Does initiating medication-assisted treatment in the emergency room result in better outcomes?

Opioid use in the U.S. is a growing public health epidemic.

One evidence-based option for people with opioid use disorder is medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with buprenorphine-naloxone (“Suboxone”) to decrease symptoms of withdrawal and cravings.

Since trained physicians can prescribe buprenorphine-naloxone—as opposed to methadone, which requires visits to licensed programs—it is possible to incorporate this form of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) in a variety of medical settings.

The emergency department may be an optimal setting for screening and intervention for opioid use disorder due to high volumes of patients and the potential for staff to leverage patients’ motivation to change. By adding an MAT component to regular screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) protocols, patients can cease illicit opioid use more immediately and avoid health consequences that could occur during the delay between referral and treatment engagement.

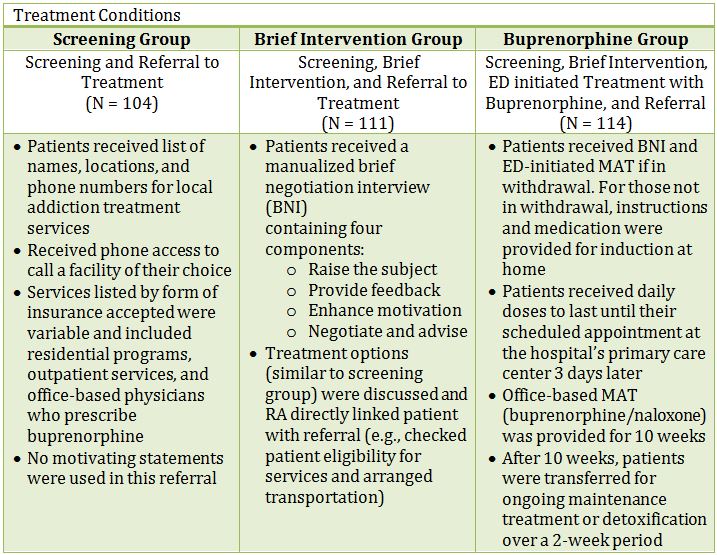

The primary outcome, engagement in treatment, was defined as enrollment and receiving formal addiction treatment on the 30th day following the index visit, confirmed by contact with the facility and/or clinician. Formal addiction treatment referred to a range of clinical settings including residential programs and office-based medication-assisted treatment (MAT).

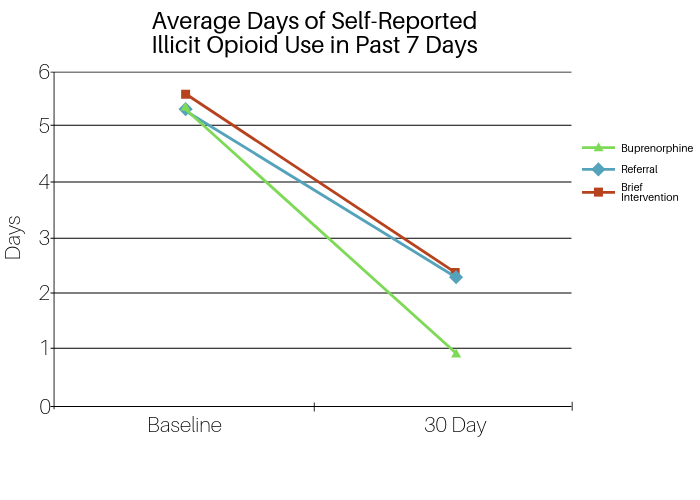

Secondary outcomes collected at 30 days included self-reported number of days of illicit opioid use in the past week, urine toxicology for opioid use, a self-report measure of HIV risk-taking behavior (drug use and sexual behavior), and use of addiction treatment services.

Patients were three quarters male, three quarters White, and 31 years old on average. 80% had some form of health insurance, and over 75% reported full- or part-time employment. About 34% of patients came to the emergency department solely to seek treatment, while 9% presented with an overdose. The rest of the participants were identified through the screening process. Over 70% of patients reported lifetime history of drug treatment, and over half had a coexisting mental health issue.

Regarding the primary outcome, treatment engagement rates were significantly higher for patients in the buprenorphine-naloxone group (89 of 114; 78%) than the referral (38 of 102; 37%) and brief intervention (50 of 111; 45%) groups.

The buprenorphine-naloxone group reported significantly greater reduction in mean number of days of illicit drug use per week (reduction from 5.4 to 0.9 days) compared to the referral group (5.4 to 2.3 days) and brief intervention group (5.6 to 2.4 days).

Rates of negative urine toxicology tests for opioid use did not differ significantly by group (54% for referral, 43% for brief intervention, and 58% for buprenorphine). All three groups showed significant reductions in HIV risk from baseline to 30 days, though these differences were not significant across groups.

Regarding use of treatment services, there was no difference across groups for mean number of outpatient visits, but patients in the referral and brief intervention groups used inpatient services at higher rates than the buprenorphine group (37%, 35%, and 11%, respectively).

In a subgroup analysis, patients who went to the emergency department specifically seeking treatment had similar rates of engagement as the full sample, suggesting that this initial motivation did not impact their outcome at 30 days.

IN CONTEXT

In a randomized trial of emergency department interventions for patients with opioid use disorder, the group initiating buprenorphine-naloxone treatment experienced higher rates of treatment engagement and fewer self-reported days of illicit opioid use than patients in the referral and brief intervention groups. However, there was no difference between the groups when analyzing urine test results. The authors note this discrepancy may be due to the fact that opioids can be detected in urine for up to 72 hours, so a urine sample from one point in time may not accurately reflect frequency of use.

While all three strategies went beyond the current standard of emergency department care, the results support emergency department-initiated buprenorphine-naloxone treatment as the most effective means of intervention.

The window of time between referral and appointment attendance may result in loss of motivation to stop using opioids and provides more opportunity for a patient to experience consequences of drug use (e.g., overdose or incarceration).

A strength of this intervention is the reduction in time from screening to initiation of care. Despite an RA’s best efforts, referring a patient to care is unlikely to have an impact until the patient arrives at the scheduled appointment and formally begins treatment. By initiating MAT the same day as screening, patients begin the recovery process sooner.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Before widespread implementation of similar interventions, results should be replicated in emergency departments in other settings (e.g., smaller hospitals or rural areas).

- Additionally, emergency department physicians need to undergo training to be able to prescribe buprenorphine in order for this intervention to be implemented.

NEXT STEPS

Since all services were provided to patients free-of-charge, it is unknown how cost or lack of insurance may deter patients from taking advantage of similar programs that cannot provide free services. Cost-effectiveness analyses of this intervention would also provide information needed to determine if this type of emergency department-initiated buprenorphine treatment is likely to be adopted and implemented.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) can help support patients by decreasing withdrawal symptoms and cravings while they are acquiring recovery resources. Since MAT is not part of routine training for emergency department physicians, look for a local provider who is able to provide buprenorphine. Other resources in addition to MAT are also available. For family members: If your family member has received a referral, you can help by ensuring that they attend their scheduled appointment (e.g., by providing transportation to the clinic or treatment center).

- For scientists: Similar studies should be performed in other emergency departments to see if the results are replicated. Studies with longer periods of follow-up are also needed to evaluate long-term impact of emergency department-facilitated engagement in care on substance use outcomes. Cost-effectiveness analyses are needed to strengthen the evidence for scaling up this sort of intervention.

- For policy makers: While current evidence is compelling, replication of results is needed to support widespread implementation of emergency department-initiated buprenorphine. Given opioid-related overdose and mortality risks, this appears to be an important intervention worthy of funding in the future.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: If you are interested in providing this intervention, it is important to identify a network of community services and treatment centers for continuing care so that patients have a place to go after initial stabilization with medication.

CITATIONS

D’Onofrio, G., O’Connor, P. G., Pantalon, M. V., Chawarski, M. C., Busch, S. H., Owens, P. H., . . . Fiellin, D. A. (2015). Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(16), 1636-1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474