Improving outcomes among patients on medications for opioid use disorder is challenging, but incentivizing patients may be a path forward

Medications such as buprenorphine are considered first-line treatments for opioid use disorder, though around half of patients discontinue these medications after a year and many continue to use opioids. Innovative strategies are needed to improve outcomes among patients on medications for opioid use disorder. In this study, researchers test a novel clinical intervention that incentivizes patients to adhere to treatment and remain abstinent from opioids.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Opioid overdose deaths continue to increase in the United States and other countries. Medications for opioid use disorder, such as methadone and buprenorphine (typically prescribed in formulation with naloxone and known by the brand name Suboxone), are empirically-supported treatment options that decrease mortality. This mortality reduction is enhanced when medications are continued for 180 days or more. Despite this evidence, studies suggest that around half of patients that initiate these medications are still on them one year later. In addition, many patients continue to use opioids during treatment, with one large study estimating that around 40% of those on buprenorphine treatment are also using non-prescribed opioids. Therefore, innovative clinical interventions are needed to improve treatment retention and other outcomes for patients on medications for opioid use disorder. In this study, researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine the clinical effectiveness of an approach that incentivized patients to adhere to buprenorphine treatment and remain abstinent from opioids. Findings could inform clinical practice on innovative ways to keep people in treatment and opioid-free that are taking opioid use disorder medications, which may ultimately lead to sustained remission from opioid use disorder and improved quality of life.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a randomized controlled trial comparing 70 patients that received a version of buprenorphine treatment that incentivized them to take the medication as prescribed and remain abstinent from opioids (experimental group) with 71 patients that underwent treatment-as-usual (the control group) over a 16-week period in an outpatient setting in the United Arab Emirates. Of note, both groups received incentives, though study participants in the experimental group were presented with a stronger incentive (defined as the number of take-home doses of buprenorphine) compared with the control group.

Historically, buprenorphine treatment in the United Arab Emirates was first offered in 2002 and has only been delivered at one facility in the country (the National Rehabilitation Center in Abu Dhabi). Ten years after it began, new initiation of patients on buprenorphine treatment was terminated due to reports of diversion and non-adherence among current patients. Special permission was granted for patients involved in this study to initiate buprenorphine.

Screening of patients for study eligibility was carried out at intake before admission to the inpatient detoxification unit at the National Rehabilitation Center in the United Arab Emirates. Inclusion criteria for recruited participants were aged 18 and older, voluntarily seeking treatment for opioid use disorder, currently diagnosed with an opioid use disorder, evidence of stable housing, and a resident of the United Arab Emirates. Notable exclusion criteria included involvement in the criminal justice system, history of suicide attempt within the past year, presence of cognitive dysfunction, and concurrent use of high doses of benzodiazepines. Patients first went through an inpatient program where they were initiated and stabilized on buprenorphine. During the inpatient stay, the buprenorphine elimination rate for each patient was calculated so that the appropriate buprenorphine concentration could be estimated. This buprenorphine concentration was used to determine whether patients were taking their buprenorphine as prescribed. After completing the inpatient program, patients transitioned to the outpatient setting where they were either randomized into the experimental group (incentivized adherence and abstinence monitoring) or the control group (treatment-as-usual). Study participants received medication at no charge and did not receive any monetary compensation.

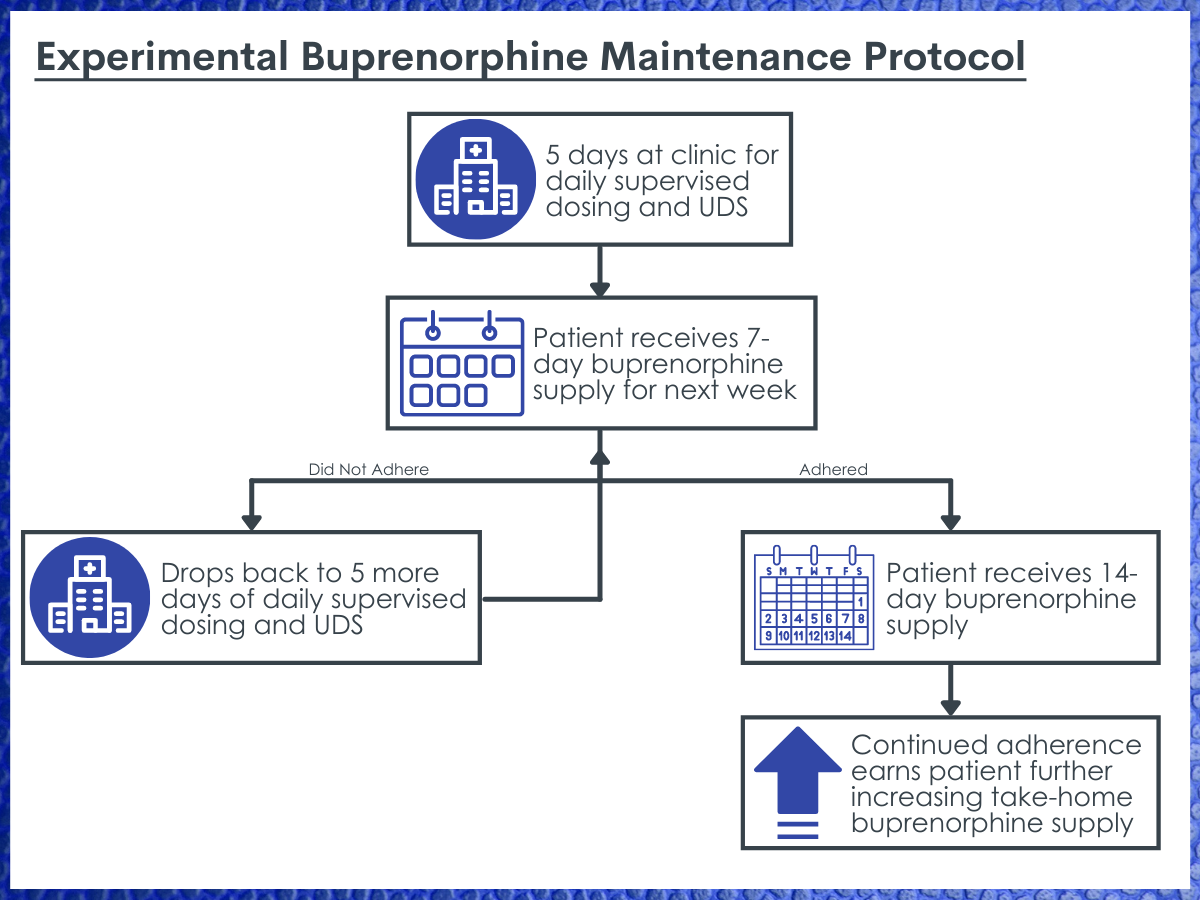

Experimental Protocol: Patients who were randomized to the experimental group attended the outpatient clinic during the first five days for daily supervised dosing and a urine drug screen. If patients adhered (i.e., all doses taken and urine drug screens were positive for buprenorphine and negative for non-prescribed opioids), they were given two doses to take that weekend and a 7-day supply for the next week. If patients came to their next clinic visit one week later and their drug screen was negative for non-prescribed opioids and positive for buprenorphine, they were dispensed a 14-day supply. Patients could earn another 14-day supply if their drug screen was negative and that also had the presence of buprenorphine at their clinic visit two weeks later, where a blood sample was drawn to measure buprenorphine concentration. If patients came to their next clinic visit (14 days later), their urine drug screen was negative for non-prescribed opioids, and their blood sample had a buprenorphine concentration that was in the appropriate range compared to the previous blood sample (within 20%), they were dispensed a 21-day supply and asked to randomly attend the clinic for urine drug screens and blood sampling. On return to the clinic, patients could earn a 28-day supply with continued adherence (blood sample measurement) and abstinence (negative urine drug screens). If patients did not adhere to the protocol at any point during the study period, they dropped back to five consecutive days of supervised dosing until there was evidence of abstinence, upon which patients dropped one level down in receiving a take-home supply of medication (e.g., if a patient was receiving a 21-day supply and was found non-adherent or non-abstinence, he or she would have five days of supervised dosing then receive a 14-day supply).

Experimental buprenorphine maintenance protocol. The researchers utilized a complex experimental buprenorphine maintenance protocol that includes stepwise increases in the patient’s take-home buprenorphine supply as they continue to adhere to the program, and stepwise decreases with supervised dosing and drug screens until they once again reached adherence.

Control Protocol: Patients who were randomized to the control group attended the outpatient clinic at least once in the first five days for supervised dosing and a urine drug screen. If patients adhered to treatment (took all of their doses and had positive urine drug screen for buprenorphine) and remained abstinent (had a negative urine drug screen for opioids), they received a 7-day supply of medication. If patients returned to the clinic one week later and provided evidence of adherence and abstinence, they were given a 14-day supply of medication. If patients did not adhere to the protocol at any point during the study period, they dropped back to five consecutive days of supervised dosing until there was evidence of abstinence. The published study protocol provides more detailed information.

The primary outcome of the study was the percentage of negative drug screens during the 16-week study period. Importantly, non-attendance for a scheduled urine drug screen was recorded as positive for opioids. A secondary outcome of the study was retention in outpatient treatment, defined as completion of 16 weeks of treatment with no more than three missed consecutive clinic appointments. There were also several exploratory outcomes that included scales that measured addiction severity, overall health, anxiety level, impulsivity, and social impairment.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the experimental group and the control group were relatively balanced, meaning that the randomization was somewhat successful at ensuring characteristics were equally represented in the two groups. Notable differences were that the experimental group was more likely to be employed (40% vs. 30%), more likely to live in the Abu Dhabi metro area where the clinic was located (53% vs. 42%), older on average (30.4 years vs. 27.7 years), and had one year longer duration of opioid use disorder on average (9.9 years vs. 8.9 years). There were only two females in the study, resulting in the sample being 98.6% male.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The experimental group was more likely to remain abstinent from opioids compared with the control group.

The percentage of urine drug screens that were negative for opioids was 76.7% among the experimental group and 63.5% among the control group. This meant that the novel clinical intervention resulted in an absolute difference of 13 percentage points, which was statistically significant. When missed appointments were not coded as positive urine drug screens, the percentage point difference increased to 19, likely meaning that the true treatment effect is somewhere in between 13 and 19 percentage points.

Treatment retention in the experimental group and the control group was not statistically different.

Forty study participants (57%) in the experimental group and 33 study participants (46%) in the control group were retained in treatment throughout the 16-week study period, though this difference was not statistically significant. Follow-up rates at 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks, and 16 weeks were 91%, 86%, 71%, and 60% for the experimental group and 85%, 83%, 69%, and 56% for the control group respectively, though those following up at 16 weeks were not considered retained in treatment if they had missed three consecutive clinic appointments or more during the study period.

Very few study participants in the experimental group were able to achieve 21- and 28-day take-home medications.

Only one study participant in the experimental group achieved the maximum number of take-home medication (28 days), meaning that the participant was fully adherent according to therapeutic drug monitoring data and remained abstinent throughout the study period. Only seven study participants in the experimental group (10%) achieved 21 days of take-home medication.

Only one exploratory outcome was different between the experimental and the control group.

At the end of the study, the only exploratory outcome that was statistically significant different between the experimental and the control group was the Work and Social Adjustability Scale, indicating less social impairment associated with opioid use disorder among the experimental group.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This randomized controlled trial found that incentivizing patients in buprenorphine treatment with more take-home medication led to increased abstinence from opioids but did not appear to increase treatment retention compared to treatment-as-usual. Access to more take-home medication was contingent on adhering to treatment (measured by clinic attendance, urine drug screens for buprenorphine, and blood levels of buprenorphine) and remaining abstinent from opioids (measured by urine drug screens for non-prescribed opioids).

Findings from this study offer insight into how clinical protocols can accompany buprenorphine treatment in an outpatient setting to improve patient outcomes. It appears that incentivizing patients with take-home doses of buprenorphine is a promising strategy to increase opioid abstinence. In addition, treatment retention was higher in the experimental group although this difference was not statistically significant. However, the lower-than-expected sample size for this study may not have generated enough power to detect a significant difference. Notably, the difference in take-home days that could be earned between the experimental group and the control group would likely be considered a modest incentive. Indeed, very few patients in the experimental group attained these higher take home dose levels. A stronger incentive, such as one that gave patients a month supply of medications quicker than this study’s protocol, could further improve patient outcomes. Future studies should investigate if stronger incentives have a greater impact on treatment retention and opioid abstinence.

In general, contingency management, which is a type of behavioral therapy in which individuals are rewarded for evidence of positive behavior change, has a strong base of evidence for both directly treating certain types of substance use disorder and as an adjunct to medication or psychosocial treatment. The experimental protocol under examination in this study would be a type of contingency management. In the context of opioid use disorder treatment, adding contingency management to medication treatment is empirically supported. For example, one study using a smartphone app showed that offering monetary incentives for recovery-consistent urine drug screens and treatment attendance for individuals on medication for opioid use disorder increased treatment adherence and opioid abstinence.

There are other promising methods to improve outcomes among individuals on medications for opioid use disorder. Although there is discourse on the additional benefit of adding psychosocial interventions to medication treatment for opioid use disorder, there is evidence that this type of intervention is beneficial to individuals with more challenges, such as continued substance use during treatment. Another innovation that holds promise to improve outcomes, especially treatment retention, for individuals on medications for opioid use disorder is long-acting formulations of buprenorphine, such as a monthly injectable.

The finding that only one study participant in the experimental group achieved a 28-day supply of take-home buprenorphine and only 10% achieved a 21-day supply highlights the challenges of improving outcomes for individuals on medications for opioid use disorder. Other studies suggest that only around half of patients that initiate these medications are still on them one year later, and many patients on buprenorphine treatment continue to use non-prescribed opioids. Studies like this one are important to identify adjuncts to medication that can increase sustained remission from opioid use disorder and improve quality of life

The way that buprenorphine treatment is delivered varies depending on the country. For example, in the United States a patient can begin buprenorphine treatment at a private doctor’s office and receive a monthly prescription without much additional structure. However, methadone (another opioid agonist medication for opioid use disorder) can only be administered at Opioid Treatment Programs where patients are incentivized in much the same way as patients receiving buprenorphine treatment in the United Arab Emirates. Therefore, how these study findings generalize to other countries should be interpreted with caution.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The sample size was small and was 23% smaller than what was calculated at the outset of the study to detect a treatment effect.

- Although randomization seemed to work well when comparing demographics and clinical characteristics of the experimental and the control group, only two females were enrolled in the study. Whether these findings generalize to female identified individuals is unclear.

- This study only examined urine drug screens for opioids and not all illicit drugs or alcohol.

- As mentioned above, due to differences in how opioid use disorder treatment is delivered between the United Arab Emirates and other countries, generalizability of the study findings is limited, especially for the United States where buprenorphine can be initiated in an outpatient setting and is immediately available by monthly prescription in most clinical settings.

- Around half of the study participants did not live close to the outpatient facility, which may have motivated them to achieve more take-home medication, though this was not examined by the researchers.

- The United Arab Emirates discontinued the initiation of buprenorphine treatment in 2012 and only granted initiation of this treatment modality for the purpose of this study. Thus, enrolling in this study was the only way for individuals with opioid use disorder living in this country to begin buprenorphine treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

This randomized controlled trial found that incentivizing patients in buprenorphine treatment with more take-home medication led to increased abstinence from opioids but did not appear to increase treatment retention compared with treatment as usual. Access to more take-home medication was contingent on adhering to treatment, measured by clinic attendance and blood levels of buprenorphine, and remaining abstinent from opioids, measured by urine drug screens. A stronger incentive, such as one that gave patients a month supply of medications quicker than was the case in this study’s protocol, could further improve patient outcomes.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Incentives matter for patients on medications for opioid use disorder. Though not widely integrated into most treatment systems, this and other types of contingency management have been shown to be effective in adjunctively treating opioid use disorder, and individuals and their families may pursue these interventions to support their recovery.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Incentives matter for patients on medications for opioid use disorder. The type of contingency management used in this study, where patients can earn additional take-home medication for providing evidence of adhering to treatment and remaining abstinent, may hold promise in improving patient outcomes, although the context of a country’s treatment system must be taken into consideration. For example, similar incentives are present in the methadone treatment system in the United States, whereas there is much less structure and requirements for buprenorphine treatment.

- For scientists: This single-centered, two-arm, open-label, randomized controlled trial showed a small treatment effect of the novel incentivized adherence and abstinence clinical protocol. The protocol provided a modest incentive to patients, so future research could explore the effect of clinical protocols with stronger incentives. Also, the treatment setting, such as the type of delivery system, and the type of medication for opioid use disorder are likely to impact future research designs. This study only followed patients for 16 weeks. Longer studies that measure a patient’s quality of life and social determinants of health are likely to be fruitful.

- For policy makers: Patients seemed to do better when incentivized to do better. Greater funding for research like this that examines strategies to improve buprenorphine adherence and retention may ultimately maximize outcomes for individuals taking medications for opioid use disorder. Clinical trials measure “efficacy” because they are strictly controlled and usually have short study periods. Therefore, funding studies that can continue to monitor study participants after clinical trials have ended could inform policies and interventions that would increase real-world effectiveness. Natural incentives, such as stable housing and gainful employment that could be accrued during the process of recovery, may be other avenues to improve outcomes among this population.

CITATIONS

Elarabi, H.F., Shawky, M., Mustafa, N., Radwan, D., Elarasheed, A., Yousif Ali, A., Osman, M., Kashmar, A., Al Kathiri, H., Gawad, T., Kodera, A., Al Jneibi, M., Adem, A., Lee, A.J., Marsden, J. (2021) Effectiveness of incentivised adherence and abstinence monitoring in buprenorphine maintenance: A pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Addiction, 116(9), 2398-2408. doi: 10.1111/add.15394