Heroin use disorder: A chronic and relapsing condition for most, but a self-limiting condition for a few

Illicit heroin and fentanyl are driving the opioid overdose epidemic in the United States, and heroin use disorder has been characterized as a chronic, relapsing condition. Thus, a better understanding of the natural history of heroin users is vital to inform policy interventions and treatment recommendations. In this study, authors examined the relationships between patterns of heroin use and treatment utilization over a 10-year period.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Studies have shown that that the mortality rate is up to 20 times higher for those with heroin use disorder compared with the general population and that, for those that survive, most will persistently use opioids long-term. In addition, individuals who remain in treatment for longer periods of time have better outcomes. It is also known that there is considerable variability (i.e., heterogeneity) in opioid use trajectories. However, little is known about the joint trajectories of heroin use and treatment utilization among those with heroin use disorder. This study aimed to identify different groups of heroin users based on patterns of both heroin use and treatment utilization, then examined characteristics that predicted classification into each group. Information from this type of analysis could be used to better understand different long-term trajectories of heroin users, potentially informing when and what types of treatments are most appropriate for targeting different goals (e.g., short-term stabilization, long-term health and wellness, etc.). Such information would also help inform local and national policies, as well as clinical treatment guidelines.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used a naturalistic, longitudinal design that followed 428 people with severe heroin use disorder (measured as meeting DSM-IV criteria for heroin dependence) over a period of 10-11 years, first identifying groups based on joint trajectories of heroin use and treatment utilization, then examining which individual characteristics predicted group membership. The study was conducted in Sydney, Australia and authors analyzed data from the initial cohort of 615 individuals enrolled through different treatment modalities: 201 individuals were enrolled from methadone or buprenorphine (often prescribed in combination with naloxone, and known by its brand name Suboxone) pharmacotherapy, 201 individuals were enrolled from opioid detoxification, and 133 individuals were enrolled from residential rehabilitation, as well as 80 non-treatment seekers enrolled through a syringe service program. Participants were randomly selected within each treatment modality and came from a wide range of facilities (18) in the area. The participants used in this study, 70% of the original sample, consisted of those who had complete heroin use and treatment data throughout the study period and were willing and able to be interviewed 10-11 years following study entry. The participants in this study were broadly representative of the initial cohort.

Baseline data was collected in 2001-2002 through a structured interview and included demographic characteristics, past month drug use, professional treatment history, criminal involvement, and history of mental health conditions. The same data points were collected 10-11 years later through a structured interview in addition to the number of times the participants had begun treatment for heroin use disorder in each treatment modality, the recency and duration of each episode, and periods of one or more months of abstinence for each year of the study. Authors used a “life chart” approach to aid memory recall over the 10-year period, which anchors interview questions to significant events in the participants’ lives. A sophisticated statistical technique (four-stage group-based trajectory modeling approach) was used to group the participants based on heroin use and treatment utilization over the 10-11-year period. Next, baseline characteristics were assessed as potential predictors for group membership. Lastly, outcomes at the end of the study and their relationship to group membership were examined. Results on the trajectories of heroin use alone have been published in a preceding study.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

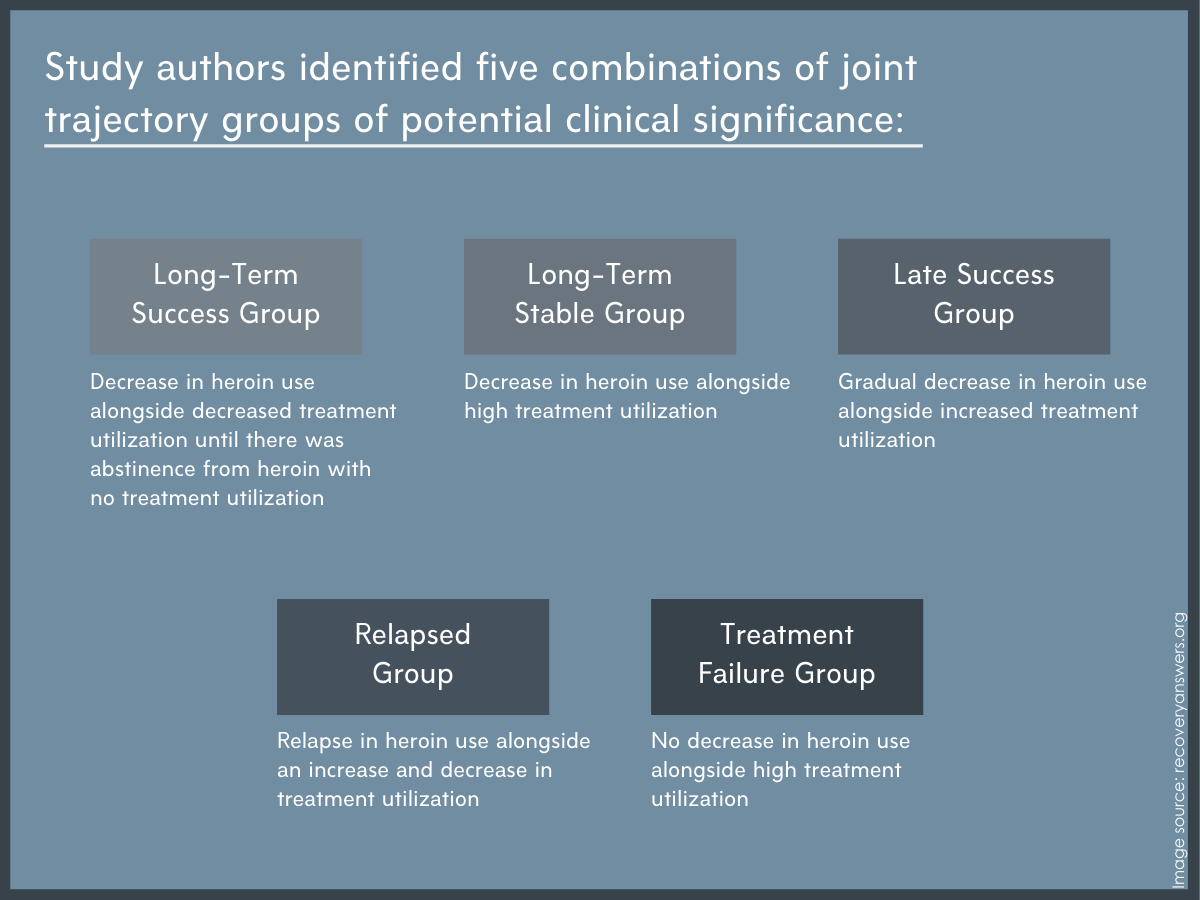

Authors identified five combinations of join trajectory groups of potential clinical significance.

Modeling the separate trajectories for heroin use (six groups) and treatment utilizations (four groups) resulted in 24 joint heroin use and treatment trajectory groups. Based on probability of joint group membership and potential clinical relevance, five combinations of joint trajectory groups were generated by the authors, which comprised 60% of the total sample: 57 were in the ‘Long-Term Success Group’ (13%), 74 were in the ‘Long-Term Stable Group’ (17%), 31 were in the ‘Late Success Group’ (9%), 32 were in the ‘Relapsed Group’ (9%), and 50 were in the ‘Treatment Failure Group’ (12%).

Figure 1.

Treatment utilization included maintenance opioid agonist therapy, residential rehabilitation, and detoxification. Those in the Long-Term Success Group spent the least amount of time in treatment relative to the other groups, were significantly less likely to have been engaged with opioid agonist therapy at baseline compared to the Long-Term Stable Group and the Treatment Failure Group, and were significantly more likely to have entered residential rehabilitation than the Long-Term Stable Group. The Long-Term Stable Group spent more time in opioid agonist treatment than both the Relapsed Group and the Long-Term Success Group. Also, individuals who were in residential rehabilitation at baseline had high probabilities of ending up in both the Long-Term Success Group and the Relapsed Group.

Very few individual characteristics predicted group membership.

Examination of predictors for group membership across baseline demographics, drug use history, or physical or mental health functioning did not help in differentiating who is more likely to be in the Long-Term Success Group, or who is likely to fall into the Treatment Failure Group. At the end of the study period, those in the Long-Term Success Group were more likely than any other group to report wages as the main source of income and were less likely to be involved in past-month crime than the Relapsed Group.

Joint trajectory groups were very different based on drug use and treatment outcomes at the end of the study period.

As expected, drug use and treatment outcomes were very different among the five groups at the end of the study period. No one in the Long-Term Success Group reported heroin use disorder, while the Treatment Failure Group was more likely to report using heroin than all the other groups. The Long-Term Success Group was less likely to report benzodiazepine use than all the groups except the Relapsed Group. The Treatment Failure Group was more likely to report polysubstance use than the Long-Term Success Group and more likely to report injection-related consequences than the Long-Term Success or the Long-Term Stable Group. With regard to treatment, those in the Long-Term Success Group were less likely to currently be in treatment compared with all the other groups. One finding worth particular mention was that the Late Success Group was more likely to have experienced trauma during the study period than the Long-Term Success Group.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study identified 24 joint trajectories of heroin use and treatment utilization over a 10-11 year period, and the authors selected combinations of these trajectories to form five groups based on clinical relevance and probability of joint group membership.

The Long-Term Success Group had a sharp decrease in both heroin use and treatment near the beginning of the study period followed by heroin abstinence and no treatment. The Long-Term Stable Group had a decrease in heroin use alongside high treatment. The Late Success Group had a gradual decrease in heroin use over the study period with a late increase in treatment. The Relapsed Group had a relapse during the study period alongside either a reduction or late increase in treatment. The Treatment Failure group had no decrease in heroin use and high treatment during the entire study period. There were no baseline characteristics that predicted group membership other than those in the Long-Term Success Group were significantly less likely to have been in opioid agonist therapy at baseline compared to the Long-Term Stable Group and the Treatment Failure Group, and significantly more likely to have entered residential rehabilitation than the Long-Term Stable Group.

This study provided a rare insight into the long-term joint trajectories of heroin use and treatment utilization for participants with heroin use disorder. The analysis revealed high variation in trajectories, but a promising finding is that 13% of the participants achieved heroin abstinence without the need for ongoing treatment (Long-Term Success Group) and 17% of the participants achieved a decrease in heroin use in conjunction with high treatment utilization (Long-Term Stable Group). Meanwhile, 12% of the participants exhibited heroin use throughout the study period with high treatment utilization (Treatment Failure Group).

The authors highlight the complexity of the relationship between treatment utilization and favorable outcomes. The implications of these findings are that intervening treatment should be individually tailored and people with heroin use disorder may recover in different ways. For instance, a minority of people with heroin use disorder may benefit from an initial episode of treatment in residential rehabilitation and experience long-term abstinence without the need for ongoing clinical care. Another subset may do well on long-term opioid agonist therapy with methadone or Suboxone. However, some people with heroin use disorder may be seemingly treatment-resistant despite long durations of treatment and may benefit primarily from engagement in harm reduction strategies. In addition, different treatment options may carry different sets of risks and potential benefits. For example, in those who started in residential treatment, the two most common trajectories were Long-Term Success and Relapse; indeed, such an approach may be especially helpful for some but especially risky for others. For most, especially among the Relapsed Group and the Late Success Group, ongoing treatment with relapse prevention and assertive follow-up is imperative to intervene early when recurrence in use occurs. This is especially true since individual characteristics upon entering treatment, such as demographics, drug use history, and physical and mental health factors, are unlikely to predict what is the likely trajectory of heroin use disorder and what should be the best mix of treatment and supportive services.

Given the oftentimes chronic and uncertain nature of heroin use disorder, delivery of ongoing services and maintaining close contact with individuals through recovery management check-ups may be a cost-effective intervention that can enhance long-term recovery outcomes.

Another important finding is that, while the Long-Term Success Group reported heroin abstinence, nearly a quarter of this group reported the use of other opioids, over half reported the use of alcohol, and more than 60% reported the use of multiple drugs in the past month. While abstinence from all substances may be the best pathway to wellness for some, these data are consistent with the National Recovery Study which shows that for United States adults who resolved a problem, about half continue to use alcohol or other drugs. More research is needed to draw definitive conclusions from this finding.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Recall bias is the most important limitation of this study. Even though measures were used to decrease this bias, it would be difficult for a participant to accurately recall drug use and treatment history over a period of a decade or more in the level of detail requested.

- The authors combined some of the 24 joint trajectory groups to form selected combinations that were of clinical interest, although they are not explicit on how this was done. These joint trajectory groups used to form the combined groups may not be representative of each other in terms of heroin use and treatment utilization.

- All the selected combined joint trajectory groups had small sample sizes. This made it difficult statistically for the authors to be able to detect differences between the groups (i.e., statistical power) for both the model that predicts trajectories of heroin use and treatment utilization as well as the model that identifies associated individual characteristics. It is possible that there were other meaningful differences between the five groups that were not identified.

- The rate at which participants drop out of the study over time (i.e., attrition) can be problematic in a longitudinal study because those who drop out of the study may be very different from those that remain in the study, leading to bias of the results.

- Measurement of treatment utilization only included professional treatment services. Thus, engagement in mutual help organizations and other non-professional recovery support services were not captured, which may not represent an accurate description of recovery engagement for many participants in the study.

- Caution should be taken in generalizing these findings, as this study was done in one city in Australia and may not be representative of other treatment systems in the United States.

- The study relied almost exclusively on self-report data, which can introduce bias in the results especially in the context of substance use.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study identified five important groups of people with heroin use disorder who had different long-term trajectories based on heroin use and treatment utilization. There was much variation in the trajectories, with 13% achieving heroin abstinence without the need for ongoing treatment, 17% achieving decreased heroin use with long-term treatment, and 12% not responding to treatment. There was no clear set of characteristics at the beginning of the study that predicted group membership. These findings suggest that most people with heroin use disorder who enter treatment will exhibit a chronic and relapsing condition, while others may exhibit a self-limiting condition without the need for ongoing care. With no clear way of telling what type of trajectory a person will have, continued treatment attempts coupled with ongoing monitoring as well as engagement with harm reduction strategies during periods of heroin use offer the best course of action.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study identified five clinically important groups of people with heroin use disorder (HUD) who had different long-term trajectories based on heroin use and treatment utilization. There was much variation in the trajectories, with 13% achieving heroin abstinence without the need for ongoing treatment, 17% achieving decreased heroin use with long-term treatment, and 12% not responding to treatment. There was no clear set of characteristics at the beginning of the study that predicted group membership. As most groups eventually make gains with ongoing treatment, these findings highlight the benefit of patient-centered treatment engagement as well as the need for diverse treatment modalities that are individually tailored and may include harm reduction strategies. Early detection of those who are not responsive to treatment and are at high risk for recurrence of use is crucial. Therefore, relapse prevention and long-term follow-up with assertive linkage to care as needed may be good techniques for early intervention in these patients.

- For scientists: This study used a four-stage group-based trajectory modeling approach to identify 24 joint trajectories based on both heroin use and treatment utilization over a 10-11 year period. The authors selected combinations of these trajectories to form five groups based on clinical relevance and probability of joint group membership. There was much variation in the trajectories, with 13% achieving heroin abstinence without the need for ongoing treatment, 17% achieving decreased heroin use with long-term treatment, and 12% not responding to treatment. There was no clear set of characteristics at the beginning of the study that predicted group membership. Although these findings should be interpreted within the context of the study limitations, they reveal important areas for future research, such as the phenomenon of natural recovery, further exploration of a seemingly treatment-resistant population, and how life-changing events affect these trajectories (e.g. nonfatal overdose, incarceration, traumatic events). Also, baseline characteristics unmeasured in this study may be predictive of these joint trajectories, such as genetic variability, intensity of heroin use at baseline, and route of administration.

- For policy makers: This study identified five important groups of people with heroin use disorder who had different long-term trajectories based on heroin use and treatment utilization. There was much variation in the trajectories, with 13% achieving heroin abstinence without the need for ongoing treatment, 17% achieving decreased heroin use with long-term treatment, and 12% not responding to treatment. There was no clear set of characteristics at the beginning of the study that predicted group membership. These findings suggest that people with heroin use disorder recover in many different ways, highlighting the need to support many different types of treatment including methadone and buprenorphine therapy. Also, due to the finding that this is a chronic and relapsing condition for most who enter treatment, supporting harm reduction strategies is vital to population health. Finally, many people with heroin use disorder will experience multiple episodes of treatment sometimes followed by recurrence of use, so policies that support reengagement in treatment rather than punishment for recurrent use (e.g., criminal justice consequences) are paramount.

CITATIONS

Marel, C., Mills, K. L., Slade, T., Darke, S., Ross, J., Teesson, M. (2019). Modelling long-term joint trajectories of heroin use and treatment utilisation: Findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study. EClinicalMedicine, 14, 71-79. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.07.013