Initiating methadone in jail: Is it cost effective?

Medications for opioid use disorder (e.g., methadone, Suboxone) may be particularly useful in jails and prisons because of their ability to reduce overdose risk after release. However, few studies have looked at the cost-effectiveness of such services, meaning that the benefits and use of services are worth the financial resources needed to provide them. Cost-effectiveness studies help to inform the utility and feasibility of expanding services nationally. In this study, the researchers evaluated the cost and cost-effectiveness of two methadone treatment interventions to produce negative drug tests one year after release. Results showed that methadone treatment provided along with services that facilitate community-based treatment navigation, akin to “recovery coaching”, appear to be the most cost-effective option.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Inmate populations with histories of opioid use disorder are at particularly high risk for opioid-related relapse and overdose after being released from incarceration. Repeated opioid use leads to opioid tolerance (requiring opioid use in larger amounts to feel opioid’s effects) and, upon incarceration, individuals stop using opioids and lose their acquired tolerance to opioid’s effects. Individuals who are released from incarceration and start using a similar amount/dose of opioids as they did before incarceration can overdose due to this loss of tolerance.

To address this increased risk, some criminal justice systems have started offering medication treatments (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine) to inmates with opioid use disorder. These medications are effective at reducing illicit opioid use, risk-taking behaviors (e.g., injection drug use, needle sharing), and overdose rates. However, surprisingly few studies have looked at the cost of providing such services within the criminal justice system and/or the cost-effectiveness of these interventions. Cost-effectiveness studies help determine whether the benefits and use of services are worth the financial resources needed to provide them. Such studies are important to determine their feasibility on a nation-wide scale, as they tell us about the overall impact of policies that implement such interventions, from both public health and financial perspectives. In the current study, researchers examined the cost and cost-effectiveness of two jail-based methadone interventions, compared to no methadone treatment, and their associated community-based healthcare and criminal justice costs 12-months post release from jail.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

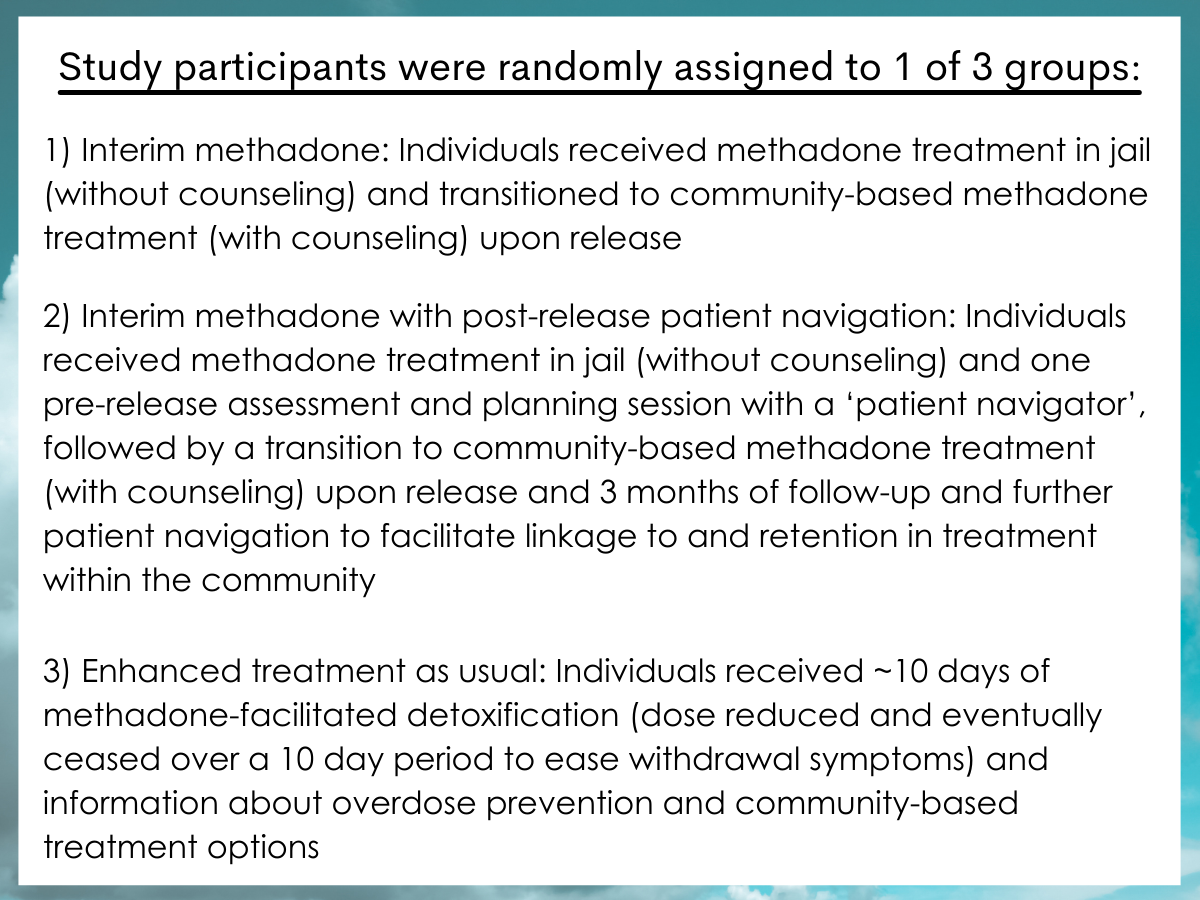

The authors conducted a secondary data analysis of a randomized controlled trial looking at the effectiveness of methadone treatment during incarceration. Two hundred and twenty-five adults who were recently arrested and treated for opioid withdrawal in a Baltimore, Maryland jail were randomly assigned to one of three groups: (1) interim methadone: individuals received methadone treatment in jail (without counseling) and transitioned to community-based methadone treatment (with counseling) upon release; (2) interim methadone with post-release patient navigation: individuals received methadone treatment in jail (without counseling) and one pre-release assessment and planning session with a ‘patient navigator’, followed by a transition to community-based methadone treatment (with counseling) upon release and three months of follow-up and further patient navigation (i.e., practical assistance from a dedicated staff member to help with treatment entry and retention; average of 4 patient navigation sessions) to facilitate linkage to and retention in treatment within the community; (3) enhanced treatment as usual: individuals received ~10 days of methadone-facilitated detoxification (dose reduced and eventually ceased over a 10-day period to ease withdrawal symptoms) and information about overdose prevention and community-based treatment options. Participants completed assessments at baseline (before randomization), and at 3-, 6-, and 12-months following release from jail, which concerned time spent in jail and use of community-based healthcare services.at baseline (before randomization), and at 3-, 6-, and 12-months following release from jail, which concerned time spent in jail and use of community-based healthcare services.

Figure 1.

The interventions’ primary effect of interest was the percentage of participants with an opioid-negative urine drug test at the 12-month follow-up. Individuals who had negative opioid tests, as well as those who had positive opioid tests but were receiving medically prescribed methadone, buprenorphine, and/or prescription opioids, were documented as having a negative urine drug screen. Intervention service logs were used to track methadone dosing while in jail and patient navigation sessions in the community. Structured cost interviews with jail medical staff and study leads informed the resources and funds spent for interim methadone and patient navigation services. Administrative records were used to define the number of times an individual was re-arrested in the 12-months following release from jail.

The authors evaluated the cost of each participant from the time of release to the 12-month follow-up, by identifying the resources used and the unit cost of these resources for each intervention/activity. The unit costs also took into consideration: (1) staff time providing the intervention, (2) staff administrative and travel time, (3) building space, and (4) travel costs.

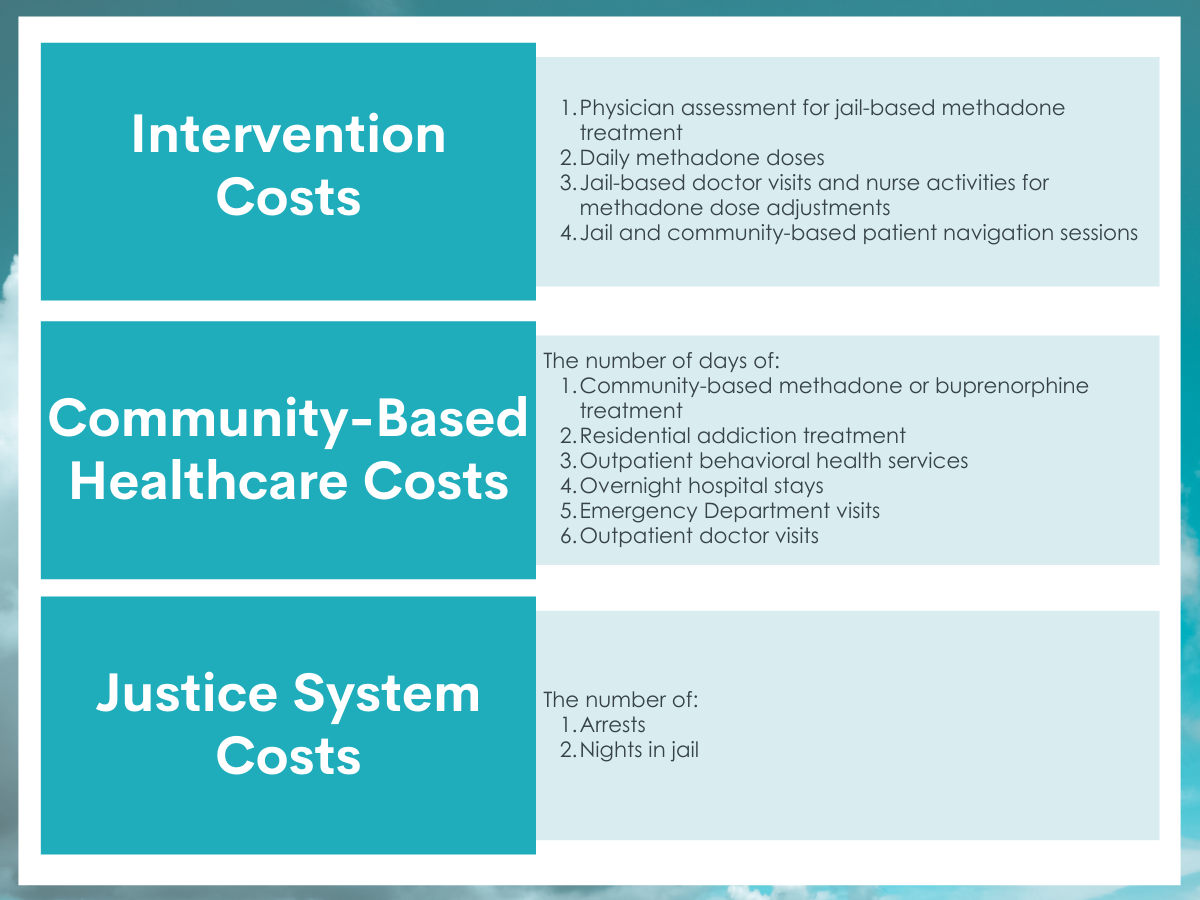

Three cost categories were assessed, including:

Figure 2.

Unit costs for the interventions were actual costs accrued during the study, whereas community healthcare and justice system costs were obtained from the existing literature and inflated to reflect the rate of the 2018 U.S. dollar. Intervention, healthcare, and justice system costs were summed to provide a total cost per participant.

Ratios (i.e., the difference in cost between each intervention, divided by the difference in their ability to produce a negative opioid urine drug test) were calculated to compare the cost-effectiveness of the interventions (i.e., the additional cost of the intervention and associated health care / criminal justice costs necessary to obtain one additional person with a negative test at the 12-month follow-up). All participants who were randomly assigned to a group were included in the analysis as if they received the intervention to which they were originally assigned, (i.e., intent-to-treat analysis).

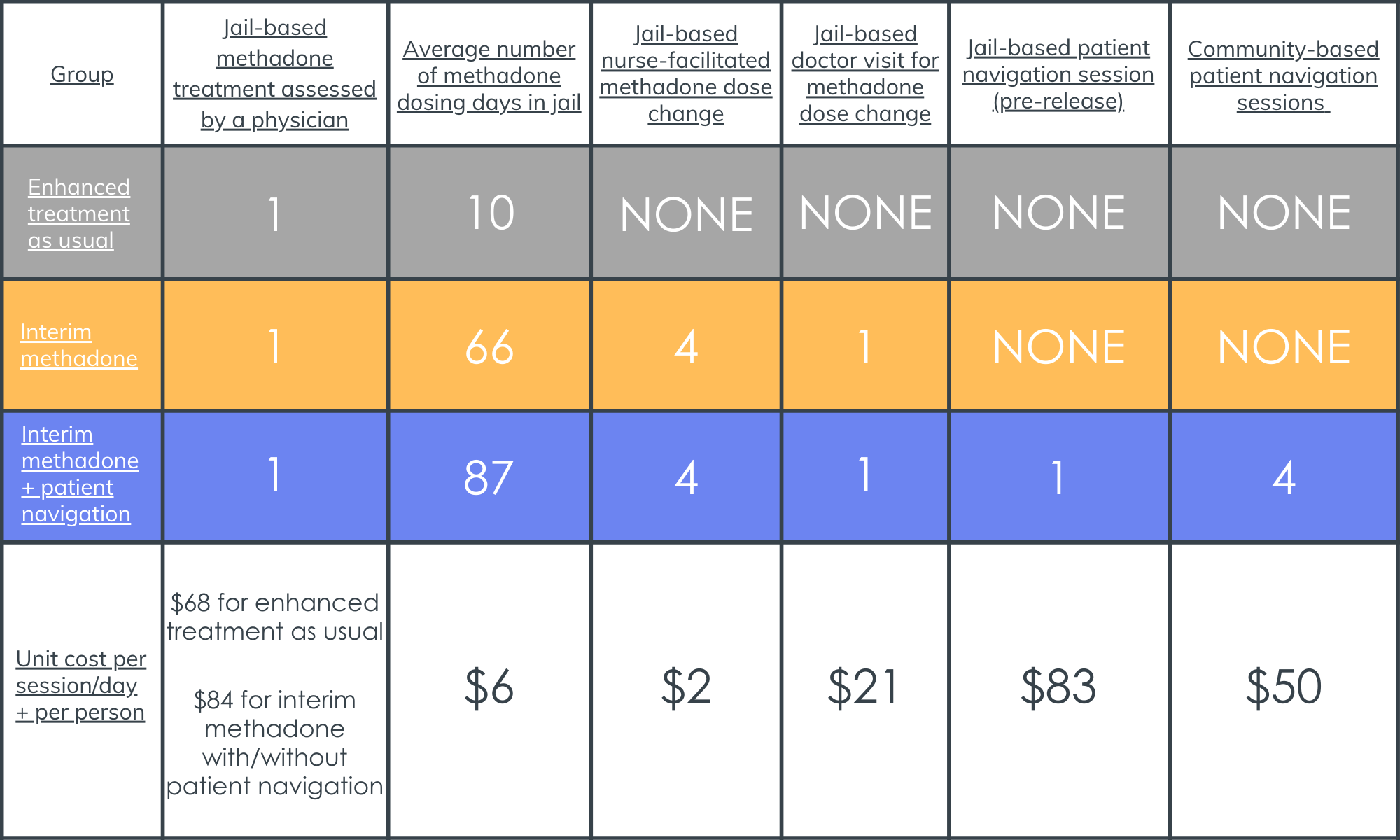

All participants had a diagnosis of OUD (based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth edition), or DSM-5), were in prison for at least two days, and had sentences of one year or less. Nearly two-thirds of participants were Black (62%) with a history of at least one additional arrest in the prior year (63%). Most were men (80%) with an average age of 38 years. The Interim methadone group without patient navigation had fewer total methadone dosing days than the interim methadone group with patient navigation (66 vs. 87 days), which was largely driven by their shorter stay in jail.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The cost and number of times someone used services varied by the type of service and treatment group.

Unit costs were most expensive for physician assessments to start methadone in jail and for patient navigation sessions. Costs were less expensive for methadone dose changes and daily dosing were less expensive.

Figure 3. Shows the number of times each participant utilized each service, according to their group assignment, and the cost of using that service one time (includes staff time and non-labor resources). Note that the interim methadone + patient navigation group received a somewhat higher number of total methadone doses compared to the group receiving interim methadone only, which was driven by the methadone + patient navigation group having a longer average stay in jail.

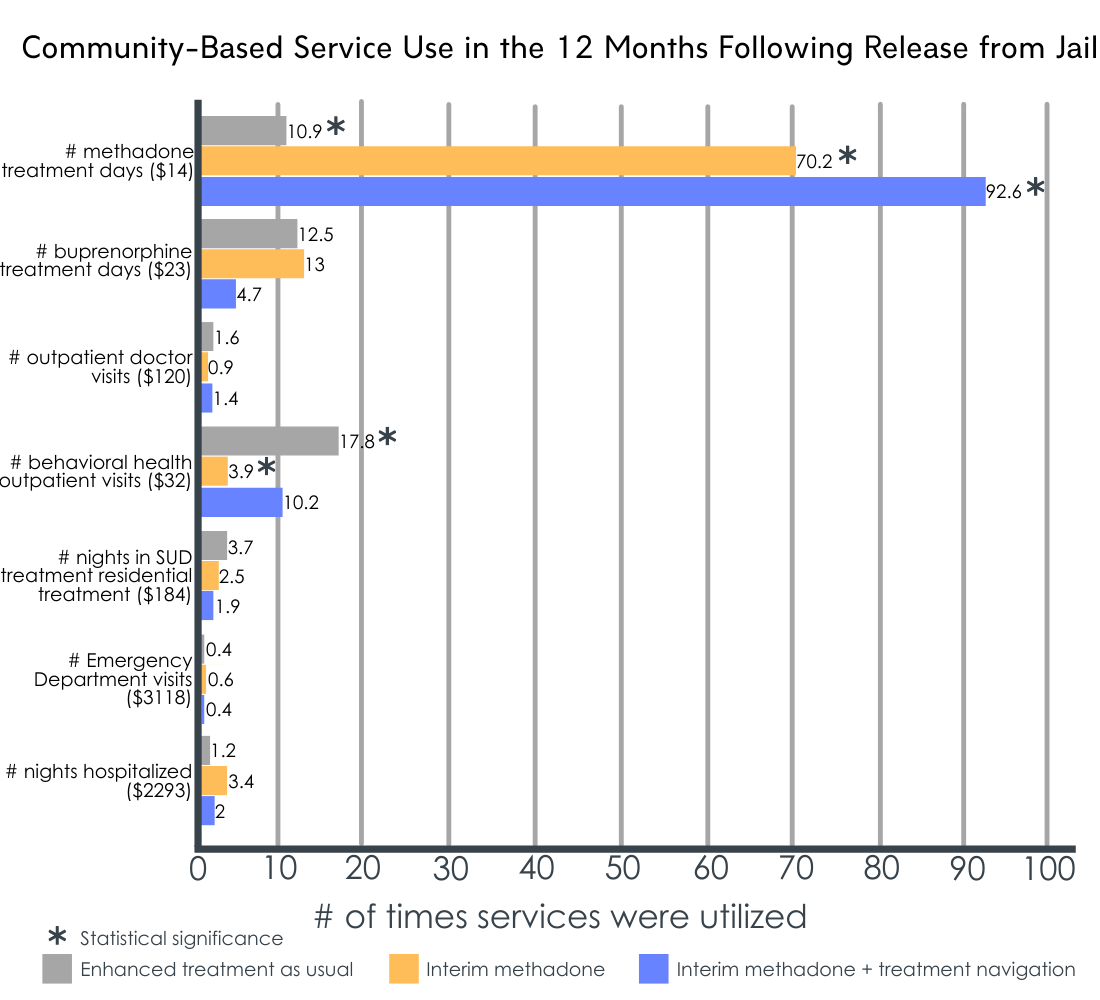

Receiving methadone in jail resulted in more total days of community-based methadone treatment and fewer outpatient behavioral healthcare visits in the 12-month period following release.

Compared to individuals who received enhanced treatment as usual, people who received methadone in jail, alone or in combination with patient navigation, had more days in community-based methadone treatment during the 12 months post release from jail. Individuals who received methadone also had fewer behavioral health outpatient visits at follow-up, compared to those who received enhanced treatment as usual. However, a significant difference was only seen for the interim methadone group without patient navigation. Although groups did not significantly differ in the average number of arrests (Enhanced treatment as usual: 0.88; Interim methadone: 0.86; Interim methadone + patient navigation: 0.63) or nights spent in jail across the entire group (Enhanced treatment as usual: 58; Interim methadone: 46; Interim methadone + patient navigation: 41) over the 12-month follow-up period, the enhanced treatment as usual group exhibited the highest values for these measures.

Figure 4. Depicts the average number of times each group utilized community-based services during the 12 months following release from jail. Dollar amounts on the Y-axis represent the unit cost of a single service use episode. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the enhanced treatment as usual group and one or more of the interim methadone groups.

Total combined intervention, healthcare, and justice system costs did not significantly differ between the intervention groups.

When cost categories were assessed individually, enhanced treatment as usual was less expensive than the two interim methadone interventions, and interim methadone with patient navigation was more expensive than interim methadone alone. The costs associated with criminal justice involvement and with the use of community-based healthcare services (during jail stay and within the 12-months following release) were not significantly different between the three interventions. When assessed as raw dollar values, community-based healthcare costs were highest among individuals who received interim methadone alone (i.e., $11,273; Treatment as usual: $5,212; Interim methadone + patient navigation: $8,200), and criminal justice system costs were highest among individuals in the enhanced treatment as usual group (i.e., $4,661; Interim methadone: $3,907; Interim methadone + patient navigation: $3,363).

The percentage of individuals with a negative opioid urine drug test at 12-month follow-up did not significantly differ between the intervention groups.

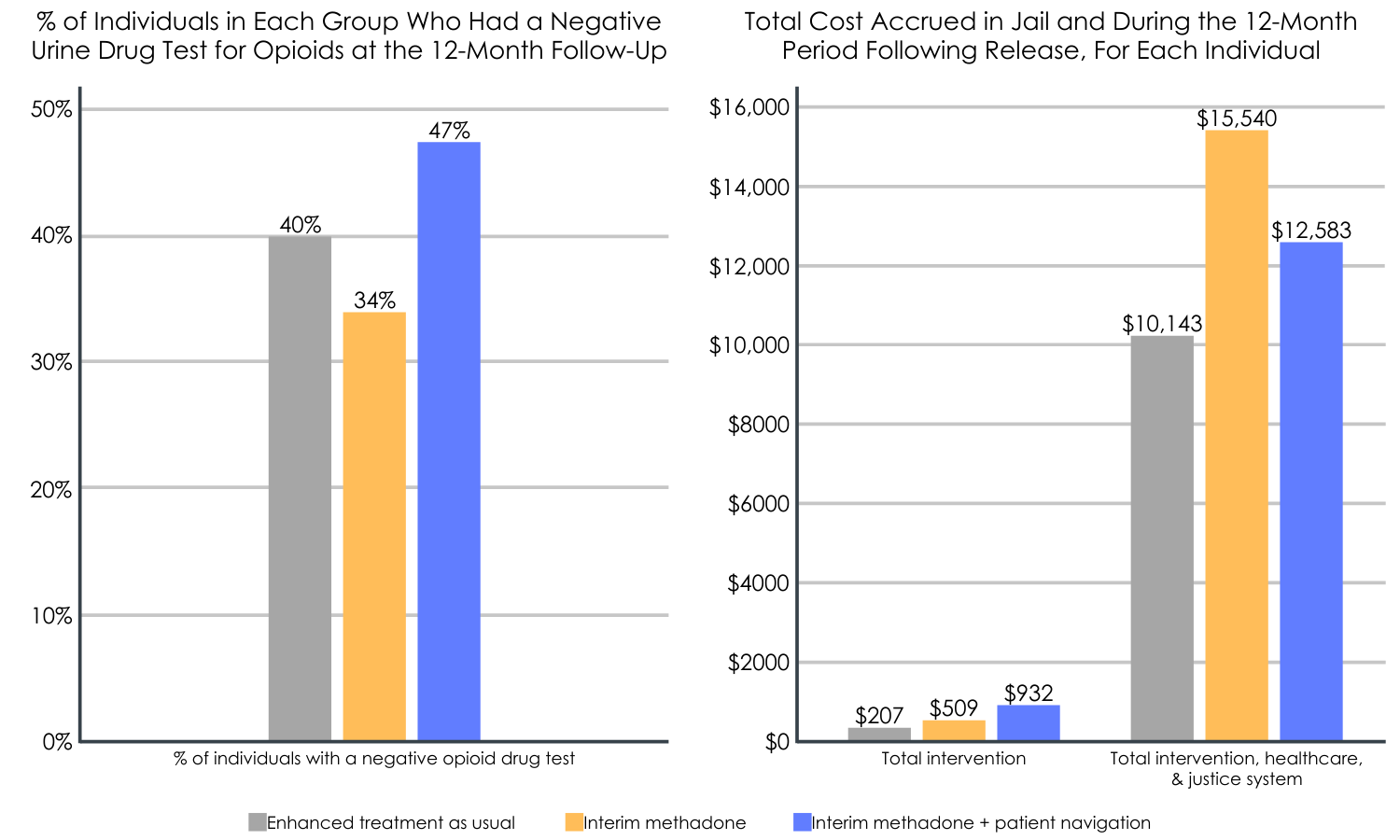

Although no significant differences emerged, as shown in the left side of figure 2, the data indicate that individuals in the interim methadone plus patient navigation intervention group had the highest rates of negative opioid urine tests (47% vs 40% vs 34%).

Figure 5. Left: Predicted percentage of participants with negative urine drug test for opioids at the 12-month follow-up. No significant differences in the negative drug tests were observed between the 3 interventions, but the highest rates were seen for interim methadone + patient navigation. Right: Total predicted intervention costs (alone), and the total combined intervention, healthcare, and justice system costs accrued both in jail and during the 12 months after release. Enhanced treatment as usual was less expensive than the other interventions; interim methadone + patient navigation was more expensive than interim methadone in the total intervention group, but was less expensive in the total intervention, healthcare, & justice system group.

Interim methadone plus patient navigation was the most cost-effective intervention.

When compared to enhanced treatment as usual, interim methadone without patient navigation was 53% more expensive and 15% less effective (fewer individuals testing negative for opioids at month 12). Interim methadone with patient navigation was 24% more expensive but also 18% more effective. In other words, when one considers the costs of providing each intervention alone, interim methadone plus patient navigation is likely to cost substantially more but it produces better opioid abstinence rates. Interim methadone without patient navigation never emerged as the optimal intervention. The enhanced treatment as usual intervention, however, was substantially cheaper than the other treatment intervention options, and had almost as good outcomes as the interim methadone plus patient navigation intervention. Enhanced treatment as usual also had the lowest cost burden in the year following release from jail/prison.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Studies like this help us better understand the utility and feasibility of implementing medication-based OUD treatment in criminal justice settings, which will ultimately inform policy and shed light on whether or not such interventions can be implemented on a national scale.

This study found that interim methadone treatment, together with 3 months of patient navigation to aid an inmate’s navigation of community-based care, is likely to produce the best opioid abstinence rates, though is also likely to cost more across intervention, healthcare, and criminal justice costs during up through the first year after release. Somewhat surprisingly, enhanced treatment as usual did almost as well in terms of opioid use outcomes but cost considerably less to deliver and was associated with lower overall costs in the year following prison release. Interim methadone alone, on the other hand, was not found to be cost effective when compared to enhanced treatment as usual, as it was more expensive and less effective (fewer negative opioid drug tests).

Findings highlight the importance of facilitating treatment transitions from the justice system to the community. Though medication without patient navigation resulted in greater use of community-based methadone treatment and fewer behavioral health outpatient visits upon release (vs. enhanced treatment as usual), the cost of this intervention relative to its relative ineffectiveness in producing negative opioid drug tests one year suggest it was not a cost-effective option. Therefore, from a cost-effectiveness perspective and with regard to opioid abstinence, adding patient navigation following release might be the best option for policy makers and justice systems able to earmark the necessary funding to support individuals with opioid use disorder.

Although methadone with patient navigation was the most expensive intervention, the patient navigation sessions only accounted for 30% of this intervention’s costs, which appear to be driven instead by the higher number of total methadone doses received by this group compared to the methadone only group while incarcerated (i.e., longer stay in jail).

When considering whether to add patient navigation to standard methadone maintenance, results suggest that adding patient navigation to methadone treatment might cost about $400 more than methadone alone initially, but ultimately saves over $2,900 down the road in intervention, healthcare, and justice system costs while also producing better opioid abstinence rates. Given that the opioid crisis cost the U.S. economy $631 billion between 2015 and 2018 alone (one-third attributable to healthcare costs), long term cost savings like these are certainly needed. Therefore, this intervention may be a financially friendly, effective, and feasible option.

Figure 6.

Importantly, the enhanced treatment as usual condition performed quite well and was associated with the lowest overall costs in the year following release. This intervention is not standard across jails and prisons, with relatively few implementing this kind of methadone-facilitated detoxification and providing informational resources regarding overdose prevention and community-based treatment. Therefore, the control group in this study could be considered as receiving a low-threshold intervention and if interim methadone with/without patient navigation was compared to other standard jail procedures (non-supervised or non-assisted withdrawal), their effects may have been more pronounced and/or cost effective. That said, given its own cost-effectiveness utility, and the fact that its outcomes were almost as good as the interim methadone plus patient navigation intervention, this enhanced treatment as usual protocol warrants further investigation for its cost-effectiveness in future studies.

Another important component to remember is that the effect of interest was a negative opioid drug test, and cost-effectiveness may vary across outcomes of interest, like overdose and quality of life. It is also unclear how a negative drug test might translate to downstream cost savings in overdose deaths and infectious disease transmission, for example, requiring additional research. Indeed, studies show that methadone reduces overdose risk when administered in the criminal justice setting, and methadone treatment initiated upon release from the justice system has also shown to be cost effective with regard to preventing overdose death. However, there are relatively few of these cost effectiveness studies in criminal justice settings. Outside of this setting, research has shown the benefits of patient navigation for enhancing treatment engagement after detoxification, and the cost effectiveness of various recovery services that help follow patients over time.

For example, recovery management checkups provide long-term clinical follow-up (e.g., quarterly checkups) to patients with substance use disorder, and are shown to be a cost-effective way to improve long-term recovery outcomes (reduced substance use and related problems). Recovery coaching is another service, similar to the patient navigation assessed in the current study, that is shown to cost-effectively facilitate community-based treatment navigation and is associated with positive changes among individuals who use these services in general healthcare settings (e.g., fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits, higher rates of abstinence & medication treatment retention). Therefore, additional research is needed to evaluate various medication treatment protocols, including patient navigation and similar services that support successful treatment outcomes, to determine the most cost-effective methods in various criminal justice settings.

This study corroborates previous findings of methadone’s benefit in criminal justice settings, revealing that methadone initiation in jail, regardless of its pairing with patient navigation, resulted in greater use of community-based methadone treatment and fewer behavioral health outpatient visits upon release from jail.

Although the community-based healthcare costs were highest among individuals who received interim methadone without patient navigation, this was likely driven by the high number of overnight hospital stays reported by a select few in this group and additional research is needed to reassess this finding. Interestingly, the original randomized controlled trial on which this data was based found that methadone without patient navigation was just as effective as methadone with patient navigation at promoting OUD treatment 30 days after release and producing negative opioid drug tests for up to 12 months. Thus, this study is not saying the methadone treatment alone is not beneficial. Rather, it suggests that adding patient navigation to medication treatment may be a means for enhancing the effectiveness (i.e., negative opioid tests) outward of one year after release, while also saving money, namely via reduced community healthcare and criminal justice system costs.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Treatment as usual was enhanced with a methadone taper and informational resources, which is not standardized across U.S. jail and prison systems. Therefore, the impact of the methadone interventions might be even greater in real world correctional systems/procedures. Cost-effectiveness in this study also focused on 12-month drug screen outcomes and additional work is needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of patient navigation for other patient outcomes, like patient well-being and overdose death.

- Data were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis, which included data from all participants who were randomly assigned, including those who were not released from jail and instead were tapered off of methadone, transferred to prison, and followed up following release from prison. Unit costs were also determined using the scientific literature rather than actual costs incurred and 12-month urine test results were missing for 39 individuals, with predicted instead of actual values used for these participants. Although sensitivity analysis, excluding participants with missing data, suggested similar outcomes, additional research is needed to replicate these findings using complete data sets and actual costs.

- Intervention cost analyses did not account for different lengths of jail time between the three groups. Given that the interim methadone + patient navigation group spent more time in jail, their intervention appeared as if it cost substantially more than the other interventions (due to additional methadone doses received in jail). More research will help determine costs when time in jail is kept consistent. Methadone dose was not reported, and its efficacy can vary by dose. Those receiving community-based opioid treatment at the 12-month follow-up were designated as having a negative urine drug test for opioids. However, it is unclear if the drug tests were sensitive enough to detect specific opioids (e.g., methadone vs. fentanyl) and people could have been misusing opioids on top of their opioid-based treatments, which could impact outcomes.

BOTTOM LINE

Studies like this help us better understand the practicality of executing medication-based OUD treatment in criminal justice settings on a national scale, which will ultimately inform policies and guidelines for helping individuals with OUD at the justice system level. Focusing on methadone, this study found that methadone treatment in jail, along with patient navigation after release from jail was the most cost-effective intervention for producing negative opioid tests 12 months after release. Importantly, methadone produced beneficial outcomes regardless of patient navigation (e.g., more days receiving community-based methadone, fewer behavioral healthcare outpatient visits). However, adding patient navigation to methadone treatment seemed to yield the best effects (greatest proportion of negative urine tests) relative to its intervention, healthcare, and justice system costs. Given the benefits of methadone treatment seen in criminal justice settings, additional research is needed to identify how to get the most bang for the buck when it comes to implementing them on a large scale. Additional cost effectiveness analyses with other outcome measures and in different criminal justice settings will ultimately help determine the feasibility of various interventions and the willingness of policy makers to dedicate funds to these respective treatment protocols.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Individuals who are suffering from OUD and provided with methadone treatment in the context of jail or prison might benefit from family member and healthcare provider assistance in navigating OUD care after release from incarceration, particularly when patient navigation services (like the one reviewed in this study) are not available.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Healthcare systems might consider partnering with the criminal justice system to facilitate inmate transitions to community-based OUD treatment and continued care. Aiding such transitions might ultimately benefit the patient and incur fewer costs for the community healthcare sector.

- For scientists: Additional research is needed to determine the cost-effectiveness of OUD medication treatments in jail/prison, including research addressing effects other than negative drug tests (e.g., quality of life, overdose) and studies in various correctional settings with different infrastructures. There is a significant need for research in this area, as this is one of only a couple of studies that have evaluated such effects.

- For policy makers: These findings suggest that methadone treatment provided in criminal justice systems, combined with post-release patient navigation services, is a potential cost-effective option for promoting illicit opioid abstinence one year after release. Although this intervention was the most expensive, it was also the most effective. Relative to interim methadone alone, methadone plus patient navigation also saved over $2,900 down the road in intervention, healthcare, and justice system costs combined. If policy makers are willing to pay enhanced costs up front, this type of combination medication-recovery support service intervention would almost certainly be the cost-effective choice over time. Additional research funding will help identify cost effectiveness for similar interventions (e.g., buprenorphine) and other outcomes (e.g., overdose deaths, quality of life).

CITATIONS

Zarkin, G. A., Orme, S., Dunlap, L. J., Kelly, S. M., Mitchell, S. G., O’Grady, K. E., & Schwartz, R. P. (2020). Cost and cost-effectiveness of interim methadone treatment and patient navigation initiated in jail. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 217, 108292. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108292