LGBT Treatment Seeking for Alcohol Use Disorder: A Focus On Sexual Minorities

Certain groups of individuals appear to be disproportionately affected by the burdens of alcohol given their prevalence in the general U.S. population.

Individuals identifying as lesbian, gay & bisexual (LGB) appear to be one such group – they are more likely to consume alcohol & to meet criteria for alcohol use disorder (AUD) than heterosexuals.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Allen and Mowbray used a large, nationally representative sample from the National Epidemiological Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) to investigate differences between LGB and heterosexuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) on rates of treatment seeking and perceived barriers to seeking treatment.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The study analyzed 11,182 individuals that completed both waves of the NESARC (2001-2002 & 2004-2005) who met criteria for an alcohol use disorder (AUD) in their lifetime, based on the 4th edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV, which used alcohol “dependence” or “abuse” terminology).

Of these individuals, in response to the question, “Which of these categories describes you?”:

- 2% (n = 182) identified as gay/lesbian

- 1% (n = 126) as bisexual

- 97% (n = 10874) as heterosexual.

This study excluded participants who identified as “not sure.”

The research focused on 15 types of help-seeking for an alcohol problem, including professional (e.g., outpatient or residential treatment) and non-professional (e.g., 12-step mutual-help) services. They also assessed reasons for not seeking help in a subset of 1165 participants (gay/lesbian = 31; bisexual = 22; heterosexual = 1112) who considered, but did not seek, help for their alcohol problem. Researchers tested whether one’s sexual orientation was related to clinical characteristics (e.g., co-occurring psychiatric disorders in addition to alcohol use disorder (AUD), such as generalized anxiety disorder) as well as treatment utilization or barriers to seeking treatment, controlling for other demographic (e.g., gender) and clinical characteristics.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

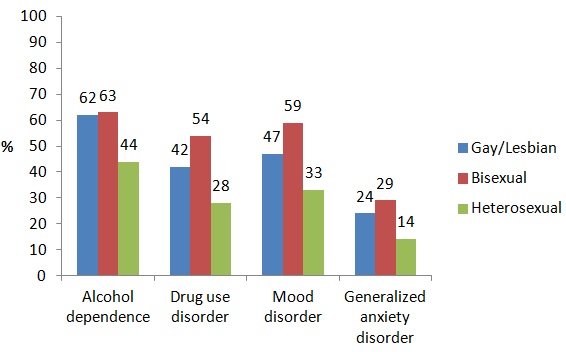

Regarding the relationship between sexual identity and clinical characteristics, sexual minorities were generally more clinically severe than their heterosexual counterparts. Gay/lesbian (G/L) and bisexual (B) individuals were more likely than heterosexual (H) individuals to meet criteria for alcohol dependence (62% vs. 63% vs. 44%, respectively) rather than alcohol abuse and to have a lifetime co-occurring drug use disorder (42% vs. 54% vs. 28%), mood disorder (47% vs. 59% vs. 33%), and generalized anxiety disorder (24% vs. 29% vs. 14%). See figure below. Whether gay/lesbian and bisexual individuals differed from each other on clinical characteristics was not specifically examined.

Bisexual individuals were generally more likely than heterosexuals to seek help for alcohol use disorder (AUD) than heterosexuals both overall and across a range of conditions. They were 2 times more likely to seek help overall, and 2 times more likely to attend 12-step mutual-help meetings, 2.5 times more likely to attend alcohol/drug detoxification, 5.5 times more likely to participate in an employee assistance program, and 2 times more likely to seek help through a private professional’s office (e.g., physician or psychologist).

Gay/lesbian individuals generally had similar rates of treatment seeking compared to heterosexual individuals.

Like treatment seeking, when those who considered but did not seek treatment were assessed specifically, bisexual individuals were generally more likely than both gay/lesbian and heterosexual individuals to endorse several key reasons for not seeking treatment.

Reasons included but were not limited to:

a) “tried getting help before and didn’t work”

b) “thought the problem would get better by itself”

c) “afraid of what boss, friends, family, or others would think”

d) “afraid they would put me in the hospital”

e) “could not afford to pay the bill”

Overall, individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) who identify as bisexual may be more clinically severe – particularly in terms of having co-occurring drug use and psychiatric disorders – than heterosexual individuals, and perhaps relative to gay/lesbian individuals as well. One possibility is that bisexual individuals may feel they do not “fit” socially, or have difficulty finding a long-term romantic partner, within the conventional “gay or straight?” paradigm in the United States, increasing their day-to-day stress.

From a stress and coping theory perspective, this increased stress, in turn, may put a tremendous strain on their coping resources thereby exacerbating, emotional difficulties (e.g., mood disorder) and maladaptive attempts to cope with those difficulties (e.g., drinking and other drug use). Future studies should examine in greater detail why individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) who identify as bisexual appear to be more clinically severe than those who identify as gay/lesbian or heterosexual.

This study also added to previous research showing LGB individuals attend alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment at higher rates, overall, compared to their heterosexual counterparts.

Descriptively, LGB individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to consider, but decide ultimately not to seek, help for their alcohol problem (17% vs. 10%, respectively).

Because bisexual individuals, in particular, were more likely to endorse many reasons for not seeking treatment, there may be opportunities to engage an even greater number of these individuals in addiction treatment and recovery support services. However, because they may voice several reasons that make it difficult for them to attend treatment, they may benefit initially from approaches that help address this ambivalence toward change, such as motivational enhancement therapy.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Like their ethnic minority counterparts, sexual minorities with alcohol use disorder (AUD) may face stigma and discrimination due not only to their problematic alcohol and other drug use, but also to their identity. As such, these minority groups may require special attention in treatment and recovery research to help identify their unique circumstances and, in particular, factors that promote or hinder their engagement in treatment and recovery support services.

LGB, with bisexual individuals in particular, were more likely than heterosexual individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) to endorse a multitude of reasons for not seeking treatment.

While the reasons for bisexual individuals’ negative perceptions about treatment engagement and outcomes are not clear from this study, their ambivalence about reducing or quitting drinking may be even more common than is typically the case among those with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Clinical approaches geared to addressing ambivalence, such as motivational enhancement therapy, may be needed initially before interventions geared toward abstinence, such as cognitive-behavioral and/or 12-step facilitation, are implemented.

LGB individuals, and those identifying as bisexual in particular, may enter treatment with more complicated clinical presentations, including but not limited to greater likelihood of co-occurring drug and psychiatric disorders.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The data used in this study were not intended to specifically investigate the role of sexual identity in treatment engagement. Precise reasons why LGB individuals have higher rates of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and addiction help-seeking compared to heterosexuals cannot be determined from this study. Because this large, representative, survey was conducted in 2004-2005 and participants could only identify as heterosexual, gay/lesbian, bisexual, or “not sure”, more flexible and/or contemporary notions of sexuality (e.g., pansexual, transexual) were not examined.

- In addition, the study assessed one’s sexual identity, but not sexual behavior. These two are not synonymous, while both may have implications for alcohol and other drug use behavior (see here, for example). Thus, results may not generalize if the study was replicated in 2016, and may be different if sexual behavior was considered in addition to sexual identity.

NEXT STEPS

These data were collected well before the supreme court decision allowing same-sex couples to marry, a law that could increase LGB individuals’ access to health insurance through their spouses’ employment. It will be important, therefore, to examine whether these patterns still hold true today, particularly with respect to help seeking and insurance coverage.

Next steps may also include in-depth qualitative interviews with those who identify as gay/lesbian and/or bisexual to better understand their perceived barriers for help seeking, including the possible unique stigmatization they may face as sexual minorities.

Also, this study examined only a history of treatment engagement. It may be important to investigate whether sexual minorities have different rates of treatment completion, or outcomes, compared to their heterosexually identified counterparts.

In addition, there are programs that cater specifically to the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) community (see here). Although studies that investigate these programs generally suggest they may have added benefit for this group of treatment seekers compared to standard addiction treatment programs (see here), these studies collected retrospective data (i.e., participants were asked to think back on their treatment experience). In order to determine whether these LGBT-specific programs are responsible for participants improved outcomes, future studies may investigate whether sexual minorities with alcohol use disorder (AUD) randomized to these specialized programs have higher rates of treatment completion and better alcohol outcomes compared to those randomized to standard addiction treatment programs.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: If one has a problem with alcohol and/or other drug use and identifies as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, one is likely to face more challenges in treatment than your heterosexual counterparts. It may be helpful to tell treatment providers about unique experiences with respect to your sexual identity, alcohol/drug problem, and how the two may be related.

- For scientists: This analysis of an existing, large epidemiological dataset was a well-conducted study of the impact of identifying as a sexual minority on treatment seeking. While rates of treatment seeking are higher among gay/lesbian and bisexual individuals with alcohol use disorder compared to heterosexuals, bisexuals were more likely to endorse several perceived barriers to seeking treatment. Future studies may investigate these barriers, and whether there exists a health disparity (i.e., “preventable difference in the opportunity to achieve optimal health”) related to alcohol use disorder for gay/lesbian and bisexual individuals.

- For policy makers: This study showed that gay/lesbian and bisexual individuals with alcohol use disorder may be more clinically severe and endorse more barriers to engaging in treatment. Consider funding research specifically to enhance gay/lesbian and bisexual individuals’ access to, and engagement, in treatment.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Gay/lesbian and bisexual patients may enter treatment with more complicated clinical presentations. In addition, LGB, and bisexual individuals in particular, were more likely than heterosexual individuals with alcohol use disorder to endorse a multitude of reasons why they did not want to attend treatment. These potentially unique attributes should be considered as part of their assessment and treatment planning, and ambivalence about treatment engagement should be explored very early in the treatment process.