How is Addiction Treatment Funded in Other Countries? A Closer Look at Australia

In the U.S., every $1 invested in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment saves society $12 in reduced crime, health care costs, and enhanced productivity.

Australia’s treatment system has much in common with the United States in terms of being funded by both government and private health care support. However, there has been very little research on how treatment programs receive financial support, and whether these funding pathways are strengths or weakness regarding impact on treatment delivery.

Describing funding pathways in Australia might also serve as a model for doing so in other countries.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

For example, past studies show that if a program has several ways it receives funding, it can provide service in a more stable manner because decreases from one source may be minor in the overall funding pool or even offset by increases from other funding sources. One drawback may be that each of these funding sources has different goals or priorities regarding how the funds are used (e.g., what services are offered) with unclear impact on patient outcomes.

Outlining how programs receive financial support in Australia could help improve the efficiency of the funding and offer opportunities to study the impact of funding on patient outcomes.

In this study, Chalmers and colleagues from the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre in Australia interviewed people involved with the funding and delivery of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment to help diagram how money makes its way through the system and the advantages and disadvantages of the flow of funding as it currently exists.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors of this study had three primary goals:

- 1) To illustrate the variety of sources of addiction treatment financing in Australia

- 2) To identify the paths by which funds flow from the initial source to the addiction treatment providers

- 3) To identify any intermediate steps in these funding paths.

Study procedures occurred in three stages:

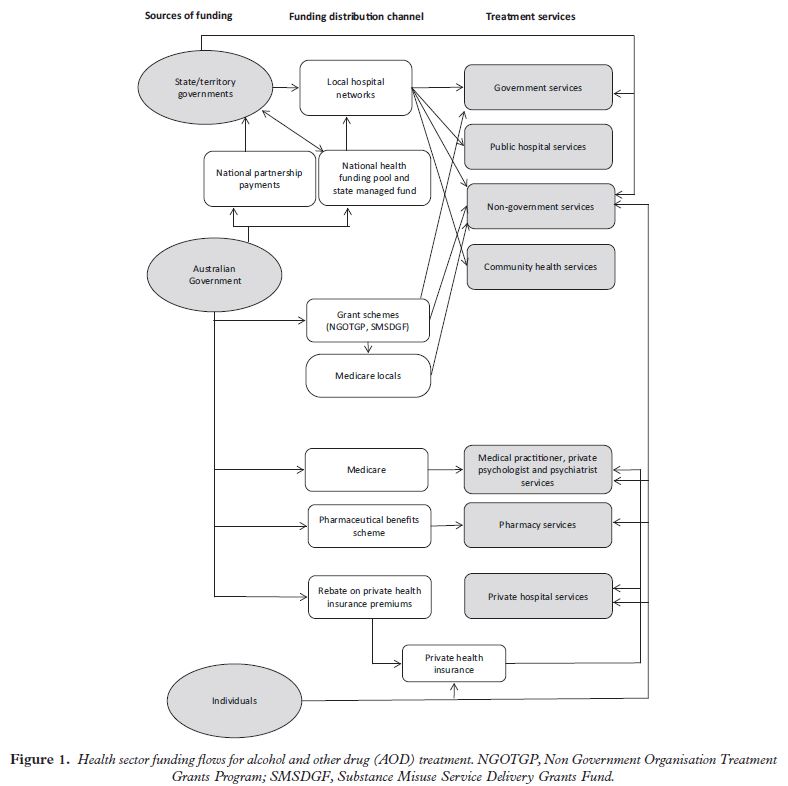

- First, authors searched the scientific literature and Australian government grant program websites to develop a draft diagram of the substance use disorder (SUD) treatment funding stream, from initial funding source to eventual delivery of care.

- Second, they conducted interviews with 190 individuals who had direct knowledge of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment funding and service delivery, including health department employees, treatment staff, and “peak body” organizations that provide SUD service oversight (like the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in the United States, for example). Interviews were conducted either individually or in groups of 3 to 10 people.

- Interviews covered the following topics:

- services and funding

- service types

- how they address and respond to treatment program needs

- funding arrangements

- feedback on the draft diagram, and their comments were incorporated in developing the final version.

- Interviews covered the following topics:

- Finally, authors presented two case studies of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs to illustrate two different funding structures.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

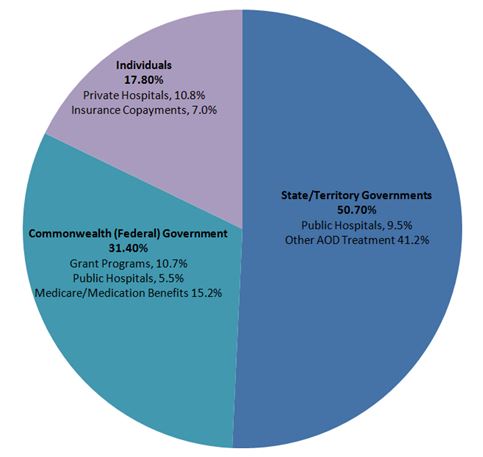

Addiction treatment cost approximately $1.2 billion in 2012-2013.

The diagram shows that the Australian government provides funding to several programs including grant programs, Medicare, pharmaceutical benefits, rebates on private health insurance premiums, as well as collaborations with state/territory government programs.

These state/territory programs fund local hospital networks in addition to their funding collaborations with the Australian government.

Finally, individuals also contribute to the treatment programs by paying private health insurance. Each of these national and state government programs, in addition to individual contributions, fund an array of AOD treatment services, including government and public hospital services, non-government programs, community health programs, medical and psychological support services, and pharmacy and private hospital services.

The qualitative interviews suggested one complication with state/territory funds is that they can sometimes be re-purposed for non substance use disorder (SUD) treatment services if they deem it necessary, though the federal government can sometimes set conditions on how the funds are spent, “earmarking” them for SUD treatment. Also, although not pictured in the diagram, treatment programs may receive support through philanthropy or private fund-raising and may be eligible for certain grant programs if they provide particular kinds of services, such as having a general medical practitioner or psychologist on staff.

The case examples showed that substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs can have very different funding structures. In the first case example, a group of specialty SUD programs received funding from Australian and State governments, patient payments, and outside financial contributions (e.g., philanthropy) for treatment and other recovery support services (e.g., job counseling). In contrast, in the second case example, addiction programs that provided services as part of an overall primary health care and welfare program for marginalized inner city populations received all funding through federal grant programs.

In systems where programs receive funding from multiple sources, it may be difficult to measure the impact of these funds on service delivery and patient outcomes. The delivery of care is often dependent on a number of financial programs, and the impact of any single program can be hard, if not impossible to isolate.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Accurately diagramming how addiction treatment programs receive funding, and how that funding impacts the delivery of services, can help identify potential problem areas to modify and strengths on which to build. This study of Australia’s system could have implications in other countries such as the U.S. where treatment programs are funded both publicly, by Medicare and Medicaid for example, and privately, often with the aid of health insurance companies.

As the authors of this study reported, programs that receive funding from several sources can have a significant administrative burden. Programs may be required to provide updates to the various funding sources on how the funds are being used, and patient outcomes if appropriate.

Staff may be paid from more than one funding source which can become complicated if one of these funding sources becomes unavailable, and when this burden falls upon clinical staff, it can detract from the time spent providing care to patients and potentially hurt patient outcomes.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study was conducted on the Australian substance use disorder (SUD) treatment system and may not apply to other countries. The United Kingdom and Canada, for example, have single-payer, socialized health care systems where the federal government funds all treatment for those who want it supported by resident taxes. These systems stand in contrast to systems in Australia and the United States which, as described above, have a range of public and private funding sources.

NEXT STEPS

Follow-up qualitative research may be conducted to help identify ways to streamline administrative tasks so that clinical staff are not overburdened.

It will also be critical to develop strategies to measure the impact of funding. Interrupted time series designs, like this one described in a prior Recovery Research Institute article summary on the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (see here), can help estimate the influence a new policy or funding initiative has on patient outcomes.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Depending on where one lives, there are likely many ways that treatment and other recovery support services are being funded. One may wish to ask any prospective service provider about how it is funded and how that funding may impact the care they receive there.

- For scientists: This was a unique study that used qualitative methods to describe the funding streams for addiction treatment in Australia. Studies such as these can help identify strengths and weaknesses in the model for future policy researchers.

- For policy makers: Greater knowledge regarding the impact of funding streams on substance use disorder (SUD) treatment service provision and downstream patient outcomes is likely to inform more efficient and helpful ways of paying for treatment services. More systematic and sensitive measurement is likely to yield important information that can lead to greater efficiencies and may also enhance the quality of care for patients.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Understanding the impact of funding streams and the related administrative burden may reveal barriers and inefficiencies that if remedied could result in more effective service models and enhanced quality of patient care.

CITATIONS

Chalmers, J., Ritter, A., Berends, L., & Lancaster, K. (2015). Following the money: Mapping the sources and funding flows of alcohol and other drug treatment in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, n/a-n/a. doi:10.1111/dar.12337