How Effective Are Recovery Support Services Provided By Other People in Recovery?

Recovery support services often provided by peers also in recovery are emerging in the United States to meet the ongoing, and often complex, needs of individuals with substance use disorder.

This study reviewed the best quality science to date on the effectiveness of recovery support services.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

For many, substance use disorders are chronic conditions with several life-impacting consequences. Even after an initial treatment episode, the risk for relapse often remains high. This risk typically persists up to 5 years after initiating abstinence.

Also, an individual’s social and work lives can still be negatively affected by their substance use disorder for years, and require ongoing support in order to help the person sustain abstinence, and improve their quality of life. For those with substance use disorder, “recovery” is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence with a simultaneous emphasis on enhanced quality of life. Several types of formal services have emerged to support individuals’ recovery efforts and to help them access resources that sustain recovery, also called recovery capital.

These services are separate from informal recovery support through mutual-help organizations, like Alcoholics Anonymous. Examples include peer recovery coaching, recovery housing, recovery community organizations/centers, and collegiate recovery programs. In this study, Bassuk and colleagues conducted a systematic review of the scientific literature on recovery support services.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Study authors searched databases of scientific articles for relevant research published between 1998 and 2014. To be included, studies needed to measure outcomes (rather than simply describe an intervention), and either follow a group over time and/or compare two groups. Studies measuring a single group at one point in time (e.g., cross-sectional) were excluded, as were those with fewer than 50 participants.

The quality of each study was determined to be “strong”, “moderate”, or “weak” in terms of the rigor of its study methods using criteria outlined by the Effective Public Health Practice Project.

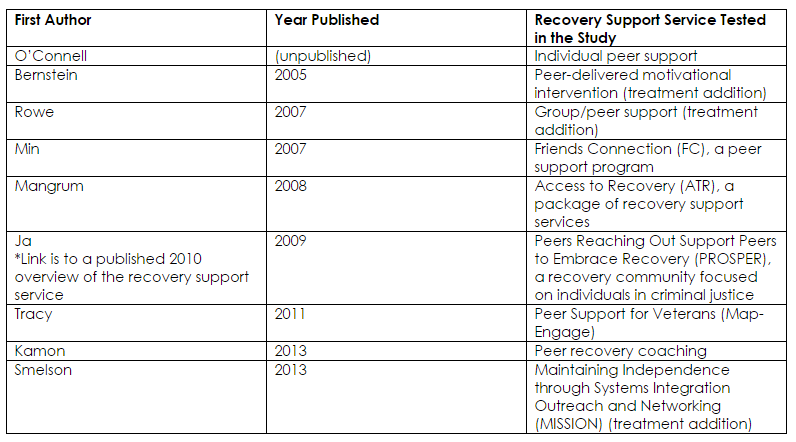

After a rigorous vetting process, authors determined that nine studies would be included in the review.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Links to Source Abstracts: (Bernstein, 2005), (Rowe, 2007), (Min, 2007), (Mangrum, 2008), (Ja, 2010), (Tracy, 2011), (Kamon, 2013), (Smelson, 2013).

Overall, the studies varied considerably in terms of several different characteristics. They ranged from 52 participants to 4,420, and all were focused on adults, many of which had complex clinical presentations, such as severe emotional difficulties in addition to their substance use problem or disorder. The settings where studies were conducted also varied, ranging from community-based settings to clinical ones (e.g., outpatient medical clinic).

Regarding the recovery support services themselves, some provided only a brief 1-session intervention while others tested recovery support over several months or even several years. While many evaluated substance use, this was not the case for all of the studies reviewed. Several assessed treatment utilization, recovery capital, and criminal justice status.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Despite these differences, the review showed there was a meaningful advantage for individuals who received recovery support services. Individuals who received recovery support services improved from their initial levels of substance use and also improved in comparison to those who did not receive such services.

Two randomized trials with “strong”methods were mentioned specifically:

In one, a motivational interviewing intervention delivered by a peer in recovery, added to standard outpatient treatment, promoted higher rates of abstinence compared to outpatient treatment alone.

In the second, individuals with co-occurring substance use, psychiatric disorders, and criminal justice histories who received a peer support intervention in addition to standard clinical treatment had better alcohol, but similar drug outcomes 12 months later.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT?

This study reviewed the small, but growing scientific literature in the area of peer led recovery support services. Peer-led recovery support services are increasingly available, & are being more commonly utilized by individuals with substance use & mental health disorders.

It is critical to know whether peer-led recovery support services work, how they work, and for whom they work best.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Of the nine reviewed studies, only two were considered “strong” in terms of their scientific rigor.

- Also, as authors pointed out, many of the studies lacked detailed descriptions of the actual recovery support services and the specific roles filled by the peer “specialists.” This raises some uncertainty about how well the studies truly tested the effectiveness of these recovery support services, and even more, exactly what services were being tested. More research is certainly warranted, and needed to add to this important body of science.

- NEXT STEPS

-

While randomized controlled trials are not always feasible in real-world settings (e.g., because the services are readily available and even those not randomized to receive the service can easily access it), there are strategies to use sophisticated statistics that help us draw firmer conclusions even when randomization isn’t possible. Future studies may use these more sophisticated statistical approaches (e.g., propensity score matching) to improve methodological quality.

Also, because recovery is understood as an ongoing lifestyle by many, rather than an acute change process, more long-term studies are needed.

Finally, the largest potential advantage of recovery support services is that they cost very little in comparison to traditional clinical services – or perhaps cost nothing at all. Future studies should test the cost-effectiveness of these recovery support services; how much do they cost to deliver, and how much do they save the individual and society potentially through reduced abstinence, less health care utilization, and reduced harms to society.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: While a scientific review such as this one does not lend itself to making specific recommendations, the take home message was that peer-led recovery support services may be a helpful addition to traditional professional services. More research is needed to make definitive recommendations. Based on what we know so far from the science in this area, recovery support services are likely to help you.

- For Scientists: The overall message is that on the studies conducted to date, recovery support service adjuncts appear to be helpful over and above treatment alone. Only two of the nine studies reviewed were considered strong methodologically. Despite its limitations, the review suggests peer recovery support services are promising interventions for individuals with substance use disorder and warrant further investigation including cost-effectiveness studies.

- For Policy makers: Based on the studies conducted to date focused on recovery support services, the overall message is that they appear to be helpful over and above treatment alone. There are relatively few studies that have been conducted, however, and more research is both needed and warranted. Given the tremendous harms to society caused by substance use disorder – even for individuals who seek formal treatment – this study suggests more funding for recovery support service research and program evaluation should be considered.

- For Treatment professionals and treatment systems: Community-based 12-step groups are popular referral options for clinicians, and may be part of a comprehensive, evidence-based plan. This review suggests more formal recovery support services may also be helpful clinical referral resources that enhance your patients’ outcomes. The science in this area is still in early stages, however, and more research is needed. Based on the existing research, recovery support services are likely to help.

CITATIONS

Bassuk, E. L., Hanson, J., Greene, R. N., Richard, M., &Laudet, A. (2016). Peer-Delivered Recovery Support Services for Addictions in the United States: A Systematic Review. J Subst Abuse Treat, 63, 1-9. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.003