Even For Those in Recovery, Alcohol Use Disorder Can Have Long Term Health Consequences

It is well established that having a current alcohol use disorder is a tremendous risk to physical and emotional health.

Might alcohol use disorder have long-term health consequences even after you quit?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Alcohol consumption can cause harm in multiple ways:

- Drinking can lead to alcohol use disorder (e.g., addiction); approximately 12% of drinkers meet criteria for alcohol use disorder.

- Alcohol intoxication, of course, by itself can also produce harms such as alcohol-related violence and car crashes and other accidents.

- Alcohol also causes toxicity-related effects in the brain, the heart and cardiovascular system, and in digestive organs such as in the liver.

- It is also a known carcinogen increasing risk of cancer of the breast (in women), as well as throat, voice box, esophagus, and colon.

These physical harms and risks can persist for several years, even after an individual has stopped drinking or no longer has an alcohol use disorder.

While clinical guidelines recommend asking about current drinking, a history of problem drinking might also be important to know in terms of health risks. This study investigated whether having a prior alcohol use disorder – in remission for at least 5 years – was related to a series of medical problems in a large, demographically and geographically representative sample in the United States.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The study focused on individuals in sustained remission from alcohol use disorder for 5 years – a period of time that has been shown to mark stable remission, and the reduction of risk for re-developing substance use disorder similar to that of the general population.

Sustained remission: someone once met diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder, and then no longer meets the threshold for the disorder for at least 1 year.

Authors used data from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). They excluded individuals that were 18-29 years old and those that had an active alcohol use disorder, or were in remission but for less than 5 years. They were interested in the relationships between alcohol use disorder that has been in remission for 5+ years (N = 5566) versus no alcohol use disorder history (N = 20,274) on a series of self-reported medical conditions that were “confirmed by a doctor in the past 12 months.”

Possible conditions included:

- diabetes

- high cholesterol

- liver diseases (cirrhosis and any other forms of liver diseases)

- myocardial infarction (i.e., “heart attack”)

- all other heart diseases

- stomach ulcer

- gastritis (inflammation of the stomach)

- arthritis (inflammation of the joints)

The analyses which tested whether remitted alcohol use disorder was related to having these medical conditions adjusted for many other factors that could also be related both to having an alcohol use disorder as well as to one’s medical condition.

These adjusted factors included, for example, other substance use and mental health disorders, and whether one was a current or former smoker. The participants with remitted alcohol use disorder, on average, were in remission for 22 years and had active alcohol use disorder for 7 years.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

First, compared to those who never had an alcohol use disorder, the remitted alcohol use disorder group (which we refer to just as the remitted group) had more drinking days on average (56 vs. 40 days) and a lower percentage of individuals who were abstinent from alcohol in the past year (30 vs. 44%). They were more likely to be current and former smokers, and to have other psychiatric disorders, including other drug use and mood and anxiety disorders during their lifetime.

Regarding medical conditions, the remitted group had increased likelihood of hypertension, diabetes, myocardial infarction, liver diseases, & arthritis in the past year.

While effects were modest – about 1.05 to 1.35 times greater likelihood – the potential health consequences of these conditions make even small increases in the odds of having the condition very meaningful.

Another important set of findings was, just among those in the remitted group, having active alcohol use disorder for a longer period of time (5+ years) was related to increased likelihood of arteriosclerosis (thickening of the blood vessels which can have serious consequences including heart attack), myocardial infarction, other heart disease, and arthritis.

For example, individuals who had alcohol use disorder for 5 or more years were twice as likely to have myocardial infarction in the past year as those who had the disorder for 4 or fewer years.

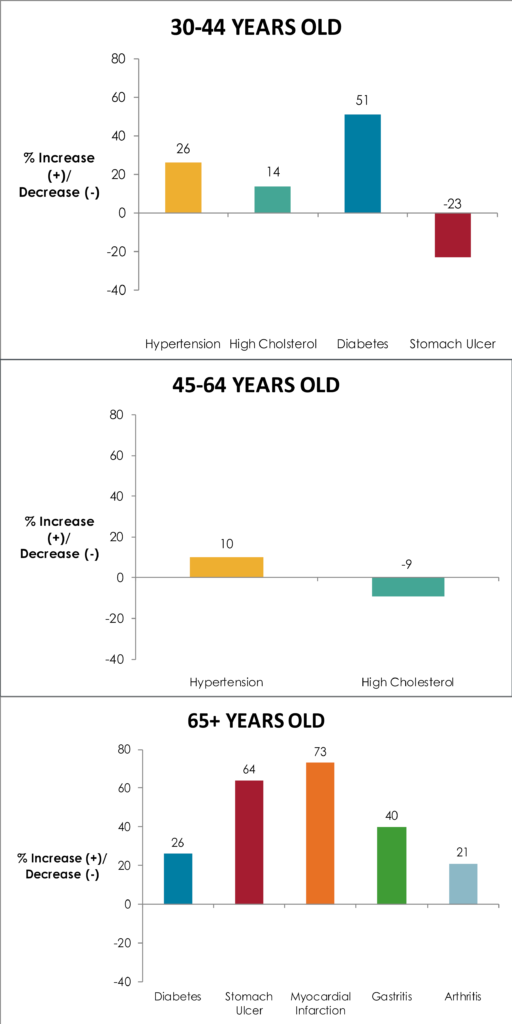

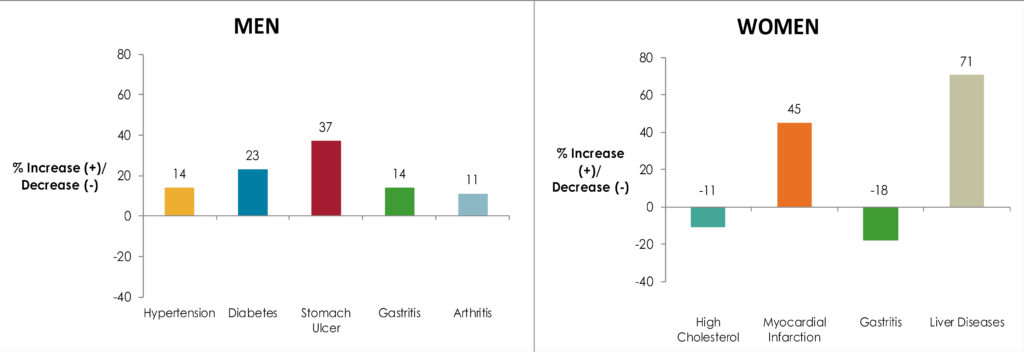

The study authors also looked at relationships between alcohol use disorder history and medical conditions, comparing separately within three different age groups (young – 30 to 44, middle – 45 to 64, and older adults – 65+) and within each gender, to see if history of alcohol use disorder could be a risk factor for different conditions depending on one’s age and/or gender.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT?

This study demonstrates that having a history of alcohol use disorder is related to later ill health.

Doctors should assess not only for current alcohol use, but former use as well, focusing on any lifetime history of problematic use. As one gets older, the risks related to alcohol use disorder could become graver, including heart attack, for example.

Also, what may be most significant to assess is the amount of time lived with an active alcohol use disorder, rather than the mere presence or absence of the disorder, per se. In other words, the sooner one gets into remission the lower the likelihood of developing these conditions during recovery.

The design of the study cannot confirm definitively that it is the person’s history of alcohol use disorder that specifically caused these conditions. Nevertheless, three points are important, to consider:

- study authors adjusted for a host of other possible factors that might have contributed to these conditions (smoking, other drug use disorders)

- more time with alcohol use disorder was related to greater risk for medical problems (i.e., there was a dose-response relationship)

- heavy alcohol use and alcohol use disorder are known to increase one’s chances of disability and death

This suggests it is very plausible – and in fact likely – that participants’ alcohol use disorder history was causally related to onset of these conditions.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The primary limitation is that medical conditions were reported by the participant. As such, the nature of this large-scale survey did not allow validation of the primary outcomes in the study which were determined only by self-report.

NEXT STEPS

Next potential steps include longitudinal studies to understand the causal nature of these relationships. This might optimally occur when medical diagnoses’ presence can be more accurately obtained by researchers or in a health care setting where medical diagnoses can be determined clinically and/or by chart review.

In addition, it may be important to develop and validate a screening questionnaire that adequately captures past history of an alcohol use disorder. In this study, there was an extensive diagnostic questionnaire administered to determine alcohol use disorder history. It would be very helpful to known whether that kind of extensive questionnaire is necessary or whether a shorter one would be sufficient. This strategy might help address the problem while limiting the time burden for medical staff administering the questionnaire.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Even for those whose alcohol use disorder is well behind them, they may still be at increased risk to have medical problems, including diabetes or heart attack. We recommend communicating one’s history of problematic alcohol use to your doctor if you have not already done so. For those seeking recovery, this study suggests that the sooner individuals gets into remission after onset of an alcohol use disorder the lower the likelihood of developing these conditions during recovery.

- For Scientists: This study yields further important information into the long-term health impact of an alcohol use disorder, even when it is in remission. More research is needed to establish temporal precedence between the marker of stable remission used here (e.g., 5 years) and the emergence of health problems. However, in the context of dozens of other studies demonstrating causal relationships between alcohol use and ill health, the study suggests a causal relationship is tenable, if not probable.

- For Policy makers: This study adds further information about the negative health impact of an alcohol use disorder, even when it is in remission. Allocation of funding for research to examine this issue further is likely to add important information about these relationships that could inform primary health care efforts, especially for screening for prior history of alcohol use disorder.

- For Treatment professionals and treatment systems: The results of this study suggest treatment and health care systems should consider evaluating patients not only for current alcohol use, but a history of alcohol use disorder as well. A positive history of alcohol use disorder is related to increased likelihood of several life threatening and/or life impacting medical conditions.

CITATIONS

Udo, T., Vasquez, E., & Shaw, B. A. (2015). A lifetime history of alcohol use disorder increases risk for chronic medical conditions after stable remission. Drug Alcohol Depend, 157, 68-74. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.008