Drug checking services equip people who use drugs with valuable information about what is in the drugs that they use. Researchers in this qualitative study explored client and provider attitudes toward drug checking services and how they use them.

Drug checking services equip people who use drugs with valuable information about what is in the drugs that they use. Researchers in this qualitative study explored client and provider attitudes toward drug checking services and how they use them.

l

Drug checking services offer an approach to harm reduction in which people who use drugs can test the chemicals that make up the drugs they intend to use. This can reveal if they contain harmful substances the person may not want to consume, such as fentanyl and xylazine, which can substantially increase risk for overdose. Having this information provides them with the opportunity to not use the drugs if they are contaminated or to take extra precautions if they choose to use them anyway (e.g., not using alone, using smaller amounts of the drug, using the drug more slowly).

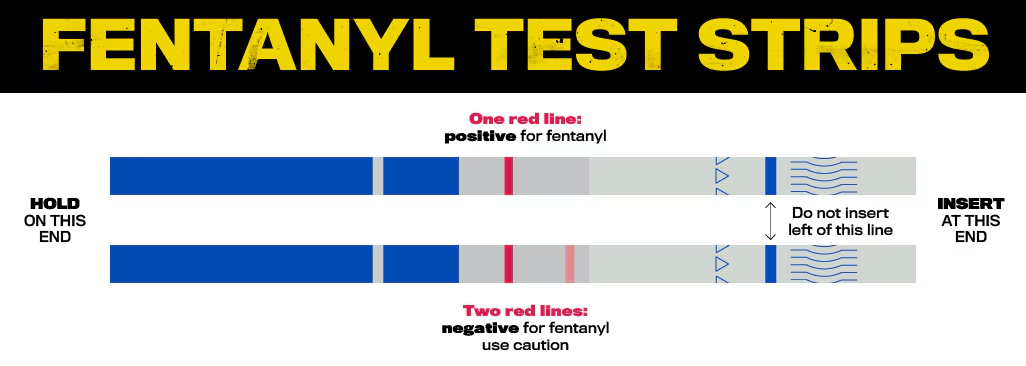

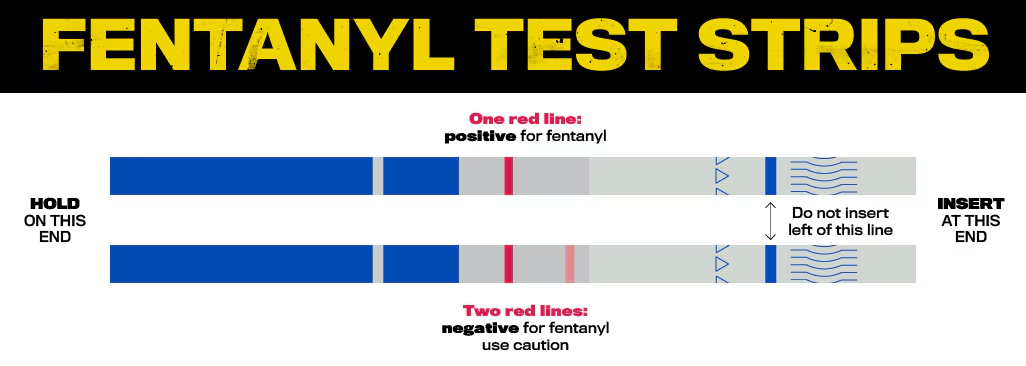

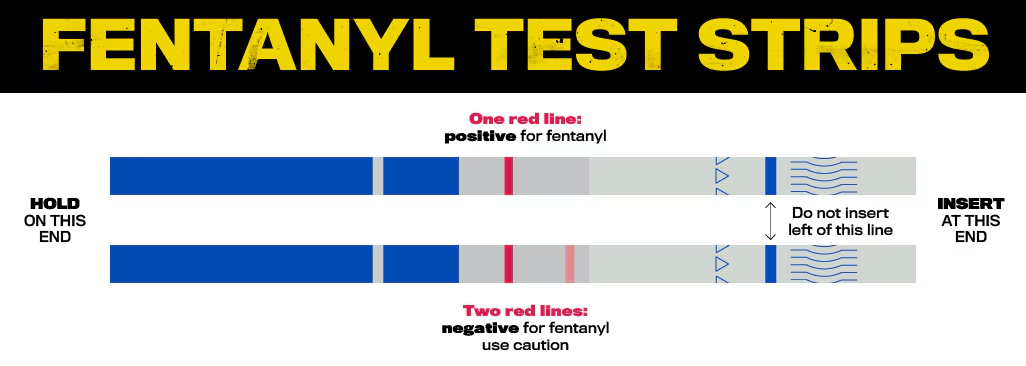

One of the most common forms of drug checking resources are fentanyl testing strips. Fentanyl test strips are small, portable strips of paper that can detect fentanyl in very small concentrations. While their portability and accessibility make them especially useful for outreach and street use, their limitation is that they do not provide information on how much fentanyl is present or if other substances are present, only that fentanyl is present. In cases where a person may want to use fentanyl but want to know the concentration of it, or if someone wishes to have the exact breakdown of the substances making up the drugs they want to use, another form of drug checking called spectrometry may be more useful.

Spectrometry often must be performed in a lab setting by a trained technician, making it less accessible to the general public, but can detect the presence and concentrations of a variety of substances within a drug, including other sedatives which can increase risk for overdose. More recently, spectrometry services are being offered at harm reduction centers, such as syringe service programs and overdose prevention centers.

These services have been implemented in Europe, especially in situations where more people may be using recreational drugs (e.g., music festivals). While drug checking services are not as common in the US and Canada as they are in Europe, research suggests that there is strong interest in them among both people who use drugs and harm reduction providers. The researchers in this study explored how clients and providers of drug checking services value and use these services. Such research can help inform the utility of drug checking services, which can help shape policy.

In this qualitative study, the research team conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with clients and providers of drug checking and harm reduction services to examine the value of such services and how they are operated. The interviews were conducted virtually and in-person in San Francisco in 2022.

Providers included 11 people who provided direct clinical and harm reduction services to people who use drugs, as well as professionals who have expertise with drug checking, such as researchers, who worked in the US and Canada. The researchers recruited providers via email based on their expertise first (i.e., purposive sampling) and then through recommendations (i.e., snowball sampling). Provider participants were compensated $100 for their time.

Interviews with providers were conducted using the Zoom virtual platform between June and November 2022, with each lasting approximately 45-60 minutes. These interviews assessed their perspectives on the state of the drug market in their area, and the perceived needs of and challenges faced by their clients, as well as their attitudes and experiences with drug checking methods and programs and integrating them into existing services.

Clients included 13 people who use drugs and were receiving harm reduction services at an agency where several different forms of drug checking were offered. Participants were recruited by 2 members of the study team who were interviewers and program staff from 4 harm reduction programs in San Francisco (i.e., convenience sampling). Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years of age and current use of fentanyl, heroin, or methamphetamine. Clients were not eligible however if they were currently intoxicated, or otherwise not able to provide informed consent. Intoxication was defined by an inability to respond to basic questions, responding incoherently, or participant reporting that they were too high to continue. Client participants were compensated $25 cash for their time.

Interviews were conducted in-person in San Francisco during 1 week in November 2022 and lasted approximately 30-60 minutes. They asked participants about their history of drug use, and experiences with harm reduction services, as well as their awareness of, attitudes about, and experiences with various forms of drug checking.

Interviews with both providers and clients were recorded and the audio was then transcribed. After reviewing the transcripts, the research team identified major themes and sub-themes from the interview summaries. Then, a coding scheme was developed based on codes from the interview guide and themes. The interviews were coded using this scheme.

Among the provider participants, there were 2 clinical providers, 4 researchers, and 5 harm reduction service providers. The 2 clinicians were US-based, 3 of the service providers were US-based while 1 was based in Canada, and 3 of the researchers were US-based while 1 was based in both the US and Canada. Among the client participants, 8 identified as men and 5 identified as female. The majority were between the ages of 30 and 49 and identified as White.

There were differences in the extent to which clients reported using drug checking, their attitudes towards it, and how they respond to results

While almost all clients reported that they have had some experience with fentanyl test strips, their attitudes toward them differed. Some expressed concerns that they were difficult to use or were unreliable. Others reported that they rely on them for unique information about what is in their drugs that they would not get otherwise.

Fewer clients had heard of spectrometry. Some were excited and interested in it, while others were concerned about judgements from the community, bystanders calling the police, and being harassed by law enforcement. Among those who have used it, reports were positive, but also included complaints about how often the results indicated there were substances in their drugs other than what they thought they were purchasing.

There were also differences in how clients reported using the results of drug checking. Some reported that they avoided buying drugs that were contaminated with fentanyl. Others reported they did not want to test their drugs because, for instance, they did not want to have to not use the drugs if they were contaminated, especially if they were going to go through withdrawal, and would not be able to return it for a refund.

Providers agreed drug checking can save lives, but questioned its role in behavior change and wide-scale impact

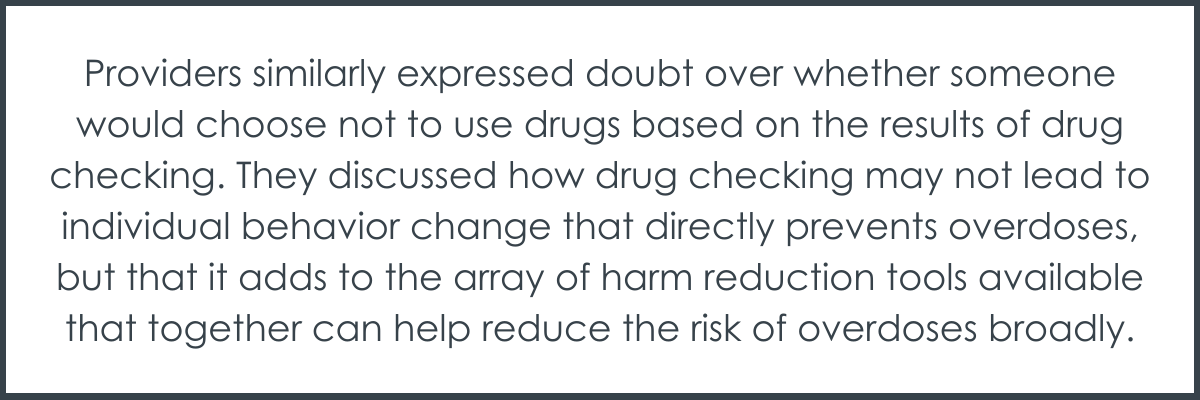

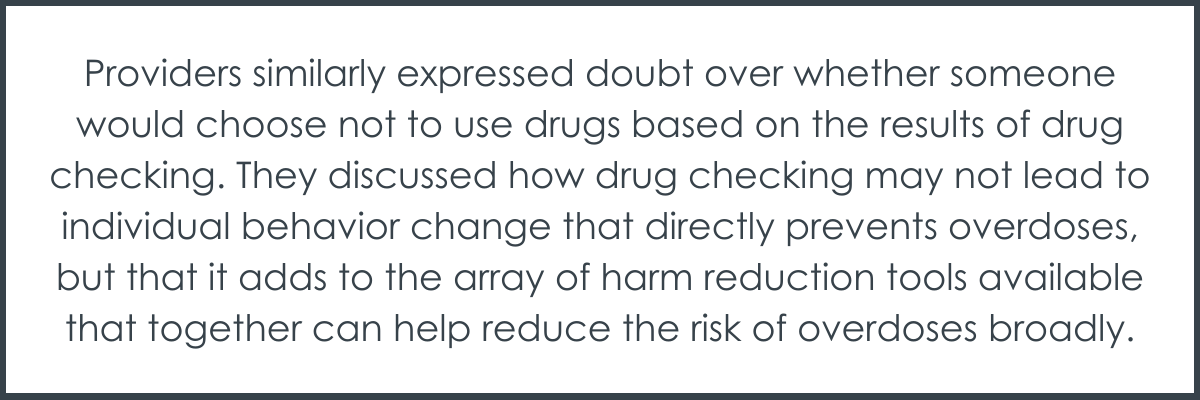

Providers similarly expressed doubt over whether someone would choose not to use drugs based on the results of drug checking. They discussed how drug checking may not lead to individual behavior change that directly prevents overdoses, but that it adds to the array of harm reduction tools available that together can help reduce the risk of overdoses broadly.

Providers also acknowledged that drug checking may save lives, but questioned the impact it might have on preventing overdoses, discussing how it is difficult to prove that prevention efforts have been effective and how the constantly changing drug market may limit the effects of drug checking.

Drug checking provides valuable information, bodily autonomy, and validation

Providers described how people who use drugs have the right to know what they are putting in their bodies, how drug checking can empower people to make informed decisions, and how it can validate people’s experiences using drugs (e.g., confirming their suspicion that the drugs they took had fentanyl in it).

Clients similarly discussed how drug checking is an important tool they can couple with their own intuition and expertise, which allows them to make informed decisions about their drug use (e.g., testing their supply when they suspect there is fentanyl in it). They also described how it is important to know what you are putting into your body and how they care about their health and well-being. Examples that demonstrate decisions were made that prioritize health were given, including the choice not to smoke out of foil since it is not healthy to do so, the decision to reduce marijuana use due to a sensitive respiratory system, and not wanting to “be a statistic” given the risks of the current drug market.

Drug checking as a tool to help naturalistically regulate drug markets

Clients and providers both discussed how drug checking services could serve as a tool to help regulate the drug market and vet sellers, helping to keep people who use drugs safer. For example, if people knew what was in their drugs before buying it, they could hold sellers accountable because people would be empowered to get it elsewhere. In other words, they would be fully informed about what they are purchasing and if their supplier can be trusted.

Clients shared examples of testing drugs in front of the seller and, if using spectrometry, bringing documentation of what the results were, both of which keeps sellers honest. Providers discussed how drug checking could also benefit sellers who get drugs second-hand and do not necessarily know what it is in it, which was echoed by a client who also sells drugs and expressed wanting to know the chemical balance of what he is selling to make sure it is good.

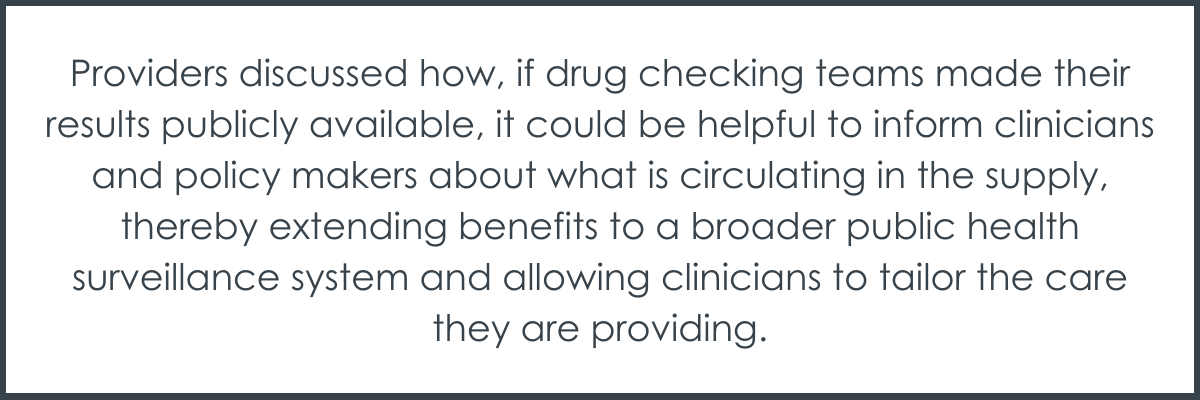

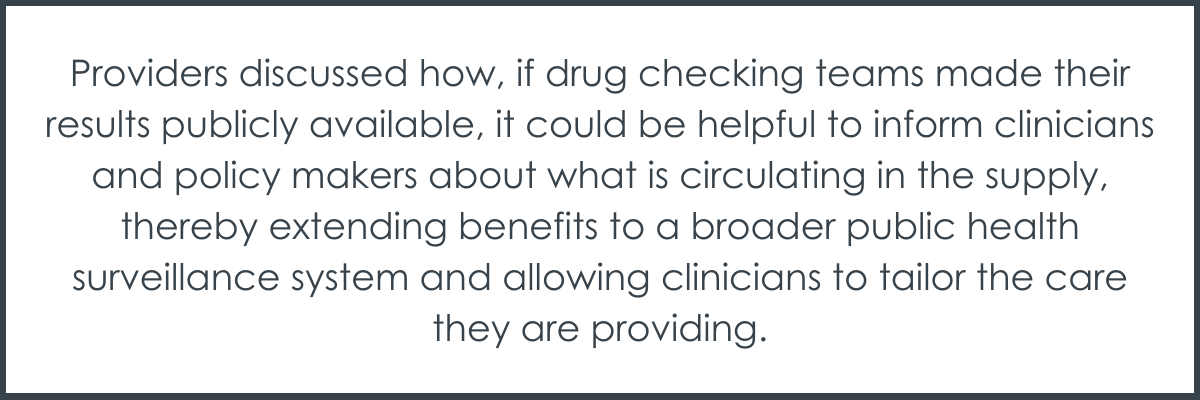

Participants also discussed how verifying the contents of drugs fills a policy gap, since illicit drug use is not legal and therefore not monitored and regulated. Clients equated this to knowing what is in the food we eat, with one client expressing how it is especially important to know what is in the drugs being used because they do not know where they are coming from and who is making them. Providers expressed how drug checking is only necessary “until prohibition goes away” and the supply could be regulated and safe. Additionally, providers discussed how, if drug checking teams made their results publicly available, it could be helpful to inform clinicians and policy makers about what is circulating in the supply, thereby extending benefits to a broader public health surveillance system and allowing clinicians to tailor the care they are providing.

Concerns about the quickly changing drug supply and the need for multiple approaches to harm reduction

Clients and providers both expressed concerns that the drug supply changes so quickly that spectrometry libraries against which results can be compared may not be able to keep up, which can limit the accuracy of the results. One provider also expressed concern that “we’re just throwing yet another technology at a much bigger problem” and discussed the need for multiple approaches to harm reduction (e.g., syringe service programs), as well as the need to address important social determinants of health, such as housing.

The research team explored how clients and providers of drug checking services value and use these services by conducting semi-structured interviews. In sum, clients reported relying on drug checking services frequently and behavior change given positive results, though others expressed concerns about accuracy and ease of use, concerns about law enforcement’s reaction to them, and not being sure the results would prevent them from using, if the drugs were contaminated. Providers similarly shared the uncertainty about how people might use positive results and questioned whether drug checking services would make a wide scale impact but acknowledged that they can save individual lives for those who use them. Both clients and providers expressed that drug checking services offers people who use drugs valuable information about what is in their drugs, which provides bodily autonomy and fills a policy void by providing some regulation that is otherwise absent.

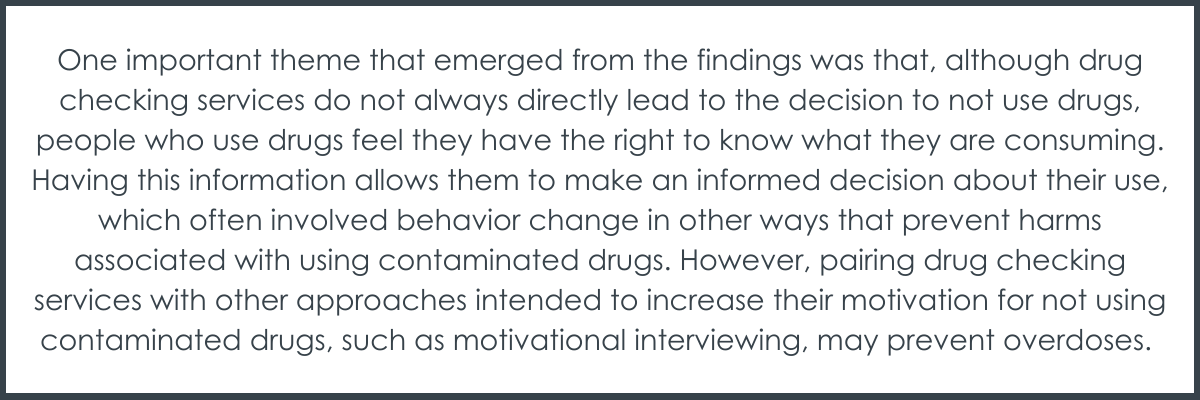

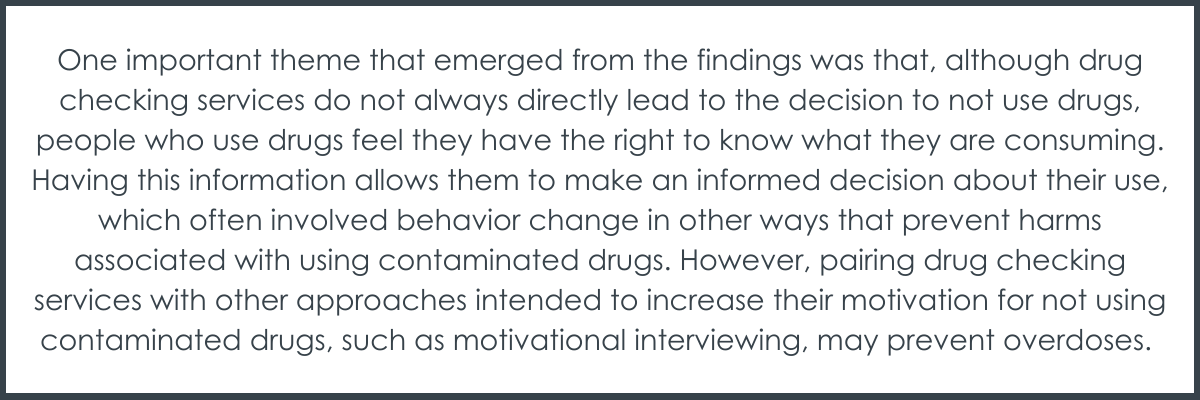

While this was a small study of just 24 participants in one US city (as is the case for many qualitative studies about unique samples and experiences), the results may provide important insights into how clients and providers of drug checking services perceive the operationalization and value of these services. One important theme that emerged from the findings was that, although drug checking services do not always directly lead to the decision to not use drugs, people who use drugs feel they have the right to know what they are consuming. Having this information allows them to make an informed decision about their use, which often involved behavior change in other ways that prevent harms associated with using contaminated drugs. However, pairing drug checking services with other approaches intended to increase their motivation for not using contaminated drugs, such as motivational interviewing, may prevent overdoses.

In addition, because drug checking services are not mainstream in the US and cannot yet reach every person who uses drugs, they cannot yet have a population-level effect on overdose rates. However, they do offer one harm reduction strategy that could be used in combination with other strategies (e.g., syringe services) that together could make a large-scale impact, if legal and offered widely. Accordingly, drug checking services should be considered within the broader framework of harm reduction for a larger impact on preventing overdoses. Despite the potential public health benefits of harm reduction strategies, including drug checking, syringe services, and safe supply initiatives, many of them are not supported by policy in the US, but are legal and mainstream in other countries, such as Europe.

Finally, one provider importantly highlighted that implementing drug checking services without considering the basic needs of humans and social determinants of health (e.g., housing, employment, access to health care) would neglect the larger structural and systemic problems that contribute to drug use disorders and overdoses. Harm reduction services can help to address the problem immediately, which is critically needed amidst the continuing overdose crisis, but structural and systemic changes are needed as well.

While drug checking services are best understood as one of many harm reduction strategies, and larger systemic changes may be needed to make a wide-scale impact on overdose rates, these services empower people who use drugs to make informed decisions about their drug use. People who use drugs may value this information, and in the absence of regulation (e.g., “safe supply” initiatives), would not be able to do so otherwise.

Moran, L., Ondocsin, J., Outram, S., Ciccarone, D., Werb, D., Holm, N., & Arnold, E. A. (2024). How do we understand the value of drug checking as a component of harm reduction services? A qualitative exploration of client and provider perspectives. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(1), 92. doi.: 10.1186/s12954-024-01014-w

l

Drug checking services offer an approach to harm reduction in which people who use drugs can test the chemicals that make up the drugs they intend to use. This can reveal if they contain harmful substances the person may not want to consume, such as fentanyl and xylazine, which can substantially increase risk for overdose. Having this information provides them with the opportunity to not use the drugs if they are contaminated or to take extra precautions if they choose to use them anyway (e.g., not using alone, using smaller amounts of the drug, using the drug more slowly).

One of the most common forms of drug checking resources are fentanyl testing strips. Fentanyl test strips are small, portable strips of paper that can detect fentanyl in very small concentrations. While their portability and accessibility make them especially useful for outreach and street use, their limitation is that they do not provide information on how much fentanyl is present or if other substances are present, only that fentanyl is present. In cases where a person may want to use fentanyl but want to know the concentration of it, or if someone wishes to have the exact breakdown of the substances making up the drugs they want to use, another form of drug checking called spectrometry may be more useful.

Spectrometry often must be performed in a lab setting by a trained technician, making it less accessible to the general public, but can detect the presence and concentrations of a variety of substances within a drug, including other sedatives which can increase risk for overdose. More recently, spectrometry services are being offered at harm reduction centers, such as syringe service programs and overdose prevention centers.

These services have been implemented in Europe, especially in situations where more people may be using recreational drugs (e.g., music festivals). While drug checking services are not as common in the US and Canada as they are in Europe, research suggests that there is strong interest in them among both people who use drugs and harm reduction providers. The researchers in this study explored how clients and providers of drug checking services value and use these services. Such research can help inform the utility of drug checking services, which can help shape policy.

In this qualitative study, the research team conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with clients and providers of drug checking and harm reduction services to examine the value of such services and how they are operated. The interviews were conducted virtually and in-person in San Francisco in 2022.

Providers included 11 people who provided direct clinical and harm reduction services to people who use drugs, as well as professionals who have expertise with drug checking, such as researchers, who worked in the US and Canada. The researchers recruited providers via email based on their expertise first (i.e., purposive sampling) and then through recommendations (i.e., snowball sampling). Provider participants were compensated $100 for their time.

Interviews with providers were conducted using the Zoom virtual platform between June and November 2022, with each lasting approximately 45-60 minutes. These interviews assessed their perspectives on the state of the drug market in their area, and the perceived needs of and challenges faced by their clients, as well as their attitudes and experiences with drug checking methods and programs and integrating them into existing services.

Clients included 13 people who use drugs and were receiving harm reduction services at an agency where several different forms of drug checking were offered. Participants were recruited by 2 members of the study team who were interviewers and program staff from 4 harm reduction programs in San Francisco (i.e., convenience sampling). Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years of age and current use of fentanyl, heroin, or methamphetamine. Clients were not eligible however if they were currently intoxicated, or otherwise not able to provide informed consent. Intoxication was defined by an inability to respond to basic questions, responding incoherently, or participant reporting that they were too high to continue. Client participants were compensated $25 cash for their time.

Interviews were conducted in-person in San Francisco during 1 week in November 2022 and lasted approximately 30-60 minutes. They asked participants about their history of drug use, and experiences with harm reduction services, as well as their awareness of, attitudes about, and experiences with various forms of drug checking.

Interviews with both providers and clients were recorded and the audio was then transcribed. After reviewing the transcripts, the research team identified major themes and sub-themes from the interview summaries. Then, a coding scheme was developed based on codes from the interview guide and themes. The interviews were coded using this scheme.

Among the provider participants, there were 2 clinical providers, 4 researchers, and 5 harm reduction service providers. The 2 clinicians were US-based, 3 of the service providers were US-based while 1 was based in Canada, and 3 of the researchers were US-based while 1 was based in both the US and Canada. Among the client participants, 8 identified as men and 5 identified as female. The majority were between the ages of 30 and 49 and identified as White.

There were differences in the extent to which clients reported using drug checking, their attitudes towards it, and how they respond to results

While almost all clients reported that they have had some experience with fentanyl test strips, their attitudes toward them differed. Some expressed concerns that they were difficult to use or were unreliable. Others reported that they rely on them for unique information about what is in their drugs that they would not get otherwise.

Fewer clients had heard of spectrometry. Some were excited and interested in it, while others were concerned about judgements from the community, bystanders calling the police, and being harassed by law enforcement. Among those who have used it, reports were positive, but also included complaints about how often the results indicated there were substances in their drugs other than what they thought they were purchasing.

There were also differences in how clients reported using the results of drug checking. Some reported that they avoided buying drugs that were contaminated with fentanyl. Others reported they did not want to test their drugs because, for instance, they did not want to have to not use the drugs if they were contaminated, especially if they were going to go through withdrawal, and would not be able to return it for a refund.

Providers agreed drug checking can save lives, but questioned its role in behavior change and wide-scale impact

Providers similarly expressed doubt over whether someone would choose not to use drugs based on the results of drug checking. They discussed how drug checking may not lead to individual behavior change that directly prevents overdoses, but that it adds to the array of harm reduction tools available that together can help reduce the risk of overdoses broadly.

Providers also acknowledged that drug checking may save lives, but questioned the impact it might have on preventing overdoses, discussing how it is difficult to prove that prevention efforts have been effective and how the constantly changing drug market may limit the effects of drug checking.

Drug checking provides valuable information, bodily autonomy, and validation

Providers described how people who use drugs have the right to know what they are putting in their bodies, how drug checking can empower people to make informed decisions, and how it can validate people’s experiences using drugs (e.g., confirming their suspicion that the drugs they took had fentanyl in it).

Clients similarly discussed how drug checking is an important tool they can couple with their own intuition and expertise, which allows them to make informed decisions about their drug use (e.g., testing their supply when they suspect there is fentanyl in it). They also described how it is important to know what you are putting into your body and how they care about their health and well-being. Examples that demonstrate decisions were made that prioritize health were given, including the choice not to smoke out of foil since it is not healthy to do so, the decision to reduce marijuana use due to a sensitive respiratory system, and not wanting to “be a statistic” given the risks of the current drug market.

Drug checking as a tool to help naturalistically regulate drug markets

Clients and providers both discussed how drug checking services could serve as a tool to help regulate the drug market and vet sellers, helping to keep people who use drugs safer. For example, if people knew what was in their drugs before buying it, they could hold sellers accountable because people would be empowered to get it elsewhere. In other words, they would be fully informed about what they are purchasing and if their supplier can be trusted.

Clients shared examples of testing drugs in front of the seller and, if using spectrometry, bringing documentation of what the results were, both of which keeps sellers honest. Providers discussed how drug checking could also benefit sellers who get drugs second-hand and do not necessarily know what it is in it, which was echoed by a client who also sells drugs and expressed wanting to know the chemical balance of what he is selling to make sure it is good.

Participants also discussed how verifying the contents of drugs fills a policy gap, since illicit drug use is not legal and therefore not monitored and regulated. Clients equated this to knowing what is in the food we eat, with one client expressing how it is especially important to know what is in the drugs being used because they do not know where they are coming from and who is making them. Providers expressed how drug checking is only necessary “until prohibition goes away” and the supply could be regulated and safe. Additionally, providers discussed how, if drug checking teams made their results publicly available, it could be helpful to inform clinicians and policy makers about what is circulating in the supply, thereby extending benefits to a broader public health surveillance system and allowing clinicians to tailor the care they are providing.

Concerns about the quickly changing drug supply and the need for multiple approaches to harm reduction

Clients and providers both expressed concerns that the drug supply changes so quickly that spectrometry libraries against which results can be compared may not be able to keep up, which can limit the accuracy of the results. One provider also expressed concern that “we’re just throwing yet another technology at a much bigger problem” and discussed the need for multiple approaches to harm reduction (e.g., syringe service programs), as well as the need to address important social determinants of health, such as housing.

The research team explored how clients and providers of drug checking services value and use these services by conducting semi-structured interviews. In sum, clients reported relying on drug checking services frequently and behavior change given positive results, though others expressed concerns about accuracy and ease of use, concerns about law enforcement’s reaction to them, and not being sure the results would prevent them from using, if the drugs were contaminated. Providers similarly shared the uncertainty about how people might use positive results and questioned whether drug checking services would make a wide scale impact but acknowledged that they can save individual lives for those who use them. Both clients and providers expressed that drug checking services offers people who use drugs valuable information about what is in their drugs, which provides bodily autonomy and fills a policy void by providing some regulation that is otherwise absent.

While this was a small study of just 24 participants in one US city (as is the case for many qualitative studies about unique samples and experiences), the results may provide important insights into how clients and providers of drug checking services perceive the operationalization and value of these services. One important theme that emerged from the findings was that, although drug checking services do not always directly lead to the decision to not use drugs, people who use drugs feel they have the right to know what they are consuming. Having this information allows them to make an informed decision about their use, which often involved behavior change in other ways that prevent harms associated with using contaminated drugs. However, pairing drug checking services with other approaches intended to increase their motivation for not using contaminated drugs, such as motivational interviewing, may prevent overdoses.

In addition, because drug checking services are not mainstream in the US and cannot yet reach every person who uses drugs, they cannot yet have a population-level effect on overdose rates. However, they do offer one harm reduction strategy that could be used in combination with other strategies (e.g., syringe services) that together could make a large-scale impact, if legal and offered widely. Accordingly, drug checking services should be considered within the broader framework of harm reduction for a larger impact on preventing overdoses. Despite the potential public health benefits of harm reduction strategies, including drug checking, syringe services, and safe supply initiatives, many of them are not supported by policy in the US, but are legal and mainstream in other countries, such as Europe.

Finally, one provider importantly highlighted that implementing drug checking services without considering the basic needs of humans and social determinants of health (e.g., housing, employment, access to health care) would neglect the larger structural and systemic problems that contribute to drug use disorders and overdoses. Harm reduction services can help to address the problem immediately, which is critically needed amidst the continuing overdose crisis, but structural and systemic changes are needed as well.

While drug checking services are best understood as one of many harm reduction strategies, and larger systemic changes may be needed to make a wide-scale impact on overdose rates, these services empower people who use drugs to make informed decisions about their drug use. People who use drugs may value this information, and in the absence of regulation (e.g., “safe supply” initiatives), would not be able to do so otherwise.

Moran, L., Ondocsin, J., Outram, S., Ciccarone, D., Werb, D., Holm, N., & Arnold, E. A. (2024). How do we understand the value of drug checking as a component of harm reduction services? A qualitative exploration of client and provider perspectives. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(1), 92. doi.: 10.1186/s12954-024-01014-w

l

Drug checking services offer an approach to harm reduction in which people who use drugs can test the chemicals that make up the drugs they intend to use. This can reveal if they contain harmful substances the person may not want to consume, such as fentanyl and xylazine, which can substantially increase risk for overdose. Having this information provides them with the opportunity to not use the drugs if they are contaminated or to take extra precautions if they choose to use them anyway (e.g., not using alone, using smaller amounts of the drug, using the drug more slowly).

One of the most common forms of drug checking resources are fentanyl testing strips. Fentanyl test strips are small, portable strips of paper that can detect fentanyl in very small concentrations. While their portability and accessibility make them especially useful for outreach and street use, their limitation is that they do not provide information on how much fentanyl is present or if other substances are present, only that fentanyl is present. In cases where a person may want to use fentanyl but want to know the concentration of it, or if someone wishes to have the exact breakdown of the substances making up the drugs they want to use, another form of drug checking called spectrometry may be more useful.

Spectrometry often must be performed in a lab setting by a trained technician, making it less accessible to the general public, but can detect the presence and concentrations of a variety of substances within a drug, including other sedatives which can increase risk for overdose. More recently, spectrometry services are being offered at harm reduction centers, such as syringe service programs and overdose prevention centers.

These services have been implemented in Europe, especially in situations where more people may be using recreational drugs (e.g., music festivals). While drug checking services are not as common in the US and Canada as they are in Europe, research suggests that there is strong interest in them among both people who use drugs and harm reduction providers. The researchers in this study explored how clients and providers of drug checking services value and use these services. Such research can help inform the utility of drug checking services, which can help shape policy.

In this qualitative study, the research team conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with clients and providers of drug checking and harm reduction services to examine the value of such services and how they are operated. The interviews were conducted virtually and in-person in San Francisco in 2022.

Providers included 11 people who provided direct clinical and harm reduction services to people who use drugs, as well as professionals who have expertise with drug checking, such as researchers, who worked in the US and Canada. The researchers recruited providers via email based on their expertise first (i.e., purposive sampling) and then through recommendations (i.e., snowball sampling). Provider participants were compensated $100 for their time.

Interviews with providers were conducted using the Zoom virtual platform between June and November 2022, with each lasting approximately 45-60 minutes. These interviews assessed their perspectives on the state of the drug market in their area, and the perceived needs of and challenges faced by their clients, as well as their attitudes and experiences with drug checking methods and programs and integrating them into existing services.

Clients included 13 people who use drugs and were receiving harm reduction services at an agency where several different forms of drug checking were offered. Participants were recruited by 2 members of the study team who were interviewers and program staff from 4 harm reduction programs in San Francisco (i.e., convenience sampling). Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years of age and current use of fentanyl, heroin, or methamphetamine. Clients were not eligible however if they were currently intoxicated, or otherwise not able to provide informed consent. Intoxication was defined by an inability to respond to basic questions, responding incoherently, or participant reporting that they were too high to continue. Client participants were compensated $25 cash for their time.

Interviews were conducted in-person in San Francisco during 1 week in November 2022 and lasted approximately 30-60 minutes. They asked participants about their history of drug use, and experiences with harm reduction services, as well as their awareness of, attitudes about, and experiences with various forms of drug checking.

Interviews with both providers and clients were recorded and the audio was then transcribed. After reviewing the transcripts, the research team identified major themes and sub-themes from the interview summaries. Then, a coding scheme was developed based on codes from the interview guide and themes. The interviews were coded using this scheme.

Among the provider participants, there were 2 clinical providers, 4 researchers, and 5 harm reduction service providers. The 2 clinicians were US-based, 3 of the service providers were US-based while 1 was based in Canada, and 3 of the researchers were US-based while 1 was based in both the US and Canada. Among the client participants, 8 identified as men and 5 identified as female. The majority were between the ages of 30 and 49 and identified as White.

There were differences in the extent to which clients reported using drug checking, their attitudes towards it, and how they respond to results

While almost all clients reported that they have had some experience with fentanyl test strips, their attitudes toward them differed. Some expressed concerns that they were difficult to use or were unreliable. Others reported that they rely on them for unique information about what is in their drugs that they would not get otherwise.

Fewer clients had heard of spectrometry. Some were excited and interested in it, while others were concerned about judgements from the community, bystanders calling the police, and being harassed by law enforcement. Among those who have used it, reports were positive, but also included complaints about how often the results indicated there were substances in their drugs other than what they thought they were purchasing.

There were also differences in how clients reported using the results of drug checking. Some reported that they avoided buying drugs that were contaminated with fentanyl. Others reported they did not want to test their drugs because, for instance, they did not want to have to not use the drugs if they were contaminated, especially if they were going to go through withdrawal, and would not be able to return it for a refund.

Providers agreed drug checking can save lives, but questioned its role in behavior change and wide-scale impact

Providers similarly expressed doubt over whether someone would choose not to use drugs based on the results of drug checking. They discussed how drug checking may not lead to individual behavior change that directly prevents overdoses, but that it adds to the array of harm reduction tools available that together can help reduce the risk of overdoses broadly.

Providers also acknowledged that drug checking may save lives, but questioned the impact it might have on preventing overdoses, discussing how it is difficult to prove that prevention efforts have been effective and how the constantly changing drug market may limit the effects of drug checking.

Drug checking provides valuable information, bodily autonomy, and validation

Providers described how people who use drugs have the right to know what they are putting in their bodies, how drug checking can empower people to make informed decisions, and how it can validate people’s experiences using drugs (e.g., confirming their suspicion that the drugs they took had fentanyl in it).

Clients similarly discussed how drug checking is an important tool they can couple with their own intuition and expertise, which allows them to make informed decisions about their drug use (e.g., testing their supply when they suspect there is fentanyl in it). They also described how it is important to know what you are putting into your body and how they care about their health and well-being. Examples that demonstrate decisions were made that prioritize health were given, including the choice not to smoke out of foil since it is not healthy to do so, the decision to reduce marijuana use due to a sensitive respiratory system, and not wanting to “be a statistic” given the risks of the current drug market.

Drug checking as a tool to help naturalistically regulate drug markets

Clients and providers both discussed how drug checking services could serve as a tool to help regulate the drug market and vet sellers, helping to keep people who use drugs safer. For example, if people knew what was in their drugs before buying it, they could hold sellers accountable because people would be empowered to get it elsewhere. In other words, they would be fully informed about what they are purchasing and if their supplier can be trusted.

Clients shared examples of testing drugs in front of the seller and, if using spectrometry, bringing documentation of what the results were, both of which keeps sellers honest. Providers discussed how drug checking could also benefit sellers who get drugs second-hand and do not necessarily know what it is in it, which was echoed by a client who also sells drugs and expressed wanting to know the chemical balance of what he is selling to make sure it is good.

Participants also discussed how verifying the contents of drugs fills a policy gap, since illicit drug use is not legal and therefore not monitored and regulated. Clients equated this to knowing what is in the food we eat, with one client expressing how it is especially important to know what is in the drugs being used because they do not know where they are coming from and who is making them. Providers expressed how drug checking is only necessary “until prohibition goes away” and the supply could be regulated and safe. Additionally, providers discussed how, if drug checking teams made their results publicly available, it could be helpful to inform clinicians and policy makers about what is circulating in the supply, thereby extending benefits to a broader public health surveillance system and allowing clinicians to tailor the care they are providing.

Concerns about the quickly changing drug supply and the need for multiple approaches to harm reduction

Clients and providers both expressed concerns that the drug supply changes so quickly that spectrometry libraries against which results can be compared may not be able to keep up, which can limit the accuracy of the results. One provider also expressed concern that “we’re just throwing yet another technology at a much bigger problem” and discussed the need for multiple approaches to harm reduction (e.g., syringe service programs), as well as the need to address important social determinants of health, such as housing.

The research team explored how clients and providers of drug checking services value and use these services by conducting semi-structured interviews. In sum, clients reported relying on drug checking services frequently and behavior change given positive results, though others expressed concerns about accuracy and ease of use, concerns about law enforcement’s reaction to them, and not being sure the results would prevent them from using, if the drugs were contaminated. Providers similarly shared the uncertainty about how people might use positive results and questioned whether drug checking services would make a wide scale impact but acknowledged that they can save individual lives for those who use them. Both clients and providers expressed that drug checking services offers people who use drugs valuable information about what is in their drugs, which provides bodily autonomy and fills a policy void by providing some regulation that is otherwise absent.

While this was a small study of just 24 participants in one US city (as is the case for many qualitative studies about unique samples and experiences), the results may provide important insights into how clients and providers of drug checking services perceive the operationalization and value of these services. One important theme that emerged from the findings was that, although drug checking services do not always directly lead to the decision to not use drugs, people who use drugs feel they have the right to know what they are consuming. Having this information allows them to make an informed decision about their use, which often involved behavior change in other ways that prevent harms associated with using contaminated drugs. However, pairing drug checking services with other approaches intended to increase their motivation for not using contaminated drugs, such as motivational interviewing, may prevent overdoses.

In addition, because drug checking services are not mainstream in the US and cannot yet reach every person who uses drugs, they cannot yet have a population-level effect on overdose rates. However, they do offer one harm reduction strategy that could be used in combination with other strategies (e.g., syringe services) that together could make a large-scale impact, if legal and offered widely. Accordingly, drug checking services should be considered within the broader framework of harm reduction for a larger impact on preventing overdoses. Despite the potential public health benefits of harm reduction strategies, including drug checking, syringe services, and safe supply initiatives, many of them are not supported by policy in the US, but are legal and mainstream in other countries, such as Europe.

Finally, one provider importantly highlighted that implementing drug checking services without considering the basic needs of humans and social determinants of health (e.g., housing, employment, access to health care) would neglect the larger structural and systemic problems that contribute to drug use disorders and overdoses. Harm reduction services can help to address the problem immediately, which is critically needed amidst the continuing overdose crisis, but structural and systemic changes are needed as well.

While drug checking services are best understood as one of many harm reduction strategies, and larger systemic changes may be needed to make a wide-scale impact on overdose rates, these services empower people who use drugs to make informed decisions about their drug use. People who use drugs may value this information, and in the absence of regulation (e.g., “safe supply” initiatives), would not be able to do so otherwise.

Moran, L., Ondocsin, J., Outram, S., Ciccarone, D., Werb, D., Holm, N., & Arnold, E. A. (2024). How do we understand the value of drug checking as a component of harm reduction services? A qualitative exploration of client and provider perspectives. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(1), 92. doi.: 10.1186/s12954-024-01014-w