeling, or HLM).

- For policy makers: Strongly consider implementing or broadening the reach of evidence-based policies shown to reduce harmful drinking. Examples of such policies can be found in the Alcohol Policy Information System by clicking here.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: In addition to your patients’ social context – which is often considered when providing therapy – it may also be helpful to think about alcohol related policies in your town, city, or state, and the impact on your patients alcohol related behaviors. For example, young adult patients living in communities with less restrictive and/or less enforced laws regarding alcohol sales to, and possession among, minors may be at greater risk for exposure to peer drinking, enhancing the likelihood of cue-induced craving and relapse.

CITATIONS

Erickson, D. J., Lenk, K. M., Toomey, T. L., Nelson, T. F., & Jones-Webb, R. (2015). The alcohol policy environment, enforcement and consumption in the United States. Drug Alcohol Rev. doi:10.1111/dar.12339