Does it matter where you get medication for opioid use disorder? A comparison of three types of clinics

Individuals receiving buprenorphine for opioid use disorder may or may not receive additional treatment, such as individual and group therapy, family services, and referral to mutual-help groups. This may depend in large part upon the philosophy and resources of the clinic in which buprenorphine is prescribed. Do substance-related outcomes vary across different types of community clinics?

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

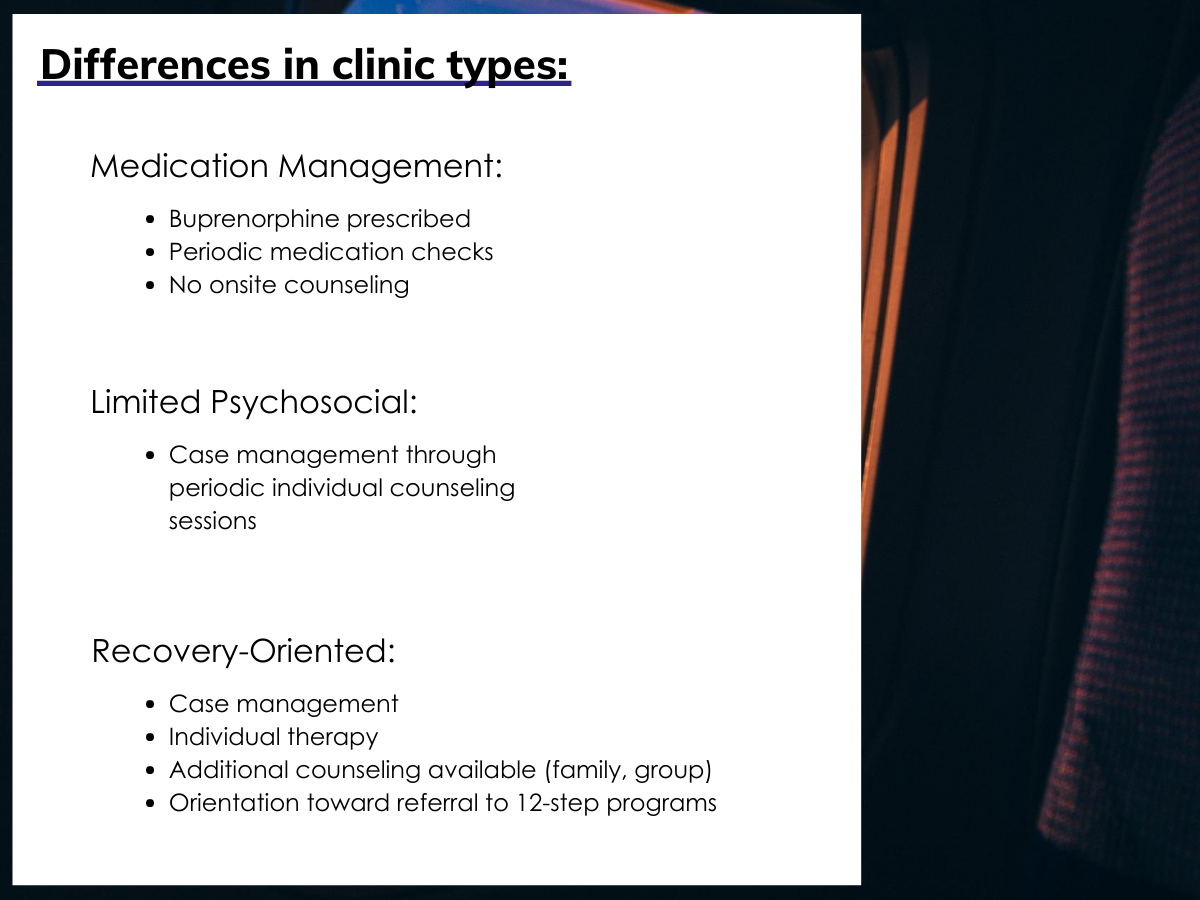

Buprenorphine (often prescribed in combination with naloxone, known by the brand name Naloxone) is a medication for opioid use disorders that can be prescribed in a variety of clinical settings, ranging from doctors’ offices to specialty substance use disorder treatment, as well as opioid treatment programs. Many federal organizations, such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), recommended that individuals receiving buprenorphine receive other behavioral health services (for example, individual or group psychotherapy) in addition to standard medication management, though this does not always happen in practice. Some critics of this recommendation for additional psychosocial services suggest that requiring such services in order to receive buprenorphine introduces barriers to receiving this empirically supported medicine. Research regarding the added benefit of psychosocial treatment to buprenorphine is mixed, with studies generally showing individual therapy is helpful in cases where standard psychosocial monitoring and support added to the medication – referred to as “medication management” – is less intensive. However, mutual-help group attendance in organizations such as Narcotics Anonymous, has been consistently associated with better outcomes for those taking buprenorphine. In this study, Galanter and colleagues used a large dataset from a national toxicology laboratory to understand more about the differences in opioid use outcomes across different types of clinics that prescribe buprenorphine. They examined three types of clinics: those offering medication management only, those with limited psychosocial services, and those offering multiple types of psychotherapy and referrals to mutual-help groups.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study compared urine drug test results for the presence of opioids, apart from buprenorphine, in individuals who received at least two buprenorphine prescriptions in three types of treatment facilities: medication management only (n = 138 clinics and 6103 patients); limited psychosocial therapy (n = 9 clinics and 2557 patients); and recovery-oriented (n = 109 clinics and 11,589 patients).

Figure 1.

The study used anonymous data from a large toxicology laboratory database and included data from 20,993 individuals in 573 clinics in 41 states across the United States. Information on specific program locations was not reported. From this dataset, individuals were included in the study if they were prescribed buprenorphine at the clinic at least twice within a 2.5-year study period (n = 13,281). These individuals were selected because they were considered to have experienced an “episode” of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. The time between the first and second buprenorphine prescriptions was classified as the “buprenorphine episode,” which was 1.5 months, on average.

The primary outcome of interest was whether the individual had a urine drug test result that was negative for other opioids at the time of the second buprenorphine prescription. It is important to note that other opioids could include both opioids that were prescribed by another provider and taken as prescribed, non-medical use of opioids prescribed by another provider, and opioids that were obtained illicitly.

The authors completed two sets of analyses. The first was a comparison of urine drug test results at the time of the second buprenorphine prescription across the three types of clinics: medication management only, limited psychosocial therapy, and recovery-oriented. The second was a comparison of urine drug test results for new versus established patients across the three types of clinics. A patient was considered new if they did not have previous drug tests in the clinic before their buprenorphine episode (i.e., before receiving their first buprenorphine prescription). A patient was considered established if they had at least one prior drug test in the clinic before their buprenorphine episode.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

There was no difference across clinic types in the percentage of patients who received a second buprenorphine prescription.

At medication management clinics, 68% of patients received a second prescription during the study period, compared with 67% of patients at limited psychosocial clinics and 65% of individuals at recovery-oriented clinics. This indicates that the three types of clinics were equally successful at retaining patients in buprenorphine treatment, but that a substantial proportion of patients nationwide (32-35%) did not receive ongoing buprenorphine treatment at a single clinic during the 2.5-year study period.

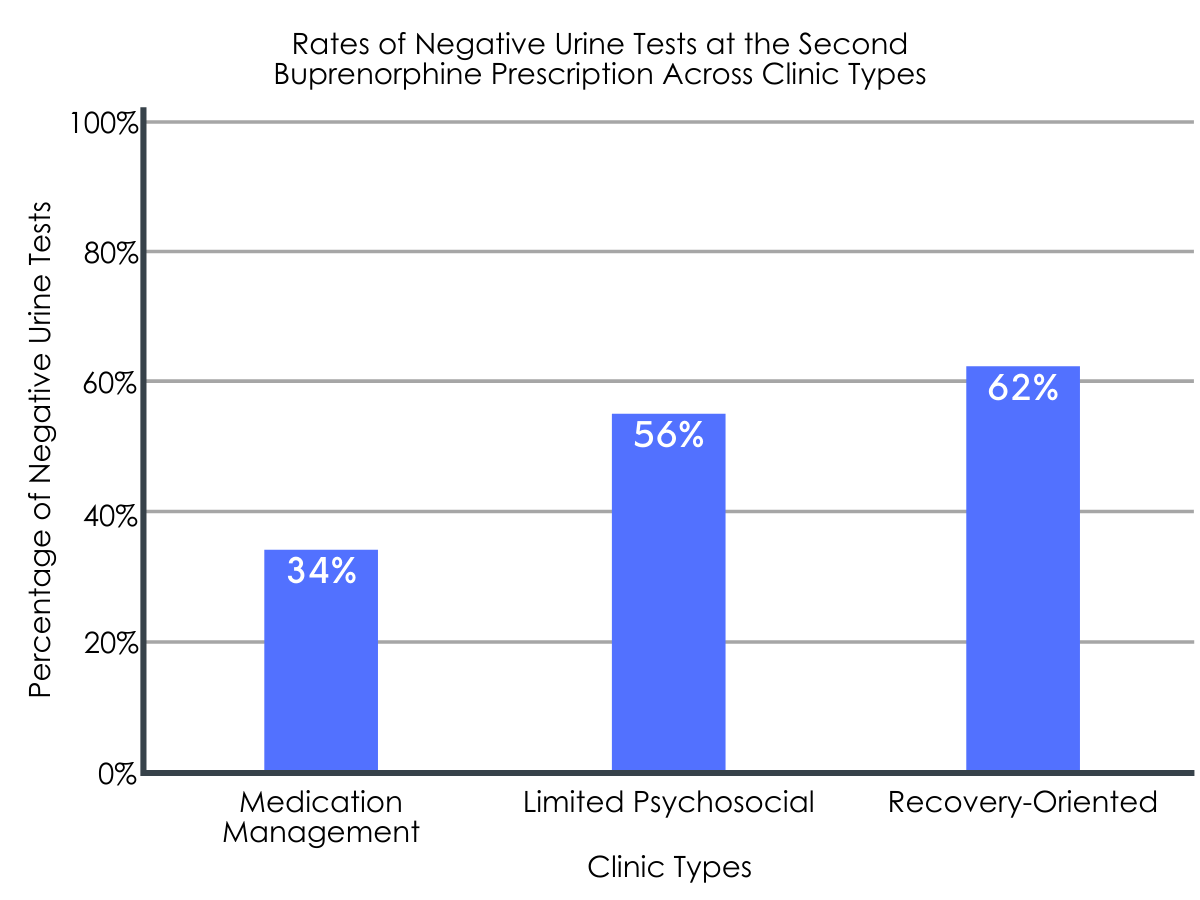

Recovery-oriented clinics had better outcomes than those with medication management only.

Recovery-oriented clinics, which had the most intensive services available to patients, had the highest rate of opioid-negative urine tests (62%) at the time of the second buprenorphine prescription, which was greater than clinics with medication management only (34%).

Figure 2.

The difference in outcomes between new and established patients was greatest for recovery-oriented clinics.

Urine test results were examined for new versus established patients prior to their first buprenorphine prescription during the study period. The difference in the likelihood of having an opioid-negative urine test varied across the three types of clinics. This difference was highest for patients in recovery-oriented clinics (17% difference favoring established patients), compared to limited psychosocial (5% difference favoring established patients) and medication management (13% difference favoring established patients).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The results of this study suggest that there are differences in outcomes across different types of clinics that prescribe buprenorphine, with the clinics with the most available treatment resources having better outcomes than clinics with the least resources. Additionally, the benefit of remaining a patient in the clinic appears to be greatest for recovery-oriented clinics. That is, in these recovery-oriented programs, the likelihood of have an opioid-negative toxicology screen increases over time, suggesting increased benefit only for those who remain engaged, while this is not the case for programs offering medication management only or limited psychosocial treatment. However, because this was an observational study, this study cannot tell us the cause of these outcomes. While it may be that programs offering therapy and mutual-help facilitation services improve patient outcomes compared to programs that do not offer these services, it is also possible that better resourced clinics attract patients with more resources, or patients who are more motivated to take part in additional treatment resources, including individual, group, and family psychotherapy.

This study adds to dozens of studies that have examined the benefit of adding psychosocial counseling services to medications for opioid use disorders. Some studies have shown no added benefit of psychosocial interventions in terms of opioid use and related outcomes, with individuals receiving medication management alone reducing their opioid use just as much as individuals receiving medication management and additional psychotherapies. In contrast, other studies have found an improvement in substance use outcomes when individuals are treated with medication plus psychosocial interventions, in contrast to medications alone. One possible explanation is that psychosocial treatments do not produce an added benefit when medication management services are already fairly intensive. In clinical trials that found no added benefit of psychotherapy, participants in the medication management only condition were already receiving weekly sessions, which may raise the threshold for additional interventions to produce an effect. Most of the clinical trials that showed an added benefit of psychotherapy did not describe having structured medication management. Since the researchers in this study did not describe the intensity of services at the medication management only clinics compared to limited psychosocial and recovery-oriented clinics, we cannot determine whether the intensity of services was related to the observed outcomes.

It is important to note that medication management, even in the absence of additional therapy, generally includes recommendations to attend non-professional, community-based mutual-help groups. The recovery-oriented clinics in this study also included an orientation toward referring clients to mutual-help fellowships, such as Narcotics Anonymous. Prior research has shown that among individuals who receive buprenorphine for opioid use disorder, participation in mutual-help groups is associated with a 2-3 times greater likelihood of abstinence over a 3.5-year period, compared to individuals who do not attend mutual-help groups. It is possible, although not specified in the current study, that attendance at mutual-help groups can help explain why recovery-oriented clinics had better outcomes than the other clinic types.

At all types of clinics, a substantial proportion of clients (32-35%) did not return to the clinic for a second buprenorphine prescription during the 2.5-year study period. This is consistent with other research showing high rates of dropout from medication treatment for opioid use disorders. Dropout from opioid use disorder medication treatment is especially problematic since it increases risk for death, including but not limited to overdose death. Because the study only included individuals who returned to the clinic for a second buprenorphine prescription, it is not possible to determine if individuals who dropped out received ongoing buprenorphine treatment elsewhere.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- No information was provided on patient characteristics across the three clinic types (for example, socio-economic factors, clinical complexity, severity of opioid use disorder) and whether patient characteristics differed systematically across the three types of clinic. Thus, we cannot determine the extent to which existing differences among patients treated in the three types of clinical settings may have contributed to the differences in the clinical findings.

- No information was given on what services patients were involved in at each clinic, or whether certain types of clinics required patients to engage in particular treatment activities in order to get or maintain a buprenorphine prescription. It is not possible to determine whether patient engagement in additional treatment services contributed to the findings.

- It was unclear whether the first buprenorphine prescription during the study period (beginning January 2015), which marked the start of the “buprenorphine episode,” represented an individual’s first buprenorphine prescription within the clinic, or whether they may have received prior buprenorphine in the clinic prior to the start of the study period. If individuals attending recovery-oriented treatment programs were engaged for longer periods of time compared to the other two programs, it may be that longer time in treatment generally, rather than the program itself, accounted for the higher proportion of opioid negative drug tests in the recovery oriented treatment group.

- No information was provided on the length of buprenorphine prescriptions, and whether individuals returning for a second prescription experienced a lapse in their buprenorphine prescription from the first time point to the second. Because of this, it is unclear whether the use of other opioids at the second time point represented replacement use or concurrent use. If this varied systematically across clinic types, it may represent a possible explanation for the findings.

- No information was given on the types of buprenorphine used (for example, implant vs. oral; with or without naloxone) and whether this varied across clinic types.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study compared opioid use during an episode of buprenorphine treatment, as measured by urine drug tests, across three types of clinics. Findings suggest that treatment systems that offer multiple formats of psychotherapy (individual, group, family) and refer individuals to mutual-help organizations demonstrate lower rates of secondary opioid use than clinics that offer medication management only. While this study does not provide information on cause and effect, individuals and families may be better off seeking buprenorphine treatment in well-resourced clinics that systematically refer and encourage patients to attend mutual-help groups, compared to clinics that provides monitoring and less intensive referrals to mutual-help. However, other research shows that if medication management is provided at a high enough intensity (specifically, weekly sessions), it may be sufficient to improve outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study compared opioid use during an episode of buprenorphine treatment, as measured by urine drug tests, across three types of clinics. Findings suggest that treatment systems for individuals receiving buprenorphine that offer multiple formats of psychotherapy (individual, group, family) and refer individuals to mutual-help groups demonstrate lower rates of secondary opioid use than clinics that offer medication management only. As dropout from buprenorphine treatment remains a problem for at least one-third of clients, treatment professionals and systems should continue to look for ways to keep individuals engaged in treatment.

- For scientists: This study compared opioid use during an episode of buprenorphine treatment, as measured by urine drug tests, across three types of clinics. Findings suggest that treatment systems for individuals receiving buprenorphine that offer multiple formats of psychotherapy (individual, group, family) and refer individuals to mutual-help groups demonstrate lower rates of secondary opioid use than clinics that offer medication management only. Because this was an observational study, it is not possible to identify why recovery-oriented clinics showed better outcomes than medication management only clinics, or why the discrepancy in outcomes between established and new patients was greatest for recovery-oriented clinics. Future research using naturalistic, observational study designs should control for important covariates that can also explain outcomes, such as patients’ recovery capital, motivation, and engagement in psychosocial services, as well as the intensity of medication management services (see Limitations section). Ultimately, randomized trials and/or rigorous quasi-experimental work is needed to determine the real-world benefits of adding mutual-help group facilitation to buprenorphine.

- For policy makers: This study compared opioid use during an episode of buprenorphine treatment, as measured by urine drug tests, across three types of clinics. Findings suggest that buprenorphine clinics that offer multiple formats of psychotherapy (individual, group, family) and refer individuals to mutual-help groups show greater reductions in opioid use than clinics that offer medication management only. However, because this was an observational study that did not control for important covariates, developing healthcare policies based on the findings would be premature. This study’s limitations, and the mixed findings of other studies on the added benefit of psychotherapy during opioid medication treatment, underscore the importance of not mandating that individuals receive psychotherapy in order to receive medication for opioid use disorder. They also highlight the potential yield of funding high quality studies to examine the real-world effects of adding interventions that systematically link and encourage patients taking buprenorphine to attend mutual-help groups.

CITATIONS

Galanter, M., Femino, J., Hunter, B., & Hauser, M. (2020). Buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder in community‐based settings: Outcome related to intensity of services and urine drug test results. American Journal on Addictions, 29, 271-278. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13001