Who’s more likely to be able to get naloxone (Narcan) at their pharmacy? A look at the socioeconomic factors associated with naloxone availability

The current opioid overdose crisis disproportionately impacts urban, socioeconomically marginalized, and minority communities. This is, in part, due to major disparities in access to healthcare resources, including life-saving medications like naloxone (also known and marketed by the brand name Narcan) that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. This study explored socioeconomic factors associated with naloxone availability in pharmacies across New York City.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The ongoing opioid overdose crisis continues to disproportionately impact urban, socioeconomically marginalized and minority communities in the United States. For instance, in New York City, residents located in high poverty neighborhoods have higher rates of non-fatal and fatal overdose compared to residents in wealthier neighborhoods. Though there are numerous, complex, racial and socioeconomic factors that drive these health disparities, one key reason marginalized and minority communities are disproportionality affected by opioid overdose is poorer access to life saving medications like naloxone (a medication best known by the brand name Narcan that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose), and buprenorphine (a medication best known by the brand names Subutex and Suboxone that can support opioid use disorder recovery while also reducing the risk of opioid overdose).

This study specifically focusses on the availability of naloxone at pharmacies throughout New York City, and how certain socioeconomic factors are associated with the likelihood that a pharmacy will carry this important medication. The researchers hypothesized that pharmacies in neighborhoods with greater proportions of racial and ethnic minorities, greater rates of poverty, and higher overdose death rates are less likely to have naloxone in stock. They also predicted that pharmacies participating in the Naloxone Cost Assistance Program—a New York State funded initiative aimed at increasing naloxone access—would be more likely to have naloxone in stock. Studies like this that identify factors associated with worse access to naloxone are critical to informing policies and interventions to address these inequities.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was an observational study surveying 662 pharmacies in New York City that were identified using the publicly available directory of pharmacies participating in the New York City standing-order naloxone initiative – a program that allows individuals to get naloxone from pharmacies without a prescription.

The outcome of interest was whether pharmacies carried naloxone or not. The researchers examined whether the following factors were associated with this outcome: 1) Neighborhood sociodemographic factors, health factors including overdose, and insurance coverage. 2) Neighborhood racial and ethnic composition consisting of the proportion of neighborhood residents who identified as non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, Asian, and other/more than one race. 3) Neighborhood poverty rates including percentage of the residents in each neighborhood whose annual income is less than the current federal poverty line. 4) Neighborhood overdose rates resulting from use of illicit drugs. 5) Pharmacy participation in Naloxone Cost Assistance Program which helps individuals with limited means access this medication. They examined whether these factors, adjusting for pharmacy, community and policy factors were associated with greater or lower likelihood of pharmacies carrying naloxone.

Initially, research assistants conducted phone-interviews with 1151 pharmacies, of which 662 pharmacies consented to participate in the study and completed the survey (57.5 % participation rate). Cited reasons for non-participation included corporate policy, insufficient time, or a general refusal.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The majority of surveyed pharmacies carried naloxone.

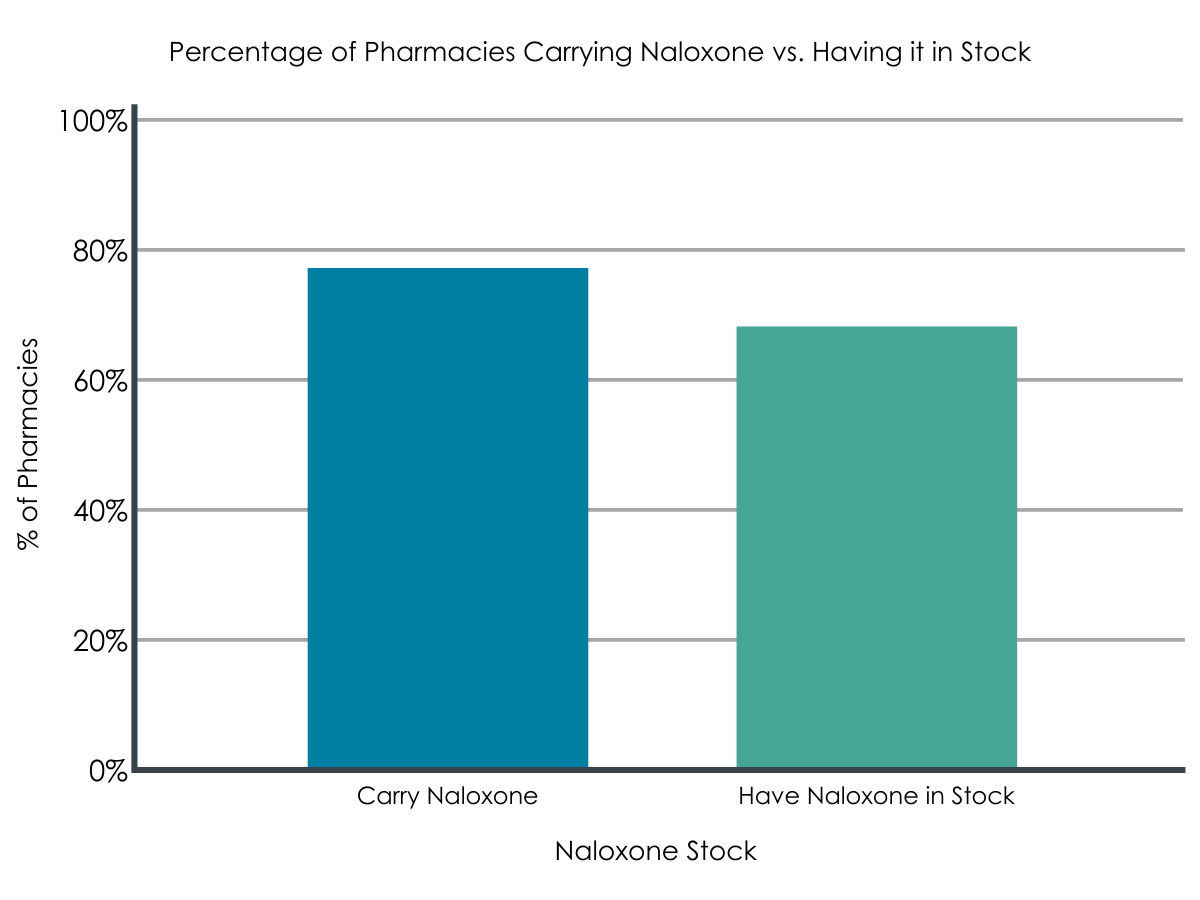

Of the 662 pharmacies surveyed, more than three-quarters reported carrying naloxone (78.37%, n= 511), and approximately two-thirds reported having naloxone in stock at the time of the survey (67.18%, n= 438).

Figure 1. Percentage of pharmacies carrying naloxone vs. having it in stock.

Pharmacies that provided naloxone were more likely to be located in neighborhoods with lower overdose rates.

The mean overdose death rate in New York City at the time of the study was 16.36 deaths per 100,000 (SD= 6.83). As predicted by the researchers, pharmacies that provided naloxone were in communities with significantly lower neighborhood overdose death rates compared to pharmacies that did not provide naloxone (Mean death rates= 15.45 vs. 18.21).

Pharmacies that provided naloxone were less likely to be located in neighborhoods with greater poverty rates.

In line with the researchers’ hypotheses, after statistically controlling for other socioeconomic factors, they found that pharmacies located in neighborhoods with greater rates of poverty were 21% less likely to have naloxone in stock compared to pharmacies in wealthier neighborhoods.

Neighborhood racial make-up was not found to be associated pharmacy naloxone availability.

Contrary to the researchers’ prediction, after statistically controlling for other socioeconomic factors, neither the percentage of Hispanic and African American people nor rates of overdose in a neighborhood were associated with the likelihood of carrying naloxone.

Pharmacies participating in the Naloxone Cost Assistance Program were more likely to carry naloxone.

Pharmacies that participated in the Naloxone Cost Assistance Program were 63% more likely to carry naloxone compared to pharmacies that did not participate in this New York State program.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

In this study, pharmacies were identified using a registry of pharmacies participating in the New York City standing-order naloxone program. Concerningly, around one-fifth of surveyed pharmacies didn’t carry naloxone, and of those that did, a third didn’t currently have naloxone in stock. Additionally, only about half of the pharmacies contacted for the study agreed to participate. It’s possible this gave rise to some self-selection bias with some pharmacies declining participation in the study because they were not carrying the medication and were not inclined to disclose this fact.

Results showed that pharmacies in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty were less likely to offer naloxone compared to pharmacies in wealthier neighborhoods, though notably, after controlling for other factors, the racial makeup of neighborhoods was not associated with whether pharmacies carried naloxone. Because the data used in this study were cross-sectional (i.e., they were collected at a single point in time), it is impossible to disentangle cause and effect relationships between pharmacies carrying naloxone or not, and neighborhood characteristics. That said, the data here provide a snapshot of the relationship between neighborhood factors and the likelihood that pharmacies in that neighborhood will carry naloxone. Of note, areas with higher levels of poverty may need more targeted policies and interventions to increase naloxone availability.

The study’s researchers provide several explanations for their findings. They speculate that pharmacies in disadvantaged neighborhoods may lack the financial resources to hire or train staff to dispense naloxone or be hesitant to stock naloxone due to stigma, negative attitudes about serving customers who use drugs, or fear of increasing crime by being a source of naloxone. Also that pharmacies in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods may experience higher rates of policing leading to fear that providing naloxone would attract unwanted police attention. An alternative explanation could be that people in lower income neighborhoods in New York City are accessing naloxone at rates similar to people in higher income areas, but they are getting their naloxone through different channels such as community naloxone distribution programs, which were not studied in this paper, and are more likely to serve those with limited means.

The finding that pharmacies participating in the Naloxone Cost Assistance Program were more likely to have naloxone in stock than those which did not participate may seem intuitive and unsurprising. However, this result points to the effectiveness of such programs and the value of policies and initiatives that support public health. This also highlights the importance of reducing legal barriers to naloxone.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Pharmacies were identified using a registry of pharmacies participating in the New York City standing-order naloxone program, which likely inflates the observed rate of number of pharmacies carrying naltrexone.

Also, as noted by the researchers:

- The low pharmacy study participation rate may limit generalizability of the study to all pharmacies on the Naloxone Standing Order List in New York City (42.3 %). It is possible for example that there was a systematic difference such that pharmacies that did not participate were less likely to carry naloxone.

- Relatedly, pharmacies that refused to be included did not provide any data for the study, thus precluding analysis of bias in non-response, and analysis of how pharmacies who refused to participate differ based on pharmacy or community-level characteristics.

- The data is self-reported, without the ability to verify if pharmacies carried naloxone in stock at the time of the call.

BOTTOM LINE

Findings from this study suggest that community-level socioeconomic marginalization is a marker for disparities in naloxone availability among pharmacies in New York City. This observation may also generalize to other major cities in the United States. This study highlights the need for multi-level research into interventions to widen access to naloxone in pharmacies in New York City and other urban areas. Such intervention strategies may include incentivizing enrolment in naloxone distribution plans or other insurance reimbursement programs, in addition to training pharmacists on the importance of overdose education. The study findings are also a call to action to scale up naloxone access in pharmacies in low-income neighborhoods that have been heavily impacted by the opioid epidemic in cities across the United States.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Naloxone is a life-saving medication with no misuse liability that can reverse the effect of an opioid overdose. It should be carried by all individuals using opioids and their family and friends. Encouraging local political representatives and community organizations to support naloxone availability initiatives could potentially increase naloxone availability and save lives in your community.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Naloxone is a life-saving medication with no misuse liability that can reverse the effect of an opioid overdose. It should be carried by all individuals using opioids and their family and friends, as well as treatment providers, and be stocked in clinics. Encouraging local political representatives and community organizations to support naloxone availability initiatives could potentially increase naloxone availability and save lives.

- For scientists: Naloxone is a life-saving medication with no misuse liability that can reverse the effect of an opioid overdose. More work is needed to disentangle the complex associations among socioeconomic factors and naloxone availability to reduce barriers to this medication. Scientists and public health experts may collaborate to develop, test, and disseminate innovative strategies to increase naloxone access for marginalized communities.

- For policy makers: Naloxone is a life-saving medication with no misuse liability that can reverse the effect of an opioid overdose. Government initiatives in many cities and states have helped increase the availability of this medication, and have reinforced the work of community organizations, who for a long time carried the weight of this task. At the same time, for many, accessing this medication is difficult, in large part because of restrictive laws regulating its distribution. Third-party prescribing laws (waiving the requirement that a provider and prescription recipient know one another), standing order laws (allowing a single provider to give a standing order for the medication that can be used by anyone who needs it), allowing pharmacies to directly prescribe naloxone, and medical amnesty/good Samaritan laws that protect individuals calling emergency services in the event of an overdose can all help reduce barriers to this medication and in turn save lives.

CITATIONS

Abbas, B., Marotta, P. L., Goddard-Eckrich, D., Huang, D., Schnaidt, J., El-Bassel, N., & Gilbert, L. (2021). Socio-ecological and pharmacy-level factors associated with naloxone stocking at standing-order naloxone pharmacies in New York City. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108388. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108388