Group Addiction Treatment Program To Reduce Recidivism Rates Among Offenders with Substance Use Disorders

Use of alcohol & other drugs has been linked to criminal justice involvement and may increase the risk of recidivism.

In New South Wales (NSW) Australia, 72% of incarcerated males and 67% of incarcerated females reported that their current offense was related to the use of substances.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Corrective Services New South Wales offers group interventions to address problematic substance use disorder (SUD), promote recovery, and potentially reduce rates of reoffending.

Two main interventions offered by Corrective Services New South Wales are SMART Recovery and Getting SMART. SMART Recovery, based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), consists of 90 minute meetings where participants address four main recovery content areas: motivation to abstain, coping with urges, problem solving skills, and lifestyle balance. Getting SMART, while also CBT-based, was designed by Corrective Services for offenders with significant substance use disorder (SUD) treatment needs who were at high risk of reoffending.

The main goal of Getting SMART is to equip participants with skills needed to transition into SMART Recovery meetings. This is conceptually similar to the use of twelve-step facilitation (TSF) interventions that have been tested to prepare individuals for active participation in 12-step mutual-help groups like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA). Research on SMART Recovery is limited, and interventions to engage individuals in SMART (such as Getting SMART) are needed. Additionally, Getting SMART has not been evaluated alone or in conjunction with SMART Recovery meetings for its ability to impact rates of reoffending.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This quasi-experimental study compared a group of individuals participating in SMART Recovery and/or Getting SMART to a group of control participants matched on various characteristics through the use of propensity scores. This method is used quite often in study designs that are not randomized in order to help determine whether an effect is attributable to the treatment (SMART interventions) or whether it is due to differences that may exist between the two groups (e.g., one is more severe or more motivated than the other to begin with). The authors used databases with details on all offenders in custody between 2007 and 2011 including conviction and reconviction data and details on all entries and exits from custody during this time. The final sample consisted of 3,309 participants who received a SMART intervention and a pool of 13,042 control participants that could be used for matching. Participant pairs who were not matched well enough (i.e., the difference between their propensity scores was too high), were removed from analyses.

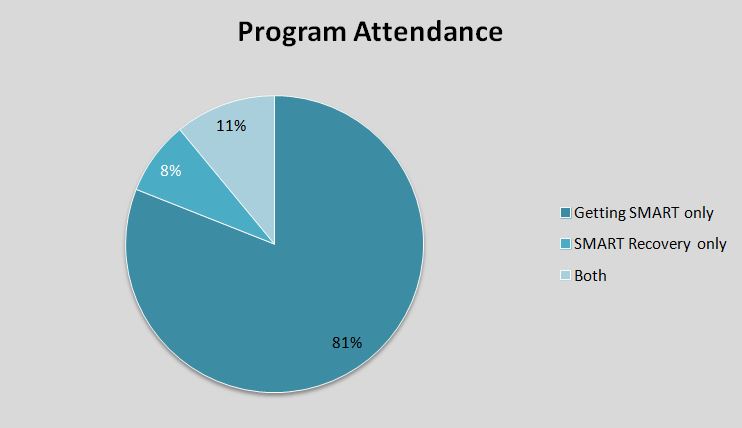

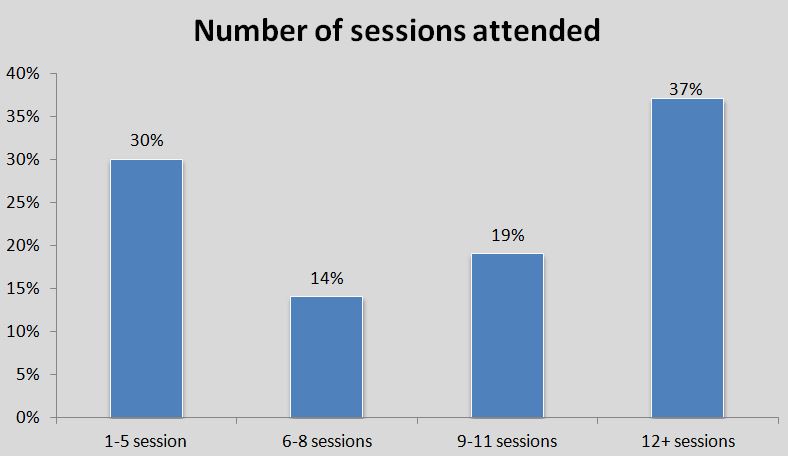

After matching, there was a final sample of 5,764 participants (2,882 SMART participants and 2,882 controls). SMART participants were categorized as attending SMART Recovery, Getting SMART, or both programs. Participants could begin attending SMART recovery meetings at any point during incarceration, and they could attend for as long as they wished. Getting SMART consisted of 12 two hour group session delivered once or twice per week. Completion of the program was defined as attending 10 or more sessions. The authors compared time to first reconviction and reconviction rates between the treated and untreated groups. For the comparison of reconviction rates, they controlled for the amount of time someone could possibly be reconvicted. For example, if they needed to spend time in jail related to a prior charge, this time in jail where they could not commit another crime was controlled for in the analysis. They also compared reconviction rates between participants who attended different amounts of Getting SMART sessions (1-6 sessions, 7-9 sessions, 10-11 sessions, and 12+ sessions).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Participants were mostly male (68%) and considered to be at “medium” (40%) or “medium-high” (27%) risk of reoffending.

The authors found that participating in at least one session of Getting SMART was significantly associated with a longer time to reconviction compared to controls. This was about an 8% reduction in risk of reconviction (i.e., those in Getting SMART remained free of reconviction for 8% longer than controls). The results for SMART Recovery attendance or attendance in both were not statistically significant.

The authors then examined violent reconvictions as an outcome. After adjusting for variables including time free in the community following release (i.e., time during which a person could commit a crime and be reconvicted), Getting SMART participants experienced a 13% longer time to violent reconviction than controls (compared to 8% when examining all types of reconvictions). As with general reconvictions, the results for SMART Recovery only and Getting SMART plus SMART Recovery were not significant.

Lastly, participation in Getting SMART and Getting SMART plus SMART Recovery was associated with a reduced overall rate of reconviction. Rates of reconviction were reduced by 19 and 22%, respectively. For violent reconvictions, rates were reduced by 30% for Getting SMART participation and 42%for Getting SMART plus SMART Recovery. A therapeutic effect was observed after 10-11 SMART sessions were completed such that the rate of reconviction was reduced by 25% compared to controls. Similarities between the treatment and control groups for those attending 1-6 sessions suggest that brief exposure to this intervention may not provide an effect.

This study suggests that participating in Getting SMART can reduce time to first reconviction and reduce rates of reconviction. It also suggests that Getting SMART and SMART recovery together can have an even greater impact as rates of reconviction were reduced more dramatically for the group that received both interventions

While not designed to address violent behavior, the results for violent reconvictions showed greater improvements than what was observed when examining all types of reconviction. For example, Getting SMART participants experienced a 13% longer time to violent reconviction than controls compared to 8% when examining all types of reconvictions. Similarly, the rates of reconviction for Getting SMART participants were reduced by 19 percent for all types of reconviction and 30 percent for violent reconvictions.

The author suggest that the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) principles from these programs may lead to better judgment; while this was intended for decisions concerning problematic use of substance use disorder (SUD), it may also allow individuals to exert greater control in other domains such as violent behavior and crime. Alternatively, the reduced effect on violent behavior/crime may have occurred through reduced substance use and greater abstinence since substance use itself can dis-inhibit people and impair judgment.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Individuals with substance use disorder (SUD) may benefit from ongoing participation in community mutual-help meetings during and after treatment.

While there are many types of mutual-help organizations, 12-step mutual-help (AA, NA) have received the bulk of the attention from researchers and clinical programs.

Research on other mutual-help options such as SMART is needed to inform clinical recommendations especially for those who are resistant or refuse to attend 12-step meetings. Because there has been rapid adoption of SMART and Getting SMART in the NSW prison system, this offers an opportunity to study naturalistically the impact of SMART approaches on criminal justice outcomes. Overall, since Corrective Services aims to use evidence-based interventions for people with addictions, research is needed to determine if Getting SMART—which has yet to be evaluated— is an effective group treatment option.

This study suggests that there is a synergistic effect of the two SMART programs; participating in Getting SMART and then transitioning in to SMART Recovery can reduce rates of reconviction, especially violent reconviction, and can also extend time until reconviction. The authors also note a therapeutic effect after 10-11 sessions which suggests that brief exposure to this intervention may not be adequate to obtain these benefits.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Study participants were not randomized to conditions which makes it more difficult to determine whether the differences are due to SMART or something else that differed between groups. However, given that both programs were already in place, it was not possible to randomize participants since they had access to both interventions. The authors helped address this limitation by using propensity score matching.

- This study did not provide evidence for SMART’s effectiveness at addressing substance use disorder (SUD)-related outcomes.

NEXT STEPS

Potential next steps include replicating the results in a different geographical location such as prisons in the United States. Using a randomized controlled trial design would provide further confidence in the benefit of Getting SMART and Getting SMART plus SMART Recovery.

More research is also needed to determine the optimal time for incarcerated individuals to receive these interventions as it is not known if it is more beneficial to receive this treatment earlier on in a sentence or closer to the release date.

More research is also needed to determine the effectiveness at these programs at addressing substance use-related outcomes.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: While this study did not focus on alcohol or drug-related outcomes, criminal justice involvement is a problem that is strongly correlated with use of substance use disorders (SUD). If used while incarcerated, Getting SMART and/or SMART Recovery may help reduce your risk of being re-convicted upon release.

- For scientists: More research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these programs at reducing substance use following release from prison. A randomized controlled trial of Getting SMART and SMART Recovery participation is also warranted.

- For policy makers: It is important that evidence-based options are available for incarcerated individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). SMART Recovery is a free community recovery resource. This study provides support for the utility of Getting SMART and SMART Recovery at reducing rates of recidivism and reconviction. A cost-effectiveness analysis can determine if such interventions are cost-saving for society.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Resolving issues such as criminal justice involvement are an important part of recovery. Getting SMART and SMART Recovery meeting attendance while incarcerated may be a potential method of overcoming these problems and preventing future arrests.

CITATIONS

Blatch, C., O’Sullivan, K., Delaney, J. J., & Rathbone, D. (2016). Getting SMART, SMART Recovery© programs and reoffending. The Journal of Forensic Practice, 18(1), 3-16. doi:doi:10.1108/JFP-02-2015-0018