How do individuals fare long-term after receiving long-acting, injectable formulations of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder?

Evidence has mounted regarding the short-term effectiveness of long-acting buprenorphine formulations for opioid use disorder, but knowledge about longer-term psychosocial and other health outcomes have been lacking. This paper reports 12-month outcomes from a study of individuals who had previously taken part in one of two, year-long, clinical trials of a long-acting, injectable formulation of buprenorphine for moderate to severe opioid use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

There is scientific consensus on the beneficial effects of the opioid use disorder medication buprenorphine, including decreased opioid use, decreased opioid-related overdose deaths, and possibly decreased criminal activity, decreased infectious disease transmission, and increased social functioning. Yet, little is known about longer-term patient recovery following pharmacologic treatment with this medication because most clinical trials to date haven’t followed participants past the first year.

Moreover, the longer-term benefits of long-acting, injectable formulations of buprenorphine, which have recently come onto the market, have not been particularly well studied, though emerging evidence suggests these formulations may increase uptake of these medications and decrease addiction related stigma, while improving addiction problem severity and quality of life.

The objectives of this study were to describe 12-month outcomes of individuals who had previously taken part in one of two, year-long, clinical trials of a long-acting, injectable formulation of buprenorphine, also known and marketed by the brand name Sublocade. Study outcomes have the potential to inform best practices for opioid use disorder treatment.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

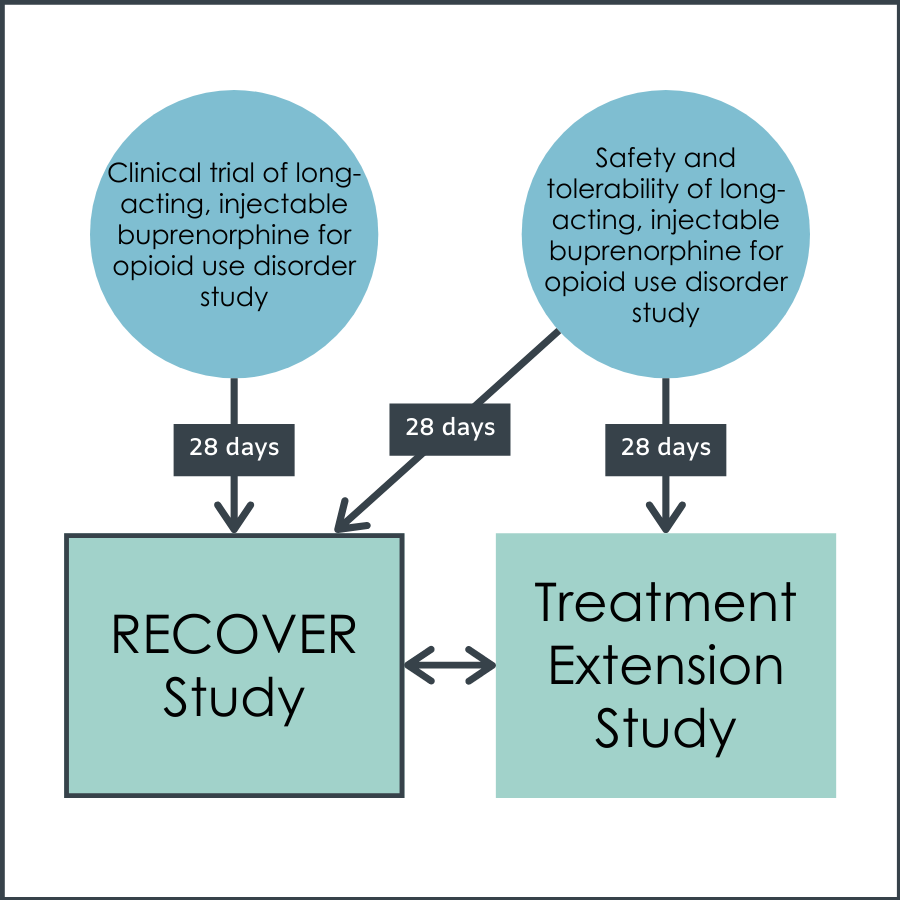

This was an observational investigation referred to as the RECOVER study (Remission from Chronic Opioid Use: Studying Environmental and SocioEconomic Factors on Recovery) that assessed opioid abstinence and other health outcomes over the course of a year in 533 patients with opioid use disorder who had previously received up to 12 monthly, long-acting buprenorphine injections as part of either a separate randomized clinical efficacy trial or a separate open-label safety study. Additionally, some RECOVER study participants also participated in a long-acting buprenorphine open-label extension study that ran concurrently with the RECOVER study, in which patients continued taking long-acting buprenorphine without being blinded to the medication they were receiving (i.e., active dose vs. placebo).

As part of the RECOVER study, participants completed detailed self-administered assessments concerning substance use, treatment for substance use disorder, and psychosocial measures at study enrollment, and at 6 and 12 months post-enrollment. Study enrollment occurred at least 28 days after completing or discontinuing participation in the long-acting buprenorphine clinical trials. A shorter battery of assessments was conducted at 3 and 9 months after enrollment. Urine drug tests were conducted at all visits. Participants were free to engage in any form of treatment while participating in the RECOVER study, and those who had continued to use long-acting buprenorphine after participating in the clinical trials were free to continue doing so.

Figure 1.

Study outcomes included, 1) self-reported sustained opioid abstinence over the entire 12-month reporting period, and 2) self-reported past week abstinence at each visit over 12 months. Additionally, individual outcomes collected at both the initial visit within the long-acting buprenorphine clinical trials, and within the RECOVER study were described. These included, 1) past month self-reported opioid abstinence, 2) opioid abstinence according to urine drug test results, 3) opioid withdrawal symptoms, 4) pain intensity, 5) quality of life, 6) depression severity, and 7) employment status.

RECOVER study participants were predominately male (66%), had a mean age at baseline of 42 years, and most had graduated from high school or had a general education diploma (67%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Of the 533 RECOVER study participants, 520 (98%) were eligible for survey completion (i.e., not deceased or incarcerated) at 3 months, 518 (97%) at 6 months, 508 (95%) at 9 months, and 506 (95%) at 12 months. For eligible participants, assessment completion rates were above 80% (82% at 3 months, 86% at 6 months, 81% at 9 months, 84% at 12 months), and drug testing completion rates were almost as high (78% at 3 months, 82% at 6 months, 79% at 9 months, 82% at 12 months). A total of 339 participants completed all visits (64% of the entire sample).

Many participants continued to take medication for opioid use disorder even after completing the clinical trial.

A total of 254 (48%) participants self-reported receiving treatment for a substance use disorder while participating in the RECOVER study. Many of these participants were receiving pharmacotherapy (39%), and nearly all who received pharmacotherapy (95%) were taking buprenorphine. Approximately three-quarters of those treated with buprenorphine were receiving long-acting buprenorphine through enrollment in the long-acting buprenorphine open-label extension study that ran concurrent with the RECOVER study. Counseling, reported by approximately 10% of study participants (Table 2), was the most commonly reported non-pharmacologic treatment modality, followed by mutual-help program participation (9%).

Among the 279 participants who did not receive any substance use disorder treatment (pharmacotherapy or other) during the entire 12-month RECOVER study follow-up period, 193 (69.2%) participants reported that they did not feel they needed further treatment.

Twelve-month opioid abstinence outcomes were promising.

When looking at quarterly abstinence within the full cohort, past-week, self-reported opioid abstinence was 63% at RECOVER study baseline, 74% at 3 months, 70% at 6 months, 68% at 9 months, and 66% at 12 months. Abstinence based on combined past-week self-report and drug testing ranged from 53% to 62% across visits. Concordance between drug testing and self-report was above 77% across all visits and showed that self-reports yielded consistently higher estimates of abstinence than drug tests.

Half (51%) of participants who completed the final 12-month RECOVER study visit had sustained abstinence over the entire 12-month observational period, based on no self-reported opioid use within the past 6 months reported at both the 6- and 12-month visits. However, when all self-reported evidence was used (i.e., no past-week, past month, or past 6-month self-reported days of use at quarterly visits), the sustained abstinence rate was 45%. When additionally requiring associated drug test results to be opioid negative, the sustained abstinence rate was 32%.

As may be expected, recalculating these statistics using “worst case imputation” in which missed follow-up sessions were coded as presumed positives for opioid use, showed lower abstinence rates, ranging from 63% at baseline, to 53% at 12 months when participants were assumed to be non-abstinent at all missing visits.

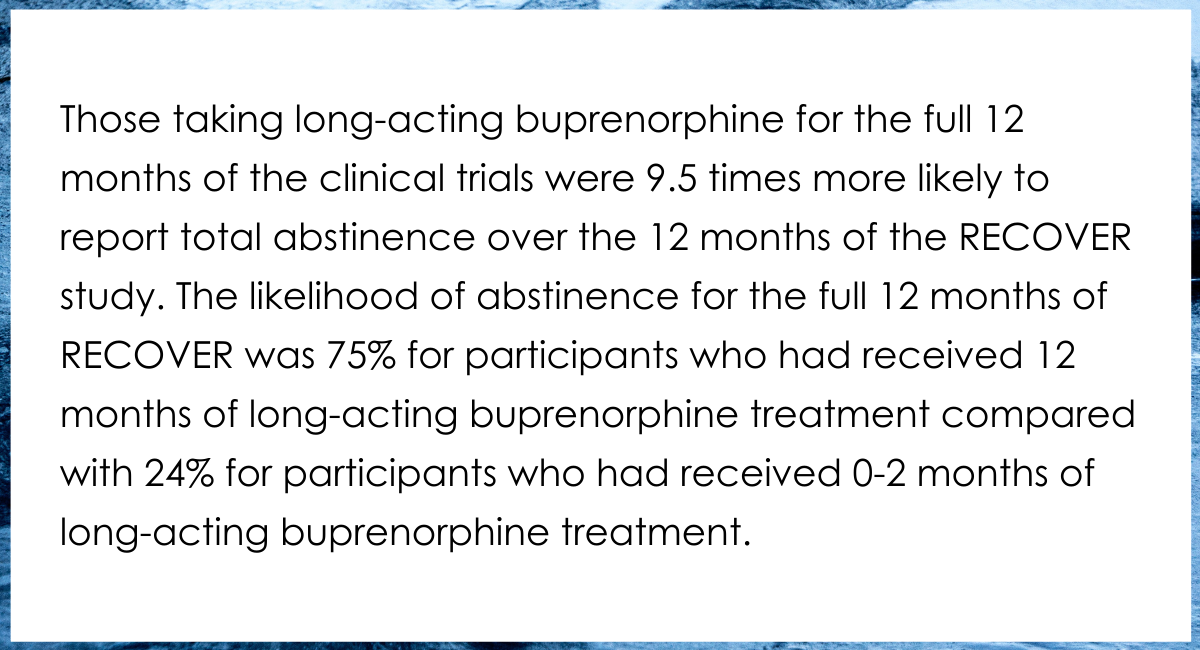

12-month abstinence rates also looked promising, particularly among those who took buprenorphine for longer during the initial clinical trial.

Those taking long-acting buprenorphine for 6-11 months during participation in the clinical trials were almost twice as likely than those who only received 0-2 months of long-acting buprenorphine treatment to report total abstinence over the 12 months of the RECOVER study. Further, those taking long-acting buprenorphine for the full 12 months of the clinical trials were 9.5 times more likely to report total abstinence over the 12 months of the RECOVER study. The likelihood of abstinence for the full 12 months of RECOVER was 75% for participants who had received 12 months of long-acting buprenorphine treatment compared with 24% for participants who had received 0-2 months of long-acting buprenorphine treatment.

Figure 2.

Improvements were also observed in other health outcomes.

Withdrawal symptoms and pain scores, on average, were both lower during RECOVER study as compared to visits immediately before starting the clinical trials. Additionally, the proportion of participants reporting no to minimal depression (vs. more severe depression) increased from 30% at the randomized efficacy or open-label safety trial screening visit to over 70% at RECOVER baseline and 12-month visits. Employment rates during the first 12 months of RECOVER also doubled from those measured at the randomized efficacy or open-label safety trial screening visit.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The researchers found that RECOVER participants endorsed either improved or maintained low levels of withdrawal symptoms, low pain levels, improved or maintained positive health related quality of life, low levels of depression, and higher employment rates as compared to those entering the clinical trials for long-acting, injectable buprenorphine that preceded this study. Additionally, participants who took the long-acting buprenorphine injections for longer had better opioid use outcomes. These are promising findings which speak to potential sustained benefit from this class of medication. However, given that by design the RECOVER cohort only included previous participants of the long-acting buprenorphine trials, the generalizability of these results to individuals outside of a clinical trial treatment setting is limited. It is well appreciated that individuals participating in treatment studies often experience better outcomes than individuals receiving the same treatment/medications in real-world settings because the ongoing monitoring of clinical research may unintentionally enhance clinical outcomes over and above the effects of the actual treatment they receive. Thus, it can’t be known how these findings would generalize to individuals with opioid use disorder who are receiving long-acting buprenorphine through usual channels in the community like outpatient addiction treatment clinics. It’s also very important to note that observational studies such as this often include some unavoidable self-selection biases (e.g., recovery motivation).

Notably, older individuals and those who had taken buprenorphine prior to participating in the initial clinical trial had lower abstinence rates over the 12-month RECOVER study period. This may be a marker of greater addiction problem severity, and should not be interpreted as meaning that having a history of taking buprenorphine is responsible for lower abstinence rates.

Findings were also notable in that very few participants in the RECOVER study were engaged in counseling (10%) or mutual-help programs like Narcotics Anonymous (9%) through the course of this 12-month study. This is perhaps unusual given counseling and mutual-help program participation are commonly recommended and practiced by individuals taking opioid use disorder medications. It’s possible this reflects the study’s sample characteristics. The RECOVER study (and the clinical trials preceding it) may have attracted individuals more motivated to utilize a medication for opioid use disorder that requires minimal time investment (i.e., monthly injections) versus taking a daily medication or engaging with therapy or mutual-help. Though such individuals of course exist in the spectrum of individuals seeking help for opioid use disorder, this may also mean that the authors’ findings don’t generalize well to other types of individuals seeking help for opioid use disorder. An interesting hypothesis that could be tested in future research is that that daily buprenorphine dosing is associated more with a recovery/growth orientation versus long term injections.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the authors:

- It is likely that some participants lost to follow-up had relapsed to opioid use disorder. Though the authors showed abstinence outcome findings that assumed the worst case scenario in which all missed sessions were presumed positives for opioid use, a similar correction was not provided for patient centered outcomes like pain and depression.

- During participation in the long-acting buprenorphine clinical trials prior to the RECOVER study, duration of long-acting buprenorphine treatment was based on participants’ voluntary continuation in the clinical trial and participants were not randomized to treatment duration groups. Therefore, it is possible that there might be characteristics related to duration of medication treatment (e.g., recovery motivation) that might have an impact on abstinence and other outcomes in the RECOVER study.

- Differences in abstinence across long-acting buprenorphine duration groups may also be attributable to opioid use disorder pharmacotherapy that occurred during the RECOVER follow-up period.

- Fentanyl (a commonly used synthetic opioid) was drug tested but was not explicitly asked about within patient surveys.

- Generalizability of these results may be limited because all RECOVER participants had previously participated within a long-acting buprenorphine trial.

- Because many participants in the study continued to receive long-acting buprenorphine through an extension study of one of the clinical trials, continuation of long-acting buprenorphine use in this study does not reflect natural uptake of this medication. It is possible many participants would have discontinued use of long-acting buprenorphine after the clinical trial, were they not participating in the extension study.

- Though not necessarily a limitation, but nevertheless important to note, all the authors of this paper worked for a company that produces the medication being tested in this research. While there was no evidence of experimentor bias in this paper, it is important to note that a conflict of interest exists whenever researchers publish findings on interventions they are directly or indirectly financially involved with.

BOTTOM LINE

Findings from this study and previous clinical trials of long-acting, injectable formulations of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder have shown this medication can decrease opioid use and opioid-related overdose deaths. This study found that greater utilization of this medication was associated with less opioid use and higher probability of opioid abstinence, improved or maintained low levels of opioid withdrawal symptoms, low pain levels, improved or maintained positive health related quality of life outcomes, minimal depression, and higher employment rates as compared to the values observed prior to entering the clinical trials for long-acting, injectable buprenorphine that preceded this study. At the same time, these findings should be taken in context. Because of the way this study was structured, it can’t be known what portion of these positive outcomes were driven by medication effects, versus participants’ intrinsic motivation, or other factors. This however does not diminish the growing evidence base highlighting benefits of long-acting, injectable formulations of buprenorphine. This class of medications can help support opioid use disorder recovery as a stand-alone treatment, but may be most effective when used in combination with psychological treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and/or mutual-help groups like Narcotics Anonymous or SMART Recovery.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: There is growing evidence highlighting benefits of long-acting, injectable formulations of buprenorphine. This class of medications can help support opioid use disorder recovery as a stand-alone treatment, but may be most effective when used in combination with psychological treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and/or mutual-help groups like Narcotics Anonymous or SMART Recovery.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: There is growing evidence highlighting benefits of long-acting, injectable formulations of buprenorphine. This class of medications should be considered to support patients seeking opioid use disorder recovery. While evidence suggests buprenorphine is effective as a stand-alone treatment, it may be most effective when used in combination with psychological treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and/or mutual-help groups like Narcotics Anonymous or SMART Recovery.

- For scientists: Randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are needed to remove selection bias effects and estimate the true medication-attributable benefits.

- For policy makers: Results generally support the growing evidence base highlighting benefits of long-acting, injectable formulations of buprenorphine. Increasing access to these medications should be a top public health priority. One way to achieve greater access to these medications is by creating/modifying legislation that makes it easier to pay for and prescribe these medications.

CITATIONS

Ling, W., Nadipelli, V. R., Aldrige, A. P., Ronquest, N. A., Solem, C. T., Chilcoat, H., . . . Heidbreder, C. (2020). Recovery from opioid use disorder after monthly long-acting buprenorphine treatment: 12-month longitudinal outcome from RECOVER, an observational study. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 14(5), e233-e240. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000647