Long-Term Treatment Outcomes for Individuals with Opioid Use Disorders

Despite the existence of effective treatment options, the opioid epidemic continues to grow in the U.S.

Rates of opioid use disorder vary by primary substance used with an estimated 1.8 million people having a prescription opioid use disorder compared to 517,000 with heroin use disorder.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Despite, more individuals misusing prescription opioids than heroin, previous longitudinal studies of opioid users tend to focus on people who use heroin. Additionally very little is known about long-term outcomes among opioid use disorder patients receiving medications (see a previous recoveryanswers.org summary here). Since people misusing prescription opioids may experience outcomes differently than those who use heroin, this study with 42 months (i.e., 3.5 years) of follow-up focuses solely on the outcomes of patients with prescription opioid use disorder participating in the Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study (POATS).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This is a follow-up study of participants from Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study (POATS), a multi-site randomized controlled trial consisting of a brief treatment phase (2 weeks of buprenorphine-naloxone, followed by a 2 week taper off of the medication, and 8 weeks of follow-up) and an extended treatment phase (12 weeks of buprenorphine-naloxone stabilization, followed by a 4 week taper off of the medication, and then 8 weeks of follow-up) which was offered to those who did not achieve abstinence or near-abstinence in the first phase (see here for the original POATS paper).

Participants meeting DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence due to prescription opioids who were not on opioid agonist therapy (OAT; i.e., not currently receiving medications such as methadone or buprenorphine-naloxone) upon treatment entry were eligible unless they had used heroin over 4 times in the past 30 days, had a lifetime opioid dependence diagnosis due to heroin alone, had ever injected heroin, or required opioid for pain management. Participants were randomized to receive weekly Standard Medical Management (SMM) consisting of medically-oriented counseling during the visit with the physician to adjust dosing or SMM and Opioid Dependence Counseling (ODC) which focused on development of relapse prevention skills. Results of the initial trial showed better rates of success after the extended treatment phase than after the initial phase (49% vs. 7%) with no difference between counseling conditions.

Rates of success from the extended treatment phase were not maintained 8 weeks after the buprenoprhine-naloxone taper (see here). Of 653 individuals participating in POATS, 375 (57%) were enrolled in the follow-up study which consisted of telephone interviews at 18, 30, and 42 months after the participant first entered POATS.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Prior to treatment, all participants met criteria for opioid dependence and were not on opioid agonist therapy (OAT).

NOTABLY FROM THE STUDY:

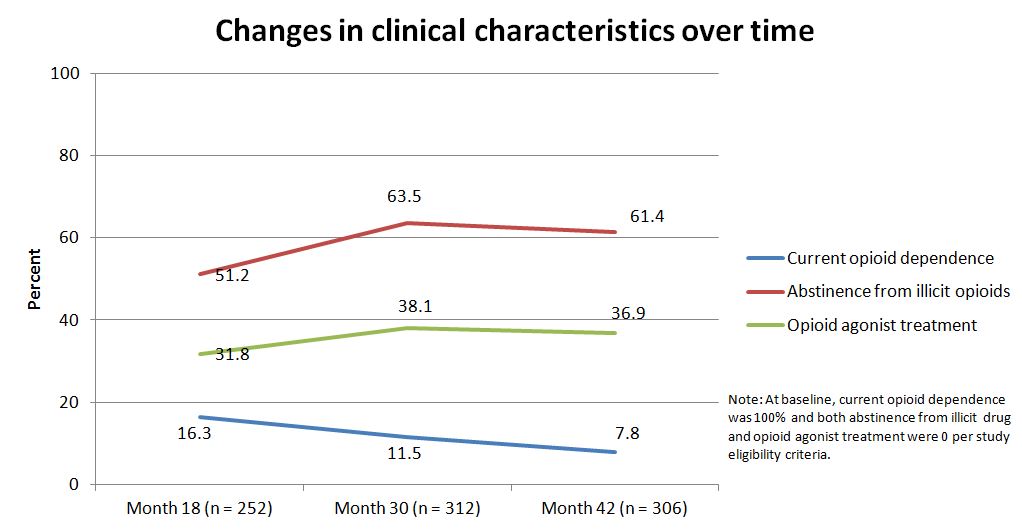

- Regarding improvements in clinical characteristics, the proportion of participants with current opioid dependence decreased over time while the proportion abstinent from illicit opioids increased over time

- About half were abstinent at 18 months, and this increased significantly at 30 months

- OAT use, which was zero at the start of the study, increased at 18 months and then remained steady. These changes are highlighted in the graph below

At study entry, 266 participants reported never having used heroin. By the 30 month assessment, 10% of these participants reported heroin use. Using heroin greater than 4 days in the past month was an exclusion criterion for the Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study (POATS). Despite initially reporting heroin use below this level at study entry, by month 42, over 41% of those using heroin reported use at this level. On the other hand, two thirds of participants who reported lifetime heroin use at baseline were no longer using heroin during follow-up.

Regarding substance use disorder (SUD) treatment after the treatment period, about two thirds of participants remained in treatment with buprenorphine maintenance as the most common form. Treatment use that declined over time included mutual-help group attendance and outpatient counseling.

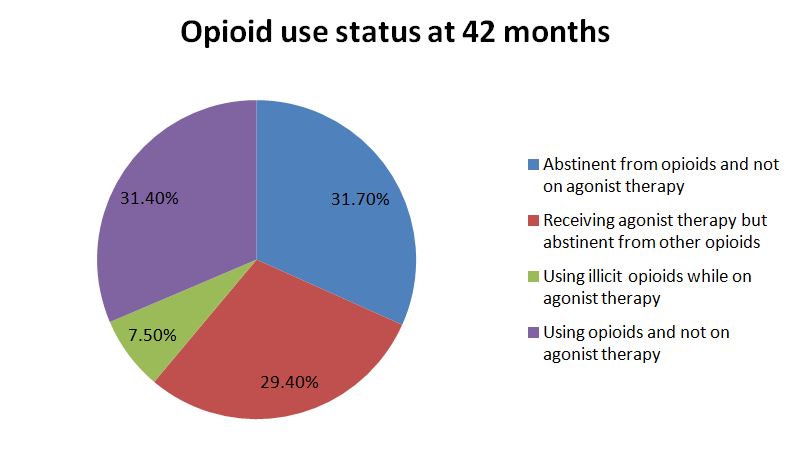

Consistent with results from the main treatment trial, engagement in agonist therapy was significantly associated with abstinence by the end of follow-up at 42 months with 80% of participants on opioid agonist therapy (OAT) reporting abstinence from other opioids in the past month compared to half of those not on OAT.

Successful outcomes from the initial trial were not found to be predictors of abstinence at 42 month follow-up. For those who may not respond to treatment initially, this does not mean that they won’t achieve remission at a later point in time.

This long period of follow-up supports the effectiveness of buprenorphine-naloxone treatment in the Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study (POATS) as patients showed improvements in opioid outcomes over the 3.5 years since study enrollment. In addition to substance use outcomes, patients experienced improvements in general health and pain.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Medications (e.g. buprenorphine-naloxone) can:

- decrease cravings and relieve withdrawal

- decrease post-acute withdrawal symptoms affording some patients the opportunity to remain in and focus on treatment

- allow individuals to return to the workforce

- reduced rates of relapse

- reduced likelihood of blood-borne infections like HIV and hepatitis C

By following participants for 42 months after the start of this study, more information is available about the long-term outcomes of buprenorphine-naloxone treatment such as a possible waning of improvements observed during and shortly after the treatment period. The study’s research questions are consistent with a recovery management model, such that an ongoing, continuous approach to care — rather than single and separate treatment episodes — may be needed to help people initiate and sustain recovery and remission.

When comparing this study to long-term follow-up studies of heroin users (see here) patients with prescription opioid use disorder may fare better overtime. While results were mainly positive, a small proportion of participants initiated heroin use during follow-up which mimics the transition from prescription opioid to heroin use seen in other studies (see here) and often portrayed in the media. Such patients may need more intensive treatment over time to prevent relapse to prescription opioid use or the initiation of heroin use.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Since about half of POATS participants did not enter the follow-up study, a selection bias may be present such that participants who were more successful with treatment may be more likely to participate.

- It was also difficult for study staff to re-enage patients as a majority had completed the main trial over a year before being contacted about the follow-up study.

- Another limitation is that follow-up interviews were conducted over the phone and relied on self-report from participants which may have resulted in higher rates of favorable outcomes.

NEXT STEPS

For a chronic. illness long-term follow-up is important for determining if a treatment is effective at helping patients achieve remission. Future studies should plan for a long follow-up period prior to enrollment so study staff can continually engage with participants throughout the course of the study since lack of contact with participants may result in greater loss to follow-up. When possible, in-person evaluations would allow researchers to collect urine samples to increase confidence in the verbally-reported results.

More research with long-term follow-up is needed to determine the influence of medications on abstinence and remission among heroin users and sub-groups that are challenging to engage in care (e.g., emerging adults). It is also important to determine how many “episodes” of care using medications and/or other treatment are needed for patients to achieve successful outcomes.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Recovery is a lengthy process. In this study, over half of participants were abstinent from all opioids or on opioid agonist therapy (OAT) at 3.5 years after study initiation. As seen in the current study, successful outcomes from the initial trial did not predict abstinence at 42 months. This suggests that lack of initial treatment response does not mean you will not achieve remission later on.

- For scientists: This study is an important preliminary step regarding longer term efficacy of buprenorphine-naloxone in aiding recovery from SUD, but more research with planned longer term follow-up is needed to capture all people who entered the study. Future treatment studies adding a follow-up component can compare long-term outcomes to end of treatment or short-term outcomes.

- For policy makers: To inform long-term recovery management strategies, consider allocating funds to research that aims to follow treated individuals for multiple years after the index episode.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study supports buprenorphine-naloxone as an effective treatment for patients with prescription opioid use disorder. Discussing these treatment options with substance use disorder (SUD) patients, and prescribing or making referrals to prescribers, is likely to enhance the chances of long-term recovery for those suffering from opioid use disorders.

CITATIONS

Weiss, R. D., Potter, J. S., Griffin, M. L., Provost, S. E., Fitzmaurice, G. M., McDermott, K. A., . . . Carroll, K. M. (2015). Long-term outcomes from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study. Drug Alcohol Depend, 150, 112-119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.030