Does Drinking in Moderation Help or Hurt the Long-Term Health of Your Brain?

Media reports often highlight the presumed health benefits of moderate drinking, but those benefits are still debated in the scientific community.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In the U.S., Federal Dietary guidelines define high-risk drinking as:

- 8 or more drinks per week for women

- 15 or more drinks per week for men

1 U.S. standard drink being the equivalent of 12 oz of 5% beer or 1 shot of 80-proof liquor (i.e., 14 grams of pure ethanol).

High risk drinking is globally attributed to significant death, disability, a variety of chronic medical conditions, and at high levels, cognitive impairment.

But, what if one drinks alcohol at, or below, these levels? Are they less likely to experience alcohol’s negative effects? Moderate alcohol consumption is sometimes portrayed in the media as a promotor of longevity and optimal health. Indeed, some studies suggest that light-to-moderate drinking may benefit mental and/or physical health, relative to abstinence and heavy drinking. On the other hand, associations between light alcohol consumption, chronic disease, and mortality are also reported.

To date, many of these investigations have been concerned with short-term outcomes or lack consideration of additional lifestyle factors that can influence mental and physical health, such as exercise, social activity, and history of psychiatric disorders. Varying control of these factors between studies has likely contributed to conflicting results.

In an attempt to answer some of these questions, the current study assesses whether average drinking habits, collected over a 30-year period, predict changes in cognitive function and structural integrity of the brain, while adjusting for many potentially influential factors.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Five hundred and fifty men (80%) and women (20%) were randomly selected from a larger longitudinal study (the Whitehall II study) assessing the relationship between socioeconomic status, stress, and cardiovascular health among individuals (~43 years old) residing in the UK.

- MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

The Whitehall II study began in 1985 and followed participants for approximately 30 years. Data, including sociodemographics (e.g., age, social activity), cognitive function, and alcohol use variables, were collected at approximately 5 year intervals throughout the duration of the study.

Among the participants randomly selected for the present study, none had a history of alcohol dependence according to a brief screening questionnaire (determined with the CAGE at all study sessions across 30 years, which addresses attempts to reduce drinking, drinking-related annoyance, guilt, and realizations). All participants completed brain scans at the end of the 30-year period. Brain scans were performed with diffusion tensor (DTI) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which produces detailed images of the brain that allow for the measurement of various structural attributes (e.g., size, shape, integrity) in specific brain regions and the strength of connections between these regions. The authors were interested in measures of gray-matter density (the density or volume of brain cells, which is linked with various cognitive abilities), visual ratings (clinician ratings using a standard medical scale) and computer derived (% of brain region volume relative to whole brain volume) measures of atrophy (decreased size of brain cells and the connections between them), as well as white matter integrity (the degree to which nerve fiber bundles, that allow communication between brain regions, are structurally intact). At the time of the scan, cognitive functions that had been repeatedly assessed in previous years were examined once again. Additional neuropsychological tests that assessed a wide variety of cognitive domains and that participants had not performed in previous years were also administered. Information regarding psychiatric diagnoses and prescribed medication use was simultaneously collected.

Measures of self-reported weekly alcohol consumption, averaged across all 5 year intervals were used to identify various drinker groups. For the sake of this summary, all alcohol consumption quantities were converted to US number of standard US drinks.* Initial analyses compared sociodemographics and participant characteristics in two groups of drinkers: safe versus unsafe. According to UK Department of Health Guidelines, safe drinkers consisted of men who drank an average of less than 12 standard US drinks and women who drank an average of less than 8 standard US drinks. Individuals whose average weekly alcohol consumption fell outside these bounds were deemed unsafe drinkers. In subsequent analyses, the authors divided participants into 6 groups based on weekly average alcohol consumption across the 30-year period: 1) < .5 drinks (this group was defined in the study as ‘abstinent’), 2) .5 – 4 drinks, 3) 4 – 8 drinks, 4) 8 – 12 drinks, 5) 12 – 17 drinks, and 6) 17 or more standard drinks. These groups were used to determine whether weekly average alcohol consumption predicted brain structure and/or cognitive function, while controlling for a variety of sociodemographic factors. Characteristics statistically controlled for included age, sex, premorbid IQ (estimate of baseline intellectual functioning), risk of stroke (as determined by the Framingham risk assessment – considers factors such as smoking, cardiovascular health, and diabetes), lifetime diagnosis of major depression, exercise frequency, social activities (social club attendance, visits with family/friends), and current use of psychotropic medications.

When participant characteristics were compared between safe and unsafe drinkers, unsafe drinkers had higher premorbid IQ, higher risk of stroke, as well as higher proportions of men and smokers at the time of brain imaging. Groups were similar with respect to education (12-17 years), prescribed psychotropic medication use (14%), and history of major depressive disorder (18%).

*UK alcohol units in the original study were converted to number of drinks based on standard US alcohol units

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Higher quantities of average alcohol consumption per week were associated with lower gray-matter density.

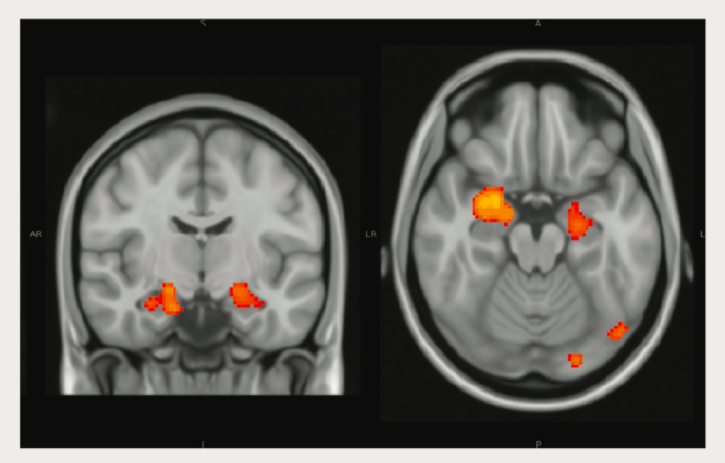

This was true in the hippocampus (a brain region that plays an important role in memory, learning, and emotion) and the amygdala (region implicated in emotion and motivation). These regions can be seen in the figure below. Red and yellow indicate brain regions for which weekly alcohol consumption significantly predicted gray-matter density.

The more alcohol consumed, the greater the likelihood of atrophy; Drinking less than 14 units per week did not increase or decrease odds of atrophy, relative to abstinence. Compared to abstinent participants, 14 or more units per week showed increased odds of hippocampal atrophy, and 30 or more average weekly units of alcohol equaled the greatest odds of hippocampal atrophy.

Using MRI measures, alcohol consumption consistently predicted volume of the hippocampus. Gender was found to affect results. Weekly alcohol consumption did not predict hippocampal atrophy in women, only men. This study had a relatively small number of female participants as it is harder to detect statistical differences with smaller sample sizes. Authors found a similar pattern of results for white matter; higher average weekly alcohol consumption predicted less white matter integrity.

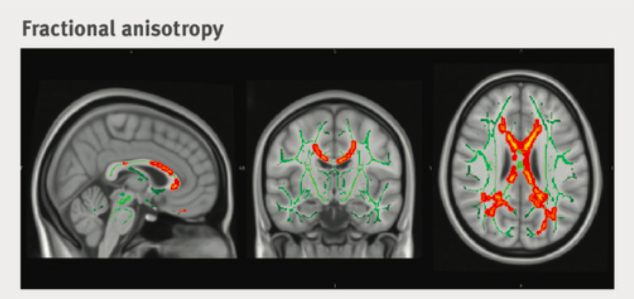

This was true in the corpus callosum (a large bundle of nerve fibers that transmits information between the left and right sides of the brain), including lower fractional anisotropy and higher diffusivity – measures that both reflect less organized movement of water molecules along a nerve fiber bundle, suggesting weaker connections between brain regions. The corpus callosum can be seen in the figure below. Red and yellow indicate regions of this fiber bundle for which weekly alcohol consumption significantly predicted fractional anisotropy.

Average weekly alcohol consumption associated with cognitive function. Regarding longitudinal measures over a 30 year period higher weekly consumption predicted a steeper decline in lexical fluency (ability to mentally retrieve and produce words based on their phonetic properties). Over 30 years lexical ability:

- Decreased 14% among individuals who drank 7 – 14 units per week

- Decreased 17% among those who drank 14 – 21 units

- Decreased 16% among drinkers consuming more than 21 units per week

These declines were significantly greater than those observed among abstainers. Rate of decline in lexical fluency among participants drinking 1 – 7 units per week did not differ from those of abstinent individuals.

Changes in other cognitive domains over 30 years, including semantic fluency (ability to mentally retrieve and produce words based on their conceptual properties) and short-term memory (ability to mentally retain incoming information and recall it after a short delay) did not differ by weekly alcohol use.

Alcohol consumption and age predicted hippocampal volume and corpus callosum integrity. Alcohol use directly and indirectly predicted cognitive decline in lexical fluency.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT?

Demonstrating poorer long-term neurobehavioral outcomes as a function of average weekly alcohol consumption has important implications. Drinking as little as 4 drinks per week was associated with worse neurocognitive consequences than abstinence.This is particularly alarming given that moderate drinking guidelines in the U.S. permit up to three and one-half times these weekly alcohol values (among men). Although the most recent U.K. guidelines are more conservative, they still permit weekly consumption at twice this rate.

News and media reports have frequently highlighted the presumed benefits of moderate drinking. Despite limitations in the current study (see below), these data suggest that moderate drinking not only fails to benefit neurocognitive health, but may alternatively be associated with greater neurostructural degeneration and more rapid cognitive decline (independent of age). Furthermore, abstinence (defined here as drinking less than half a standard US drink per week) does not appear to increase risk of cognitive decline over time, as previously suggested by earlier investigations.

This study reveals a relationship between drinking and specific measures of neurocognitive integrity, controlling for an array of lifestyle factors that are likely to interact with alcohol to influence brain structure and function. Although no single study will definitively tell us if drinking in moderation is invariably ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for our health, investigations like these can help guide alcohol consumption behaviors among drinkers without alcohol use disorder to facilitate optimal health.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The study sample consisted of relatively few women and was primarily made up of educated middle class men residing in the UK. Therefore, findings may not generalize to all sub-populations.

- Brain imaging was only collected at the end of the 30-year study. Although imaging technology was less widely accessible in previous decades, the lack of longitudinal neuroimaging data limit interpretation to cross-sectional outcomes. Therefore, changes in structural integrity as a function of lifetime drinking habits could not be assessed.

- Average weekly alcohol consumption, as it was derived, could potentially mask periods within the 30-year timeframe in which drinking patterns changed. The authors note that individuals who drank more at the beginning of the study tended to reduce their weekly consumption over the course of 30-years. Average measures would not have differentiated between those who decreased consumption and those with stable drinking habits. As a result, qualitative differences between participants in the same drinking group may exist. However, it is not clear if the demographic, neurostructural, or cognitive data would differ among those who reduced their weekly alcohol intake across the study.

- Of the neurocognitive tests administered at the time of brain imaging, only two were administered in previous sessions. Both of these tasks assessed relatively simple cognitive skills within the verbal domain (as opposed to visual). Repeated measures were obtained for a third task (short-term memory), but this task was not performed at the time of neuroimaging. Although a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests was added to the protocol and completed by participants at the time of imaging, none of these tasks had been previously administered and longitudinal changes in these cognitive domains could not be assessed. Therefore, the influence of alcohol consumption on the cognitive trajectories of other domains is not entirely clear.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Studies that collect information about alcohol’s associated long-term outcomes shed light on the harms associated with drinking across the lifespan. The negative effects of repeated heavy alcohol use in individuals with alcohol use disorders are well characterized. Studies like this one remind us that alcohol-related harm is not necessarily limited to those with a diagnosed alcohol-use problem – alcohol is a neurotoxin that disrupts normal functioning of brain cells. While alcohol’s neurotoxic effects are more readily apparent in individuals who drink to excess, this study suggests that they might also be observed over time among moderate drinkers, though to a lesser extent. Consuming less alcohol per week may serve to reduce the risk of faster neurocognitive decline across the lifespan.

- For scientists: Using measures of alcohol consumption and cognition, collected over a 30-year period, this UK-based investigation demonstrates a relationship between alcohol consumption and long-term neurocognitive decline in a dose-dependent manner and provided evidence of alcohol’s dose-dependent relationship to cognitive decline. Drinking 8 or more standard U.S. drinks per week predicted worse atrophy of the hippocampus – higher average consumption paralleled more significant deterioration. As few as 4 drinks per week was associated with more rapid decline in lexical fluency across 30 years. Although some studies suggest health-related benefits of moderate alcohol consumption, findings across the literature are mixed. A number of previous investigations lack consideration of potentially influential lifestyle factors, rely on cross-sectional samples and retrospective reports, or limit observation to a brief period in time. This investigation overcame several of these limitations, most notably its assessment and consideration of several environmental, medical, and sociodemographic factors in statistical models. Despite its own set of limitations (e.g., male-dominated sample), this study permitted stronger conclusions about lifetime alcohol consumption and its relationship to long-term neurobehavioral trajectories. Further investigation is needed to determine the associations between drinking patterns and neuropsychological functions in other cognitive domains across the life span.

- For policy makers: Research studies like this one provide a unique opportunity to better understand alcohol’s dose-related long-term health outcomes. Although neurocognition is just one component of overall health, it’s a particularly important one that has the potential to influence other components like physical health and use of medical services. In this study, higher rates of average weekly alcohol consumption were associated with worse neurocognitive outcomes that declined as a function of alcohol dose. This included more rapid decline of verbal fluency with as little as 4 drinks per week and hippocampal atrophy with as few as 8. Poorer neurocognitive integrity across the lifespan can increase economic and societal burden. Hippocampal atrophy, for example, is a sensitive indicator of Alzheimer’s disease, for which global societal and economic cost was estimated at 818 billion US dollars in 2015 (Alzheimer’s Disease International). Interestingly, impaired verbal fluency is an early sign of Alzheimer’s Disease that often precedes diagnosis. Given that alcohol was associated with lexical fluency and hippocampal atrophy, both of which are associated with Alzheimer’s, these findings have important implications. Although further investigation is needed to confirm and extend these findings, reconsideration of current national drinking guidelines may be warranted – particularly in the U.S. where Federal Dietary guidelines for moderate drinking (lower-risk) permit up to 7 drinks per week for women and up to 14 for men. Additional funding dedicated to long-term studies of this type will certainly aid development of appropriate federally-defined guidelines.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study incorporates longitudinal and cross-sectional data suggesting that alcohol consumption, even at low and moderate levels, is associated with more rapid cognitive decline and poorer structural integrity of the brain. Poorer neurocognitive outcomes, including more rapid decline in lexical fluency and greater hippocampal atrophy, declined as a function of average weekly alcohol consumption. Further research is needed to determine the generalizability of these findings. However, physicians and medical professionals might benefit from consideration of these findings when advising patients of low-risk drinking levels. These data may be particularly important for those treating patients with substance use disorders who either reduce their alcohol use as a harm-reduction technique or who use alcohol at moderate levels but are in recovery from other (non-alcohol) substance use disorders; many populations with substance use disorder are already at increased risk for neurocognitive deficits and those in recovery who continue to use alcohol at low/moderate levels could potentially hinder recovery-associated neurocognitive repair or be at even greater risk for long-term neurocognitive degeneration. However, additional investigation is needed to systematically guide clinical applications.

CITATIONS

Topiwala, A., Allan, C. L., Valkanova, V., Zsoldos, E., Filippini, N., Sexton, C., … & Kivimäki, M. (2017). Moderate alcohol consumption as risk factor for adverse brain outcomes and cognitive decline: longitudinal cohort study. bmj, 357, j2353.